Against the Current, No. 190, September/October 2017

-

The War Is At Home

— The Editors -

When White Supremacists March

— Michael Principe -

Choices Facing African Americans

— Malik Miah -

How the UAW Lost at Nissan

— Dianne Feeley -

Did Scandal Tip the Balance?

— Dianne Feeley -

NSA's Cyberwarfare Blowback

— Peter Solenberger -

The Murder of Kevin Cooper

— Kevin Cooper -

Attica from 1971 to Today

— interview with Heather Ann Thompson -

The Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti

— Marty Oppenheimer -

Mourn Liu Xiaobo, Free Liu Xia

— Au Loong-Yu -

Under Attack at San Francisco State University

— Saliem Shehadeh -

Dawn of "Total War" and the Surveillance State

— Allen Ruff -

Solidarity Message to Egyptian Website

— The Editors - Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion & Rise of the Neoliberal State

— Jordan T. Camp -

Chronicle of Black Detroit

— Dan Georgakas -

For Mike Hamlin

— Michele Gibbs -

Mike Hamlin (1935-2017)

— Dianne Feeley - Suggested Readings on/about Detroit's 1967 Rebellion

- Reviews

-

BLM: Challenges and Possibilities

— Paul Prescod -

The People vs. Big Oil

— Dianne Feeley -

Immigration's Troubled History

— Emily Pope-Obeda -

Paradoxes of Infinity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Mourn, Then Organize Again

— Michael Löwy -

Making Their Own History

— Ingo Schmidt -

The Wheel Has Come Full Circle

— Mike Gonzalez

Michael Principe

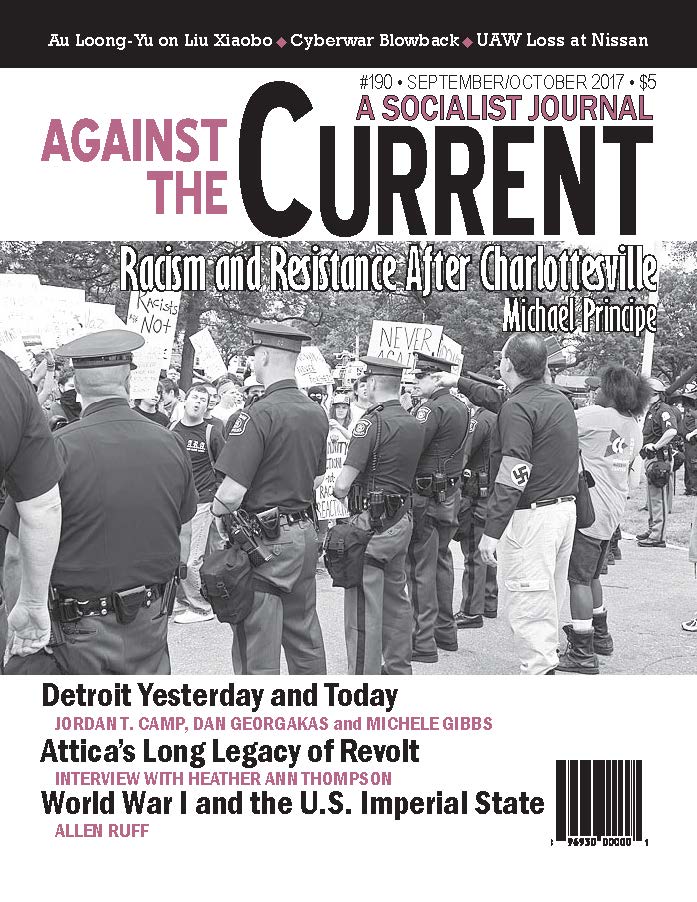

THE FIRST IMAGES to emerge from the violent white supremacist “Unite the Right” gathering in Charlottesville, Virginia were of mostly clean-cut, young, white men marching, carrying torches and chanting “We will not be replaced” and “Blood and soil.”

The rally, featuring white nationalist groups such as the Nationalist Front and the League of the South as well as white supremacist “superstars” like Richard Spencer and David Duke projected violence from its first moments.

This was part of its point: Intimidate the Black community, the people of Charlottesville, and everyone who disagrees with them through a show of paramilitary force. This led to the callous murder of Heather Heyer, the brutal beating of Deandre Harris, and other injuries.

While this was supposed to be the largest gathering of white supremacist and openly fascist forces in a decade, smaller gatherings have become increasingly common, including two earlier demonstrations in Charlottesville precipitated by the proposed removal of a Robert E. Lee monument erected in 1924. Questions of history, its meanings, and interpretations loom large.

Playing with Imagery?

The historical iconographies of several eras intersect in these events. With regard to Nazi imagery, some have tried to explain away its increasing prevalence by suggesting that young people don’t really understand what they are doing or are involved in relatively innocent youthful transgression.

A recent USA Today article claimed that the swastika “is more popular than ever among non-ideological haters — kids, vandals, anyone out to shock or express a grudge against someone who happens to be Jewish, black, Hispanic or gay.”

This sensibility is much too sanguine. Even if many amongst the organized fascist marchers in Charlottesville chanting “Blood and Soil” likely had no very clear sense of its links to pure German bloodlines and ancient agrarian culture, perhaps we can now better see each of these bits of “play acting” as a sign of a real threat characterizing the current moment. The distance between a “non-ideological hater” and organized defenders of white supremacy is at best exceedingly narrow.

Dangerous identifications with fictionalized histories are also a dominant feature of the struggles across the South to remove Confederate monuments and memorials that have become flashpoints for white supremacists. Many of these originate from periods long after the Civil War. They represent the assertion of white, ruling-class power and are connected to the histories of Jim Crow and resistance to desegregation.

While Virginia continues to publicly honor Robert E. Lee, here in Tennessee the figure of Nathan Bedford Forrest is ubiquitous. While his defenders most often revere him as a brilliant military strategist, he was also a slave trader and a leader of the Ku Klux Klan. His bust sits in the state capital building in Nashville, his statue stands in Memphis, a state park bears his name, as does the ROTC building at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro.

Much of Tennessee’s celebration of Forrest dates from the 1950s with its bitter fights over desegregation. Although the city of Memphis and the administration of MTSU have recommended the removal of these markers, the Tennessee Historical Commission, whose powers have recently been enhanced by the Republican super-majority holding sway in the legislature, has so far blocked any change.

The fight to have these symbols of white supremacy removed has involved significant community organizing, open forums where both bluntly aggressive and veiled racist rhetoric was commonly on display.

Racist Violence is Now

These fictional histories of fascists and Confederates, even as they evoke the ugliness and violence of the past, allow many of those involved as well as those who observe or report events to distance themselves from the current racist and violent reality by claiming that it is not really the same as the dangers found in the historical past.

Unfortunately, given recent and not so recent events, those who oppose and are endangered by the organized racists and their periphery need to prepare and proceed with some expectation of violence.

In addition, a deeply ingrained history of liberal individualism continues to contribute to the mounting possibility of racist violence. “Free Speech” is increasingly a slogan of the far right which has proved effective in gaining passive support from liberals and legal backing from the courts.

The sensibility that speech should not be regulated is connected to a larger and more dangerous liberal neutrality, lending at least a familiar rhythm to President Trump’s despicable remarks condemning the “hatred, bigotry, and violence” in Charlottesville “on many sides. On many sides.”

Obviously, neutrality here is carried to its most bizarre and ugly extreme and has been rightly condemned by many liberals, although similar statements can be found in the mainstream media comparing violent neo-Nazis to members of Black Lives Matter. In this way, though, the President has essentially green-lighted more white supremacist organizing and violence.

This should be unsurprising, given the way Trump encouraged violence during his campaign and by the fact that those gathered in Charlottesville represented his most energetic and enthusiastic supporters.

A statement like this coming from the President, regarding a clear case of domestic terrorism, represents a victory for the far right and has been celebrated as such by neo-Nazis on their Daily Stormer website. We should expect the fascists, white supremacists and neo-Confederates to seize this opportunity and continue to maintain prominence through public gatherings and high-profile speaking engagements.

While Republicans and mainstream conservative media have cozied up to these forces for some time, Trump’s nearly explicit support will allow for and encourage those of his supporters who are not and never will be members of fascist organizations to explain away and otherwise make light of the dangers of these forces, thereby enabling broader expressions of racism.

Pushback and Self-Defense

Hours after the horrific events in Charlottesville, substantial pushback began with thousands of people across the South and the nation rallying against white supremacy. This pushback will continue despite the real threat of right-wing terrorism.

I attended a solidarity rally in Murfreesboro on Sunday, August 13 after the Charlottesville violence. Several hundred people came together on short notice in a town where the local Mosque has been regularly vandalized, and where a short time ago hundreds gathered to protest Trump’s racist travel ban only to be harassed by a motorcycle gang revving their motors, flying Trump flags and trying to break up the rally.

Whenever a loud engine was heard Sunday, one sensed a bit of anxiety move through the crowd. Still, people showed up here and elsewhere. We should expect and encourage them to show up in larger and larger numbers, while recognizing the need for organized self-defense.

September-October 2017, ATC 190