Against the Current, No. 187, March/April 2017

-

Trump's Road to Ruin

— The Editors -

Making Trump's America Ungovernable

— Malik Miah -

The Ohio Vote in November

— Kim Moody -

Sanders' Campaign & the Democratic Party

— Jules Greenstein -

Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality

— Christopher Vials -

A Partial Peace in Colombia

— Kevin Young -

Lessons from New Orleans

— Peter Brogan interviews Kristen Buras - Women in Struggle

-

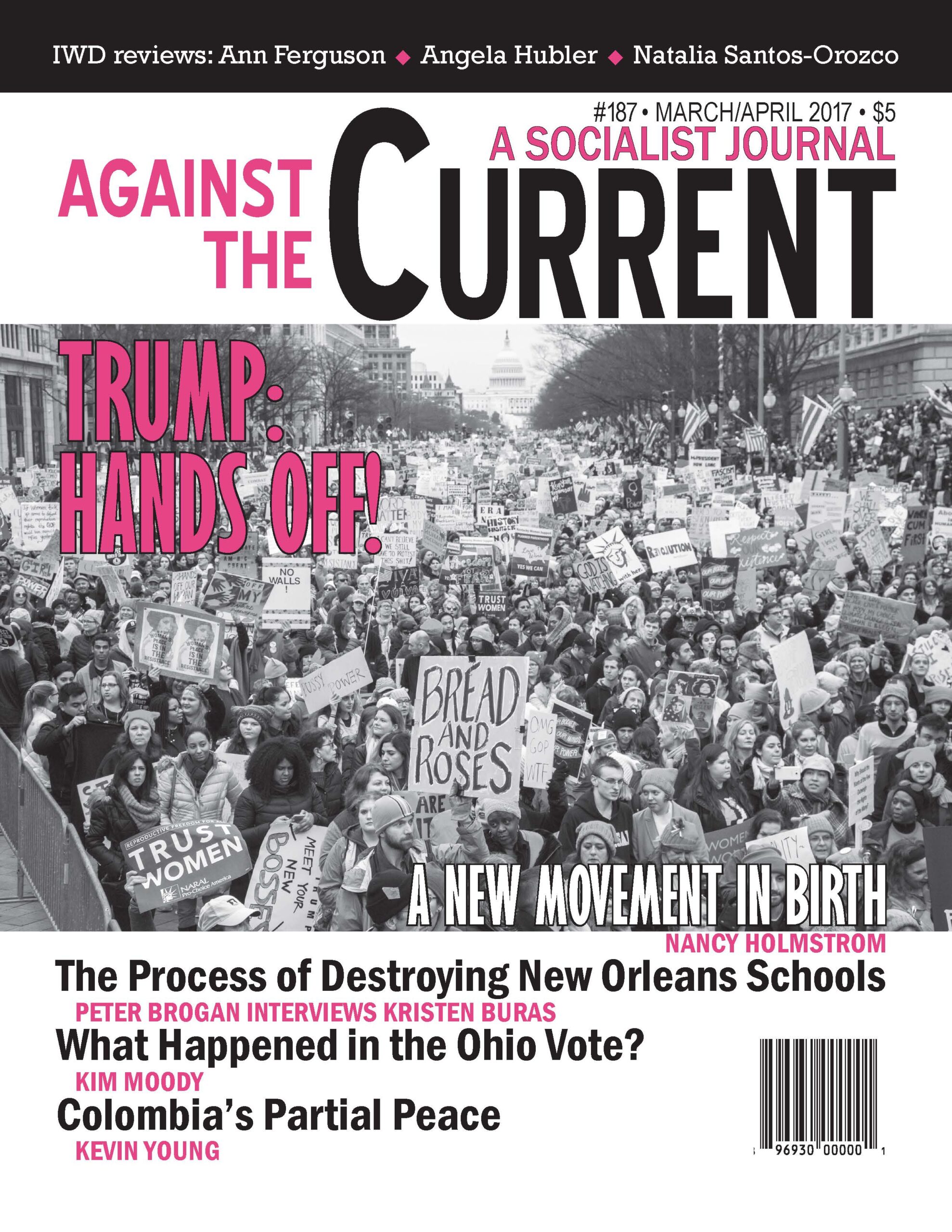

Birth of a New Movement

— Nancy Holmstrom -

The Journeys of Julia de Burgos

— Natalia Santos-Orozco -

Florynce Kennedy & Black Feminism

— Angela Hubler -

Marxist and Feminist Interventions

— Ann Ferguson -

Beyond Lean-In: For a Feminism of the 99% and a Militant International Strike on March 8

— Linda Martin Alcoff, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Angela Davis, Nancy Fraser, Rasmea Yousef Odeh, Barbara Ransby & Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor - Reviews

-

Demythifying Native Americans

— Robert Caldwell -

Attica: The Revolt and Afterward

— Jack M. Bloom -

Arab Spring: Against Shallow Optimism and Pessimism

— Atef Said -

A Global Matrix of Control

— Michael J. Friedman -

The Politics of Some Bodies

— Peter Drucker - In Memoriam

-

Erwin Baur (1915-2016)

— Charles Williams -

Lillian Pollak

— Dianne Feeley

Dianne Feeley

ACTIVIST, REVOLUTIONARY SOCIALIST and writer Lillian Pollak died in New York City at the age of 101. Her autobiographical novel, The Sweetest Dream, began with the Russian Revolution and ended with the death of Leon Trotsky in Mexico.

Self-published in 1998, when she was 93, the book chronicled the lives of two friends who grew up in New York City, flourished during the radicalization of the 1930s but chose different political trajectories. Her friend remained in the Communist Party, while Lillian, much more of a free thinker, joined the Trotskyist movement. (See Alan Wald’s review, “Reviewing Red: Love and Revolution,” ATC 140, May-June 2009, http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/2168).

Lillian grew up in an impoverished and difficult home in upper Manhattan, the youngest of three sisters. Bertha, at age 20, was killed in an automobile accident. Her sister, Barbara, belonged to the same revolutionary organization that Lillian joined.

Although she never mastered Pittman shorthand, Lillian snagged a secretarial job for the Works Project Administration’s Federal Arts Project. There she met young artists of the period including Jackson Pollock and Martha Graham. This met with her desire to broaden her horizon, and cultural happenings remained an important part of her life.

As a young revolutionary, she traveled to Mexico and met Leon Trotsky and Natalia Sedova. She confessed she found Trotsky a bit cold — she was a more outgoing person who enjoyed repartee.

Lillian was particularly drawn to the Trotskyist leader Max Shachtman, recalling decades later how he could hold an audience even when the lights went out in the meeting hall. Following Stalin’s 1939 pact with Hitler and then the Soviet invasion of Poland and Finland, Shachtman concluded that the Soviet state under Stalin was no longer worthy of “unconditional defense” and broke with Trotsky.

Usually under the impact of such events, many revolutionaries didn’t remain revolutionary activists. That was true of Lillian, who had recently married revolutionary activist Eddie Pollak; the following year their son Richard was born. Two years later the Pollaks had a daughter, Robbie (Roberta).

While attending night school at Hunter College, Lillian continued to work and provide a comfortable environment for her growing family. It took her 10 years to graduate, but always a striver, she graduated cum laude.

When Robbie was five, the Pollaks were told she had Wilms’ tumor, a fatal illness. They searched for possible cures and were devastated by her death. The next few years seemed dark: The family moved to California, Lillian suffered a miscarriage, and then returned to New York when Eddie was unable to find steady work. In 1950 Nancy was born.

When the United Federation of Teachers was formed in March 1960, Lillian signed up. That November the union went out on strike for recognition and although she was the only striker out of the 60 teachers at her school, she was the solo picketer at her school. The following year the UFT became the collective bargaining organization for all New York City teachers.

But, in 1968, when the union opposed community control of Black and Puerto Rican community schools, Lillian picketed the central office where Shachtman’s wife, Yetta Barshevsky, was administrative assistant to UFT president Albert Shanker. (Known as Yetta Bara, she was the author of Shanker’s weekly columns.) So when Lillian picketed the office, she made sure to point her finger at Yetta, telling her she should be on that picket line and not part of the bureaucracy.

Teaching in NYC public schools, she received, and saved, letters from students expressing their appreciation for her years after her retirement. By the time she retired, she had a Master’s degree and counseling certificate. Interested in film studies, she became an adjunct at Queens College and attended far-flung film festivals. She taught and counseled at a Jewish summer camp into her nineties, explaining that she kept on working because her cat enjoyed the camp.

Her husband became a salesman for a liquor distributor, organized a union, founded the Astoria-Long Island City NAACP and was active during the Vietnam War in the Western Queens Committee to end the War. He joined the Socialist Workers Party in the late 1950s and remained a member until his death in 1984.

Shortly after his death Lillian decided to move to Manhattan so she would be able to participate more fully in political activity. She joined a socialist organization again, but found it constraining.

She traveled, wrote poetry, followed the news, composed songs for the Raging Grannies, attended lectures at the Brecht Forum and Center for Marxist Education, supported Palestinian rights and participated in demonstrations large and small.

Just a few months before her death following a stroke she was delighted to read her poem about Israel’s war on Gaza, hoping it would open people’s eyes to the situation Palestinians face under occupation. (See the You Tube video, “Cousin, Do Not Come: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UvJlOwf8Tg0.) Politically active even as she found it more difficult to stand and march, Lillian solved the problem by asking her good friend Corinne Willinger to drive, and brought along her compact stool.

Fiercely committed to social justice throughout her long life, Lillian followed the lives of her children, particularly delighting in her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. At her memorial meeting in November 2016, many spoke of how she always had time to prepare lunch or plan how to make a bigger impact in opposing war or supporting political prisoners.

March-April 2017, ATC 187