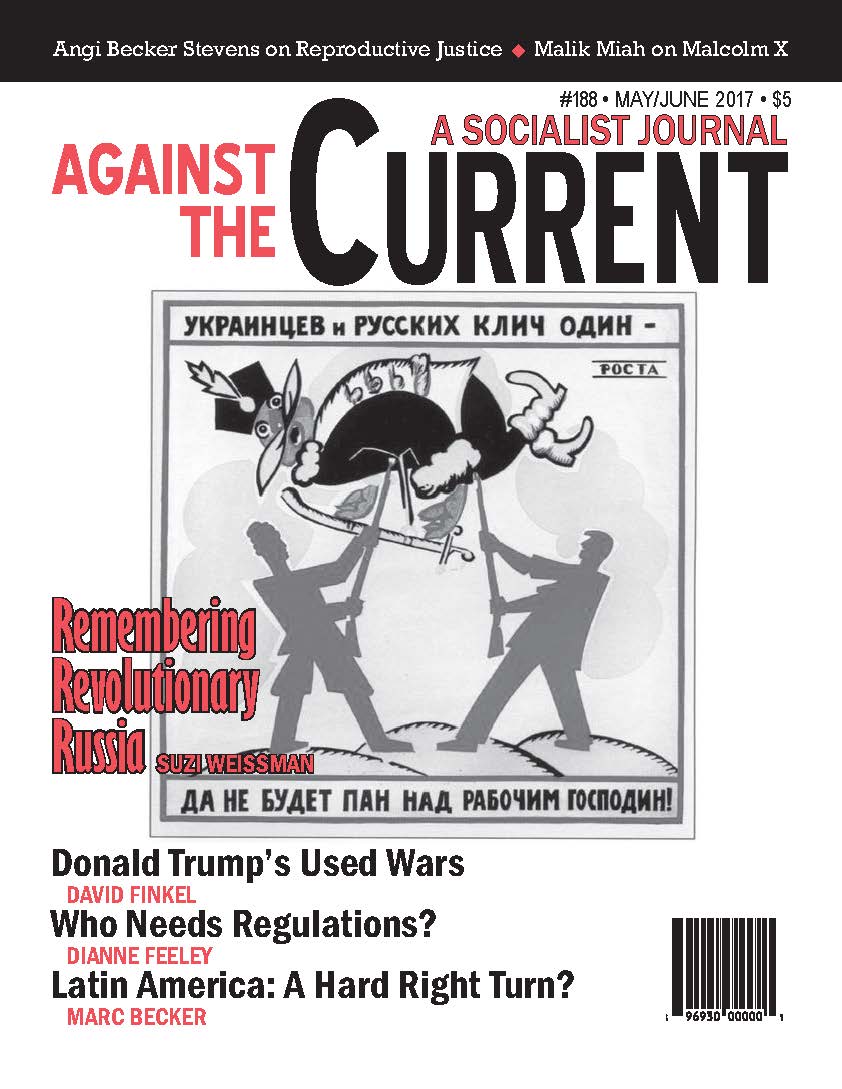

Against the Current, No. 188, May/June 2017

-

What Kind of Opposition?

— The Editors -

Learn from Malcolm X

— Malik Miah -

Trump and the Middle East

— David Finkel -

Regulation -- Who Needs It?

— Dianne Feeley - Rasmea Odeh Accepts Plea Agreement

-

What is Reproductive Justice?

— Angi Becker Stevens - A Note on Terms

-

Latin America: A Conservative Restoration?

— Marc Becker -

Science for the People with the EZLN

— John Vandermeer and Ivette Perfecto -

The Russian Revolution and Workers Democracy

— Suzi Weissman -

Baba Jan, Pakistani Prisoner

— Farooq Tariq -

Time has long passed that you could rob the fattest bank in america

— Kim D. Hunter - Reviews

-

Franz Kafka: In His Times and Ours

— Alan Wald -

C.L.R. James and His Times

— Anthony Bogues -

E.P. Thompson's Socialist Humanism

— Dan Johnson -

Detroit Radicals' Odyssey

— Bill V. Mullen -

Race and the Real California

— Seonghee Lim -

Market Uber Alles

— Kim D. Hunter -

Leonard Weinglass in History

— Matthew Clark - In Memoriam

-

Reflections on Tom Hayden

— Howard Brick -

Seymour Kramer (1946-2017)

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Remembering a Friend

— Mike Davis -

Regina Pyrko McNulty (1923-2016)

— Dianne Feeley

Dan Johnson

E.P. Thompson and the Making of the New Left:

Essays & Polemics

Edited by Cal Winslow

Monthly Review Press, 2014, 288 pages, $23 paper.

THE ENGLISH WORKING class “did not rise like the sun at an appointed time. It was present at its own making.” In frequently quoted lines from the preface to The Making of the English Working Class (1780-1832), E.P. Thompson endeavored to “rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver, the ‘utopian’ artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity.”

More broadly, Thompson sought to elucidate class as a historical phenomenon that involved changing human relationships over time, rather than being a static structure or simple category of analysis.

Published in 1963, The Making had a profound influence on countless young leftists, transforming scholarship with a new methodology: “history from below.” The book’s explicit critique of sociological abstractions and structural interpretations of social relations challenged contemporary academic fashion, and Thompson’s emphasis on human agency, popular politics and the common struggles of working people reoriented a traditional focus on institutions and elites — even within labor history circles.

While The Making remains his most celebrated work, Thompson’s eclectic body of work includes biographies of literary figures like William Morris and William Blake; pioneering studies of crime, food riots, and industrialization in 18th-century England; and political-theoretical works, most famously a ferocious polemic in The Poverty of Theory against the philosophical obscurantism of the French philosopher Louis Althusser and his followers.

Thompson’s writings as an activist and public intellectual between 1956 and 1962 are the focus of the recent Monthly Review Press collection E.P. Thompson and the Making of the New Left: Essays & Polemics (hereafter EP), edited by his former student Cal Winslow.

Many of the virtues — and it must be said, vices — Thompson is famous for are on display in this collection of relatively obscure works. Here, as in much of Thompson’s writing, occasional lapses into long-windedness and moralizing self-righteousness are more than compensated for by a fiery, impassioned and powerful literary style.

The essays provide a fascinating look into the historian’s pre-Making intellectual development, starting with “Through the Smoke of Budapest,” written in the wake of the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, and ending with “The Free-Born Englishman” in 1962, a New Left Review article that would be a crucial chapter in The Making.

For readers already familiar with his work the collection will contextualize many of Thompson’s lifelong concerns, in particular his interest in the relationships among human agency, social change, and popular politics and culture. For activists not familiar with Thompson, most relevant will likely be the historian’s commitment to socialist humanism, a concept that links the otherwise diverse essays on history, politics, theory and criticism.

The New Left and Socialist Humanism

As is evident in the book’s subtitle, Thompson was a leading figure in the “first” New Left in Britain in the 1950s and early 1960s. As Winslow points out in a valuable introduction, the New Left was born in 1956, a year that began with Nikita Khruschev’s “secret speech” to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which denounced the crimes of Stalin and was quickly leaked to the West.

Before the year was over a British, French, and Israeli imperialist plot to seize the recently nationalized Suez Canal from Gamal Abdel Nasser was thwarted, and a workers’ rebellion in the Hungarian capital of Budapest was crushed by Soviet tanks.

In Britain and the United States, the period following World War II was a time of relative economic prosperity and centrist political consensus. For liberal intellectuals, “affluence” in the capitalist West signaled the “end of ideology,” sociologist Daniel Bell’s term for the supposed irrelevance of ideological politics in the postwar age.

The New Left was a direct challenge to a dominant liberal order that fostered mass apathy and complacency, and was led in Britain by Thompson, Doris Lessing, Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams.

Though Winslow doesn’t engage in comparison, the U.S. and British New Lefts differed in important ways. Perhaps most notably, some in the United States (for example C. Wright Mills and Herbert Marcuse) claimed that in the affluent West the working class was no longer an agent of revolutionary change; Thompson and others in the UK disagreed.

New Lefts on both sides of the Atlantic were born of a double rejection however: of an unquestioning Old Left conformism to an organizational model based on the Party and Soviet orthodoxy; and of a postwar capitalist system whose most prominent features were mindless consumerism and a milquetoast political order masquerading as democracy.

The New Left, by contrast, was a movement from below that, as Winslow puts it, was “decentralized, non-hierarchical, creative, experimental, and humanist.” For Thompson, whose essay “The New Left” first appeared in The New Reasoner in 1959 and is reprinted in EP, the 1950s was “the decade of the Great Apathy,” reflecting a profound sense of impotence in the face of forces seemingly beyond the individual’s control.

For Thompson the New Left’s mission was to build bridges between intellectuals and the working class through the construction of an alternative cultural apparatus. It would be a movement to push socialist theory outside the confines of academia to popular journals, clubs, novels, cafes, workshops, cooperatives, and — most importantly — to a revitalized labor movement.

In 1957, following their resignation from the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) over its support of the Soviet invasion of Hungary, Thompson and fellow labor historian John Saville launched The New Reasoner. The journal’s first issue contained Thompson’s “Socialist Humanism: An Epistle to the Philistines,” also reprinted in EP.

Although “Socialist Humanism” focused most of its polemical ire against Stalinism, the essay also called for a return to the humanism, and even morality, of Marx and Engels. References to Shakespeare (specifically how Marx was inspired by Timon of Athens) and William Blake foreshadow how Thompson would later integrate literature and social history while also attempting to formulate a reinvigorated humanist socialism.

In Thompson’s view the humanism of Marx and Engels had been bastardized among much of the left by an economic determinism that ultimately produced contempt for the people among a self-proclaimed revolutionary vanguard.

Marxist interest in humanism and the concept of alienation can be traced to philosophers Georg Lukács and Antonio Gramsci in the 1920s and 1930s. British intellectuals’ concerns with alienation and the humanism of Marx’s early writings in the 1950s were paralleled in the United States in the works of C.L.R. James, Raya Dunayevskaya, and Grace Lee Boggs.

As historians, James and Thompson shared a concern with process and human agency; James’ Black Jacobins (first published in 1938) and Thompson’s The Making arguably stand as the two most important works of people’s history in the 20th century.

Thompson’s version of socialist humanism — more a tradition of thought than a coherent theory — was unique in its insistence on going beyond a traditional focus on economic equality.

While a truly socialist society would radically transform economic relationships in favor of an egalitarian system based on need rather than profit, it also required a revolution in human relationships, as Thompson tirelessly argued. The insertion of a moral position into socialist theory and practice was therefore essential.

In “The Communism of William Morris” Thompson claimed: “Economic relationships are at the same time moral relationships; relations of production are at the same time relations between people, of oppression or of co-operation; and there is a moral logic as well as an economic logic, which derives from these relationships. The history of the class struggle is at the same time the history of human morality.”

While Thompson’s moral critique at times seem overwrought today, his assertion in “Socialist Humanism” that economic changes were felt by individuals and classes in “the human consciousness, including the moral consciousness” was an important corrective to contemporary doctrine among much of the left.

Disappearance and Return

The influence of socialist humanist ideas among much of the left waned as the war in Vietnam increasingly preoccupied radical intellectuals and an emerging youth movement in the 1960s. As Barbara Epstein argues in “On the Disappearance of Socialist Humanism,” the left’s growing focus on the war, and hostility to American imperialism more generally, replaced the notions of peaceful coexistence and opposition to the arms race — central issues for socialist humanists, as evidenced in Thompson’s case in his involvement in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

New social movements like Black Power and feminism emerged along with a Third Worldist approach to revolutionary transformation heavily influenced by Mao and other anti-colonial revolutionaries, most notably Che Guevara. Many of these movements challenged the Western Enlightenment tradition as Eurocentric, racist and sexist.

Socialist humanists’ general commitment to Enlightenment ideals like reason and freedom of thought appeared to some young radicals as complicit with liberalism or, worse, little more than a traditional bourgeois individualism with a human face.

With liberalism increasingly viewed as the primary political and ideological enemy in the days of the Cold War consensus of the 1960s (the right’s coming resurgence was largely unforeseen), socialist humanist ideas gave way to anti-imperialism and the prospect of revolution in the Third World. Corresponding to these changes, among much of the Western intelligentsia the rise of explicitly anti-humanist theories became increasingly popular on college campuses.

Although influential ideas critical of humanism could be found in Nietzsche, Freud and Martin Heidegger, none of these thinkers could be considered remotely sympathetic to socialism or the left, despite many theorists’ (continuing) attempts to appropriate them. The French philosopher Louis Althusser, however, brought a new Marxist perspective to a critique of humanism and what he disdainfully referred to as historicism and empiricism in Marxist thought in the 1960s.

As a historian and self-described socialist humanist in the Marxist tradition, Thompson unsurprisingly took umbrage with Althusserian structuralism. His Poverty of Theory, a play on Marx’s Poverty of Philosophy and published in 1978, mercilessly pilloried Athusser’s interpretation of Marx and his theory of knowledge, or epistemology.

Without going into the details of — to put it charitably — the expansive argument, ultimately the most important point for Thompson was that the practical relevance, and danger, of Althusserian structuralism was its profoundly damaging impact on intellectual discourse among the international left. This kind of Marxism’s divorce from the real world of experience and historical change continually reproduced an elitist division between theory and practice. In Thompson’s view the consequences for leftist politics could only be inertia and a retreat into sterile ivory tower debates.

If the popularity of Althusser and his students was relatively short-lived, a more lasting challenge to humanism — and by extension Marxist/socialist humanism — has been the rise of poststructuralist and postmodernist theories. Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, many intellectuals adopted postmodernist methods of criticism that privileged fluid and multiple identities over a politics rooted in social and economic inequality.

While war was being waged against the working classes in Reagan’s America and Thatcher’s Britain, in academia the utility of the concept of class itself came to be questioned. Class came to be seen as an identity, rather than a social relation, with little claim to privilege over any other identity.

One irony of these intellectual shifts is that Thompson’s work has been simultaneously criticized by postmodernists for being too rooted in an “Old Left” concern with capitalism and class, and by some Marxists for being preoccupied with “culturalist,” relativist interpretations of class rather than objective social conditions.

The sheer volume of literature criticizing and defending Thompson, which borders on a separate academic industry, testifies to his enormous influence. What the EP collection demonstrates is that, like his scholarly work, Thompson’s political writing remains deeply relevant today.

Despite the pernicious impacts of neoliberalism so glaringly evident since 2008, the left’s need to combat alienation and apathy among large segments of the population remains a major challenge. As in the postwar era in which Thompson wrote, apathy and disillusionment work to the advantage of conservatism and reaction, as seen with the rise of right-wing populist parties and groups throughout the world in recent decades.

The Hope

In “Where Are We Now?” Thompson argued for the conceivability that the salaried, professional and wage-working classes would discover a common sense of identity “as against isolated centers of financial power and ‘vested interest.’” His claim in 1960 that “democratic revolutionary strategy, which draws into a common strand wage demands and ethical demands, the attack on capitalist finance and the attack on the mass media, is the immediate task,” clearly resonates today.

As if in response to a dominant anarchist tendency among much of the left in recent decades, Thompson argued in “Revolution” that socialists need to formulate “an offensive campaign to place the transition to the new society at the head of the agenda.”

Few strategic demands could be more pertinent at a time when widespread popular hostility to entrenched interests — whether in the form of Brexit or in the election of Donald Trump — has been appropriated by the right.

Although opposition to neoliberal capitalism has replaced criticism of Cold War conformity as the primary objective of leftist thought and strategy, the socialist humanism of Thompson and others of the New Left reminds activists of the need to listen to the voices of those most exploited by the system.

Perhaps Thompson’s most endearing virtue, clearly evident in EP and essential for the formation of a revolutionary socialist alternative in the 21st century, was his infinite curiosity, as he frequently repeated, in “real men and women.”

As the intellectual hegemony of postmodern and poststructuralist thought recedes, revisiting the popular struggles of ordinary people through a socialist humanist framework offers useful lessons for the study of the past as well as for the battles waged in the present.

People lead lives, interesting and noble lives, even under capitalism in the 21st century. And if we forget that, Thompson would surely have argued, we have no business calling ourselves socialists in the first place.

May-June 2017, ATC 188