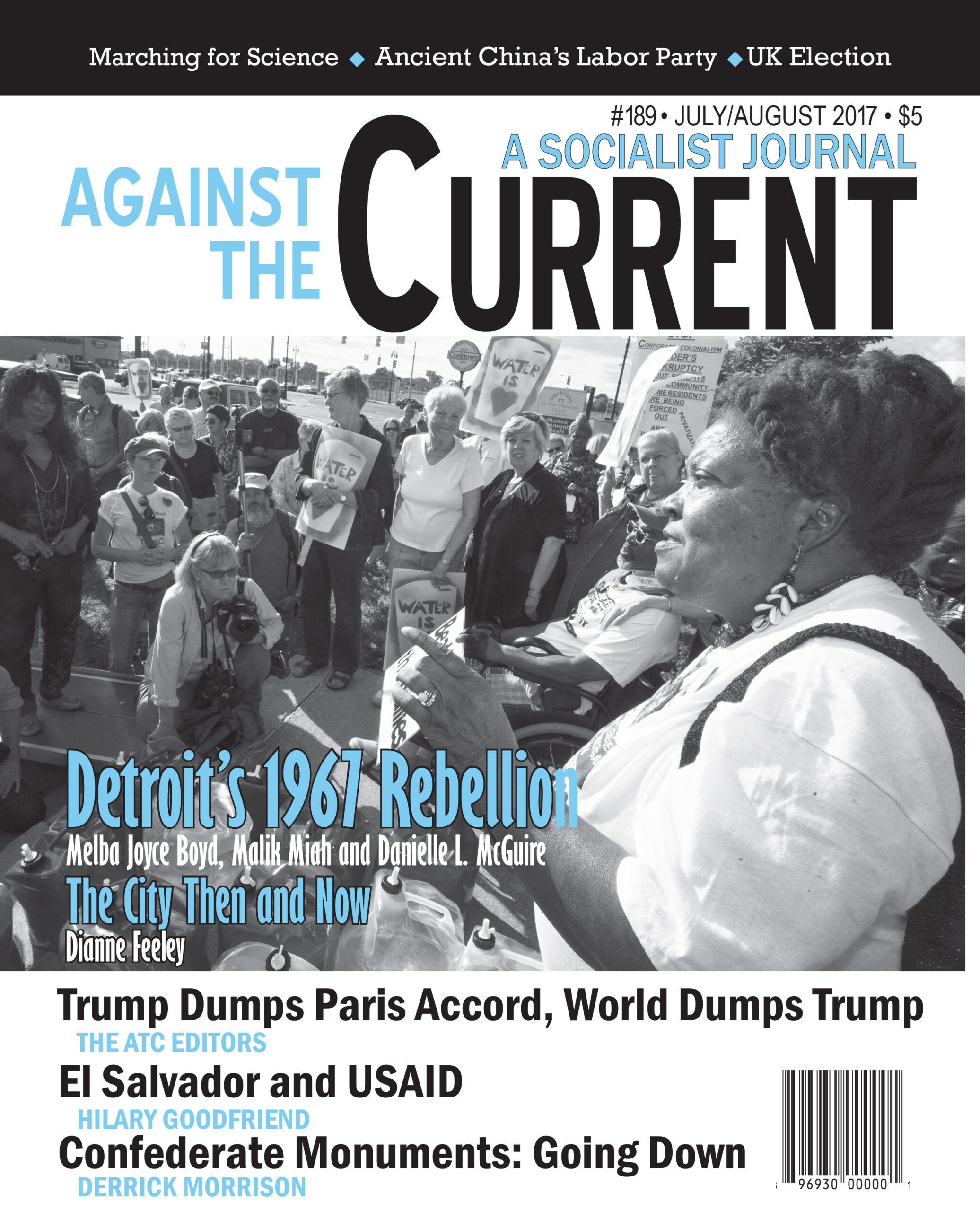

Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Patrick M. Quinn

Reform or Repression:

Organizing America’s Anti-Union Movement

By Chad Pearson

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016, 312 pages, $55 cloth.

THE FINAL TWO decades of the 19th century, beginning with the great strike wave of 1877, and the first two decades of the 20th century were a period of intense class combat in the United States. The industrial working class struggled with the financial and industrial employing class in a bitterly fought battle that established an initial relationship of forces between the two emerging classes.

Chad Pearson’s new book recounts a critical component of that momentous struggle — the efforts of the employing class to establish an “open-shop” (i.e. non-union) movement, in order to defeat union attempts at organizing workers at the point of production and establishing what were characterized as workplace “closed shops” (i.e. unionized shops).

Pearson’s book is without a doubt among the best labor histories to be published in recent years. In keeping with the modern trend in labor history, this is not a labor history in the “traditional” sense of the term. Rather than being based on union minutes and other records and on union publications, Reform or Repression is almost exclusively based on sources produced by the employing class.

These include employer association magazines and other publications, speeches and writings by leaders of the employers’ associations and the “open-shop” movement, newspaper accounts about the movement, etc. Pearson uses the rhetoric of the “bosses” to document their efforts to prevent unions from organizing their workplaces.

Pearson concentrates on the metalworking industry, with the factory owners’ attempts to defeat the Iron Molders Union and the International Association of Machinists organizing efforts.

In his first of six chapters, Pearson comprehensively reviews the origins of the “open shop” movement in the United States. Chapter Two, perhaps the most informative and interesting, examines how the “open shop” movement embraced the rhetoric and values of the “progressive” movement in an effort to shape public opinion and steer it towards support for the concept of “open shops.”

Pearson reveals how “progressives” such as President Theodore Roosevelt, Kansas City’s George Creel (who later became head of U.S. war propaganda during World War I), the famous “muckraker” Ray Stannard Baker and others enthusiastically supported the “open-shop” movement. The the movement employed the concepts of “freedom,” “liberty” and “democracy” to further anti-union campaigns.

Cynical Manipulation

Some leaders of the “open-shop” movement actually believed in and supported the actions and values of the progressive movement, especially its efforts to eliminate child labor, establish safer working conditions, and break up trusts and monopolies. But the great majority of the leaders cynically articulated “progressive” values and incorporated them into their rationale for opposing union organizing efforts.

Does all this sound familiar? The origin of the “the right to work” concept, which prevails in 2017, had its inception well over a century ago as did the concept of “free labor.” The employers argued that the concepts of the “right to work” and “free labor” were the very essence of democracy. These became their mantra to keep unions out of their workplaces.

By the beginning of the 20th century the language of “free labor,” which had originally described white workers, primarily in the North as opposed to African-American slave labor in the South, had evolved to describe workers to be “free” to reject membership in unions.

Pearson’s following four chapters are case studies of the employers’ “open shop” campaigns to win hegemony in the industrial cities of Cleveland, Buffalo, and Worcester, Massachusetts as well as in the southern United States (which is today a paradise for “open shop” proponents).

In these chapters Pearson discusses the rhetoric and “values” of the “open shop” movement, and documents how the employing class in these three industrial cities and in the South defeated unions and union strikes by violent means. These were particularly carried out by the police, through importing thousands of strike-breaking workers from other cities, and by availing themselves of anti-union court injunctions.

In his chapter about Cleveland, Pearson recounts the role reversals of a one-time union official/organizer who became one of the main leaders of the “open-shop” movement and of a lawyer who originally was the leading legal representative of the “open shop” movement, but switched sides and became an ardent pro-union attorney.

The chapter on Buffalo depicts how the “open-shop” movement used the assassination of President William McKinley in Buffalo by the anarchist Leon Czolgosz, a follower of Emma Goldman, as a pretext for smashing the union movement in that city, thereby “avenging” McKinley’s death. Pearson’s case study of the “open-shop” movement in Worcester illustrates how successful the “open-shop” movement was in defeating union organizing efforts in that city.

Pearson’s final chapter discusses the “open-shop” movement in the South. He focuses on the career of a former Confederate soldier and early member of the Ku Klux Klan who became one of the most passionate advocates of the “open shop” movement in the various cities where he was a prominent businessman.

Reform or Repression is a truly great read, especially today when union membership has fallen to a historical low. Concepts such as “the right to work” prevail not just in the southern United States but more recently in the Midwest. The employing class today deploys the same rhetoric, concepts and values that it did more than a century ago, including the myth that we live in a classless society in which everybody is “middle class,” enjoying ubiquitous “freedom” and “liberty” in the world’s greatest “democracy.”

July-August 2017, ATC 189