Against the Current, No. 185, November/December 2016

-

On Imperial Conundrums

— The Editors -

Institutional Racism & the Thirteenth Amendment

— Malik Miah -

The Enormous Profit of Thirst

— Josiah Rector -

Environmental Racism in Santa Cruz

— Michael Gasser -

AIDS: The Struggle Continues

— Sam Friedman -

Indiana: The Culpability of Politicians

— Sam Friedman -

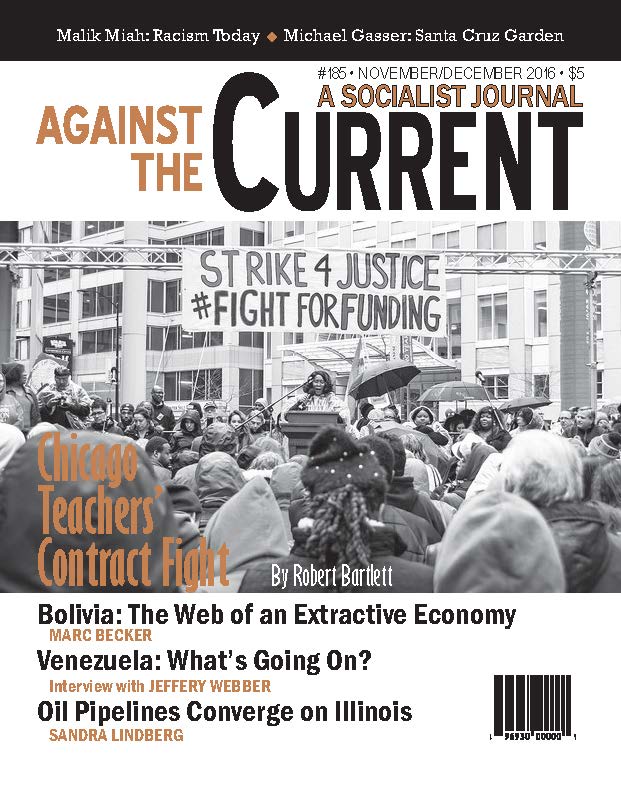

Fighting for "Schools We Deserve"

— Robert Bartlett -

Budgeting Disaster and Charters

— Robert Bartlett -

Review: Whose Education? Whose Control?

— Marian Swerdlow -

Bolivia's Extractive Economy and Alternatives

— Marc Becker -

Venezuela: What's Going On?

— an interview with Jeffery Webber -

How Woodrow Wilson Entered World War I

— Allen Ruff -

Oil Pipelines: Converging in Illinois

— Sandra Lindberg - Reviews

-

The Wikileaks Files

— Cliff Conner -

A Nation Behind Bars

— K. Mann -

Weaponizing Modernist Culture

— Alan Wald -

The Paradox of Che Guevara

— Peter Solenberger -

South Africa: The Radical Thought of Rick Turner

— Alex Lichtenstein -

An Anti-Apartheid Class Revisited

— Billy Keniston -

Response: Does Being a Revolutionary Mean Being a Terrorist?

— Rebecca Hill

Robert Bartlett

TEACHERS ARE BELEAGUERED by unrelenting attacks on their jobs and security. All teachers feel vulnerable, but the risk is greatest in low-income areas of the city where neighborhood schools are targeted by the growth of charter schools.

Today there are approximately 394,000 students in both the public and charter sectors in Chicago. Both public schools and charters receive the same student-based funding and many charter advocates complain about the amount.

With 530 district schools and 130 charters, 58,000 students attend charter schools. Despite teacher and community protest, 53 public schools were closed after the 2012 contract was signed — seemingly the Board’s way of getting back at strikers and their supporters.

At the same time that public neighborhood schools closed, new charters opened in the same Black and Latino neighborhoods on the south and west side of Chicago (http://www.ctunet.com/quest-center/research/black-and-white-of-chicago-education.pdf).

This is a double whammy as these communities were first decimated by job losses and disinvestment over the last 30 years, and then charter schools followed to destabilize their neighborhood schools, further weakening the social cohesion that makes neighborhoods viable.

Although the ideology for introducing charter schools was that their supposedly innovative curriculum would spur public schools to improve, a steep decline in public school enrollment has weakened neighborhood public schools and their financial base. Yet charters almost uniformly have fewer special education students and lower levels of English-language learners, who cost more to educate.

Charters have been aggressively recruiting public school students from neighborhood schools through mailings. This probably has more to do with a Darwinian struggle for students in order to secure more funding from a dwindling pot. Even the more successful networks like Noble Street have made their gains through a relentless focus on test prep, and policies that push out students who don’t “fit” their model by imposing financial penalties when students fail to comply with school policies.

One positive development over the last period has been the growing unionization of some of the charter networks including the largest group of 15 schools established by the politically connected United Neighborhood Organization.

Under pressure of a public scandal about the school leadership siphoning construction money to relatives of their board of directors, UNO signed a contract with their teachers three years ago.

UNO teachers went to the brink of a strike before coming to a tentative agreement on October 19th. In a sign of the growth of teacher consciousness 531 of 532 teachers had voted 96% in favor of a strike. Conditions in charter schools are even worse than those in the public schools with teachers expected to work more days per year than are required by the state, class sizes that are too large, and a high turnover. UNO teachers wanted a contract that would increase their retention rate and allow them to build careers as educators.

Early reports of the proposed two-year settlement indicate that management backed off of their demand to end the pension pickup and came up with money for a raise.

November-December 2016, ATC 185