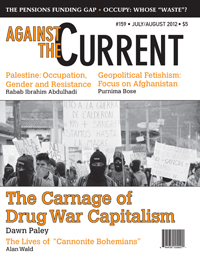

Against the Current, No. 159, July/August 2012

-

Swing of the Pendulum?

— The Editors -

Immigrant Youth Victory!

— The Editors -

Rolling Back Reconstruction

— Malik Miah -

The Pensions Funding Gap

— Jack Rasmus -

The Media's Dirty War on Occupy

— Jacob Greene -

"Authoritarian Populism" and the Wisconsin Recall

— Connor Donegan -

Marching for Life, Water, Dignity

— Marc Becker -

Geopolitical Fetishism and the Case of Afghanistan

— Purnima Bose -

Living Under Occupation

— Rabab Ibrahim Abdulhadi - Samiha Khalil (1923-1999), Resistance Organizer

-

Drug War Capitalism

— Dawn Paley -

Cannonite Bohemians After World War II

— Alan Wald -

Why Music Must Be Revolutionary -- and How It Can Be

— Fred Ho - Reviews

-

Letter on Trayvon Martin

— Christina Reseigh -

Soldiers of Solidarity

— Mike Parker -

Organizing Is About People

— Carl Finamore -

An Unfinished Revolution

— Derrick Morrison -

The Black Panthers in Portland

— Kristian Williams

Connor Donegan

ON MAY 5th, roughly 1,334,450 people voted in favor of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker and his program of union busting, austerity, corporate tax cuts and property-tax freezes, while 1,162,785, voted to recall the governor mid-way through his term. Walker’s victory will be seized on by the Right as they drum up support for copycat union-busting bills, while Walker himself has reinforced his “mandate” to “make tough decisions.”

Last year has been heralded as a year of “dreaming dangerously,”1 as mass movements and rebellions reasserted themselves as complex, unpredictable and very real historic forces. In Wisconsin, tens of thousands of people participated in a fight with the legislature to protect the rights of public sector workers to collective bargaining and to protect public services like education and the state health insurance program from severe budget cuts.

By directing the statewide movement into recall elections, Wisconsin progressives chose a battle on ground that the Republican Party has been preparing for decades. There was no “over-reach” of power, as many insisted at the time, but instead, forward movement of a political program that always sought to overturn the status quo.

While the conservative candidate had much to show for himself, the Democratic Party had no alternative to offer, let alone a compelling one, but progressives had no other political organ to carry through their demands. And, of course, many remain loyal supporters of the Party in any case.

Progressives need to understand why Walker won. Blaming Citizen’s United does not cut it, not even close. The roots of the successful Republican strategy in Wisconsin go back to the years of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, right-wing leaders in the United States and Britain who sought unabashedly to destroy working class power.

They blamed the economic crisis (“stagflation”) on unions. They scapegoated people of color and offered reassurance to middle-income whites by promising social discipline, building on the “law and order” platforms of the 1970s, while whipping up anxiety and resentment over the social movements of the 1960s and early ‘70s.

In short, they consolidated their own electoral base while attacking the very basis of working class power not only through union busting and economic deregulation but also through carefully crafted ideological battles that discredited unions and trumpeted individualism.

As Alan Budd, a key economic advisor to Thatcher stated,

“My worry is . . . that there may have been people making the actual policy decisions . . . who never believed for a moment that this was the correct way to bring down inflation. They did, however, see that it would be a very, very good way to raise unemployment, and raising unemployment was an extremely desirable way of reducing the strength of the working classes — if you like, that what was engineered there in Marxist terms was a crisis of capitalism which recreated a reserve army of labour and has allowed the capitalists to make high profits ever since.

“The crisis for the Left was not due mainly to the fact that elites decided to take the offensive, but that these politicians won elections and re-elections. The Right successfully melded an elite, capitalist-class political program to the anxieties, frustrations, identities, and political imaginations of millions of workers, professionals, and small business owners. They fancied themselves freedom fighters willing to stand up to the ‘Big Labor Bosses’ and the ‘Welfare Queens.’”

Of course, not everyone was content with this “authoritarian populism,” as the British cultural critic Stuart Hall aptly called it. But Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition was the last time that progressives would be allowed to organize independently inside the Democratic Party. Rather than create a progressive vision for society that would energize its base, the Democratic Party decided it would be far safer to pander to the middle and has since been continually “dragged” to the Right by the more ambitious Republican Party.

Today’s Republican Party strategy is a hyper-charged repeat of the Reagan years. The New Right thrives in crisis situations, since crises provide ammunition for the war against the status quo, always skirting the fact that they themselves are at the direct service of the financiers and corporate executives — the real parasites. In 2008, capitalism nearly came crashing down on top of us and neoliberalism, so we thought, no longer looked so appealing.

The Right’s Opportunity

The Right took the crisis and ran with it, turning it into a grand opportunity. Wisconsin provides a case in point. Progressives exclaim, not without reason, that Walker’s legislation negatively effected just about every group of people in the state — through cuts to education, restricting eligibility to Badger Care (state health insurance for low-income residents), effectively barring undocumented immigrants from attending university by charging out of state tuition, disfranchising thousands of voters without state-issued I.D.’s, and busting unions.

Another look at the legislation shows that the Republicans provided material incentives to each key group of supporters, while cultivating and harnessing to their program the real fears and anxieties that have been generated by economic insecurity. While Walker’s support is tilted towards higher-earners, exit polls show that 44% of voters with a 2011 family income below $50,000 voted for Walker.

One heard over and over the complaint that public sector workers are “privileged” and “sheltered” from the pain that everyone else is suffering. As obvious and dubious as this little trick is — pitting workers against each other instead of against the super-wealthy — it did its job.

The multinational corporations who wrote the legislation have thrown the blame for the crisis of capitalism onto the working class by re-scripting it as a budget crisis caused by “Big Labor” and Big Government spending. It was always clear that this legislation advanced a national anti-labor agenda that seeks to destroy the last remaining island of union density in the American economy and over-turn federal labor law. It’s well on its way.

By breaking the unions, they strengthened the power of government administrators who can now dictate terms of employment, benefits, and workplace rules. Thus the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) national strategy was articulated to local governments’ immediate interests, even while gutting their funding. Mandating a freeze on local property taxes may sound like big government coercion, but I suspect a lot of property owners, not just stingy Tea Partiers, are happy to take the money.

Walker eliminated taxes for manufacturers and agricultural producers in Wisconsin. Moreover, the state has already begun giving millions of dollars in tax credits to manufacturers and developers to pay for doing businesses in Wisconsin. Now small business owners and other industries are waiting for their break too. However facile this is as an agenda for jobs or economic security, it is nonetheless a decisive action that looks like an effort to keep jobs in Wisconsin. Workers who fear more plant closings and run-away factories, and those who have been convinced that, in a world scarce of jobs, their well-being is dependent on their employer’s profits may see these action as “common sense.”

As for the Democratic Party, their agenda was far less ambitious, if they even had one. Barrett was at least in principle against ending collective bargaining for public sector workers and pledged an honest effort to restore their rights. He campaigned to “end the ideological civil war” started by Walker. His plan for reconciliation consisted mostly of public workers reconciling themselves to the new normal of austerity and sacrifice.

Wisconsin progressives made two fatal errors. They greatly underestimated the Republican Party, believing that progressives held the majority and that Walker’s only real supporters were billionaires and Tea Partiers. Worse still, progressives misunderstood the longstanding purpose of the Democratic Party in American politics.

Rather than a political platform built to give voice to our daily frustrations with structural unemployment, exploitation and indignity at work, mass incarceration, extreme inequality, endless war, and corporate political rule the Democratic Party effectively neutralizes our anger while advancing the very policies we abhor.

This does not mean that progressives need to leave the entire electoral stage open to the Right. It does mean, however, that if we’re going to be successful we first have a lot of groundwork to do. Here’s a suggestion from Doug Henwood:

“Suppose instead [of the recall] that the unions had supported a popular campaign—media, door knocking, phone calling—to agitate, educate, and organize on the importance of the labor movement to the maintenance of living standards? If they’d made an argument, broadly and repeatedly, that Walker’s agenda was an attack on the wages and benefits of the majority of the population? That it was designed to remove organized opposition to the power of right-wing money in politics? That would have been more fruitful than this major defeat.”2

First thing’s first: progressives and labor unions have to abandon their unconditional support for the Democratic Party. They need us much more than we need them.

Notes

- 1. Slavoj Zizek, The Year of Dreaming Dangerously. New York: Verso, 2008.

back to text - 2. Doug Henwood, “Walker’s victory, un-sugar-coated,” LBO News from Doug Henwood. Lbo-news.com/

back to text

July/August 2012 (web only, not in ATC 159)

First published online at Monthly Review’s Webzine at http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2012/donegan090612.html.