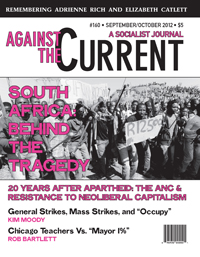

Against the Current, No. 160, September/October 2012

-

Supreme Court Storm Clouds

— The Editors -

Notes in Memoriam

— The Editors -

Why Race Matters in the 2012 Elections

— Malik Miah -

Health Care Reform or Ruin?

— Milton Fisk -

Chicago Teachers' Strike Looms

— Rob Bartlett -

The Green Party Campaign

— Michael Rubin and Linda Thompson -

General Strikes, Mass Strikes

— Kim Moody -

Letter to the Editors

— Clifford J. Straehley, M.D. - South Africa After Apartheid

-

The Left and South Africa's Crisis

— an interview with Brian Ashley -

Social Movements in South Africa

— Zachary Levenson -

The Brutal Tragedy at Marikana

— Amandla! -

A "Tunisia Moment" Coming?

— Niall Reddy -

Further on Marikana Miners

— David Finkel, for the ATC Editors - Culture and Politcs

-

The SP's Roots and Legacy: In the American Grain

— Benjamin Balthaser -

American Poetry's "Labor Problem"

— Sarah Ehlers -

A Bend in the Labyrinth

— Alan Wald -

Mapping the African-American Literary Left

— Konstantina M. Karageorgos -

The Common Language of Adrienne Rich

— Julie R. Enszer -

The Life and Memory of Elizabeth Catlett

— Kelli Morgan -

Faruq Z. Bey, 1942-2012

— Kim D. Hunter - Reviews

-

SWP: Long March to Oblivion

— David Finkel -

Invaluable History and Important Lessons

— Malik Miah

Milton Fisk

FAR FROM LAYING the health care debate to rest, the June 28 Supreme Court decision on Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA) put life back into it. Calling the individual health insurance mandate a “tax” aroused anger on the right, but the court’s ruling on federal Medicaid money is what really puts a new dimension into the fight.

The Court ruled that the federal government cannot deny a state all its Medicaid money for refusing only that part earmarked for expanding the program. That means a state governor can now risk less politically by refusing federal money to cover those at 100-133% of poverty-level, while federal money for those below 100% would still flow into the state.

Conservative state governors are now the frontline of the attack on expanding public payment for health care.

The fuss over Medicaid is not just an outbreak of a bad case of states’ rights. Behind it lies a national agenda of privatizing still more parts of the U.S. health care system. Medicaid expansion of ACA runs counter to that agenda. It puts more people into systems of state insurance in two ways — increasing Medicaid eligibility by making it available to those at 100-133% the poverty rate, and making Medicaid available to the many below the poverty line whom states now exclude from coverage.

Taking these two together, some 16 million uninsured who live below 133% of the poverty line will be added to government programs.

The Privatizers’ Plan

At the federal level, the Court’s decision to allow the “individual mandate” for buying health insurance has complicated the right-wing effort. For example, insurers and providers for those at 133-400% the poverty rate must follow rules for the insurance exchanges, which will be set up to create tightly controlled markets for insurers, which privatizers normally dislike.

But because large numbers of citizens consider the individual mandate a denial of freedom, the opposition to government payment for health care joins with the opposition to government regulation of private insurers. This free-enterprise front hopes to replace the ACA by spreading opposition to both the ACA’s expansion of government insurance (Medicaid) and regulation of private insurance.

This aggressive front’s objective is to replace the ACA with a free-enterprise plan. It appeals for broader support by claiming that its plans would halt the ever-increasing cost of the current U.S. health care system, while also increasing the availability of health care. Reducing demand for health care, however, is the driving principle of the plans the privatizers have unveiled.

Representative and now Vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan of Wisconsin has proposed replacing Medicare with a voucher system. A senior would receive a fixed amount of money from the government to buy a private insurance plan. The federal contribution to a state’s Medicaid fund would become a block grant, leaving the state free to decide how to use it. Finally, employers would get tax breaks for helping pay for employee health insurance.

An even more ambitious plan, summarized approvingly by New York Times columnist David Brooks, would employ tax credits to defray the cost of private insurance. (The credits would phase out for the rich.) Employers might lighten their health insurance burden by merely supplementing these credits for their employees. Those on Medicare and Medicaid would also switch to using tax credits.

If health care inflation threatened, the remedy would not be to increase the sources of the supply of health care, but to reduce tax credits — thereby reducing demand. While the prosperous could use their own money to buy additional insurance, the less prosperous might end up with inadequate care. In that case, struggles around health care would predictably return.

Changes from Right and Left

Obama’s ACA, being thoroughly eclectic, offers different programs for different segments of the population. The state insurance model applies to those in poverty or just above the poverty line (up to 133% of poverty), but a federal subsidy model applies to those at the lower end of the middle class (at 133-400% of the poverty rate).

Whether the ACA’s expansion of health care ultimately leads to more privatization or stronger public financing depends on an ongoing political struggle. The act points in contradictory directions.

Subsidies on a sliding scale of income facilitate the purchase of health insurance. These insurance exchanges direct people in the lower income range toward a private plan.

Obama tried unsuccessfully to insert a “public option” along with private insurance plans, but it didn’t survive the opposition of those for whom the whole point was to privatize. Ironically then, a feature of what applies to a segment of the population in the ACA has become its rightwing critics’ model for all health insurance!

At the same time, some left critics of the ACA envision using the state insurance exchanges as a mechanism to put in place state single-payer systems.

Since a state should be able to make decisions for its own exchange, Vermont is applying for, and should be able to receive, a waiver allowing it to include a public system in its exchange, taking effect in 2017. With less overhead, a public system could win out in competition with the private systems. If this happened in enough states, the various states could integrate their plans into a national single payer system — as happened in Canada in the early 1970s.

On the other hand, as a New York Times editorial (July 29, 2012) notes: “The Congressional Budget Office predicted that states with a large number of poor people would not expand their Medicaid programs…By 2022, the budget office predicts, only two-thirds of those who would become eligible for Medicaid if all states expanded to the levels sought by the reform law will actually gain eligibility.”

According the CBO estimate, that would leave three million more people uninsured by 2022. A study by Harvard School of Public Health researchers, comparing states that have previously expanded their coverage of childless or disabled adults with neighboring states that haven’t done so, showed significant reductions in death rates and “brought a 21 percent reduction in cost-related delays in getting care.”

Cost Spiral: Who’s to Blame?

A major reason given for bemoaning privatizing in health care is that private insurers raise the cost of their premiums beyond what can be justified, depriving the society of funds needed for other things, like education and housing. The problem, though, is much broader.

Let’s consider the insurer’s interactions with doctors, hospitals, plan managers, drug makers and producers of medical devices. Insurers are enablers of rich returns for all of these providers, while raising their own premiums (to attract investors in the financial markets). So the insurance market “works” by mutually ratcheting up the providers’ charges and the insurers’ premiums.

The ACA sets a limit on how small the ratio of actual medical costs to premiums can be. But such a limit does not stop the ratcheting up of prices. If a hike in premiums threatens to drop below the limit, providers will charge more for health care — not to avoid breaking the limit but simply because they benefit.

Likewise, if providers’ costs increase, insurers will raise premiums to match the increase. At best, limiting the costs-to-premiums ratio can only slow the rate of health care inflation.

The contrast with a single payer system is striking. The latter would not be a for-profit insurer with an incentive to ratchet up premiums. Providers, even if they might be for-profit, could not play mutual ratcheting-up games.

One may question the relevance of the public areas remaining in the ACA. Indeed, what does it mean to be a patient in a public health insurance system? He or she may be under the care of doctors who belong to a private physicians’ company, in a room in a private hospital, getting bills through a publicly traded Medicare management group, on a drug coming from a major multinational pharmaceutical, and undergoing knee replacement with a device made by a division of Johnson & Johnson.

Struggle Continues

What is the best we can do to justify saving the public areas in the ACA? Is it only that in some sense Medicare and Medicaid set limits on profiteering? The crowd of private actors compromises even these limits.

All this is true; but the weakness of ACA’s limits on privatization should be a call to resist and to extend the application as elastically as possible.

In the face of onslaughts from the political right, I believe it is important to support the ACA critically. Failure to fight against privatization of Medicare and Medicaid demanded by the right wing will lead to even more people being unable to afford care. There is no virtue in permitting a disaster just to prove we were right about its coming. If the 2013 Congress repeals the ACA, the items in it that protect against privatization will go down with it.

When the Congress debated the ACA, it needed assurances that there would be new income to pay for insuring more people. So it put a tax on hospitals, drug manufacturers, and medical device makers, all of whom would be selling more to meet the needs of the 32 million previously uninsured people getting free or subsidized insurance.

In drafts of the bill, device makers were to pay a 4% tax on sales; they protested and it was reduced to 2.3% in the final version. Now they want to renege on that deal, falsely arguing that a tax will send production abroad and consequently innovation would slow down.

Actually, the ACA requires that those devices made abroad and shipped back to the United States for sale will be subject to the tax, while devices made here that are shipped abroad for sale will not. Further, with more people insured there will be more money available for innovation.

At this moment, the practical need is to head off efforts to turn all the health care system over to profit making. Once entrenched as a completely privatized system, it would make the struggle to build a single payer system even more difficult. The battle to make the private companies — like the device makers — who profit from the health care system to help pay by is another instance of a battle ahead.

September/October 2012, ATC 160

obama’s giveaway to the insurance industry was, in fact, worse than nothing – see http://www.pnhp.org/news/2010/march/pro-single-payer-doctors-health-bill-leaves-23-million-uninsured

Physicians for a national health plan has the most comprehensive analysis, and in fact had the courage to oppose the bill.

no one needs health insurance – everyone needs health care