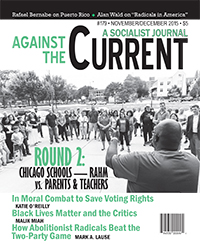

Against the Current, No. 179, November/December 2015

-

Global Lessons of A Catastrophe

— The Editors -

BLM: A Movement and Its Critics

— Malik Miah -

Can Chicago Teachers Win Again?

— Robert Bartlett -

Teachers in the Crosshairs

— Marian Swerdlow - Grace Lee Boggs (1915-2015)

-

U.S. Workers & Puerto Rico's Crisis

— Rafael Bernabe -

When Radicals Beat the Two-Party System

— Mark A. Lause -

Moral Combat: The Right to Vote

— Katie O'Reilly - Review Essay

-

Review Essay: Reaching for Revolution

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

A System That Makes You Breakable

— Leighton Stein -

Incarceration & Resistance

— Brad Duncan -

Anti-Capitalism & Queer Liberation

— Alan Sears -

When Marxism Is Kids' Stuff

— Julia L. Mickenberg -

The Art of Carnage

— Dianne Feeley -

A Memoir of Life in Struggle

— Barry Sheppard -

A Reponse on Trotsky

— Paul Le Blanc

Brad Duncan

Captive Nation:

Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era

By Dan Berger

University of North Carolina Press, 2014, 424 pages, $34.95 cloth.

The Struggle Within:

Prisons, Political Prisoners, and Mass Movements in the United States

By Dan Berger

PM Press/Kersplebedeb, 2014, 128 pages, $12.95 paperback.

CAPTIVE NATION IS a bold reconsideration of the role of prisons and African-American prisoners spanning the southern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, Black Power and the New Left, and the Black Nationalist renaissance of the 1970s.

Dan Berger offers a fresh look at the impact that routine incarceration had on the early Civil Rights Movement, the influence of prison writings — from Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to George Jackson’s Soledad Brother — on a generation of young activists around the world, the vibrant international campaigns to free Black political prisoners from Angela Davis to Dessie Woods, and organized prisoner resistance from radical study groups to prisoners’ unions to riots and uprisings.

Painstaking attention is paid to the stories of the Soledad Brothers and Angela Davis, the role of independent pro-prisoner and Black print media, and the ideological and political significance of left and nationalist movements that organized inside prisons such as the Republic of New Afrika.

Berger’s interdisciplinary approach utilizes political geography, gender studies, legal theory and cultural analysis alongside archival research and dozens of interview with key participants.

Berger’s focus on the 1970s is crucial in seriously examining a period of radical social movements that historians have generally overlooked. Too often historians consider the early, optimistic years of Black Power and seemingly lose interest after the very early 1970s. Taking a serious look at the nitty gritty of the long 1970s — years of repression, political defeats, sectarian battles, and reactionary blacklash — deepens our understanding of the whole period.

Berger also sheds a light on perhaps the most politically radical and under-appreciated currents of a period when revolutionary socialism, nationalism of the oppressed, and internationalism were organically interwoven. Berger, whose roots are in prisoner solidarity activism, is also the author of The Struggle Within: Prisoners, Political Prisoners, and Mass Movements in the United States. This slim, efficient, remarkably useful book makes a perfect introduction to the topic.

Movements Defined by Imprisonment

Unlike the sprawling Captive Nation, The Struggle Within looks at the issue of prisons and political prisoners up through the present and is designed for newer activists. Highlighting resistance behind bars today, it brings some of the many story lines of Captive Nation up to date.

The Civil Rights and Black Power movements are often portrayed as quite separate, located at opposite ends of the 1960s both chronologically and politically.

Dr. King wouldn’t have cared much for the Black Panthers, it is often implied, and would have liked the sharp left turn of the 1970s even less. One was peaceful, liberal, and integrationist; the other was violent, separatist and communist.

One of Captive Nation’s first important points is to show a remarkable continuity between the era of the Dr. King and the era of Assata Shakur. What connected these seemingly distant currents in post-WW2 Black politics was what Berger calls an “intimacy with incarceration.” (24)

From the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to the Black Liberation Army, widespread imprisonment created a bond among activists, challenged the very legitimacy of the criminal justice system, created another battlefield from which to engage the enemy, erected a stage from which to tell the world about the condition of Black people in America.

The Nation of Islam is credited with pioneering work with prisoners during the 1950s in California, organizing for prisoner literacy and health along with their clear, defiant message of unbowed Black manhood. “Don’t be shocked when I say I was in prison” Malcolm X said in his “Message to the Grassroots.” “You’re still in prison. That’s what America means: prison.”

As the Black Panther Party and other Black radical movements saw their leaders imprisoned and potentially facing execution on trumped-up charges, from Huey Newton to Angela Davis, the political prisoner emerged as the face of the Black Power and radical Left movements, becoming global ambassadors of the revolution.

Berger uses the term “dissident prisoners” to describe both people who were incarcerated for their political activism and individuals incarcerated for apolitical crimes who became politicized while behind bars. Berger demonstrates how the autobiography of the politicized prisoner, especially The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) and Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice (1968), emerged as a defining influence on the Black awakening and indeed insurgent anti-colonial movements around the world.

As state repression intensified by the late 1960s, activists increasingly put campaigning for dissident prisoners at the center of their work, knowing that if the state could get away with imprisoning and even executing movement leaders then worse repression would surely follow.

The state used imprisonment to put movements on the defensive, to isolate and silence leaders, and to contain the whirlwind of interlocking struggles exploding nationwide. In response movements used campaigns for dissident prisoners to politicize the broader public and build bridges between struggles.

The ascendant Chicano movement took up the case of Los Siete de la Raza, six Latinos falsely accused (and eventually acquitted) of killing a police officer in San Francisco. Puerto Rican activists campaigned for imprisoned members of the Young Lords Party (whose newspaper would refer to New York’s Puerto Rican ghettos as “prisons of the streets”).

Campaigns by dissident prisoners increasingly created a sense of a shared struggle, a spirit of internationalism, that impacted the movements outside. Berger is very keen to illustrate that dissident prisoners were viewed by movement activists on the outside not as passive subjects in need of charity, but rather as true movement leaders, intellectuals and artists whose lived example proved that the state was not all-powerful.

Soledad Brothers and Angela Davis

Berger uses the overlapping legal cases of the California prisoners George Jackson, Ruchell Magee and prison activist Angela Davis to illustrate in remarkable detail how prisoner intellectuals, prison solidarity, and the concept of heroic insurrectionary prisoner resistance shaped the movement.

George Jackson was radicalized while incarcerated, his political evolution spurred by brutal conditions and his own self-education. (“I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky and Mao in prison and they redeemed me.”) From the mid-1960s Jackson embraced a vision of socialist revolution influenced by the anti-colonial revolutions.

In addition to leading study groups, Jackson wrote prolifically. He increasingly focused on the role of the guerrilla, armed struggle, and the idea that heroic feats of resistance could inspire others to rebel. He also wrote graphically about the conditions faced by prisoners, often signing his letters “From Dachau with love.”

Jackson became an international icon of Black prisoner resistance in 1970 when he was charged with killing a prison guard along with two comrades, together known as the Soledad Brothers. The campaign to free the Soledad Brothers went global, involving everyone from leading French intellectuals (Jean Genet and Jean Paul Sarte were prominent voices) to a young Black philosophy professor and Communist Party member, Angela Davis.

A book of Jackson’s writing, Soledad Brother (1970), an international smash, “shattered the idea embedded in rehabilitative penology, that complacency accrues with time spent in the cage,” Berger writes, “Instead of making Jackson more docile and palatable, prolonged punishment made him more radical and militant.”

Angela Davis, already somewhat famous for being an academic prodigy hated by California Governor Ronald Reagan, quickly became the leader of the campaign.

In August of 1970 Jackson’s teenaged brother Jonathan attempted to free the Soledad Brothers by holding a judge and others hostage, a failed attempt at a courthouse insurrection that killed four people including Johnathan Jackson and a judge and led to Davis being charged with providing Jonathan Jackson’s weapon.

Davis fled California an outlaw icon, cheered by supporters and hunted by police. Once arrested, Davis was both a symbol of solidarity with Black radical prisoners and an imprisoned revolutionary herself. Davis was arrested and faced charges along with Ruchell Magee, who had survived the courthouse catastrophe.

The Angela Davis case brought global attention and made her a hero to wide sectors of the public beyond the reach of the organized Black Power and leftist organizations. Her struggle could connect many struggles. The November 1970 issue of The Black Scholar, which covered the prison movement consistently, stated emphatically that “Angela Davis is campus, is community, is vanguard.”

The mass media tended to portray her simultaneously as a bomb-thrower and a sex kitten, motivated by racial revenge and lust for George Jackson. Berger takes a very deep look at how Davis was interpreted and reinterpreted by the media and even the movement, especially sexualization and its use against Black women historically.

The prosecution called her a “prisoner of lust.” Even some ostensible supporters relished this focus on her looks and love life, the Rolling Stones’ tribute song “Sweet Black Angel” being one particularly cringe-inducing example.

Her legal campaign, of which she was co-council, was successful in winning an acquittal. Ruchell Magee fought to represent himself in court, arguing that given the legal standing of Black people in America, given the situation faced by prisoners, the armed raid on the courthouse was a slave uprising.

Berger seriously investigates the politics of gender and masculinity at work in the lives of Jonathan and George Jackson and in the radical prison movement more generally, noting that the raid on the courthouse was a “hypermasculine vision of prison struggle.” He looks at how sex-segregated prisons, the affirmation of Black manhood in the face of white supremacy, and the then-popular concept that a courageous show of physical force by a bold revolutionary could spark political change, converged to create the problematic idea of the Black dissident prisoner as superhero gladiator:

“At the same time, Jackson’s antiracist critique revealed the increasing significance of the gendered fault lines accompanying this seismic shift in the American racial landscape. Simply put, he was the product not only of the Cold War patriarchal culture but also the sex-segregated institution in which he came of age. His masculinist appeals revealed the carceral future awaiting millions of black men while appealing to the notion of restorative patriarchy common to black nationalist groups that recruited inside prisons during the early 1960s, most centrally the Nation of Islam. His radical critique of American political economy did not obfuscate his own allegiance to a conservative, patriarchal notion of respectability.” (123)

The botched, deadly courthouse raid was met with apprehension in the movement too. Davis’ comrades in the Communist Party defended Davis, but distanced themselves from Jackson’s violent actions.

Huey Newton had just been released from prison and despite the Black Panther’s bombastic public rhetoric, the Party leadership was split on the raid with Newton withdrawing support in a move that exposed growing disagreements nationally over the role of armed struggle and the “heroic guerrilla.”

The Movement Outside

As issues related to prisoners and prisons continued to take center stage in Black Power and the New Left, American popular culture was increasingly fascinated with prisoners and the idea that they represented the confinement of the human spirit. Johnny Cash recorded a record in prison, so did B.B. King. Bob Dylan wrote a moving song about George Jackson, his first political song in many years, while jazz artist Archie Shepp wrote songs for prison uprisings.

The story of George Jackson’s violent death in prison in 1971 prison is told here in remarkable detail, as well as its role in sparking the pivotal subsequent uprising at Attica State Penitentiary in New York. In the prison movement and in Black radical leftist and nationalist circles, Jackson would loom as large in death as in life.

Jackson’s personal and political impact was felt everywhere there were dissident prisoners. The year after his death the “Tear Down The Walls” prison activist conference was held in Berkeley, the Harriet Tubman Prison Movement brought together Black women prison activists, the radical journal Crime & Social Justice was launched, and organizations like the Prisoners’ Union were taking root.

Another key aspect of the blossoming radical prison movement of the early 1970s was the focus on women political prisoners, chiefly women who found themselves in prison after resisting rapists, abusive partners or white racist attacks. Berger looks at the campaigns to free women such as Dessie Woods, Joanne Little, Yvonne Wanrow and Inez Garcia.

This development further broadened the definition of political prisoners and opened the door to cross-fertilization between the prison movement and the women’s movement, although Berger points out that only multiracial and women of color-led organizations within the women’s movement really took up this banner.

Citizens of a Captive Nation

Captive Nation also seriously investigates how the ideologies of Black Nationalism and the Black left evolved over the whole course of the 1970s and into the early 1980s, way beyond the parameters of most historical books on Black radicalism. One of the key organizations that Berger digs into is the Republic of New Afrika, an African-American national liberation movement founded in Detroit in 1968 with the aim of building an independent Black republic in the Deep South.

Berger notes that “New Afrikan politics appealed to a broad cross-section of the black liberation movement,” ranging from veterans like Queen Mother Audley Moore (with her roots in Garveyism and the Harlem Communist Party of the 1930s) to socialist intellectuals like Grace Lee and James Boggs, poet/playwright Amiri Baraka and others in the Black Arts Movement, to exiled self-defense icon Robert F. Williams, from traditional cultural nationalists to Black communists. The RNA articulated Black nationality in North America in concrete terms, taking seriously Malcolm X’s belief that land is the basis of all independence.

The RNA also grew quickly because it took up and extended an argument that resonated with prisoners. The notion that New Afrika as a nation formed by slavery extended the position of black prisoners (as) imprisoned by white supremacy long before they were incarcerated. The RNA’s ongoing work in prison and with prisoners gave this concept greater materiality than had been present when Malcolm X first popularized the metaphoric prison of racism. New Afrikans claimed that prisoners were on the front lines within the prison that held all black people. Staking their authority “by the grace of Malcolm,” New Afrikans extended his message that the black condition involved perpetual imprisonment. (234)

The RNA’s efforts to establish itself in Mississippi were barely underway in 1971 when a massive FBI raid of their headquarters put nearly the entire leadership in prison, including leader Imari Obadele. The RNA organized in prison iin part out of necessity, taking up George Jackson’s call to educate and cohere Black prisoners into a fighting movement.

The growing influence of the RNA inside the prisons, especially from the mid 1970s forward, is illustrated by the large number of high-profile Black Panther and Black Liberation Army prisoners who started identifying as New Afrikan citizens, from Assata Shakur to Jalil Muntaquim to Russell Maroon Shoats.

Readers interested in the RNA should also read another recent groundbreaking work, Akinyele Umoja’s excellent We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement (NYU Press, 2014). Hopefully other contemporary historians will follow the lead of Berger and Umoja and give the RNA experience the scholarly attention it truly deserves.

Prisoner Media, Prisoner Culture

Nowhere was the growing influence of New Afrikan politics seen more abundantly than in the pages of radical prisoner newspapers. These ranged from crudely printed, highly underground newsletters using improvised measures (sometimes with just toilet paper, gelatin and pen caps), to more traditional newspapers written and edited by prisoners but printed by supporters on the outside.

Print culture was the backbone of prison organizing in the second half of the 1970s. These publications marked a new era in prison politics, enabling prisoners to continue functioning as political actors — to read the news, to write their opinions, and debate political theory —- after the high tide of prison organizing had ebbed. They provided prisoners with a means to define the issues on their terms. With less public backing and little in the way of mass movement to support them, prisoners used media to sustain relationships with other prisoners and sympathetic outsiders. As collective action became more difficult, writing and editing provided an opportunity for politically conscious prisoners to continue working collaboratively with others on both sides of prison walls. (226)

There were roughly eight prison newspapers that articulated New Afrikan politics, in addition to other sympathetic Black and leftist periodicals that focused on prisoners. At Marion prisoners started a newspaper called Black Pride; its motto was “Everything is Political.” The paper included articles on prison conditions, writings on George Jackson and Angela Davis, messages from the Republic of New Afrika, but reflected a mix of ideological influences from communism to the Nation of Islam.

Black Pride exemplified the way that New Afrikan politics sprouted through the cracks of a federal penitentiary. The mimeographed periodical showed that the divisions between revolutionary nationalism and cultural nationalism, blurry on the street, could collapse entirely in prison. The erasure of these distinctions moved traditional cultural nationalism to the left (as seen from the journal’s overtly political disposition) and revolutionary nationalism to the right (as seen from its discussions of black women). (240)

Another example that Berger investigates is The Fuse, a paper written by a collective of New Afrikan inmates at Statesville Prison in Illinois known as the New Afrikan Prisoners Organization (NAPO) and printed by supporters in Chicago.

In 1977 NAPO published We Still Charge Genocide, a blistering indictment of Black political bondage that updated the 1951 book We Charge Genocide by African American communist William Patterson. The Fuse covered the prison movement, especially local struggles in the Midwest, and eventually took on other publishing projects such as a Black Liberation calendar.

NAPO and The Fuse were largely responsible for organizing support of 17 prisoners facing murder charges for their role in a 1978 revolt at a prison in Pontiac, Illinois, known as the Pontiac Brothers. The New Afrikan movement was in a position to garner support from leading Black figures like Louis Farrakhan and Dick Gregory as well as “new communist movement” groups.

The acquittal of the Pontiac Brothers in 1981 was a major victory in an era when the radical movements of the early ’70s were almost entirely extinguished and the anti-left, anti-black backlash of the Reagan years was coming into full effect.

The Spirit Armed

Arm The Spirit was another essential prisoner newspaper animated by a New Afrikan perspective. In addition to covering prisons, Arm The Spirit always contained articles on Black radicalism around the world, and also regular coverage of other national liberation struggles in North America, particularly the clandestine Puerto Rican independence group the FALN and the indigenous American Indian Movement.

Militants of the FALN were increasingly imprisoned in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the New Afrikan approach to challenging the legitimacy of the judicial system as an oppressed nation was often employed. Radical movements for national liberation and socialism were small and isolated by this period, but behind bars hard times necessitated unity and perseverance.

Another important newspaper that covered dissident prisoners extensively was Midnight Special, a project of the NY chapter of the National Lawyers Guild. Named after a song made famous by blues singer and former inmate Huddie Ledbetter (“Leadbelly”), this was a leading source of up-to-date information about imprisoned Black Liberation Army members like Assata Shakur, debates within the prison movement, and dissident prisoners nationwide in a period when radical periodicals were markedly declining in their reach.

The paper sought to facilitate a coalition among prisoners at different facilities and between prisoners and social movements. While Midnight Special was oriented toward prisoners themselves, its editors saw a special role in securing public attention for prison struggles. “Outside support of inmate struggles is indispensable if the type of repression that occurred at Attica is not to be repeated,” the editors declared, affirming their intention to “remove some of the barriers that exist between the outside and the inside.” The paper walked a fine line between publicity and anonymity; to avoid diverting attention from the writings of imprisoned intellectuals who at times had to remain anonymous to avoid repercussions, the editors, too, remained anonymous. Anonymity allowed the paper to print the prisoners’ honest appraisals in which they described their confinement and the painful divisions, generational as much as spatial and emotion, it caused. (242)

The New England Prisoners’ Association published NEPA News; the Coalition for Prisoner Support in Birmingham, Alabama published the CPSB Newsletter; a coalition of prisoners and nonprisoners in Indiana published The Real Deal; and Black magazines like Brooklyn’s Black News, published by the East Organization, and The Black Scholar continued to provide a vital print platform as movements dwindled.

One product of the effort to maintain morale and coherence in a time of setbacks for dissident prisoners was the creation of Black August. “Black August began as a way to commemorate the relatively recent history of prison radicalism alongside the long history of slave rebellions,” Berger writes, “As the tradition continued, though, it came to reflect a longer black freedom struggle.”

Part political holiday, part revolutionary ritual of remembrance, Black August reframed a number of events that all took place in the month of August: the beginning of the Haitian Revolution (1791), Nat Turner’s rebellion (1831), the birth of Marcus Garvey (1887), the March on Washington (1963), Watts rebellion (1965), and of course the martyrdom of the father of prison radicalism, George Jackson.

“We figured the people we wanted to remember wouldn’t be remembered during Black History Month” said co-founder Shujaa Graham, “so we started Black August.” Black August continues to this day, celebrated with annual events inside and outside prison.

An organization that Berger investigates, which very few historians have previously written about, is the one that initiated Black August, the Black Guerrilla Family. An outgrowth of George Jackson’s legacy, the Black Guerrilla Family has a foot in left-wing Black Nationalist politics and a foot in prison yard criminality; a hybrid organization born from prison conditions.

Berger looks soberly at the Family’s mix of radical politics and gang activity, noting that “The decline of socialist organizations such as the Black Panther Party left an absence that was filled by heterodox groupings that combined politics with predatory behavior.” (260) The FBI was convinced that the Family was heavily connected to armed groups on the outside, but in reality it operated almost entirely inside prison.

In many regards Captive Nation ends with a movement nearly defeated, and with the extreme repressive prison conditions of the late 1960s now numbingly commonplace. But dissident Black prisoners emerged as heroes of resistance to a whole global generation of revolutionaries, proving with their actions that the U.S. state was not so all-powerful as was feared.

Yet the fact that black prisoners have, time and again, emerged as spokespeople for and theorists of a different kind of freedom shows that nothing can be taken for granted and that the tragedy of American imprisonment — like the greater tragedy of racial state violence of which it is a part — is neither preordained nor permanent. (279)

Introduction for Activists

Dan Berger’s The Struggle Within is a model for accessible, jargon-free writing about social movements. Easily read in one sitting, it will bring readers up to date regarding political prisoners in the United States, the history of the movements that produced these prisoners, organizing inside and outside prisons walls up to the 2010s, and contemporary issues facing prisoners and the anti-prison movements.

Berger places the political movements represented amongst the ranks of political prisoners into a handful of categories. Movements for national liberation are of course prominent, particularly Puerto Rican, Chicano/a, and Indigenous struggles. This also includes Black or New Afrikan movements, which are profiled in the most depth.

Also profiled are radical pacifists (Berrigan brothers, Ploughshares movement, Catholic Worker), armed leftist groups that sprang from the 1970s such as New England’s United Freedom Front (known as the Ohio 7), direct action ecological and animal liberationist movements, and contemporary anti-militarists and whistle-blowers like Chelsea Manning.

Berger looks at the repression and extreme sentencing faced by direct action environmentalists, known as the Green Scare, such as Marius Mason. As a slim introduction, though, The Struggle Within does not spend time asking the hard political questions that readers will undoubtedly have around tactics and strategies. The book concludes with an extensive listing of activist organizations and reading suggestions.

The 2010 publication of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander, has contributed significantly to a renewed public interest in racism and imprisonment in the United States, and uprisings against racist police murder have changed the national conversation in recent years, radicalizing many. The flame of resistance that shone from a Birmingham Jail to San Quentin is alight for a new generation.

Berger’s aim here is to educate, agitate and organize. Both these books will be of great interest to activists today, from the movement against mass incarceration and the New Jim Crow to the Black Lives Matter movement, or any other movements that confront white supremacy, structural racism and the carceral state.

November-December 2015—ATC 179