Against the Current, No. 186, January/February 2017

-

Fighting Back for Survival

— The Editors -

Obama's Legacy & the Rise of Trump

— Malik Miah - The Black Lives Matter Response to Trump

-

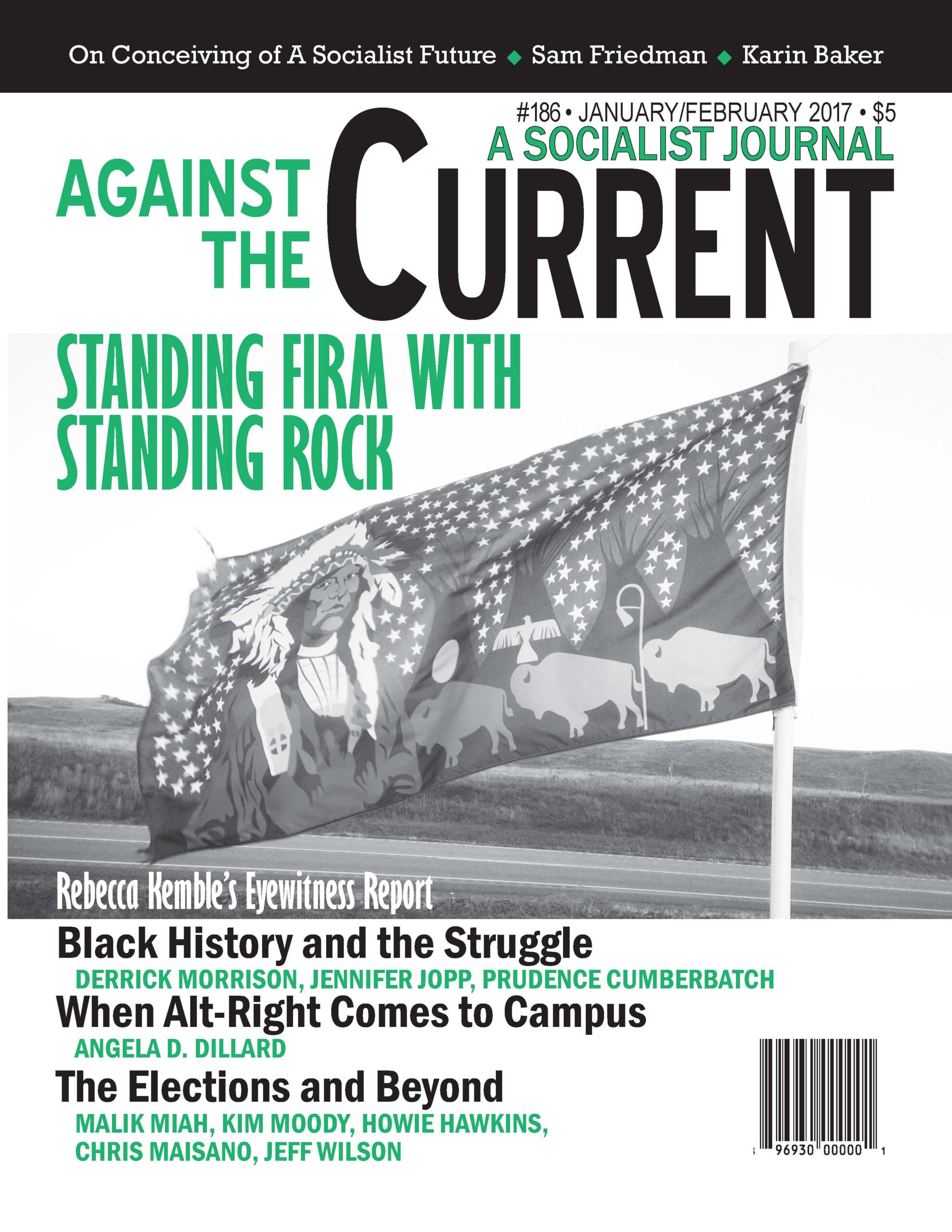

Eyewitness at Standing Rock

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

Canada's State of Reconciliation

— Gayatri Kumar - New Trial for Rasmea Odeh

-

MA Stops Charter School Expansion

— Dan Clawson & John Fitzgerald -

Chicago Teachers Settle Contract

— Robert Bartlett -

When the Alt-Right Hits Campus

— Angela D. Dillard - Putting the Racist Flyers at University of Michigan in Context

- Faculty & Staff Statement Against Racism

-

Creating a Socialism that Meets Needs

— Sam Friedman -

A Better World in Birth

— Karin Baker - US Politics After November

-

Who Put Trump in the White House?

— Kim Moody -

The Green Party After the Election

— Howie Hawkins -

Stein-Baraka Ticket

— Howie Hawkins -

Hope in Dark Times

— Chris Maisano -

Trump Not "Exceptional"

— Jeff Wilson -

Actually, I am Anti-Police

— Alice Ragland - Black History Retrospective

-

Birth of the Abolitionist Nation

— Derrick Morrison -

"The Slave-Holding Republic"

— Jennifer Jopp -

How "Race Neutral" Policy Failed

— Prudence Cumberbatch - Reviews

-

Survival Is the Question

— Michael Löwy -

Macaroni & Cheese and Revolution

— Ursula McTaggart

Jeff Wilson

Trump: A Graphic Biography

By Ted Rall

Seven Stories Press, $16.95 paper.

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight. Then we shall clearly realize that it is our task to bring about a real state of emergency, and this will improve our position in the struggle against Fascism. One reason why Fascism has a chance is that in the name of progress its opponents treat it as a historical norm. The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are “still” possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge — unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which gives rise to it is untenable. — Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History

OVER THESE PAST few months I keep coming back to the above quote from Walter Benjamin — a German Jew who died fleeing the Nazis and for whom the nature of fascism was always a central point of both deep anxiety and thought. It is because of this that his words offer an important lens for reflecting on Donald Trump’s presidency.

This might be hard for many to admit, but Trump’s campaign and presidency — the racist, sexist, heteronormative and white supremacist views it exults — are in fact not exceptional. Trump’s rise does not reflect a “state of emergency” but rather is much closer to the status quo then many of us are comfortable admitting.

Mine is not an elitist critique extended by many liberals who perceive their fellow Americans as uneducated, racist or politically ignorant. Rather Trump should be viewed as a particular articulation of the already present and deeply rooted systems of structural and institutional racism and sexism.

One need only consider the gender wage gap, staggering levels of poverty and health disparities for minorities, a state system that sanctions its “low level bureaucratics” (police) to gun down Black and brown people in the streets with near impunity, and a prison industrial complex that targets minorities.

Following Benjamin then, we should not be amazed political characters like Trump are “still” possible — this view will not increase our chances of defeating the types of hatred consolidating around him.

Written in comic strip form, Ted Rall’s new book Trump: A Graphic Biography represents this year’s Republican president elect and his bald flirtations with fascism.

Where He’s Coming From

Rall rightly begins the book not with Trump, but focuses instead on the context from which his campaign became possible. He situates nativist tendencies that have fomented in the country for years as the foundation from which Trump is able to rail against immigrants both from Latin America and the Middle East.

Well-worn phrases from Trump, like “they’re killing us at the border” and his pledges to deport 11.3 million people without documentation, are astutely juxtaposed with Stalin’s removal of (for example) Tatar and Polish populations in the Soviet Union, as well as Hitler’s desires for forced removal of ethnic populations in Germany. It is through these parallels that we gain a clear sense of the possibilities during Trump’s presidency.

Trump’s alignment with right-wing populism is also situated within a larger socio-political context. For instance, we are reminded that the financial collapse of the housing market is still having devastating effects on people’s lives despite extraordinary gains by the wealthy.

This economic disparity is framed in the book as a conscious choice in Washington to save capitalism, leaving little question with the reader as to why there is a deep hatred of the government and mistrust of Congress, and little doubt as to why Trump’s anti-establishment rhetoric found traction.

Given the political and economic context the book gives to Trump’s rise, it is important to note that Rall does not stray far from straight biography. Trump’s business dealings — from paying slave wages of $5 an hour to undocumented workers from Poland in 1980, to his connections with the Genovese crime family, to running tenants out of Barbizon Plaza in NYC, to not renting to people of color in the 1970s, resulting in a federal lawsuit — are all highlighted.

These examples demonstrate clearly that Trump’s so called “keen business sense” is more thuggish then innovative — a quality we will undoubtedly see more of during his term as president.

The Making of a Monomaniac

Rall also delves into the ways Trump’s personality was formed by recounting his childhood and relationship with his father, his time in the military academy, marriages and infidelities. These reveal his cocky, self-assured and even monomaniacal focus.

From these moments Trump’s life reads as a caricature of a rich kid who has had everything given to him nearly unimpeded. In this sense the book does not offer much that is deeply insightful but rather fills in the details one would assume such a privileged life would allow.

Perhaps the greatest insight revealed in the book is the interview snippets offered by experts on the political and potential meaning of Trump’s emergence. The most powerfully of these is from Robert Paxton, who is Rall’s former professor and author of many works on fascism.

For Paxton, fascism in this country will, unsurprisingly, have a distinctly American flavor and not reflect the more militarized images of uniforms and marches we saw in Germany, Italy and Spain. He does, however, note similarities between Trump’s charismatic popular appeal with that of former fascist leaders: “He’s very spontaneous: He has a genius for sensing the mood of a crowd and I think to some degree Hitler and Mussolini had those qualities also.” (123)

From this we can understand Trump as responding to elements of micro-fascism (racism, sexism, xenophobia and white supremacy). These are finding room to resonate together and could form into a more robust fascist political movement.

This might be the most dangerous aspect of Trump’s rise, as reflected in the chapter title “The Accidental Authoritarian.” What is clear is that Trump is not an ideological fascist, but rather responding to and by default providing a space for people to come together under racist and nativist banners.

If he appears to have no set ideology except a commitment to corporatism and cronyism, nonetheless Trump’s election has opened up spaces for individuals and groups to express views of hatred openly that otherwise would have been muted.

Sadly, Donald Trump is neither exceptional nor a representation of some new “state of emergency.” This is why our task is to challenge all these deeply embedded configurations of hatred and in doing so to bring about what Walter Benjamin would have called “a real state of emergency” that will challenge not only structural and institutional racism and sexism, but also the various forms of hatred Trump has helped to embolden.

January-February 2017, ATC 186