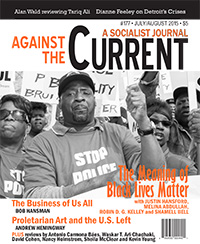

Against the Current, No. 177, July/August 2015

-

Paradoxes of Politics

— The Editors -

Police Violence in the Spotlight

— Malik Miah -

A Majority Black Police Force -- It's Not Enough

— Dianne Feeley -

New Fight to Save Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Brad Duncan -

The Silencing Act and Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Daniel Denvir -

Mass Incarceration for Profit

— Brian Dolinar and James Kilgore -

A Recipe for Killing a School System

— Dianne Feeley -

Detroit's Foreclosure Disaster

— Dianne Feeley -

Albert Woodfox, Gary Tyler

— David Finkel - Black Lives Matter

- Introduction to Black Lives Matter

-

From Ferguson to Baltimore

— Justin Hansford -

The Movement Has a History

— Melina Abdullah -

Moral Appeals Aren't Enough

— Robin D.G. Kelley -

The Black Infinity Complex

— Shamell Bell -

Our Movement Is Global

— an interview with Alice Ragland -

Reflections After Ferguson

— Bob Hansman - Marxism and Art

-

Art and Aesthetics on the Left

— an interview with Andrew Hemingway -

John Reed Clubs and Proletarian Art--Part I

— Andrew Hemingway - Reviews

-

The Prophet Alarmed

— Alan Wald -

Drug War Winners and Losers

— Kevin Young -

A Window on Indigenous Life

— Waskar T. Ari-Chachaki -

Boricua's Revolutionary Inspiration

— Antonio Carmona Báes -

Capital Crimes of Fashion

— Sheila McClear -

Pioneers of Women's Liberation

— Nancy Holmstrom -

Life After Death for Labor?

— David Cohen

Sheila McClear

Stitched Up: The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion

By Tansy E. Hoskins

Pluto Press, 2014, 264 pages, $16.99 paperback (40% off).

IN FEBRUARY 2013, 21-year-old Kayla Phillips — who happened to be Black — bought a bright orange leather bag costing $2,500 by Paris brand Celine. Then things went disastrously wrong.

The woman left the store, but the clerk notified the police. Apparently the clerk believed there was no way that a Black, working-class woman could have the means to buy such a bag legitimately. Undercover officers found her a few blocks away and she was charged with credit card fraud.

Two months later, Trayon Christian, 19, was followed by plainclothes officers outside the same store and accused of fraud after he purchased a $349 Ferragamo belt.

In August 2014, justice, at least, was won: Barney’s agreed to pay to those defendants a combined $525,000 for racial profiling.

In Stitched Up, Tansy E. Hoskins explores fashion through an anti-capitalist lens. She uses these examples to illustrate how fashion can be a flashpoint for racism as well as sweatshop labor, environmental destruction, and unhealthy body image.

In April 2013, a horrific event occurred on a larger scale. Outside Rana Plaza, a building containing garment companies in Dhaka, Bangladesh, workers had argued with their managers about building safety but the managers replied that anyone who didn’t enter would have their wages docked for the month.

Faced with starvation, they took the risk. The building collapsed, resulting in 1,133 deaths and. 2,500 injuries. Buy clothes from Wal-Mart? Mango? Benetton?

Harbison argues that whether speaking of catastrophic factory disasters like Rana, white Western women being driven into debt or 40-year-old Chinese factory workers deemed too old to work, the garment industry remains twisted up with capitalism:

“Fashion is a deregulated, subcontracted, trend-based industry that relies on selling billions of short-life units every season at maximum contract,” she writes. In other words, fashion, whether high or low, revolves around a system of sweatshop labor and snaring women into an endless cycle of desiring and buying the latest styles.

Fashion Statements

Yet fashion can also be a tool in the hands of people who avoid these traps. As Hoskins mentions, in the 1970s disaffected British youth wanted to make a statement to the outside world, so they created a “punk” style of dress, with spikes, Mohawk hairdos, torn clothing and heavy work boots. The look soon travelled to New York, where musicians put their own spin it.

Other examples of bottom-up approaches to fashion include the fight to wear the hijab in France (which has now been banned in schools), and in the late 18th century United States, women’s struggle to wear pants in public.

Interestingly, that fight continues. In 2009, a Sudanese journalist wore pants and was forced to go to trial for her “indecent” act. The judge spared her the requisite 40 lashes but handed down a $200 fine.

Hoskins has no faith in various aid campaigns — unless they include collective organizing. Some are funded by the corporations and frequently backed by celebrities.

She recounts that TOMS gave a pair of shoes to the underprivileged for every pair that a consumer purchased, to great fanfare. While TOMS customers bought quality shoes, the pairs the company gave away to Third World countries were cheap versions, creating a glut of useless shoes that soon fell apart.

Stitched Up, while an accurate overview of the last 100 or so years of the garment and sweatshop industry, goes light on the fact that people want and sometimes need to dress up — for work, for example. Especially for women adornment is unavoidable — dating, socializing, and social status.

Still, Hoskins is right when she writes that as long as the garment industry operates and fashions various accouterments to seduce potential consumers, capitalistic-fashion is here to stay.

July-August 2015, ATC 177