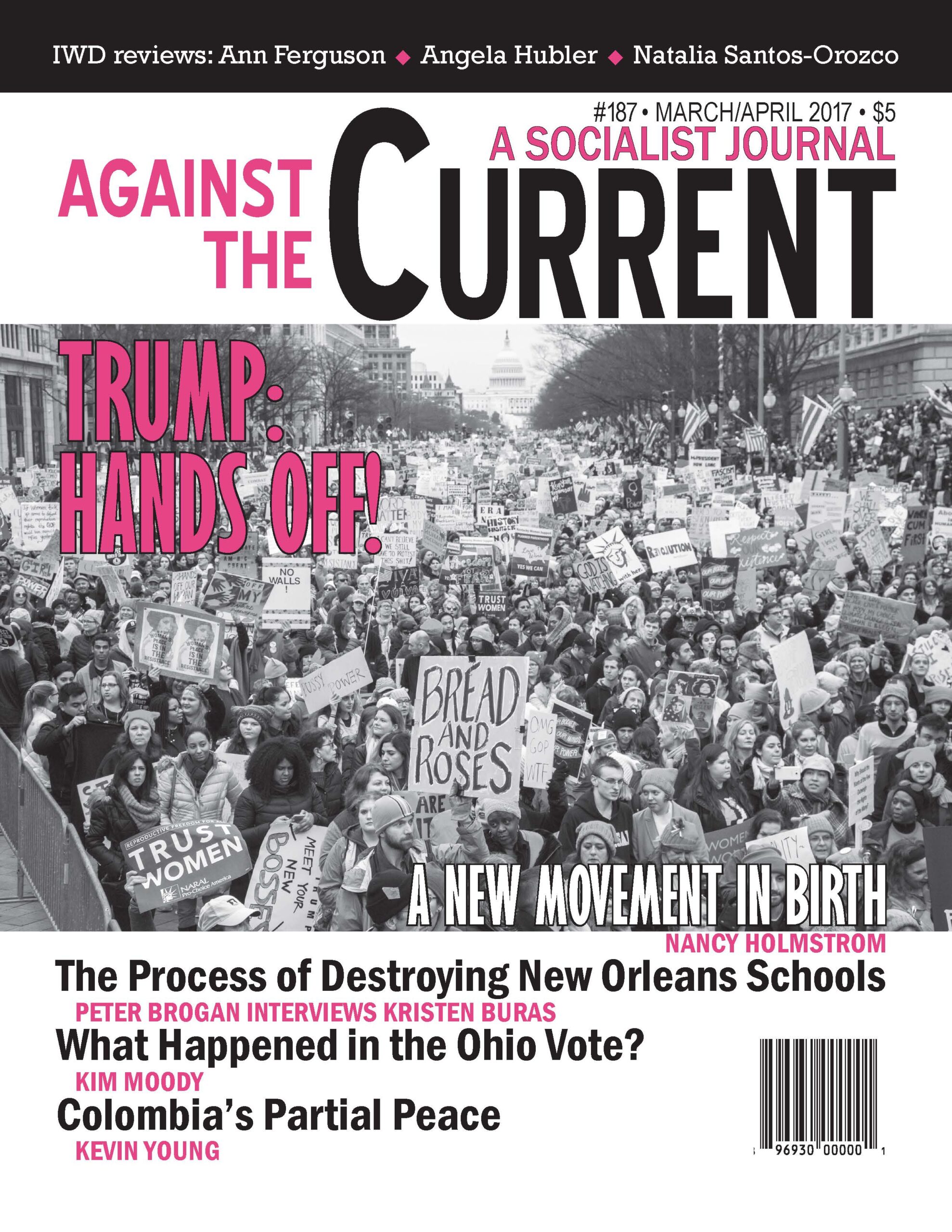

Against the Current, No. 187, March/April 2017

-

Trump's Road to Ruin

— The Editors -

Making Trump's America Ungovernable

— Malik Miah -

The Ohio Vote in November

— Kim Moody -

Sanders' Campaign & the Democratic Party

— Jules Greenstein -

Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality

— Christopher Vials -

A Partial Peace in Colombia

— Kevin Young -

Lessons from New Orleans

— Peter Brogan interviews Kristen Buras - Women in Struggle

-

Birth of a New Movement

— Nancy Holmstrom -

The Journeys of Julia de Burgos

— Natalia Santos-Orozco -

Florynce Kennedy & Black Feminism

— Angela Hubler -

Marxist and Feminist Interventions

— Ann Ferguson -

Beyond Lean-In: For a Feminism of the 99% and a Militant International Strike on March 8

— Linda Martin Alcoff, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Angela Davis, Nancy Fraser, Rasmea Yousef Odeh, Barbara Ransby & Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor - Reviews

-

Demythifying Native Americans

— Robert Caldwell -

Attica: The Revolt and Afterward

— Jack M. Bloom -

Arab Spring: Against Shallow Optimism and Pessimism

— Atef Said -

A Global Matrix of Control

— Michael J. Friedman -

The Politics of Some Bodies

— Peter Drucker - In Memoriam

-

Erwin Baur (1915-2016)

— Charles Williams -

Lillian Pollak

— Dianne Feeley

Atef Said

Morbid Symptoms:

Relapse in the Arab Uprising

By Gilbert Achcar

Stanford University Press, 2016, 240 pages, $21.95 paperback.

Workers and Thieves:

Labor Movements and Popular Uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt

By Joel Beinin

Stanford University Press, 2015, 176 pages, $12.99 paperback.

IN 2011, MILLIONS in the Middle East and around the world rejoiced over the Arab Spring uprisings. By 2013, however, most were disappointed at the apparent major defeat of these uprisings.

What went wrong? People had moved from extreme optimism to extreme pessimism. Was the problem in the actual events that happened, or in people’s perception of these events? Will getting the story right help us navigate the way between (shallow) optimism and (shallow) pessimism?

Grasping the multifaceted complexity of the story will not only shield us from superficial political emotions, but will also provide us with the right lessons for future conflicts. Morbid Symptoms, by Gilbert Achcar, and Workers and Thieves, by Joel Beinin, are good exemplars of critical analyses that aim to get the story right.

A conventional narrative is that the Arab Spring uprisings started with a street vendor in Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, setting himself on fire in December 2010. Shortly after his death three weeks later, peaceful protests erupted, led by some educated and middle class youth carrying iPhones who protested and occupied squares.

Many Western scholars of Middle East politics were shocked at the onset of the protests, as they had not foreseen the uprisings coming in the Arab World. Immersed in Orientalist thinking and rigid paradigms about authoritarianism in the region, they had overlooked populations and movements. These experts then started to impose ready-made paradigms about democratization and transitions to democracy.

When things did not go well, most reverted to their favorite explanation: the persistence of “authoritarianism.” For the most part, no adequate attention was given to the social and economic factors in the making of the uprising, and the shaping of their outcome. In particular, the role of labor strikes was largely absent from most analyses.

Those scholars who dared to discuss international and regional dimensions of the Arab Spring did so in simplistic terms, involving intervention or lack thereof, with “intervention” meaning strictly military. There was no real discussion of the Western powers’ efforts to contain the uprisings, or the regional powers’ counter-revolutionary work.

With the account of the uprisings reduced to the role of political elites and the perseverance of authoritarianism and authoritarian culture in the region, the complex internal story was missing and the international story mostly ignored.

The uprisings may be defeated, for now, and things have gotten much worse. Yes, we have the right, not unlike these Western liberal scholars, to be deeply disappointed about what happened in the region.

My argument, however, is that getting the story right is the most important task both for critical scholars and for activists, especially in the context of the present difficult times, global counterrevolutions, and the rise of fascism.

It is most naïve to see only one oversimplified, gloomy side of the picture. Underneath there exists a global crisis of neoliberalism and the rise of leftist and radical sentiments and anger from the millennial generations, even as these seem to be currently defeated. As well, working class strikes never stopped in the Middle East.

Understanding these complexities is essential for a better appreciation of the present political tension. In this review, I will discuss key ideas in each book, starting with Achcar’s, followed by addressing some commonalities and concluding questions and thoughts.

Morbid Symptoms

Gilbert Achcar’s book opens with two epigraphs. One is a famous quote from Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born: in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

As Achcar indicates in the introduction, this book was initially written as a short assessment to be added to a new edition of his first book on the Arab Spring, The People Want (reviewed previously in ATC, online at https://www.solidarity-us.org/node/4166).

His intended update, however, grew longer than expected. It can be read both as an extension of the old book, and as a stand-alone new work.

The book is divided into two main chapters, one on Syria titled “The Clash of Barbarisms,” and another on Egypt called “The 23 July of Abdul-Fattah al-Sisi,” in addition to an introduction and conclusion.

In the introduction Achcar lays out his theoretical approach and offers two important critiques of mainstream analyses on the Arab Spring grounded in the paradigms of Western academia.

One critical factor that Achcar affirms was the structures of most Arab states on the eve of the Arab Spring, as either “plainly patrimonial” (the eight Arab monarchies plus Libya and Syria) or “neopatrimonial.”

A patrimonial state, in simple terms, is one where government is centered around one leader. In these states there was a corrupt trilaterial “power elite,” meaning “a ‘triangle of power’ constituted by the interlocking pinnacles of the military apparatus, the political institutions and a politically determined capitalist class (a state bourgeoisie).” (7)

Thus it was “perfectly deluded” in the first place to assume that the uprisings would go through a relatively smooth process as, for example, in Eastern Europe. Rather, as Achcar had proposed in his earlier work, the uprisings were only the onset of “a long-term revolutionary process.”

Second, Achcar also proposes an important formula to understand what happened in the region: one revolution vs. two counter-revolutions. Achcar proposes that we should think of counterrevolution not narrowly as the forces of the old regime, but also as including “the reactionary alternative to the reactionary order.”

He specifically notes the role of the Saudi Kingdom and the Emirate of Qatar and the “Islamic Republic” of Iran, which “all compete in supporting various brands of movements covering the full spectrum of Islamic fundamentalism, from conservative Salafism and the Muslim Brotherhood to Khomeinism and fanatical ‘Jihadism.’” (8)

Achcar distances himself from some naïve leftist analyses, which propose that the Muslim Brotherhood has been a reactionary but not a counter-revolutionary force.

These are two crucial analytical moves. With respect to the states and the old regime, it was very naïve to study the states as simple coherent entities, and ignore the infrastructure of the states and the old regime. With respect to counterrevolution, it is likewise naïve to limit this to the old regime (which itself was not simple); instead, one should broaden the analysis to think of societal and regional forces.

Egypt: Al-Sisi’s Coup

Achcar starts the Egypt chapter with a very relevant comparison between the rise of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and his coup d’etat on 2 December 1851 in France and the rise of Abdul Fattah al-Sisi in Egypt and his coup in Egypt of 3 July 2013.

Some supporters of al-Sisi as well as the state used some nationalist propaganda and invoked the image of Gamal Abdel-Nasser and his coup in 1952 in Egypt, suggesting that Sisi is a new Nasser. Despite the useful comparison, Achcar was also careful not to ignore the specificities of these cases.

Of course, 23 July is the date of the coup that Egypt’s Free Officers, led by Gamal Abdel-Nasser, executed in 1952, overthrowing the Egyptian Monarchy. On 3 July 2013, Abdul-Fattah al-Sisi led a coup toppling Mohamed Morsi, and ending the short-lived Egyptian Second Republic (2011-2013).

Without any fear of ridicule, Sisi’s coup was travestied ad nauseam by its enthusiasts as a second iteration of what, in Egypt, is referred to as the “23 July Revolution.” The truth, however, is that Louis Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup had much more in common with his uncle’s — they were both essentially reformist coups, ending a phase of revolutionary turmoil in order to carry through a major stage of France’s bourgeois transformation — than Abdul-Fattah al-Sisi’s coup has with the one led by Nasser. The latter was a textbook case of a revolutionary coup d’état, whereas the coup executed on 3 July 2013 was definitely a reactionary one that restored Egypt’s old regime — indeed, with a vengeance. (65-66, Achcar’s emphasis)

Before analyzing the Egyptian coup, Achcar traces the story back to the revolution and the Muslim Brotherhood’s bid for power. Against the uni-casual thinking about the coup in 2013, Achcar situates the story within a complex of factors — including the weakness and the hypocrisy of the liberal elites; the Muslim Brotherhood’s systematic corruption and complicity with the military, which made them an easy target for the military’s revenge; the constant repression; the role of the regional counterrevolutionary forces; the role of the military and “deep state” as well as the Mubarak restorationists; and the fragmentations and the idealism of the revolutionary left.

In such a context, we can make sense of the successful coup and the rise of anti-Morsi Tamaroud (“Rebellion”) campaign that paved the way to this coup. (85-94) As a scholar of social movements myself, and as one who was in touch with many organizers on the ground, I agree totally with Achcar’s nuanced analysis of the Tamaroud campaign.

As Achcar shows, the movement was founded by Nasserist youth, who are by definition ambivalently loyal to the state, even though some of them later worked with the intelligence apparatus. However, the movement was also genuine, and many leftist organizers also participated in it.

At the same time, the Mubarak forces did infiltrate and fund Tamaroud. In later stages the movement was partially funded by Gulf money. So it was a mess. Nevertheless it would never have formed, let alone gained any momentum, without grievances and anger on the ground against the Muslim Brotherhood and its rule. But it is totally naïve to say either that the movement was state-made (the MB narrative), or an organic genuine movement (the state narrative).

Syria’s “Clash of Barbarisms”

For the chapter on Syria, Achcar starts with a note from his earlier book, where he argued that the Syrian uprising faced two key problems.

The first was the “marked superiority of the regime’s military force” and the second was that the opposition (which ended up fragmenting) lacked resources. Starting with this formula (military and resources) is useful to get to important questions about the Syrian crisis, particularly its militarization and internationalization.

There are many important issues that Achcar doesn’t discuss in detail, such as the business class being the backbone of the regime, the sectarian structure of the military, and the question of the minority communities (which often tend to see the Assad regime as their only protection).

Nevertheless, I believe that Achcar has posed the right question in such a delicate and complex crisis. It is one thing to argue that the “civil uprising” turned into an incredibly brutal war, and another to investigate why and how this happened.

Achcar is certainly wise not to use the term “civil war,” because this is a civil/international war; it is a regime’s war against most of the population, and it is the Islamic State’s (ISIS) war on that population.

It is also a war between Assad and his regional and international backers against many opposition groups, jihadists and ISIS, with their regional and international backers. It is in some sense a war of all against the Syrian people.

As Achcar emphasizes, the United States’ and the West’s priorities in Syria were always to protect their allies and geopolitical interests. U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman General Martin Dempsey in August 2013 stated this clearly:

“Syria today is not about choosing between two sides but rather about choosing one among many sides. It is my belief that the side we choose must be ready to promote their interests and ours when the balance shifts in their favor. Today, they are not.” (Quoted, 21, Achcar’s emphasis)

In other words, looking for the loyal ally played a significant part in the Western parameters in Syria. There was always some outcry in the West after the use of chemical weapons, or when the crisis of refugees escalated, but Syria was also subject to the balance of power and competitions among regional and global powers.

Obama’s Interventionist Non-intervention

It is a fact that regional powers, mainly Saudi Arabia and Qatar, have contributed to the making of ISIS. It is also true that these powers, along with Turkey and Iran, all contributed practically to empowering ISIS, even as they disagreed on practical stances on the crisis.

Assad and his backers target secular opposition groups and population, largely not ISIS. As Achcar explains, both Turkey and Iran, as well as the Syrian regime, are constantly cracking down on Kurds, who in some areas were the only groups capable of fighting ISIS on the ground.

In one sense, all international and regional parties involved agree on two things: to continue militarizing the conflict (and mostly the wrong parties) and continue abandoning the Syrian people.

I appreciate Achcar’s problematization of the idea of U.S. interventionism. He argues that Obama’s “non-interventionist” policy in Syria was in practice interventionist. Yes, the Obama Administration refused to support the opposition with heavy weaponry, but it blessed its allies’ support of opposition groups, including jihadists, which paved the way to creating ISIS and also maintained the upper hand of the Assad regime.

Of course there are many regional and international parties involved. But Achcar’s point is useful against the shallow analyses of interventionism. On this note, Achcar also attacks naïve anti-imperialists, who are also contradictory as they sometime argue against military intervention, but end up practically siding with imperial interests and positions.

Overall, these chapters offer good critical accounts of the very delicate and complex cases of Egypt and Syria. And in both the introduction and the conclusion, Achcar touches upon other cases, such as Tunisia, Yemen, Libya and Bahrain.

It is telling here that Achcar’s first book was received with skepticism — by many scholars and activists alike — and was accused of offering a pessimistic account at a time when many were celebrating. And his second book was received with skepticism of a different kind, charged with offering some glimpses of hope when many see nothing but defeat in the Arab Spring.

But the truth is that Achcar’s argument holds true in both cases when he argues that what we are witnessing is “a long-term revolutionary process that would go on for years, even decades.”

Workers and Thieves

Joel Beinin’s book is divided into four main chapters: “Colonial Capitalism to Developmentalism,” “The Washington Consensus,” “Insurgent Workers in the Autumn of Autocracy,” and “ Popular Uprisings in 2011 and Beyond.” In addition, the book has extremely valuable introductory and concluding chapters.

Beinin offers an excellent historical overview of trade unions and workers’ struggle in Egypt and Tunisia, long before the Arab Spring uprisings as well as in their aftermath. He sheds light on how the specific history in both countries created opportunities as well as limitations to workers’ struggle, along with shaping the trajectory of the events of the uprisings.

History here means the complicated comparative formation of trade unions and political identities, their relation with political parties, the intelligentsia, and NGOs in the respective countries, the structure of economies in both countries from colonial time through postcolonial governments, and how consecutive political regimes navigated their way with structural adjustment programs and neoliberal policies.

In Chapter One, Beinin shows crucial elements that shaped the birth of workers’ unions in both Tunisia and Egypt. His discussion includes both the role of colonial economies (what Beinin describes as colonial capitalism) and the unique features of unions’ formation.

In Tunisia for example, the formation process meant that unions were more independent, something that continued into the post-colonial era. Beinin states:

As early as 1908 Egyptian nationalist politicians — lawyers, journalists, and other modern professionals — embraced workers and led many trade unions. They avoided the language of class until Marxists reintroduced it in the 1930s. The Tunisian nationalist intelligentsia was slower to support workers and their issues, so trade unions became a salient, relatively autonomous actor in the nationalist movement. (9)

Beinin shows the similarities in the history of colonial capitalism in relation to Nasser’s and Tunisian president Habib Bourguiba’s developmental economies (“peripheral Keynesianism” in Beinin’s terminology), followed by the story of the transition from developmentalism to free market policy in Egypt and Tunisia.

Despite somewhat similar economic patterns between the two countries, Bourguiba made more room for the private sector. Most importantly, unions were more autonomous in Tunisia.

In Chapter Two, Beinin discusses how the application of Economic Reform and Structural Adjustments Program (ERSAP) shaped both economies as well as created workers’ unrest. In both countries the initial application of ERSAP met with strikes and riots (in 1977 in Egypt, and in 1984 and 1987 in Tunisia). But the impact of these was different.

Tunisia and Egypt drew opposite conclusions form the IMF riots that greeted their first efforts to implement Washington Consensus policies. Egypt signed agreements with IMF in 1978 and 1987. But Presidents Sadat and Mubarak were concerned that precipitous implementation of Washington Consensus policies would risk another food riot and did not fully implement the conditions of the agreements. In Tunisia, [prime minister] Mzali, who opposed Bourguiba’s decision to rescind the price increase that provoked the January 1984 riots, persisted in implementing the IMF’s policy recommendations. He abandoned the economic populism and faux political liberalization that characterized his first years in office and moved sharply to the right. (43)

An important part of the story is the decade of workers’ strikes in Egypt in the 1990s in response to ERSAP’s escalated in 1993, during a seemingly calm time in Tunisia.

Beinin argues in Chapter Three that one cannot study the history of the uprisings in both countries without studying Tunisia’s phosphate-rich region Gafsa’s rebellion in January 2008 and the Egyptian Mahala workers’ strike in 2007, along with the failed strike in April 2008 which evolved into citywide civil unrest in Mahala and gave birth to one of Egypt’s most important youth movement, the April 6 Movement.

“A Job is a Right, You Thieves”

In 2008 in Gafsa, workers in the mining area protested and some were killed. The brutal repression of president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali created a citywide rebellion.

Beinin explains how the slogan “A job is a right, you pack of thieves,” that appeared during the Gafsa rebellion re-appeared in Sidi Bouzid in 2010. He rightly argues that even when movements are defeated, it is important to look back and study how the culture of protests travels across time from history to the present.

As Beinin shows, it does not make sense to study the uprising without the post-colonial element: the involvement of France/EU and International Financial Institutions (IFIs) with Tunisia, and the United States and IFIs with Egypt. The IFIs’ experts ignored the high levels of poverty and corruption in both countries, and continued to produce inaccurate reports about the success and economic growth in both.

Tunisia was described as an “economic miracle.” In contrast, Beinin notes that:

The Tunisian “economic miracle” was built on its postcolonial relationship with France, and by extension the European Union. It entailed subsidized technology upgrading, politically motivated investments, falsification of data on poverty, and myopic declarations by self-interested French political and economic elites and journalists. Western enthusiasts disregarded the possibility of government falsification of data, the unequal distribution of the fruits of economic growth, and the nature of the jobs created by that growth. They obscured Tunisia’s persisting poverty and unemployment concentrated in the interior of the country and disproportionately among educated youth, and, of course, its appalling human rights record. (57)

During the uprisings in both countries, workers played a critical role. Strikes erupted in Egypt in the last few days before ousting Mubarak (from 6 February to February 11th of 2011) and workers did not stop despite the military regime’s attacks, which were followed by the Muslim Brotherhood rule and back to military regime.

In Tunisia, the local UGTT and leftist organizers played an important role in the Sidi Bouzid protests in December 2010 and early January 2011.The hostility of both post-revolutionary regimes to workers is an important part of the story.

Comparisons and Commonalities

I cannot help but emphasize some of the commonalities in these books. First, against the simplistic political analyses separated from economy, or simple state-centered analysis of the uprisings, both authors examine the neoliberal conditions that led to them and shaped their outcomes. To borrow Beinin’s terms, it is obsolete to analyze the uprisings without explaining the thieves’ side of the formula.

Second, both works urge us to think of critical perspectives about actors in the uprising. If we limit our analyses of uprisings to the cool kids with social media access or major organized groups like Islamists, then we are missing what really happened and the important lessons for the future.

In doing so, both authors are making what I see as an important double-move. On the one hand, they want us to think beyond the simplistic talk about the rise of new actors, defined here as the millennial generation. Beinin for example is telling us a story about the old actors, such as workers, whose role was not only relevant but critical.

On the other hand, while prioritizing the economic and social picture, these authors are not rigid structuralists who analyze the events in narrowly economist terms. But they do situate agency in structure and discuss the role and the limitation of agency within their shifting contexts.

Both are highly sensitive to how history informs the present. Past struggles and movements, victories and defeats alike, shaped what happened in the Arab Spring. But both books are also correctives against the “presentist” analyses of the Arab Spring and its problems. (Presentism may mean different things. Here I mean only the tendency to read present-day phenomena separate from history, or without proper historicization.)

An expert social historian who is very knowledgeable about labor in the region, Beinin shows how colonial and post-colonial formations shaped trade unions in Tunisia and in Egypt. Achcar also discusses the historical roots of the formation of the liberal/Arab nationalist temptations in the revolution, which made it an easy target for counter-revolution, and the history of the Islamists’ tense relations with the military.

Both also offer valuable in-depth comparisons between Egypt and Tunisia and their respective uprisings. While this explicit comparison was not Achcar’s main goal, he nevertheless does a good job of investigating “the Tunisian ‘model’ and its limits.” (157-165)

Yes, there seems to be a procedurally functioning democracy in Tunisia. But this model is based on a compromise between the Islamists, the liberal elite, and the old regime. The compromise cannot last. But what matters more is the social and economic grievance that the post-revolutionary administration failed to meet.

Both books do well in going beyond the shallow comparison of a strong military and pragmatic opportunist Islamists (in Egypt) versus a weak military and wise Islamists (in Tunisia). Both authors show the complex relation between the Islamists in their respective contexts and the regime (old and seemingly new).

What is more important, both authors discuss in detail how the post-revolutionary administrations in the two countries rushed back to neoliberal policies, and have done nothing with regards to the social and economic grievances that fueled the uprisings.

Both Tunisia’s Islamist Ennahda party and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood government denounced workers’ strikes and escalated the repression of workers. This does not seem to secure a long lasting stability, let alone meet the demands of the uprisings.

Finally, it is interesting to rethink how the liberal intelligentsia in both countries — not only the regimes — betrayed workers. In both countries, they were not only historically unsympathetic to workers’ struggles and organizing, but also blamed workers for not being political enough. And of course, workers themselves blamed those elites for not caring about workers.

Apart from these commonalities, it is interesting that some activists in the region have criticized both books, especially Achcar’s, for relying heavily on secondary sources. They suggest that some ethnography and/or first hand interviews would strengthen the analyses.

This is a good point. But the truth is that both authors are not strangers to the region. And in the context of the dramatic changes in Egypt, it is almost impossible to do any type of fieldwork.

With respect to Workers and Thieves, I appreciate how Beinin discusses the interesting relations and the unfortunate skepticism between workers and some of the leaders of the youth movements, such as the April 6 Movement.

I admire Beinin’s emphasis that the workers’ and youth’s role in the uprisings were not mutually exclusive. But I would have loved for him to have discussed this point — the workers’ relations with the millennial generation — in greater depth in the Tunisian case.

With respect to Achcar’s book, I would have loved more engagement with Gramsci’s theorization and specifically with the concepts of relapse and “morbid symptoms.” But at the same time, I appreciate that the book is free from theoretical jargon, which makes it accessible to a wider audience.

The Future: Confronting Reaction

Overall, both works are also reminders that the very conditions of the uprisings are still there. Yes, uprisings may not erupt again in the immediate future. But the change in the region is far from over. Both also remind us to think outside the box about the future of revolutionary actors in the region.

It is one thing to admit that the uprisings were defeated, and another to identify the “right” reasons and lessons about this defeat. Both works invite us to think of counter-revolutions in complex terms. These are not simple nation-state based forces and policies, but regional and global.

It is easy and simple to blame people in the region for the troubled outcome, but the truth is that superpowers and International Financial Institutions, and not only the Gulf States, were in the forefront of efforts to combat, stop, or contain the uprisings Counter-revolutions are complex and tricky (especially when popular violent and sectarian beliefs are inserted into regimes’ policies).

These analyses are an invitation for us to consider cases where naïve anti-imperialists are similar to liberals who do nothing but cry out about atrocities overseas without questioning western governments’ role in making these happen, and when they offer abstract and shallow analyses about complex imperial interventions, without building critical anti-imperialist global solidarities.

As a serious rightwing menace is now on the rise in the USA, with potential severe global impact, the empire will be more dangerous, regardless of how “interventionist” it proves to be. We need to get the critical narrative right, one part of which is to distance ourselves from liberal analyses of conflicts in the Middle East and crisis and contention at home.

March-April 2017, ATC 187