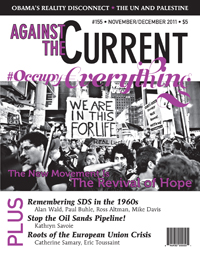

Against the Current, No. 155, November/December 2011

-

Three Years After "Yes We Can"

— The ATC Editors -

The Obama Reality Disconnect

— Malik Miah -

Stop the Keystone XL Pipeline!

— Kathryn Savoie -

Big Three Auto Contracts: Lowlights of 2011

— Dianne Feeley -

Dollarization, Democracy & Daily Life in Zimbabwe

— K.D. -

The UN & the Future of Palestine

— David Finkel -

The Boomerang Is Almost Home

— Jimmy Johnson -

Crisis in the EU: From the Periphery to the Center

— Catherine Samary -

Has Europe's Crisis Peaked Yet?

— an interview with Eric Toussaint - Bolivia's Growing Crisis

-

On Troy Davis

— Theresa El-Amin - Remembering SDS

-

A Theater for the Poor

— Alan Wald -

Memories of [my] Syndicalism

— Paul Buhle -

In Memory of Carl Oglesby

— Ross Altman -

Carl Oglesby: A Mentor & Leader

— Mike Davis - Reviews

-

Bolivia's Uncertain Revolution

— Dawn Paley -

A Revolution's Heritage

— Marc Becker -

A Family, A Tragedy, A Movement

— Karin Baker -

Class & Race in A Modern Catastrophe: Lessons of Katrina

— Derrick Morrison -

Looking North for Labor Revival?

— Barry Eidlin - Dialogue

-

Wrestling with Ellison

— Paul M. Heideman -

History, Theory, Politics & Invisible Man

— Nathaniel Mills

an interview with Eric Toussaint

[THE FOLLOWING DISCUSSION with Eric Toussaint, president of the Committee for Abolition of Third World Debt (CADTM) in Belgium, conducted on September 24, is the sixth installment of a multi-part interview that appears in full on the organization’s website www.cadtm.org. This interview was translated by Christine Pagnoulle and Vicki Briault in collaboration with Judith Harris.]

CADTM: In July-September 2011 the stock markets were again shaken at the international level. The crisis has become deeper in the European Union, particularly with respect to debts. Has the crisis peaked yet?

Eric Toussaint: The crisis is far from over. Even if we only consider the financial aspects, we must be aware that private banks have continued to play an extremely dangerous game which profits them as long as nothing goes wrong, but which is prejudicial to the majority of the population. The amount of bad assets on their balance-sheets is enormous.

If we look at only the top 90 European banks, the fact is that over the coming two years, they will have to refinance debts to the tune of an astronomical 5,400 billion euros. That represents 45% of the wealth produced annually in the EU. The risks are colossal and the policies adopted by the European Central Bank (ECB), the European Commission (EC) and the member States of the EU will not solve anything — indeed, quite the contrary.

European banks finance a significant part of their operations by making short-term loans in dollars from the North American lenders known as “U.S. money market funds” at a lower rate than the ECB’s. Furthermore, to return to the case of Greece, how could the European banks possibly settle for 0.35% over three months if they had to borrow from the ECB at 1%?

They have always financed their loans to European states and companies using loans they themselves took out from the U.S. money market funds — and they continue to do so. Now those money market funds were scared by what was happening in Europe and also by the dispute over the U.S. public debt between Republicans and Democrats.

So by June 2011, that source of low-interest finance had just about dried up, which has hurt major French banks most. This precipitated the tumble they took on the Stock Exchange, and led to the increase of pressure on the ECB to buy back their bonds and thus provide them with new money.

In short, this demonstrates the extent of the domino effect between the economies of the USA and the EU. It further explains the continual contact between Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, the ECB, the IMF — and the major banks from Goldman Sachs to BNP Paribas and the Deutsche Bank. A breakdown in the flow of dollar-loans to European banks could cause a very serious crisis in the Old World, just as difficulties encountered by European banks in repaying their U.S. lenders could trigger off a new crisis on Wall Street.

Since 2007-2008, banks and other institutional investors have displaced their speculative activities from the property market (where they had created a bubble which burst in nearly a dozen countries, including the USA) to the public debt market, the currency market (where the equivalent of U.S. $4,000 billion changes hands every day, 99% purely for speculative purposes) and the primary resources market (petroleum, gas, minerals, food commodities).

These new bubbles can burst at any moment. A possible trigger could be if the U.S. Federal Reserve decided to raise interest rates (followed by the ECB, the Bank of England, etc.). In this respect, in August 2011 the Fed announced its intention to maintain its base rate near zero until 2013. However, other events could trigger a new bank crisis or a crash on the Stock Exchange. The events of July-August 2011 show us it is time to muster our energy in order to prevent the private financial institutions from doing any further damage.

The extent of the crisis is also determined by the volume of the U.S. public debt and the way it is financed in Europe. European bankers hold more than 80% of the total debt of an array of European Union countries in difficulty such as Greece, Ireland, Portugal, the Eastern European countries, Spain and Italy.

In volume, Italian public debt paper amounts to 1,500 billion euros, more than twice the combined public debt of Greece, Ireland and Portugal. Spain’s public debt comes up to 700 billion euros, i.e. about half of Italy’s. The arithmetic is simple: the public debts of Spain and Italy added together represent three times the sum of those of Greece, Ireland and Portugal.

Government and Private Debt

As we saw in July-August, while each country continued to pay off its debts, several banks almost collapsed. The ECB had to intervene. The financial scaffolding of the European banks is so fragile that an attack through the Stock Exchange is enough to bring them down — not to mention what would happen if the Stock Exchange crashed, which cannot be ruled out.

So far, with the exception of Greece, Ireland and Portugal, the states have managed to refinance their debts by taking out new loans as the borrowed capital fell due. The situation has worsened significantly over the last few months. By July/early August 2011, the interest rates demanded by the institutional investors to enable Italy and Spain to refinance their public debt as it fell due with 10-year loans had virtually exploded to reach 6%.

Once again, the ECB had to intervene, buying up massive amounts of Spanish and Italian debt paper to satisfy the bankers and other institutional investors and bring down interest rates. For how long, though? Italy will have to borrow about 300 billion euros between August 2011 and July 2012, as that is how much they will require to honor bonds that fall due over that short period.

Spain’s needs will be considerably lower, at about 80 billion euros, but that is still a hefty sum. How will the institutional investors behave over the coming 12 months, and what will happen if their borrowing conditions on the North-American money market funds become stiffer? Many other events could aggravate the international crisis. One thing is certain: the present policies of the EC, ECB and IMF cannot result in a favorable outcome.

CADTM: On several occasions you have written that the private debt was far greater than the public debt. So far you’ve been talking about public debt.

Eric Toussaint: There is not a shadow of a doubt that the private debts are much higher than the public debts. According to the last report by the McKinsey Global Institute, the sum total of private debt worldwide comes to U.S. $17,000 billion [$17 trillion — ed.], i.e. about three times the sum of all public debts. There is a great risk that private companies, including banks along with the other institutional investors, will not be able to repay their debts.

Bankers, chief executives of other companies, the traditional media and governments only discuss public debt and use its increase as a pretext to justify new attacks on the social and economic rights of the majority of the population. Austerity and the reduction of public deficits by axing social budgets and civil service jobs have become the only way of raising funds, along with privatizations and more consumer taxes. For appearances’ sake in Europe, some governments have added a tiny tax for the rich and talk of taxing financial transactions.

Obviously the increase of public debt is the direct result of 30 years of neoliberal policies. They have used loans to finance fiscal reforms in favor of the wealthy and of large private companies. They have rescued banks and large companies by getting the State budget to take on part of their debt or other losses. Due to the recession, there have been new falls in tax revenues and an increase in some public spending to help victims of the crisis.

The combined effect has been to increase the public debt. It all comes down to deliberately unjust social policies which aim systematically to favor one social class only. A few crumbs are tossed to the middle classes to keep them quiet. On the other hand, the great majority of the population have been hit by these policies and seen their rights trampled underfoot.

That is why the public debt has to be seen as globally illegitimate. And that is why I have been focusing on the public debt in this interview, because we absolutely must find a positive solution to this problem.

[The first five installments of this interview are respectively “Greece,” “The great Greek bond bazaar,” “The ECB, ever loyal to private interests,” “European Brady deal: austerity for life,” and “CDS and rating agencies: factor(ie)s of risk and destabilization.”]

November/December 2011, ATC 155