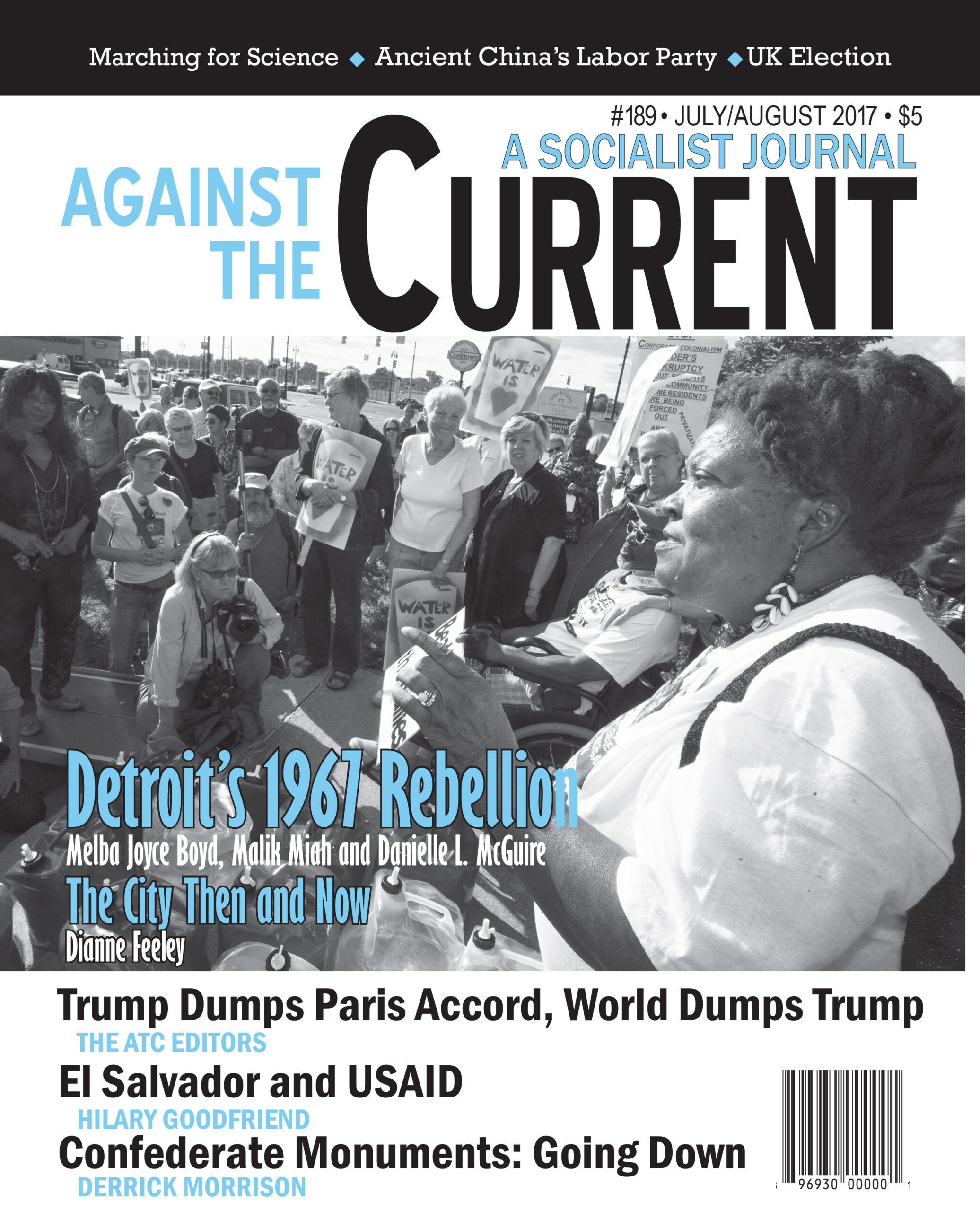

Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Danielle L. McGuire

Danielle L. McGuire is an associate professor of history at Wayne State University and author of the award-winning book At the Dark End of the Street, a study of the struggle against the rape of Black women in the 1940s South that brought together the key figures, including Rosa Parks, who would spearhead the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. The following account is abridged from an anthology, Detroit 1967, just published by Wayne State Press. McGuire has uncovered material that hadn’t previously come to light. Thanks to the author for permission to publish this excerpt.

IT WAS THE early morning hours of July 26, 1967, the third night of the Detroit rebellion. A flurry of Detroit policemen, National Guardsmen and State Police officers, led by David Senak, a 23-year-old vice cop who normally worked the late night cleanup crew or the “whore car,” and two of his colleagues, raided the Algiers Motel after hearing reports of heavy “sniper fire” nearby.

The Algiers had been a stately manor house in the Virginia Park neighborhood of central Detroit. By now it was a relatively seedy place, what the writer John Hersey called a “transient” hotel, with a reputation among police as a site for narcotics and prostitution. But that night, because of the uprising and citywide curfew, many people sought refuge at the Algiers, including two white runaways from Ohio, a returning Vietnam veteran and the friends and members of the Dramatics, a Doo-Wop group.

According to one witness, it was a “night of horror and murder.” Just past midnight, police and soldiers tore through the motel’s tattered halls and rundown rooms with shotguns and rifles. They ransacked closets and drawers, turned over beds and tables, shot into walls and chairs, and brutalized motel guests in a desperate and vicious effort to find the “sniper.”

At some point during this initial raid, David Senak and Patrolman Robert Paille encountered Fred Temple, a teen on the phone with his girlfriend. Senak and Paille barged into the room, startling Temple, who dropped the phone. Senak and Paille fired “almost simultaneously” at Temple, who crumpled to the ground in a pool of blood.

Failing to find any weapons, Patrolman Senak ordered all the guests against the wall in the first floor lobby. One of the young Black men at the hotel that night, 17-year old Carl Cooper, rushed down the stairs and came face to face with a phalanx of heavily armed police and Guardsmen.

A witness heard Cooper say “Man, take me to jail — I don’t have any weapon” just before hearing the gunshot that tore through his chest.

Police herded the other guests, a group of young Black men and two white women, past Cooper’s bloody corpse, into the gray and beige magnolia-papered lobby, and told them to face the east wall with their hands over their heads. Even though two young men were already dead, the lineup was the beginning of what John Hersey called the “death game” in his 1968 book The Algiers Motel Incident.

The details of exactly what happened next are complicated and convoluted; clear memories forever lost to the chaos of the moment, the tricks of time, and the disparate recollections of the survivors traumatized by violence and terror. But the gist of what we know is that three Detroit policemen — David Senak, Ronald August, and Robert Paille — and Melvin Dismukes, a private guard, took charge of the brutal interrogation. They wanted to know who had the gun, who was the “sniper” and “who was doing the shooting.”

When the young men and women lined up against the wall denied shooting or having any weapons, the officers mercilessly beat them, leaving gashes and knots on the victim’s heads and backs. According to one witness, a police officer “struck [a] Negro boy so hard that it staggered [him] and almost sent him down to his knees.”

A military policeman, part of the contingent of federal paratroopers and National Guardsmen sent to help restore order in Detroit, who arrived at the Algiers in the midst of the raid, said he saw a Detroit patrolman “stick a shotgun between the legs of one male and threaten to ‘blow his testicles off.’”

Senak and his colleagues raged against the two white women working as prostitutes at the Algiers, Karen Malloy and Juli Hysell, calling them “white niggers” and “nigger lovers.” Both women testified that police ripped off their dresses, pushed their faces against the wall, and smashed their guns into the young women’s temples and the small of their backs.

“Why you got to fuck them?” David Senak sneered, “What’s wrong with us?” Another witness heard one of the cops say “We’re going to get rid of all you pimps and whores.”

The “Death Game”

Then, the “death game” really began. One by one, the police pulled the unarmed men into different rooms and interrogated them at gunpoint. Roderick Davis, the stocky Dramatics singer who sported a stylish conk and moustache, told the FBI that David Senak took him into a room, forced him to lie down, then shot into the floor. “I’ll kill you if you move,” Senak said as he left the room and returned to the lobby.

“Want to shoot a nigger?” Senak asked Warrant Officer Theodore Thomas, as he grabbed the diminutive, baby-faced nineteen-year-old Michael Clark out of the line, pulled him into the same room, pushed him down and fired at the ceiling.

Senak told Thomas to stay with Davis and Clark and keep quiet. Then Senak returned to the lobby and, according to others, handed 28-year-old DPD Officer Ronald August a shotgun. “You shoot one,” he ordered.

“Now comes the tragic part,” August wrote in a statement five days after the Algiers assault. With help from Norman Lippitt, the lead attorney from the Detroit Police Officers’ Association, August described the circumstances under which he shot and killed 19-year-old Aubrey Pollard.

In that final “official” statement, which Lippitt likely typed up, August claimed that Pollard lunged at him and tried to take his gun, and that he had no choice but to defend himself by fatally shooting the Black teenager.

But that self-serving justification was not in August’s original written or oral statements. His first confession, after some sleepless nights, was to his sergeant, whom he pulled aside to quietly say he shot a young man at the Algiers Motel. He mentioned nothing about self-defense — that part came later.

When the FBI began an investigation of the police for violating the civil rights of the youth they killed, even J. Edgar Hoover had to admit, privately at least, that their official statements were “for the most part untrue and were undoubtedly furnished in an effort to cover their activities and the true series of events.”

The surviving witnesses’ testimony contradicted August’s claim of self-defense. After hearing the thud of Aubrey Pollard’s body on the floor and seeing Patrolman August flee out the front door where he vomited near a tree, police ordered the remaining survivors, terrified and spread-eagle against the blood-spattered lobby wall, to leave.

The white women were bruised and nearly naked, their torn clothes lay in a heap on the floor. “Start walking with your hands over your head,” a cop said. “If you look back, we’ll kill you.” As Roderick Davis, Michael Clark, and the others staggered toward the French doors that opened to the Algiers’ back porch, they passed Carl Cooper’s prostrate body.

The young survivors from the Algiers crossed through the alley to Woodward Avenue. National Guardsmen on patrol at the Great Lakes Mutual Life Insurance Building across the street, who had no knowledge of the horrors nearby, held up their shotguns and demanded they get down on the ground and submit to a search.

“What you been doing?” a Guardsman shouted. “Why you walking home?” When Roderick Davis tried to tell them what happened, the Guardsman said, “too bad. Keep walking. You niggers are always starting some kind of trouble.”

A mere 30 minutes after police burst through the Algiers’ back door in a crazed search for snipers, Clara Gilmore, the African-American motel clerk, called the morgue and asked them to collect the three bodies that were abandoned and discarded as casualties of the riot.

The person working the phones at the morgue notified the police. When Detroit Homicide detectives arrived at the Algiers an hour or so later, they reported three young Black men had “apparently” been “shot to death in an exchange of gunfire.”

The Detroit News briefly mentioned the deaths the next morning — the result, it said, of a “gunfight.” “Sniping” from “the roof and windows on all floors of the Algiers,” the News reported, kept the “police and guardsmen pinned down for several minutes before the firing stopped.”

But witnesses told nearly anyone who would listen that there was no shootout. The police, they said, committed murder.

Investigating the Facts

Two intrepid reporters from the Detroit Free Press, Barbara Stanton and Kurt Luedtke, weary but wired from the nonstop riot coverage, also thought something was unusual. “Three deaths on one night,” as Luedtke put it, just felt wrong.

They visited the crime scene and wondered why, if there was a shootout as the homicide detectives claimed, no weapons had been recovered? And how, if the police and army were pinned down by gunfire, there were so few bullet holes in and around the motel?

Luedtke and Stanton began their own investigation. Their findings and subsequent riot reporting earned the Detroit Free Press a Pulitzer Prize. More importantly, their steady investigatory skills and courage to ask hard questions during an unquestionably emotionally-charged and devastating week that made it all too easy to assign blame and move on, helped push the city prosecutor to charge the police with murder, and compelled Congressman John Conyers to request an FBI investigation as insurance against a complete whitewash.

It was a Free Press article that riled up 29-year-old Kenneth G. “Red” McIntyre, a towering red-headed Assistant U.S. Attorney, who had just returned to Detroit from four harrowing years spent investigating voter fraud and racial terror in Mississippi and Alabama.

Reading about “three dead kids, cops kinda iffy about what happened,” he said, “so incensed me that I called Washington and I said, ‘we’ve got to do something and I’d love to be part of it.’” He got his investigation and ultimately led a major federal civil rights trial that helped expose systemic racism and injustice in the North.

Red McIntyre’s hunger for justice was matched only by the passion and dedication of John Hersey, who came to Detroit in the waning days of the summer of 1967 to report upon the most destructive urban uprising in United States History. Everywhere he went, he said, “the Algiers Motel kept insisting upon attention.”

The case, Hersey said, had “all the mythic themes of racial strife…the arm of the law taking the law into its own hands; interracial sex; the subtle poison of racist thinking by ‘decent’ men who deny they are racists …ambiguous justice in the court; and the devastation in both Black and white human lives that follows in the wake of violence as surely as ruinous and indiscriminate flood after torrents.”

Hersey interviewed nearly everyone involved in the case and then cobbled together the transcripts into a book. He hoped it would help change hearts and open minds when it was published in 1968. In a tragic twist, however, it served to close off one avenue towards justice when Norman Lippitt of the DPOA argued that the publication by Alfred Knopf of The Algiers Motel Incident was too inflammatory and made a fair hearing for the police impossible.

Justice Denied

Lippitt was thrilled to be granted a change of venue to the nearly all-white town of Mason, Michigan, the Ingham County seat where three decades earlier the Black Legion, a Ku Klux Klan offshoot, had terrorized Malcolm X’s family. By then, John Hersey had gone back to Yale where he worked as a professor.

Heroic efforts by the local and federal prosecutors to expose the cops’ false statements, probe Detroit’s history of discrimination and inequality, and to contextualize the summer uprising in a past littered by economic and racial inequality did little to change the white jurors’ hearts and minds.

Both major trials — the 1968 state murder trial in Mason and the 1970 federal civil rights trial led by Red McIntyre, in Flint, Michigan — ended in acquittals.

Fred Temple’s mother, who watched the proceedings with increasing hopelessness, said that the jury’s decision was just the “latest phase of a step-by-step whitewash of a police slaying.”

State Senator Coleman A. Young, who would go on to become Detroit’s first African-American mayor, said that the acquittals “demonstrate once again that law and order is a one-way street; there is no law and order where Black people are involved, especially when they are involved with the police.”

Distrust of Detroit’s judicial system ran so deep, in fact, that local civil rights and Black Power activists decided to call a “People’s Tribunal.” Held at the Central United Church of Christ, beneath a stunning 18-foot mural of a Black Madonna and child painted just months before the uprising, the “People’s Tribunal” brought together hundreds of Detroit’s most militant activists for a mock trial on August 30, 1967.

Amongst the Black lawyers and activists presiding over the case, all of whom would go on to become well-known civil rights and Black Power leaders, was the steely Rosa Parks, midwife to the 1955 Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott.

Parks’ decades-long experience documenting and investigating racialized and sexualized violence in the deep South, and in Detroit, made her a symbolic link between the southern freedom struggle and the burgeoning Black Power Movement in the North. Her presence also reminded everyone that police violence and abusive state power was not only a southern malady, but an American disease that threatened the very essence of democracy, justice and the meanings of citizenship.

Justice was but one of many casualties that week with ramifications that echo to this day. “I lost a son. I lost a son,” Aubrey Pollard Sr. told John Hersey.

There’s a magnitude in the simplicity of his statement. But Pollard Sr.’s losses, like many others, compounded over time. His marriage fell apart and he became separated from his other children. They lost daily interactions with their father.

Mr. Pollard’s oldest son, a soldier serving in Vietnam when the police raided the Algiers Motel, returned from the battlefield to identify his brother at the morgue. The sight of his baby brother in a coffin triggered a nervous breakdown. He recovered slowly at a mental health institution in California. But parts of him were gone forever.

Mrs. Pollard tried to carry on the best she could, but her life, like so many scarred by violence, was forever changed. In a 1967 interview, she focused on her deceased son’s artistic talent, mentioning repeatedly that Aubrey won a prize in elementary school for one of his paintings.

Dreams Destroyed

There is the lost opportunity and wasted talent, an emptiness where the future once cast spells and planted dreams. The families of Carl Cooper and Fred Temple suffered similar fates. What happens to a dream destroyed? To lives torn apart by violence?

David Senak, Ronald August and Robert Paille kept their lives, but lost their jobs and their hopes for a fulfilling future as policemen. What they did that night at the Algiers tormented some of them for a lifetime.

Worse, their acquittals haunted Detroit for decades as unpunished police violence against Black civilians soared in the years after the Algiers, wreaking havoc on the city and her people still reeling from the July 1967 cataclysm.

In that single week, 43 people, including Joseph Chandler — who was shot by David Senak early in the uprising — and the young men at the Algiers Motel, died. Seven thousand individuals, mainly young African-American men, were arrested and nearly 20,000 armed policemen, National Guardsmen, and finally Army paratroopers patrolled the streets.

While police harassment served as the spark that ignited the 1967 riot, there were myriad causes and consequences significantly more dangerous. The story of the Algiers Motel murders captures, in its tragic horror, the often hidden infrastructure of northern racism and white supremacy.

From rabid residential segregation and job discrimination to racialized and sexualized violence to economic and educational disparities and the everyday injustices and biased sentencing in the judicial system, racial inequality and segregation in the “Model City” [a project of President Johnson’s shortlived “War on Poverty” — ed.] was every bit as virulent as it was in the South. Maybe it was even worse.

Detroit still suffers from these past sins. Violence (in all its forms) echoes. Its toll multiplies, mutates and re-emerges in ways that are not always immediately visible, but are undoubtedly clear. The origins of the 1967 riot and its aftermaths have much in common: poverty, lack of decent jobs, crumbling infrastructure, poor educational opportunities, aggressive policing, unequal application of justice and municipal corruption.

July-August 2017, ATC 189