Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

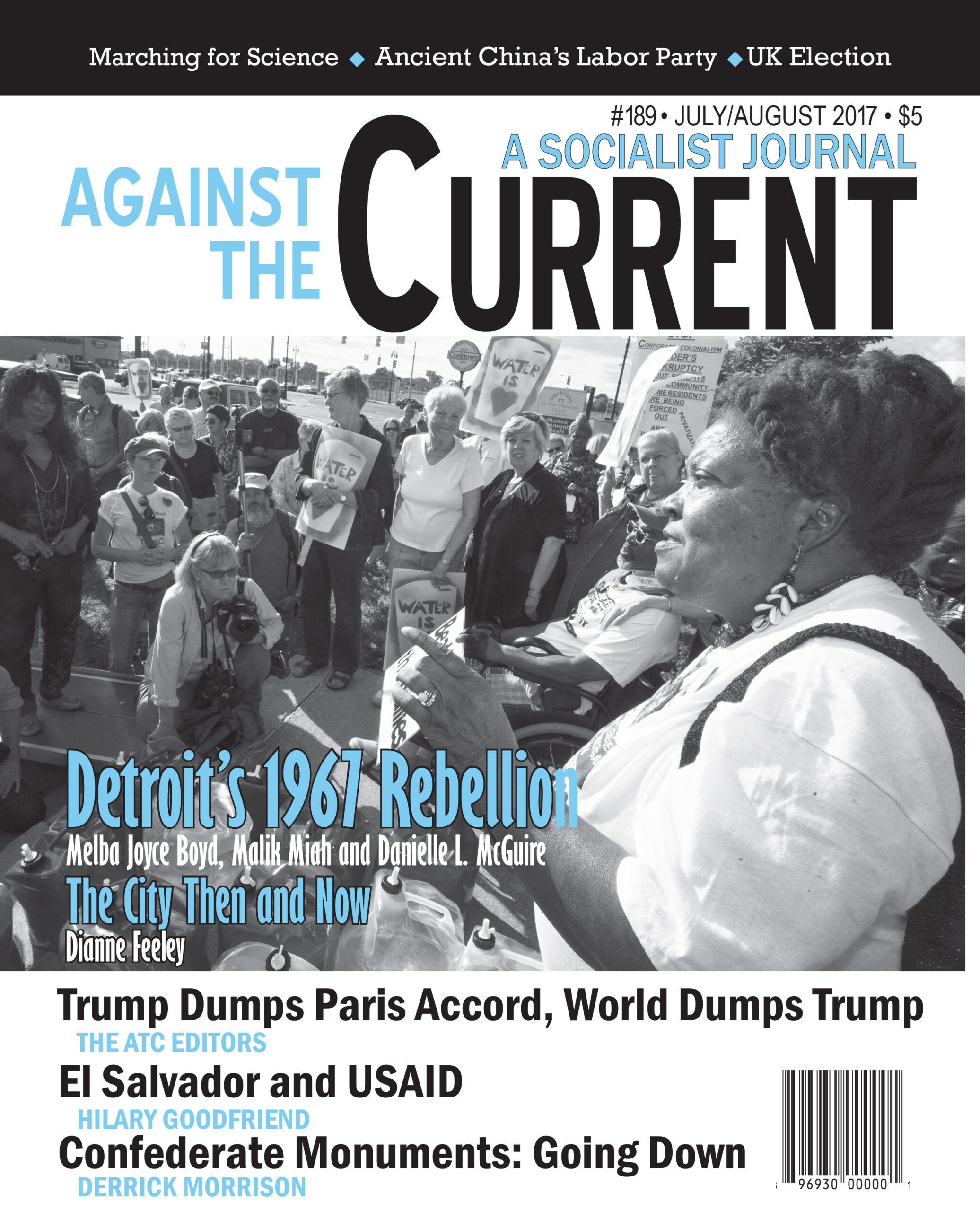

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Derrick Morrison

INTOLERANCE. RACIAL INTOLERANCE. At age 21, Dylann Roof had plenty of it. The symbolic expression of his hatred was the flag of the former Confederate States of America, CSA.

Roof acted out his hatred one night in June, 2015. He killed nine African-Americans worshiping at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. His action set off a swift reaction.

Governor Nikki Haley, a Republican, demanded that the Confederate flag flying on the Capitol grounds in Columbia, the state capital, be taken down. Others like the NAACP had demanded its removal for many years, but never previously the governor.

Both legislative chambers met — the SC Senate and House of Representatives — and after a debate of over 12 hours in the latter chamber, voted the necessary two-thirds majority to enable Haley to take it down. The flag had flown for over half a century, put in place in 1961 by the state government at the time as a defiant gesture to the then rising civil rights movement.

The shock waves set off by the massacre of the nine reverberated across the states that had constituted the Confederacy. Mayor Mitch Landrieu of New Orleans, Louisiana was pushed over the edge. He set in motion the process of removing not a flag, but four Confederate monuments built of granite and metal.

After two tumultuous public sessions where hundreds of people attended and many spoke, the New Orleans City Council voted 6-1 for removal in December of 2015.

Artifacts of What?

Many of us expected action in early 2016. But problems arose. “A contractor involved in the removal work,” writes Janell Ross in the online edition of The Washington Post on May 19 of this year, “pulled out of the job after an arsonist set his $200,000 Lamborghini [automobile] ablaze.”

Pro-Confederate death threats made finding a contractor difficult. Then there were suits filed in state and federal courts by the city’s historic preservationists, calling the monuments “cultural artifacts” and symbols of “heritage.” The local news media sang the same tune.

Are the statues of CSA President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Robert E. Lee “cultural artifacts”? Is a granite obelisk, erected in 1891 and commemorating the brief overthrow of the Reconstruction municipal government in 1874 by the Crescent City White League, part of our “heritage”?

As Mayor Landrieu forcefully stated in his Special Address May 19 while the Lee statue was being taken down, “These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.” [http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2017/05/mayor_landrieu_speech_confeder.html]

To comprehend the confusion of the preservationists and so many others, we need to understand how this “fictional, sanitized Confederacy” — in Landrieu’s words — came about. To do this we have to use as a measuring rod the democratic ideals codified in the 1776 Declaration of Independence and in the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

Both documents were forged in the furnace of social upheaval, and mark the 1st and 2nd North American Revolutions. Or, you could say that the 1863 document was an extension of the 1776 one, which stated boldly: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness….”

Not a few social norms were swept aside in the statement “all Men are created equal.” According to Gordon S. Wood, “In 1777 the future state of Vermont led the way in formally abolishing slavery…. Then in 1780 the Revolutionary government of Pennsylvania, admitting that slavery was ‘disgraceful to any people, and more especially to those who have been contending in the great cause of liberty themselves,’ provided for the gradual emancipation of the state’s slaves….

“In 1783 the Massachusetts Superior Court held that slavery was incompatible with the state’s constitution, particularly with its bill of rights, which declared that ‘all men are born free and equal.’”(1)

After decades of struggle, hesitation, and equivocation, the federal government — while in the midst of the Civil War — finally declared in 1863 that “…all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State…in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforth, and forever free.”(2)

Amendments 13, 14 and 15

The document that unites and applies the principles of 1776 and 1863 is the U.S. Constitution. Produced at a convention in 1787, it opens with: “WE THE PEOPLE of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

It ends with, “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of government….”

To implement the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were added to the Constitution. The 13th declared, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude…shall exist within the United States….”

The 14th resolved, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The 15th simply asserted, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This concerned only the freedmen since women did not have the right to vote until passage of the 19th Amendment.

Reconstruction Aborted

These were federal statutes, to be enforced by federal, state and local governments. To reorganize the former states in rebellion, the U.S. Congress set up Reconstruction governments. The freedpeople and white supporters of the new situation participated, backed by the presence of the U.S. Army. Pro-Confederate groups prone to violence were suppressed — for a while.

Starting with General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Field Order Number 15, issued in January of 1865, there were pilot projects at landowning for the freedmen. Sherman’s Field Order concerned the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina. The Freedmen’s Bureau, organized by the Feds, also initiated some projects.

But the big railroads, banks, and other industrial companies that controlled the Republican Party were not really up to the task of breaking up the plantations and putting into effect a land redistribution program for the freedpeople and landless whites. Some of the plantations were auctioned off, meaning that only big moneyed individuals from the North could play the game.

The Republican economic program for the freedpeople, to enable them to make the transition from slave labor to free labor, was shattered by the economic crash of 1873. Spawned by the collapse of overextended credit due to the overexpansion of the railroads for a market that couldn’t digest it, the depression lasted five years and was worldwide in scope.

The Reconstruction experiment was removed from the table, as the industrial titans wanted “peace” in the South. The eventual withdrawal of the U.S. Army from the region gave the green light to pro-Confederate forces like the Ku Klux Klan.

This signaled the end of federal enforcement of the 14th and 15th Amendments. Citizenship rights and the right to vote for African Americans in the South were crushed.

Fake History vs. Civil Rights

In this era, the opening of Jim Crow segregation, began the systematic falsification and rewriting of the history of the Civil War and the Confederacy. Pro-Confederate statues and monuments started going up after 1880, after the Reconstruction governments were overthrown. In New Orleans: Lee in 1884, the obelisk in 1891, Davis in 1911, and Beauregard in 1915.

For the rewriters, the Civil War became a “misunderstanding” (as Donald Trump echoes today) and Confederate generals and politicians were transformed into great Southern heroes and cultural icons. African-Americans were routinely humiliated, brutalized, and mutilated.

Mayor Landrieu, in his Special Address, estimates “nearly 4,000 of our fellow citizens were lynched, 540 alone in Louisiana….” Lynching Black people became a sport in the South. Postcards were sent out showing smiling white faces in the foreground and a charred African-American body in the background. What Landrieu calls the “false narrative” became commonplace.

In today’s German Republic, the places where victims of Hitler and Nazism were seized are memorialized with a plaque in the pavement. When the social justice movement in the United States is stronger, we might use that as one way to remember those who were lynched.

The labor uprising in the 1930s that saw the formation of local unions and the national Congress of Industrial Organizations, along with the post-World War II anti-colonial revolution that swept Africa, Asia and Latin America, set the stage and inspired the rise of the anti-segregation struggle in the United States in the 1950s.

During one month alone in 1954, the Vietnamese people defeated their French colonizers at the impregnable fortress of Dienbienphu on May 7, and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the demand for school desegregation in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas on May 17.

The Jim Crow legal edifice came crashing down with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The former signaled Federal government enforcement in the South of the 14th Amendment, the latter enforcement of the 15th and 19th Amendments.

With reacquisition of these rights it was a matter of time before these pro-Confederate monuments would collide with the new political and social realities. Mayor Mitch Landrieu became the instrument of history to correct this imbalance in New Orleans. The struggle continues to remove other statues and street names that symbolize white supremacy (see the Facebook page of Take ’Em Down NOLA, https://www.facebook.com/TakeEmDownNOLA/ —ed.).

The long fight to remove pro-Confederate monuments reaffirms the words of the U.S. Constitution, expands the boundaries of democracy, and ultimately is a fight for a democracy and a republic where discrimination because of race, gender, sexual orientation, religious belief or national origin does not exist.

Out of that fight, of course, would emerge a type of new type of democracy, a new type of republic.

That’s the long view of history.

Notes

- Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty, A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Oxford University Press, Inc., 2009), 519-520.

back to text - Geoffrey C. Ward with Ric Burns and Ken Burns, The Civil War, An Illustrated History (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1990), 166.

back to text

July-August 2017, ATC 189