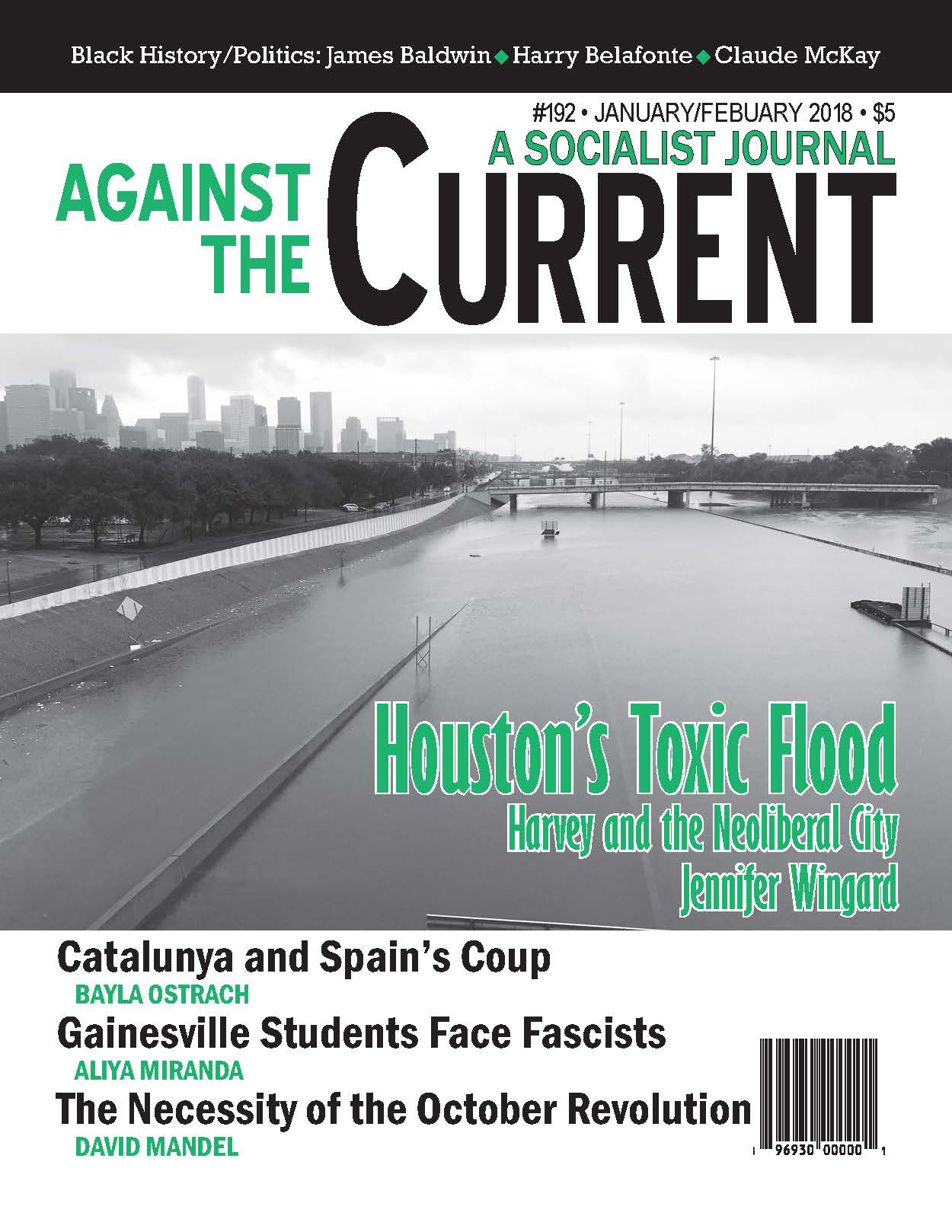

Against the Current, No. 192, January/February 2018

-

Open and Hidden Horrors

— The Editors -

The #MeToo Revolution

— The Editors -

Black Nationalism, Black Solidarity

— Malik Miah -

Harvey's Toxic Aftermath in Houston

— Jennifer Wingard -

Florida Students Confront Spencer

— Aliya Miranda -

How the UAW Can Make It Right

— Asar Amen-Ra -

The Kurdish Crisis in Iraq and Syria

— Joseph Daher -

Kurds at a Glance

— Joseph Daher -

Clarion Alley Confronts a Lack of Concern

— Dawn Starin -

Catalunya: "Only the People Save the People"

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Organizations at a Glance

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Abbreviated Timeline

— Bayla Ostrach - Egyptian Activists Jailed

- On the 100th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution

-

The October Revolution: Its Necessity & Meaning

— David Mandel -

Theorizing the Soviet Bureaucracy

— Kevin Murphy - Reviewing Black History & Politics

-

Race and the Logic of Capital

— Alan Wald - Black History and Today's Struggle

-

Racial Terror & Totalitarianism

— Mary Helen Washington -

Portrait of an Icon

— Brad Duncan -

Lessons from James Baldwin

— John Woodford -

New Orleans' History of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Claude McKay's Lost Novel

— Ted McTaggart - Reviews

-

Language for Resisting Oppression

— Robert K. Beshara - In Memoriam

-

Estar Baur (1920-2017)

— Dianne Feeley -

William ("Bill") Pelz

— Patrick M. Quinn and Eric Schuster

John Woodford

James Baldwin: The FBI File

edited by William J. Maxwell

Arcade Publishing, New York, 2017, 430 pages,

$22.99 paperback.

I Am Not Your Negro

documentary film directed by Raoul Peck

Magnolia Pictures, 2017 release, 93 minutes.

“Milton! Thou shouldst be living at this hour:

England hath need of thee: she is a fen

Of stagnant waters . . . .”

SO BEGAN WORDSWORTH, in his sonnet “London, 1802,” wishing for the return of a great artist of moral and political courage who could “give us manners, virtue, freedom, power” in an era plagued by manifold national disgraces.

So might many of us wish for the reincarnation of someone like James Baldwin as he appears before us in two recent biographical mediums, James Baldwin: The FBI File and the documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Those who hope to fight our way through the Trump era, and come out with a better country than the one now plagued by our own national disgraces, can learn much from reconsidering Baldwin’s life and times as presented in these wonderfully complementary and inspiring works.

In The FBI File, William J. Maxwell, professor of English and African-American studies at Washington University in St. Louis, sets out an interpretive frame, a sort of trifocal lens, through which readers may study his excerpts of the 1,884-page file that J. Edgar Hoover and his minions compiled on Baldwin.

Gathered by spying on Baldwin at home and abroad from at least 1958 to 1974, and perhaps going back as far as 1944, it is the largest file on any Afro-American author.

The entire file is online at Maxwell’s F.B. Eyes Digital Archive at http://digital.wustl.edu/fbeyes. Blacked out by ink, however, are numerous names of FBI agents and also of the sort of “friends” and associates who spied on Baldwin, the sort of routine snitching we have been conditioned to cite as evidence of a police state when it was done by the Stasi in East Germany and other such state agencies.

The three motifs Maxwell lays out in his introduction and in his helpful explanations before each of the 70 chapters are intended to guide readers as they plod and pick through this briar patch of dossiers.

These are: (1) Sex, particularly “queer theory” as it relates to Black Lives Matter and to numerous FBI comments (“Isn’t Baldwin a well-known pervert?” Hoover wrote at the bottom of a typed report). (2) Surveillance, in general the manifold spying of the modern surveillance state and in particular what some Black theorists describe as “white surveillance” of “performances of Black freedom.” (3) The trope of slavery, especially in citing Black-nationalist rhetoric that depicts the Afro-American struggle as essentially the latest expression of an ongoing “revolt of the slaves.”

Maxwell acknowledges that while each of the three lenses may appeal to some wings of the various academic and grassroots identity-oriented movements today, they fail to explain why Baldwin was, till his death in December 1987, a ”first-class threat to J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and its ideal of the American order, racial, sexual and cultural,” or why Baldwin was also the “most revered African American writer of his time.”

I hope to offer explanations for both statuses.

The Threat of Baldwin’s Politics

Missing in Maxwell’s sex/surveillance/slavery optic is James Baldwin’s politics. The USA has a political-economic order, one that underlies the “racial, sexual and cultural” order Maxwell cites. And it is Baldwin’s politics, I will argue, that made him a “first-class threat” to both the reactionary and liberal wings of the U.S. establishment.

Furthermore, it was a politics that emerged through the manifold struggles of left organizations of that day, which included, significantly for him, the movements that brought Orilla (Bill) Miller to his elementary school as a federal Works Progress Administration intern.

As a young white teacher, Miller introduced the bright 10-year-old boy to history and culture, and it was because “she arrived in my terrifying life so soon, that I never really managed to hate white people,” Baldwin says in the documentary.

The FBI itself, Maxwell notes, had a deeper and more respectful view of Baldwin’s political significance than those who dwell today on his sexuality, his delineation of Blackness or even his brilliant prose artistry.

“The founding premise beneath the Bureau’s extensive surveillance of twentieth-century African American authors,” Maxwell writes, “was…in fact, a vision of liberation rather than captivity.”

Maxwell writes:

“Hoover himself possessed an inflated fear and regard for the authors who doubled as “thought-control relay stations,” as he classified them. Authorial relay stations of prominence, Baldwin included, were spared in-person interviews by Bureau agents impressed by their “access to the subversive press,” a megaphone whose range the FBI tended to exaggerate.” (emphasis added—JW.)

It puzzles me that a scholar who has conceded the energetic thoroughness of FBI spying would state in an aside that the FBI exaggerated the significance of the progressive press. (In checking the source for this quotation, I found that Hoover’s comment on the “relay stations” addressed the writings of W.E.B. DuBois in a 1960 memo found in DuBois’s file, not Baldwin’s).

Like DuBois, Baldwin’s politics as revealed in these files were consistently left and outspokenly pro-socialist and anti-imperialist. You just have to dig through the assembled mound of files that contain the true moral of Baldwin’s life story.

One of the earliest spynotes on Baldwin concerned a May 1963 meeting with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) and ten “civil rights intellectuals” headed by Baldwin. He brought, among others, the playwright Lorraine Hansberry, psychologist Kenneth Clark, Harry Belafonte and the actor Rip Torn.

I’ll go into this event in a bit of detail because it represents (1) the sort of political involvement that the files themselves reveal to have been typical of Baldwin’s activism throughout his life, and (2) aspects of Baldwin’s thinking and character that are missing in much of the overheated focus on sex/surveillance/slavery in contemporary academic and movement chatter.

The N.Y. Journal-American Washington correspondent Warren Rogers reported on the meeting. He wrote that while RFK had emerged as an “articulate spokesman” for his country in vexed controversies like the Bay of Pigs, Vietnam and negotiations with developing countries, he was having trouble handling “the racial problem … without any doubt the gravest problem facing the country today.”

Bobby Kennedy, Rogers went on, “had one disastrous sortie into the lofty levels of Negro intellectualism a few days ago. This was his meeting with James Baldwin, the bitter and brilliantly articulate spokesman for the Negro who says, ‘integration now.’”

Kennedy then met with Alabama Governor George Wallace to get another view of the “racial problem,” Rogers continued, and this left him “shaking his head and saying it was like talking to a foreign government, which is just about the way he must have felt after his bout with Baldwin.”

Writing for the Hearst newspaper syndicate — that era’s equivalent of Fox News — Rogers then predicted that RFK “will not make such mistakes again. He has learned that little can be gained and much can be lost by trying to deal directly with people like Wallace and Baldwin, who are at opposite ends of the integration-segregation spectrum.” (President Trump was mucking in deep footsteps when he found equivalency between neo-nazis and anti-racists!)

The FBI’s Concerns

The FBI placed the Hearst article in Baldwin’s file because it had generated a request for more information about Baldwin from Clyde Tolson, Hoover’s second-in-command at the Bureau and, reputedly, in bed. An unidentified agent responded by memo on May 29, 1963, beginning by acknowledging Baldwin’s importance as a cultural icon who “has become rather well-known due to his writings dealing with the relationship of whites and Negroes.”

Then followed a list of the sort of activities that I argue led the FBI to compile its lengthy dossier on Baldwin. “In 1960,” the memo continued, “he sponsored an advertisement of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.” In capsule form, the file went on to list what amounted to Baldwin’s real sins in the Bureau’s eyes, a list drawn from this single memo but typical of many dozens you can read in this book:

“In 1961 he sponsored a news release from the Carl Braden Clemency Appeal Committee distributed by the Southern Conference Educational Fund [SCEF], the successor to the Southern Conference on Human Welfare cited as a communist front by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA). Braden was a communist convicted of contempt of the HCUA.

“In 1962 Baldwin signed a clemency petition for Junius Scales, a communist convicted under the Smith Act.

“In April 1961 he sponsored a rally to abolish the HCUA.

“He has advocated the abolishment of capital punishment.

“[He has] criticized the Director stating that Mr. Hoover ’is not a lawgiver, nor is there any reason to suppose him to be a particularly profound student of human nature. He is a law-enforcement officer. It is appalling that in this capacity he not only opposes the trend of history among civilized nations but uses his enormous power and prestige to corroborate the blindest and basest instincts of the retaliatory mob.

“He has also indicated he feels the Attorney General and the President have been ineffective in dealing with discrimination and in this connection has urged the removal of the Director.”

After reading this memo, I diverted my attention to learn about the Junius Scales case via Wikipedia — then went on to read Scales’ book on his organizing textile workers in North Carolina across racial lines, his falling out with the Communist Party and subsequent conviction by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1961 and imprisonment for refusing to “name names” to the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Scales’ name, however, does not appear in the index of James Baldwin: The FBI File. Nor does that of Carl Braden, the courageous white anti-racist journalist.

Another file, from 1963, reports on Baldwin’s defense of William Worthy, an Afro-American journalist who defied U.S. attempts to curb his travel to Cuba and “Red China” and fought successfully both to recover the U.S. passport illegally seized from him in 1956 and to overturn his prison sentence.

Baldwin was a leader of the American Rights to Travel Committee that supported Worthy whose name isn’t found in the index either.

An agent’s memo from May 13, 1966, states that the following instance of surveillance was in response to an inquiry from “Mrs. Mildred Stegall, White House Staff.”

“Captioned individual [i.e. James Baldwin —JW], prominent author and playwright, has been the subject of security-type investigation conducted by the FBI which has revealed his association with individuals and organizations of a procommunist nature.

“In July, 1965, he was the author of a form letter urging recipients to renew their subscriptions to ‘Freedomways’ magazine which is reportedly staffed by Communist Party (CP) members or sympathizers including Esther Jackson, its Managing Editor, who is the wife of James Jackson, a member of the National Committee of the CPUSA…”

Neither of the Jacksons appears in the index so, again, it takes a dogged reader to unearth the socialist/communist context within which Baldwin agitated.

A person doesn’t make the index if he or she is cited only in the FBI files. Because many of Baldwin’s activities with members of Communist and Socialist groups are not in the index, readers today, especially young ones, will find it hard to discover and track down the rich history surrounding those who don’t make the index.

At the risk of being repetitious, I want to drive this point home: To me this excellent book on state censorship is itself a symptom of a widespread sort of “lite” censorship common in academia and the news media in our country today.

Memo after memo, report after report, reveal that the government’s official position was that efforts to desegregate the country were out-and-out “communist front” campaigns. And perhaps that was so. But doesn’t that suggest that a communist front was rather a good thing?

Battling Racism

James Baldwin was swept up in this massive surveillance simply because he was a writer who stuck his neck out farther and more often than his peers. What these memos and the many like them show is that equating anti-racism with communism was the official stance of the U.S. establishment from the White House down.

That’s why agents reported on Baldwin’s relationship with Martin Luther King, Jr. and all other civil rights leaders of the day in every civil rights organization from the NAACP to CORE to SNCC. But Baldwin also met with and wrote about the Nation of Islam, discussing a wide range of issues with both The Honorable Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X, and also with Huey P. Newton and the Black Panthers. The FBI documented all such contacts as constituting possible threats to “national security.”

Baldwin was often invited either alone or on panels to discuss the “race problem” on network TV. On occasion, the United States Information Agency edited such programs for audiences both home and abroad, so as to eliminate Baldwin’s condemnation of the Mississippi champion of segregation and bigotry, Sen. James Eastland.

Meanwhile Hoover, responding to a letter from one of his admirers who’d asked in reference to Baldwin whether Hoover could “tell us if a man is a known communist,” said such information was “available for official use only pursuant to regulations of the Department of Justice.”

Communist or not, Baldwin like many other activists was on the FBI’s Security Index containing untold thousands of citizens “who in a time of emergency are in a position to influence others against the national interest.”

Such persons, Maxwell observes, could be arrested and detained without legal representation or trial. The Index was supposedly eliminated in 1971, but considering all known precedents to such actions, it was most likely simply reclassified and renamed.

“Destroyed by a Plague Called Color”

In October 1963, Baldwin joined Dick Gregory in a trip to Selma, Alabama, to watch 300 African-American citizens attempt to register to vote.

He “saw, at first hand,” Maxwell writes, “FBI agents refuse to intervene as Sheriff Jim Clark beat and arrested several would-be voters. Years later, Baldwin recalled in an essay that he had asked an FBI representative on the scene if the sheriff — a man whose moral life seemed to be ‘destroyed by a plague called color’ — had ‘any right to throw us off Federal property. No, is the answer, but we can’t do anything about it.’”

The FBI spies were not alert to the significance of Baldwin’s consistent diagnosis of how severely white racism constituted a plague that infected and impaired the minds of white Americans.

One of the strengths of Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro is that it provides clearer examples of Baldwin’s profoundly anti-racist, humanistic personal creed.

On the surface, the film seems focused intently on race. It is structured as a presentation of Baldwin’s meditations on the assassinations of three Black American heroes, Medgar Evers (1963), Malcolm X/Malik el-Shabazz (1965) and Martin Luther King, Jr. (1968).

But to me, director Peck’s nominal structure is something of a red herring, like Maxwell’s focus on academic theorizing in his book’s introduction. These are hooks, marketing ploys of a sort, ways to get publishers and producers to back a project as provocative but also safe ideologically.

The film’s content, however, far outstrips and undercuts any easy notions of what it, or Baldwin, is about. Take the title, I Am Not Your Negro. It prompted me at first to reply sarcastically, because I’ve always detested the term, “Well, then, whose Negro are you?”

But here’s how the film opens: It’s a Dick Cavett Show from 1968 and the TV host begins: “I’m sure you still meet the remark that, they say, ‘Why aren’t they optimistic? It’s getting so much better. … They’re in all of sports. There are Negroes in all of politics. They’re even accorded the ultimate accolade of being in television commercials now.’ I’m glad you’re smiling. Is it at once getting much better and still hopeless?”

“Well, I don’t think there’s much hope for it, you know, to tell you the truth,” Baldwin replies. “As long as people are using this peculiar language. It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro here, to the Black man here; that’s a very vivid question for me, you know, but the real question is what’s going to happen to this country. I have to repeat that.”

The film then shows white supremacist and police violence spanning the decades from the 1950s to the present. But what was Baldwin getting at when he referred to “this peculiar language”?

We can formulate an answer if we follow Baldwin’s other probing of the subject of race. Peck, a Haitian American who studied economics in the German Democratic Republic and film in the Federal Republic of Germany, gives us another perspective on that same famous meeting with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy that The FBI Files also highlights. Samuel L. Jackson narrates Baldwin’s account:

“We [the ten Black activists at the meeting] wanted him to tell his brother, the president, to personally escort to school on that day or the day after a small Black girl already scheduled to enter a Deep South school the next day. That way, we said, it would be clear that whoever spits on that child would be spitting on the nation. He did not understand this, either. He said it would be a meaningless moral gesture.

“’We would like,’ said Lorraine [Hansberry], ’from you a moral commitment.’ He looked insulted, seemed to feel that he’d been wasting his time. Well, Lorraine sat still, watching all the while. She looked at Bobby Kennedy who perhaps for the first time looked at her. But I’m very worried, she said, about the state of the civilization which produced that photograph of that white cop standing on that Negro woman’s neck.

“Then she smiled. And I’m glad that she was not smiling at me. ’Good-by Mr. Attorney General,’ she said, “and turned and walked out of the room.”

Baldwin identified RFK’s moral failure as symptomatic of a broader failure shared by the White House, FBI, State Department, CIA and liberal whites as well as blatant racists, the effects, in a word, of a “plague called color.”

Of the killing of four Afro-American girls in the Ku Klux Klan’s 1963 bombing in Birmingham, Baldwin says: “White people don’t want to believe, still less to act on the belief, that what is happening in Birmingham is happening all over the country. They don’t want to realize that there is not one step morally or actually between Birmingham to Los Angeles.”

But Baldwin tried not to lose hope that whites would one day understand that a log of race is lodged in their eyes, that they have inherited a grave defect and would need to recognize it if they hoped to cure it.

As the film runs, he recasts his observations on notions of race many times, hoping that one verbal expression or another might score a telling hit against the mental blockage and dislodge that log:

“All the Western nations have been caught in a lie. The lie of their pretended humanism. The West has no moral authority. American prosperity cost millions of people their lives. They cannot imagine the price paid for their prosperity by their victims…

“[Y]ou wonder … how you are going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here. I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human. I base this on their conduct, not on what they say. And this means that they have become in themselves, moral monsters.”

Baldwin trounced William F. Buckley, Jr., the rightwing champion of intellectualized conservatism (and, as the FBI Files shows, a darling of the FBI) in a 1965 Cambridge University debate on the question “Is the American Dream at the Expense of the American Negro?”

Peck shows the British students rising to their feet to loudly proclaim his victory after he had roused them with his surprising and stunning peroration: “What has happened to white Southerners is much worse than what has happened to Negroes there.”

Perhaps Baldwin’s most acidic commentary on race, and the best definition of what he meant by the phrase “I am not your Negro,” can be found in a documentary about a documentary. Richard O. Moore had directed a documentary Take This Hammer about Baldwin in 1963, and some footage was later released in an offshoot documentary in which Baldwin soliloquized in a 45-minute outtake, a Socratic improvisation on the subject:

“I’ve always known that I’m not a nigger. But if I am not, who is? . . . I am not the victim here. But you still think, I gather, that the Negro is necessary. Well he’s unnecessary to me, so he must be necessary to you. So I give you my problem back: you’re the nigger, baby, not me.”

(For an absorbing discussion of the Moore documentary see Professor Rachel Brahinsky’s “Tell Him I’m Gone” in A Political Companion to James Baldwin, edited by Susan J. McWilliams, 2017, University Press of Kentucky. The book contains other excellent appraisals of Baldwin as a philosophic writer.)

Where Baldwin Leads

One can say that both the book and film under review show that Baldwin fought racism on two fronts: forging unity among Afro Americans who have been oppressed and discriminated against on the basis of racist hierarchies, while also expanding the struggle and participating in a broad, class conscious political front that understood and openly espoused the ideals of socialism.

The success, a welcome surprise to me and many others, of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign means that there is an opportunity now to put the struggles for social justice and democracy together with the struggle for greater economic and political power — by all who stand to gain from better and more affordable health care, better and more affordable education, a cleaner environment, healthful food, livable housing, and effective curbs on abuse of power by the One Percenters and their hirelings.

The socialist project and socialist agenda can and must now be spoken about openly, loudly and often. The only alternative is common ruin.

What Wordsworth meant by wishing for a Milton, and what I mean by wishing for a Baldwin, is wishing for grassroots groundswells of a “Human identity politics” that emerges from a sense of humanity, or even Earth-lifeform-identity.

That is the sort of friction and ferment that gives rise to artists like Milton and Baldwin. They don’t come down to us. They grow up out of us.

January-February 2018, ATC 192