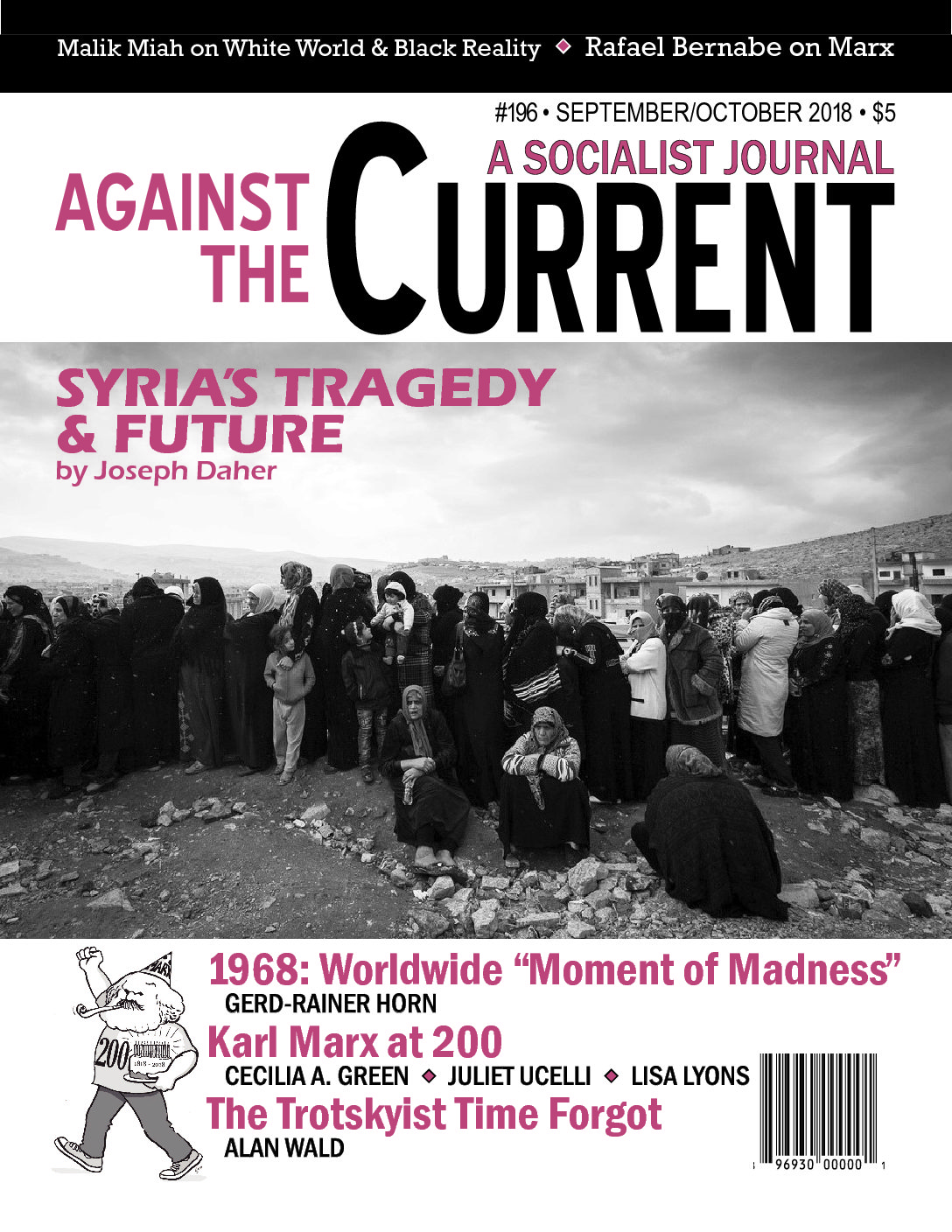

Against the Current, No. 196, September/October 2018

-

Where to Begin?

— The Editors -

The White World and Black Reality

— Malik Miah - Who Killed Marielle?

-

Worldwide "Moment of Madness"

— Gerd-Rainer Horn -

European Communist Parties and '68

— Gerd-Rainer Horn - Fascist Attack in Chile

- UPS Update

- Update on Syria

-

Syria's Disaster, and What's Next

— Joseph Daher - Karl Marx at 200

-

Janus and My Ode to Capital

— Juliet Ucelli -

Historical Subjects Lost and Found

— Cecilia A. Green - Review Essay

-

Marx Turns 200: A Mixed Gift

— Rafael Bernabe - Marx's Capital

-

On the "Transformation Problem"

— Barry Finger -

Reply

— Fred Moseley -

Marx, Engels and the National Question

— Peter Solenberger - Revolutionary History

-

Nicolas Calas: The Trotskyist Time Forgot

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Struggling for Justice

— Cheryl Higashida -

The Power of Story, the Evidence of Experience

— Sarah D. Wald -

An Unrepentant '68er's Life

— K. Mann - In Memoriam

-

Martha (Marty) Quinn, 1939-2018

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Joel Kovel (1936-2018)

— DeeDee Halleck and Michael Steven Smith

Cheryl Higashida

Louise Thompson Patterson:

A Life of Struggle for Justice

By Keith Gilyard

Durham: Duke University Press, 2017, 282 pages + index, $26.95 paperback.

I FIRST STUMBLED upon Louise Thompson Patterson as a Ph.D. student in the 1990s researching Richard Wright. I had been astonished to learn that canonical African-American writers and artists had been involved with the international Left — and that anti-Communism and racism had effectively erased this history.

After encountering Thompson Patterson in William Maxwell’s New Negro, Old Left: African-American Writing and Communism Between the Wars (1999), I was further amazed by the rich, suppressed history of Black women’s radicalism predating the “golden age” of the civil rights movement.

Opening his brief yet insightful discussion of Thompson Patterson’s 1930s activism, Maxwell wrote, “Even with the ongoing boom in scholarship on African-American women intellectuals, Louise Thompson is lamentably still recognized best for two temporary jobs as an artistic helpmeet.” (141)

This should no longer be the case, with the publication of Keith Gilyard’s Louise Thompson Patterson: A Life of Struggle for Justice, the first book-length biography of this remarkable organizer, educator, cultural worker and Black Left feminist.

Taking advantage of the fact that Thompson Patterson’s life literally spanned the 20th century from 1901 to 1999, Gilyard explores Thompson Patterson’s involvement in momentous events. These include the 1927 Mississippi River flood (“that era’s Hurricane Katrina” [47]); the 1927 Hampton student strike; the Harlem Renaissance; the anti-lynching Scottsboro campaign; the Spanish Civil War; the Popular Front; the Chicago Renaissance; the founding of the National Negro Congress, the Civil Rights Congress, and the Council on African Affairs; African-American solidarity with the Soviet Union, Cuba and the People’s Republic of China; the Black Power movement; and, at age 69, the campaign to free Angela Davis.

In so doing Gilyard shows how Thompson Patterson’s career, and that of other Black women activists, impacted and reinterpreted the meanings and outcomes of African-American, workers’ and women’s struggles.

New Scholarly Tradition

Gilyard’s book is in the tradition of scholarship on African-American radicalism and Black Left feminism that has flourished over the past 20 years. These range from Barbara Ransby’s biographical studies of Ella Baker and Eslanda Goode Robeson, Gerald Horne’s of Shirley Graham Du Bois and William Patterson, Gregg Andrews’ of Thyra Edwards, to Carole Boyce Davies’ of Claudia Jones. Additionally there is the body of research on African-American women on the Left by Mary Helen Washington, Erik McDuffie, Dayo Gore, Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard.

Gilyard draws on Thompson Patterson’s unfinished memoir and other unpublished and published writings, “several hundred hours of audiotapes and videos” from the Louise Thompson Patterson Memoirs Project of the African American Studies Department at U.C. Berkeley, FBI records, and his own interviews. Gilyard synthesizes this massive research into a well-organized, highly readable narrative.

Thompson Patterson’s childhood and early adulthood, likely the least known parts of her life story, are utterly fascinating. Gilyard asserts that her family’s constant movement across the Midwest and West, and her liminality as a light-skinned African American who could and did pass for white (a “choice” importantly qualified by the depth of anti-Black racism), fostered a desire for community in Thompson Patterson that would lead her to become a great teacher and organizer.

Meanwhile, the example of her mother Lulu (Louise) Brown Toles and other strong Black women, along with her experiences with racism and patriarchy, led to what Black feminists would later call an “intersectional” analysis of the “triple oppression” of Black women that demonstrated the centrality of racial justice and women’s rights to class-based struggles.

Gilyard further explores Thompson Patterson’s years at U.C. Berkeley — where she co-founded the first historically Black sorority west of the Mississippi River and became one of Berkeley’s few early African-American graduates — and her subsequent period teaching at two historically Black colleges, Pine Bluff in Arkansas and the Hampton Institute in Virginia. These experiences spurred Thompson Patterson’s lifelong commitment to education, for which she would be honored later in life.

The biography continues to provide fresh insights into U.S., Black, Left and literary histories as it moves to territory that is more familiar to scholars of the Left — namely, Thompson Patterson’s remarkable record as an organizer of key Communist and Black radical formations.

These projects included the Soviet Friendship Society; the Vanguard Club (a political forum co-founded with sculptor Augusta Savage); the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (through which Thompson Patterson championed the nine “Scottsboro boys” who had been wrongly charged with and sentenced to death for raping two white women); the International Workers Order; the Harlem Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy; the Harlem Suitcase Theater; the militant Black feminist Sojourners for Truth and Justice; and the New York Committee to Free Angela Davis.

As this list suggests, Thompson Patterson’s biography is something of an ode to organizing. “Organizing is a fine art,” she tells students of her alma mater, Berkeley, “I have worked at it all of my adult life.”

Organizing and Solidarity

Thompson Patterson’s career as an organizer comprises a crucial chapter of the history of Black Left feminism, defined by Mary Helen Washington as the tradition through which Black women “worked to create a sense of international solidarity among women of color, and […] placed black working-class women at the center of their concerns.”(1)

For example, Gilyard shows how Thompson Patterson investigated and promoted female empowerment and women’s lives in the Soviet republics in a manner that complements but also differs from Langston Hughes, whose travel writing has received greater scholarly attention. For one, Thompson Patterson wrote that the legality of abortion was an aspect of Soviet women’s emancipation — an example of feminist standpoint epistemology, as she chose to terminate a pregnancy during her Soviet sojourn.

Thompson Patterson’s volunteer service for the Spanish Republican forces against fascism similarly articulated Black internationalism through women of color’s empowerment. She upheld Salaria Kee, the only African-American nurse in the Spanish Civil War, and the Spanish Communist Dolores Ibarruri (“La Passionara”), as role models for African-American women.

Even Thompson Patterson’s second marriage to the Black Communist lawyer and activist William Patterson, and her experience of mothering a daughter, Mary Louise Patterson (who would become the first African American to complete medical school in the Soviet Union), were powerful if at times ambivalent vehicles for activism.

For better and worse, Gilyard largely avoids bringing Thompson Patterson’s life to bear on historiographic and ideological issues. Even though her sustained engagement with the Black liberation movement invites, if not begs, discussion of Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s “long civil rights movement” paradigm, or of the Left’s intersections with the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights and Black Power movements, these debates are not reprised.

“Madam Moscow”

While Gilyard applies the “Madam Moscow” soubriquet to Thompson Patterson, going so far as to use it to title the chapter on the 1932 USSR trip that she coordinated, he is relatively reserved in his critique of Thompson Patterson’s loyalty to the Soviet Union, which would survive Khrushchev’s 1956 denunciation of Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

He chooses not to comment on the complexity of African-Americans’ strategic identifications with the Soviet project. With its wealth of biographical, cultural and historical research, Gilyard’s book can help us pursue these and other inquiries for ourselves. But there are some missed opportunities at least to signpost key scholarly and political issues.

This is perhaps an outcome of Gilyard’s aim to provide “a psychological or at least interactive depiction” of Thompson Patterson in order to answer the question of why she would have “become politicized and act[ed] as she did?” Gilyard’s provisional answer is that Thompson Patterson’s childhood color consciousness, isolation, and persecution

“…created a passionate yearning for justice, humanism, and community. In her view, this yearning was best consummated through the cultivation of a rebellious identity and participation in radical movements and projects. This story is largely one of a woman who rejected offers and opportunities to construct a sterling mainstream reputation and to pursue a materially comfortable professional life. Instead, despite the privilege of a college education and even her light complexion, she opted to traverse the harder path and committed herself to some of the most difficult struggles of her times for political transformation.” (3)

Privileging the psychological story of a woman who courageously committed to collective struggle over personal success, Gilyard creates a compelling narrative of political development. However, Thompson Patterson’s work and thought should be situated within the historical formation of a community of Black women radicals and of Black left feminism.(2)

This missing context is occasionally jarring, as when Claudia Jones is only sporadically mentioned, despite writing the 1949 article (“An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!”) that provided a major political and philosophical basis for the Sojourners for Truth and Justice with their “Call to Negro Woman” “linking feminist, domestic civil rights, and internationalist human rights visions.” (Gilyard, 171)

Greater attention to broader structural and collective forces, in conjunction with the psychological portrait of the individual, would further enhance our understanding of what was and is historically possible.

As media, politicians and policy makers continue today to enshrine individual advancement, even as it becomes increasingly harder if not impossible to achieve it, it is all the more necessary to understand the passion and the pleasure, as well as the considerable hard work and sacrifice, with which Thompson Patterson gave her life to fighting for the freedom of all people.

Given that Thompson Patterson was unable to finish her memoir — a heartbreakingly riveting account in and of itself — we are fortunate to have Gilyard’s informed, sensitive account of a Black woman of the Left. Her work and legacy, like that of Claudia Jones, Esther Cooper Jackson, Lorraine Hansberry, Vicki Garvin and so many others, must be studied, debated and renewed.

Notes

- Mary Helen Washington, “Alice Childress, Lorraine Hansberry, and Claudia Jones: Black Women Write the Popular Front.” In Left of the Color Line: Race, Radicalism, and Twentieth-Century Literature of the United States. Ed. Bill V. Mullen and James Smethurst. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 2003, 183-204.

back to text - In a similar vein, Charisse Burden-Stelly contends that the biography’s “major weakness is that it is often lacking in careful analysis of the social and political contexts that frame [Thompson] Patterson’s activism.” Charisse Burden-Stelly, “Louise Thompson Patterson and Black Radical Politics,” 12 May 2018. Black Perspectives.

back to text

September-October 2018, ATC 106