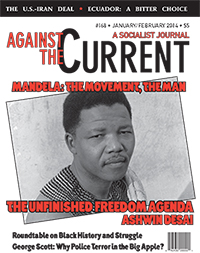

Against the Current, No. 168, January/February 2014

-

Manufacturing Bankruptcy

— The Editors -

Will the Iran Deal Hold?

— David Finkel -

The Invisibility of Fascism in the Postwar United States

— Chris Vials -

A Note on McCarthyism

— David Finkel, for the ATC Editors -

Ecuador's Bitter Choice

— Marc Becker -

Nelson Mandela's Long Walk

— Ashwin Desai -

Much Has Been Said....

— David Finkel - Remembering E.P. Thompson

-

On E.P. Thompson's Legacy

— Sheila Cohen -

Breaking the Grid, Making Our Class

— Manuel Yang - Freedom Struggle

-

Police Terror in the Big Apple

— George Scott -

Civil Rights, Poverty and Capitalism

— Marty Oppenheimer -

Slavery's Harrowing Reality

— Xiomara Santamarina -

Freedom Now Vision Unfinished

— Malik Miah -

Organizing that Changed Mississippi

— Bill Chandler -

Black Workers, Fordism and the UAW

— Dianne Feeley -

"You Can't Kill a Revolution"

— Matthew Garrett -

Making Their Own Freedom

— Robert Caldwell -

A Saga of Revolution

— Derrick Morrison - Reviews

-

A German Lenin?

— Charlie Post - In Memoriam

-

Remembering Steve Kindred (1944-2013)

— Jesse Lemisch -

Come, Let's say good-bye

— Dan La Botz

Dianne Feeley

The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford

By Beth Tompkins Bates

Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012, 344 pages with photographs. Paperback edition forthcoming in February 2014.

THE MAKING OF Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford attempts to map the transition from the Detroit Black community’s idolization of Henry Ford to its support of the UAW’s successful 1941 campaign to represent the workers at Ford. While General Motors, Chrysler, Packard, Briggs and other auto companies were unionized in the 1936-’37 strike wave, Ford maintained its anti-union stance until the eve of World War II through the use of the carrot and the stick.

Beth Tompkins Bates weaves her story of Ford’s success in revolutionizing and dominating auto production with the story of the Great Migration of Blacks from the South to Detroit. By 1920 Detroit was the fourth largest U.S. city — with almost 1.2 million people, half a million more than today — as well as its fourth most important manufacturing center.

While in 1910 there were about 5,800 African Americans living in the city, a decade later there were 41,000; over the following decade that number tripled. At the same time immigration was stalled, first by World War I and then by the 1921 and 1924 restrictive immigration laws.

Bates’ first chapter outlines how Ford’s assembly-line production system required a work force willing to put up with fast-paced, repetitive jobs. In the years before World War I this rigid system led to an annual labor turnover of about 370%. In order to reduce turnover and facilitate continuous production Ford and his executives unveiled a new program at the beginning of 1914. They reduced the work day from nine to eight hours and implemented the Five Dollar Day, Profit-Sharing Plan.

The basic Ford wage was $2.34 a day, about average for the industry, but workers who met standards for “personal cleanliness, sanitation, ‘thrift, honesty, sobriety, better housing, and better living generally’” (24) were eligible for a profit-sharing bonus of $2.66. At that time roughly 75% of Ford workers were immigrants, so attending English class twice a week was part of the deal, with graduation marked by a bizarre “Melting Pot” ceremony in which workers discarded their native costumes and received an American flag along with their diploma.

The second chapter outlines the changing needs of the Ford Motor Company (FMC) and the evolving views of Henry Ford. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, Ford saw a Black work force as less open to radical socialist ideas than foreign-born workers. He paid Blacks a wage equal to whites and initially did not segregate them into the more onerous jobs.

In addition to working on the assembly line, Black men worked as crane operators, purchasers of raw materials, and in the company laboratories or drafting rooms. They were accepted into the apprenticeship program and became skilled electricians or tool-and-dye makers.

Mechanisms of Control

As Ford discarded his molding of an immigrant work force in the post-World War I period, he developed an even more repressive, but similarly paternalistic, plan targeting African-American workers. Determined to combat the rising labor militancy that challenged the open shop, he hired Harry Bennett to direct Ford Motor Company’s Service Department, which was responsible for the surveillance of workers.

Part of the new personnel procedures included hiring recommendations from a select group of Black ministers. This effective strategy, used by the Pullman Company, Chicago meatpackers and steel mill executives in Pittsburgh, tied the Black ministers to the corporation.

For their part, the ministers were happy to refer male parishioners to Ford and accept Henry Ford’s financial contributions. By 1923 Harry Bennett hired Donald J. Marshall, a Black ex-cop, to join his team of spies, reporting on Black workers both on the job and in their community.

Because other plants hired relatively few Blacks, FMC was able to hire Black men who were disproportionately “educated, married and willing to remain at Ford longer than Ford’s white employees.” (62) Paid the same as white men, Black men proved more willing to endure the intensity of the conditions because unlike the whites, they had few alternatives — a fact FMC came to count on.

When Ford open the Rouge foundry in 1920, workers assigned there made a premium. Forced to work in extreme heat, they suffered burn injuries and inhaled nauseous fumes. But when the company faced financial difficulties in 1927 and was forced shut down and retool for six months, the reopening included assigning Blacks disproportionately to the foundry while also eliminating premium pay. As job segregation became the norm, Ford’s wage differential between Black and white workers grew to 11%. In fact the foundry became known as a “black department.” (64)

Nonetheless the wealth from Ford wages was a crucial stimulant to the economic growth of Black Detroit in the 1920s. As early as 1922, African-American men were nearly 26% of the Rouge work force; by 1940 half of all Black men working in the metropolitan area were employed at FMC. In addition to being carefully scrutinized, Black foundry workers were subjected to a higher rate of burn injuries and inhaled nauseous fumes. This resulted in higher death rates, with tuberculosis and pneumonia the number one and number two causes.

The Black Housing Crisis

At the same time Black migration to Detroit was expanding, opportunities for housing were dwindling. Chapters 3-6 focus on the emergence of the 20th century Black community in the 1920s and early ’30s. Unlike the previous century, Detroit became a segregated city through the use of racial covenants. The author remarks:

“White workers may not have had much control over the hiring polices of the FMC and other enterprises, but they could take action to keep their neighborhoods segregated.” (105)

The Detroit Real Estate Board codified this practice in 1924 by adopting Article 34, which stated:

“A realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood…members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” (105)

By the summer of 1925 white mobs of more than a thousand — some of them armed — attacked the homes of several well-off African Americans who ignored these covenants and moved into better-off neighborhoods.

Mobs smashed the windows of Dr. Alexander Turner, head of Dunbar Memorial Hospital, shot at Vollington Bristols’ home, attacked John Fletcher and his family and threw rocks at Dr. Ossian Sweet’s home.

According to contemporary accounts all but Dr. Turner armed themselves; their friends and relatives mobilized to defend their homes. Of course the police, heavily recruited to the Ku Klux Klan, took the side of the mobs. Over the course of the summer the police shot 55 Blacks. That summer too, the KKK — pledged to keep Blacks confined to segregated areas of the city — held a rally attended by more than 10,000.

Given the racism of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the reality of labor’s weakness in an open-shop city, Black Detroiters did not look to unions to assert their rights either at work or in their communities, but to Black institutions that were critical of unions’ exclusionary practices. Having fled the Jim Crow South, they found themselves confronted by a new racial code.

During this period African Americans joined together in a variety of organizations — from the NAACP to the Urban League on the more conservative end of the spectrum. to the Good Citizenship League and the Garveyite Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) on the progressive side — to fight for their rights. These included church groups, women’s clubs, Black veterans’ groups, community organizations, the Nation of Islam and political clubs.

As early as 1922 the UNIA had a membership estimated at 5,000, with a strong base of industrial workers and women. Some of its meetings and marches were attended by as many as 15,000. It purchased a building for its meetings, put out a weekly newspaper, the Detroit Contender, and established drugstores, restaurants, theaters, laundries, shoe shine parlors and even a gas station to provide an infrastructure to meet the needs of Blacks in a segregated city.

Interestingly, Bates points out that after Garvey was imprisoned and deported, key members such as Charles C. Diggs, owner of a funeral parlor close to the UNIA building, and Joseph Craigen, an autoworker, redirected their energy to building an alternative to the Republican Party — eventually leading to the formation of Black Democratic Clubs.

Building Alliances and Coalitions

The thesis of The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford is that the experience Black Detroit gained through their fight for social justice and their decisions about which politicians would be trustworthy allies gave them valuable experience in coalition work with whites.

Chapters 3-6 discuss the variety of experiences the community had as they fought against racial profiling — particularly encountering the police department and the criminal justice system — and racial covenants at a time when the Klan was burning crosses.

In 1925 Dr. Ossian Sweet and his family were arrested when someone in the house shot two white men in the rock-throwing crowd, killing one. Two trials followed, the first ending in a hung jury, the second ending in an acquittal. The judge in both cases, Frank Murphy, ran for mayor in 1930 after the Klan-backed Mayor Bowles (elected on his third try) proved so incompetent that he was recalled.

Murphy’s two-week campaign was based on an intense populism. During that period he spoke at several Black churches, won 80% of the vote in Black precincts. Once in office, Murphy formed the Mayor’s Unemployment Committee to coordinate the city’s relief effort. The Colored Advisory Committee, chaired by John Dancy, head of the Detroit Urban League, was in charge of monitoring the city’s programs to make sure there was no discrimination.

By 1932 Murphy’s support for the election of Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) helped to establish the close connection between the Black community and the Democratic Party. The author also sees this shift from the Republican to the Democratic Party as representing “a loosening of Ford’s grip over black Detroit.” (180)

So too the Communist Party became known and respected for its role in the International Labor Defense-led campaign to defend nine young Blacks accused of rape (the Scottsboro case, 1931).

Prominent Detroit Blacks followed the political tussle over whether the ILD or the NAACP would represent the defendants; they generally sided with the more militant ILD. Black Communists would become important in the next phase of the Black community’s decision on how to respond to the Depression.

Why Join the UAW?

In 1930 there were 24 national and international unions, 10 of which were affiliated with the AFL, with a “whites only” policy. How would FDR’s National Recovery Administration operate to put millions back to work at a living wage? While FDR insisted that the wage code outlined in the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was colorblind, the Black community debated the problem: If there was no wage differential, wouldn’t employers simply replace African Americans with white workers?

But by 1933 National Urban League Convention concluded that the “cause of the Negro worker” could not be considered “without recognizing the importance of collective bargaining.” (190)

That same year, the Civic Rights Committee was founded, headed up by the dynamic and militant postal worker Snow Grigsby. Initially CRC’s goal was to put pressure on city officials to hire more African Americans.

Bates sees the CRC as introducing “a new style of protest politics,” spurring on other organizations and taking a lead when necessary for “the betterment of black Detroit.” (195, 196) These discussions and actions moved Detroit’s African Americans from the Black nationalist approach of the 1920s to a united front against discrimination approach during the Depression.

The author concludes Chapter 7 by remarking that while historian Harvard Sitkoff argues Black America “received no new deal from the first Roosevelt Administration,” this did not stop Black Detroiters from beginning a process that would challenge “the very structures shaping the racial status quo.” (198)

Chapter 8 begins by outlining a three-part process through which the Civil Rights Committee broadened its base to build a closer relationship with organized labor. By 1935 the CRC launched a local chapter of the National Negro Congress (NNC) and the two worked closely together to promote “a labor-oriented, civil rights agenda.”

As the organizations were making demands to end discrimination in the private sector, they reached out to the newly formed UAW-CIO. But given the recession, Black workers were happy to have a job and didn’t necessarily see that membership in the UAW-CIO would benefit them.

During the sitdowns at Kelsey Hayes, GM and Chrysler in the winter of 1936-‘37, while some Black workers joined the union and participated in the sitdown, according to NAACP assistant secretary Roy Wilkins, the majority stood back, wondering whether the UAW would defend their access to better jobs. They also studied the union’s internal practices. Would they be treated equally at UAW socials, whether dances, picnics or bowling teams?

Beginning in 1936 the National Negro Congress focused on helping the UAW organize Black workers. Essential for success, the NNC argued, was hiring Black organizers. By April 1937 UAW President Homer Martin hired Paul Silas Kirk, a Black crane operator who had become recording secretary of his local. By the fall there were two additional organizers, three part-timers and a UAW Subcommittee for Organization of Negro Workers with an African-American woman assisting with research and publicity.

Bennett’s Gangsters

Bates cites the figure of 3,000 “street fighters, underworld characters, and athletes” under Harry Bennett’s control. These included African Americans such as ex-cop Donald Marshall and Willis Ware, former Michigan track and football star.

Working with the Dearborn Police, Bennett unleashed an attack against unemployed workers marching for jobs, killing five, one of whom was Black. The attack on the 1932 Hunger March was repeated five years later when UAW leaders attempted to leaflet workers during shift change — and has gone down in labor history as the Battle of the Overpass.

By 1937 the UAW became embroiled in a faction fight between the Homer Martin and more radical caucuses, one led by George Addes, associated with the CP, and the other by Walter Reuther, whose base included both Socialist Party members and more conservative Catholic trade unionists.

Bates sees this internal struggle, which put organizing at Ford on ice, not just as a waiting period, but as building, through the CRC-NNC alliance, more self-confidence and organization within Detroit’s Black community. Between 1937 and 1941 about 4,000 Ford workers were fired for suspected union activity. Thus any attempt to organize the thousands of Black Ford workers meant having Black UAW organizers meeting with them secretly.

Changing the Union

With the overthrow of Martin in early 1939, Black UAW delegates came with a list of demands to the reorganized UAW’s convention. In addition to hiring Black organizers, they demanded giving Black women the right to apply for jobs both inside the union and on the production line, fighting for Blacks to have equal access to apprenticeships, opportunities for promotion and advancement, establishing a department to monitor the problems minority workers faced and electing at least one Black to the International Executive Board. (233)

While the new leadership was willing to hire Black organizers as permanent staff, several organizers were frustrated by the reality that although white union officials recognized there was discrimination, they had a “go slow” attitude because they did not want to lose the loyalty of white autoworkers, particularly southerners with racist views. And given the recession in 1937-38, UAW membership had taken a dive. Of the 200,000 GM workers, by May 1939 only 12,000 were paying dues.

Perhaps even more challenging was a labor dispute at Chrysler in the fall of 1939. Dodge Main management locked out 24,000 workers, including 1,700 African Americans, and the UAW struck all of Chrysler’s factories in retaliation. After several weeks the corporation organized a back-to-work movement aimed at Black workers. Bates highlights this moment as proof that they saw sticking with the union a successful strategy for their community.

Rev. Charles Hill, head of the CRC and the NNC’s Trade Union Committee, explained to Michael Widman, a CIO official sent in from the United Mine Workers Union to relaunch an organizing drive at Ford Motor Company, that there must be different tactics the second time around: The UAW had to reach out to Black workers.

Widman was open to this approach and willing to listen to the volunteer organizers who were working through the NNC. Some were members of the Communist Party; others were comfortable working with them. These included Walter Hardin (CP), William Nowell (CP), Shelton Tappes, Veal Clough (former Sleeping Car Porter), David Moore (CP), Paul Kirk (CP), Joseph Billups (CP), Percy Llewellyn, Norman Smith, Nelson Davis, Coleman Young, William Johnson, Arthur McPhaul, Horace Sheffield, Percy Keyes and Christopher Alston (CP, father was a Garvey supporter and socialist).

Most importantly, by January 1941 Billups, Tappes and Clough — all on the UAW-CIO payroll — were able to build a grassroots steward system within the Ford foundry. They initiated quick actions on the shop floor including a sit-in that demanded everyone in the foundry earn ninety-five cents an hour. Tappes claimed that winning this demand raised the wages of almost half of the foundry workers.

When Harry Bennett fired eight workers in the rolling mill on April 1, thousands of workers moved through the Rouge complex and shut it down in a wildcat. The next day the UAW leadership authorized the strike. At this point 14,000-16,000 African Americans worked at Ford, constituting about half of all of Detroit’s Black male wage earners. The author states: “Most of the black workers who walked and joined the whites on the picket lines outside the factory were veterans from the foundry and did not return until after the strike.” (245)

Those who remained had only been hired a month or two earlier. But on April 4, Rev. Charles Hill, Rev. Horace White and Rev. Malcolm Dade, along with John Dancy and Horace Sheffield of the NAACP’s Youth Council, appealed to them to leave the plant — and after the UAW assured their safety, over 1,000 Black workers left.

For the author, the organizing of Ford foundry workers, plus the April 4th walkout, signaled that Black autoworkers were willing to give the UAW a chance to represent them. They could commit to doing that because the backbreaking and repressive policies at Ford propelled them to consider the option of uniting with white workers.

Bates sees the role of Black organizers as the linchpin in this process. And the May 1941 the Ford-UAW contract contained an important anti-discrimination clause, the handiwork of Shelton Tappes. It was approved.

Revisiting the Strike

While I found The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford a compelling story, it did cause me to go back and reread Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW by August Meier and Elliott Rudwick. Bates cites Black Detroit throughout her story, and challenges its more pessimistic account of the alliance forged between Black and white workers.

Meier and Rudwick offer a more detailed account of the strike. While workers walked out on April 1st, they point out that the following day about 300 whites — mostly working in Ford’s Service Department — and 1,500-2,500 Black workers crossed the picket lines. Armed with steel bars and knives, they were sent out to launch attacks against strikers. Meier and Rudwick note, quoting the News:

“Both times the attackers, mainly black, were repulsed by the pickets.” Organizer John Conyers was among the unionists seriously injured in the violence, yet the fact that at this stage only small numbers of blacks were among the thousands on the picket line reinforced the tendency to perceive these clashes as racial conflicts which might erupt into a race riot.” (89)

Seeing Ford’s tactics as an attempt “to encourage a back-to-work movement,” similar to what Chrysler management had in mind when they attempted to use Black workers as scabs, UAW officials sought and received statements of support from Black leaders.

That Sunday the NAACP Youth Council and adult branch distributed 10,000 “Don’t be a strikebreaker” leaflets at churches. The UAW also prepared special radio broadcasts and issues of their newspaper, Ford Facts, aimed at Black Ford workers and their families; they were careful to blame the company for the assaults on the picket line.

As a result, Meier and Rudwick echoed the assessment in The UAW and Walter Reuther that this strategy “’won the hesitant neutrality of Ford Negro workers, which was enough to ensure the success of the strike.’” (102)

They also concluded that the UAW contract, which passed two months later by a 70% vote, did so without the votes of the majority of Black workers. However, they point out that once the contract passed, the vast majority came to support the union. Those who were in the better jobs didn’t lose them, as management had predicted. And most were impressed by Shelton Tappes’ ability to negotiate the contract’s anti-discrimination clause.

While Bates proposes that Black workers supported the contract and ends her narrative with its passage, Meier and Rudwick’s account ends two years later. This enables the authors to evaluate the UAW’s promises.

Despite some upgrading of jobs under the UAW contract, Black autoworkers were more likely to be laid off in the transition to war production. The authors also cite the mixed role UAW officials played in confronting white “hate strikes” as Black men were beginning to advance and Black women hired for production.

I think Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW still offers a more realistic view of the tensions that existed within the union. It also explains the need for the establishment of the Trade Union Leadership Conference in the 1950s and the rise of the Detroit Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) in the late 1960s. The fact of the matter is that the corporations — particularly GM — and much of Walter Reuther’s base didn’t want Black workers to advance, particularly into skilled trades.

The strength of The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford is that it highlights the role Black organizers played in the UAW drive at Ford. Bates shows how for organizers like Shelton Tappes, Veal Clough and Chris Alston, the union was to serve as the basis for building civil rights for the entire Black community. Certainly that was in the tradition of the CRC, NNC and even the social gospel ideology that a growing number of ministers adopted.

Even if the UAW was timid in taking on the company and educating its base, unionization represented the new floor upon which generations of Black families were to stand.

January/February 2014, ATC 168