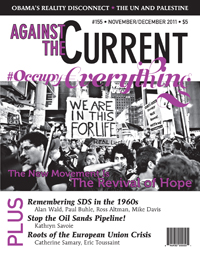

Against the Current, No. 155, November/December 2011

-

Three Years After "Yes We Can"

— The ATC Editors -

The Obama Reality Disconnect

— Malik Miah -

Stop the Keystone XL Pipeline!

— Kathryn Savoie -

Big Three Auto Contracts: Lowlights of 2011

— Dianne Feeley -

Dollarization, Democracy & Daily Life in Zimbabwe

— K.D. -

The UN & the Future of Palestine

— David Finkel -

The Boomerang Is Almost Home

— Jimmy Johnson -

Crisis in the EU: From the Periphery to the Center

— Catherine Samary -

Has Europe's Crisis Peaked Yet?

— an interview with Eric Toussaint - Bolivia's Growing Crisis

-

On Troy Davis

— Theresa El-Amin - Remembering SDS

-

A Theater for the Poor

— Alan Wald -

Memories of [my] Syndicalism

— Paul Buhle -

In Memory of Carl Oglesby

— Ross Altman -

Carl Oglesby: A Mentor & Leader

— Mike Davis - Reviews

-

Bolivia's Uncertain Revolution

— Dawn Paley -

A Revolution's Heritage

— Marc Becker -

A Family, A Tragedy, A Movement

— Karin Baker -

Class & Race in A Modern Catastrophe: Lessons of Katrina

— Derrick Morrison -

Looking North for Labor Revival?

— Barry Eidlin - Dialogue

-

Wrestling with Ellison

— Paul M. Heideman -

History, Theory, Politics & Invisible Man

— Nathaniel Mills

Ross Altman

Ravens in the Storm:

A Personal History of the 1960s Anti-War Movement

Carl Oglesby

Scribner, 2008, paperback reprint 2010, 352 pages, $22.

[Carl Oglesby died on September 13, 2011. We present this review as a memorial tribute. — The ATC Editors]

FORTY-SIX YEARS ago this November, then-SDS president Carl Oglesby stood on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. and told those assembled to protest the war in Vietnam that the men who were responsible for that war were not evil, they were “trapped in a system.” They were, like Antony had told the crowd of those who had killed Caesar, “all honorable men.” Indeed, they were all liberals.

He went on to describe that system as “corporate liberalism,” which somehow managed to do collectively what as individuals they would most likely condemn: “study the maps, pull the triggers, drop the bombs and tally the dead.” He told the liberals who had gathered to protest that war that perhaps there were two kinds of liberals — those who operated that system, and those who, like the SDS protesters who had joined the more moderate members of SANE (Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy — ed.), wanted to change it.

Then he suggested what changing it would require: building an antiwar movement “with a most relentless conviction.” “Help us shape the future,” he ended, “not in the name of this or that ism, but in the name of plain human hope.” With that speech, later reprinted in countless magazines and anthologies of classic documents of the 1960s, Oglesby became the leader of the antiwar movement.

Ravens in the Storm: A Personal History of the 1960s Anti-War Movement, looks back on those days with both passion and detachment, humor and a clear sense of the opportunity wasted, and succeeds in vividly recreating the struggle to end a war that Americans increasingly opposed but didn’t know how to end.

His personal memory is aided by the use of over 4,000 pages of documents he managed to retrieve through the Freedom of Information Act. During the years he led SDS and the antiwar movement he was under constant surveillance by both the FBI and CIA.

Yet Oglesby is at great pains to point out that he was not the dove they thought he was. Indeed the title of his book redefines the conflict between the cold warriors and the anti-warriors as not between hawks and doves, but rather hawks and ravens. Going all the way back to the story of Noah’s Ark, Oglesby recovers the first bird that Noah released from the Ark — not the dove who came back when the storm was over, but the raven who flew out into the teeth of it and never returned.

It is in that raven that Oglesby finds a symbol for what SDS faced when it confronted the president and vice-president, the secretary of defense and the secretaries of state and national security: The students who were the prime movers of the antiwar movement were the ravens in the storm.

As their leader it is not surprising that Carl was eventually labeled “the most dangerous man in the movement.” What is surprising, and makes this book a remarkable reconstruction of the second defining clash of the 1960s (along with the Civil Rights Movement), is that it was not the FBI or the CIA that called Oglesby the most dangerous man in the movement — but SDS itself.

Thereby hangs a tale, and that’s exactly what this tells — the story of how Oglesby went from being the president of SDS to an outcast, a pariah, abandoned by those he had trusted most, a stranger in a strange land. Because Carl is able to look at it all with a poet’s eye as well as a dramatist’s (which he also was), he is able to find in these emotions recollected in tranquility a genuine “fanfare for the common man.”

For five years he was in the eye of a hurricane, at the center of the storm, and through his eyes we who were there are able to relive it or, for a younger audience, to discover the source of the ’60s lasting hold on the American imagination.

The Road to Radicalism

Oglesby came to SDS accidentally — he was no student radical looking to join up. In short, he didn’t find them — they found him. At a time when student radicals were warned “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” Carl Oglesby was 30 years old and working for the defense industry’s Bendix Corporation in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for whom he had “Secret Security Clearance,” and worked as a tech editor.

Entrusted with military secrets, he was surely no natural in training for the position of president of SDS, whose members were now turning a critical eye to the war raging in Southeast Asia. But fortuitously, Carl had been asked to prepare a briefing on the war for his bosses, who, oddly enough, wanted to know the truth of what was happening and where their research was taking them.

Even more oddly, Carl was invited to publish his findings in the University of Michigan student paper, where some SDS members were sure to spot it. They did, and were surprised at its critical tone towards the administration. They asked Carl if they might circulate it amongst SDS people, and before he knew it, Carl was asked to write a different kind of statement on the war for an anti-draft action to take place in New York. One thing led to another, and Mr. Oglesby, with his coveted blue badge secret security clearance on his jacket, was soon to face Robert Frost’s road not taken. Like Frost, Oglesby took it, left the defense contractor, and was elected the new national president of SDS on the strength of his very first statement against the war, and his strong views that Vietnam should now become the focus of SDS’s campus organizing across the country.

Already the site of Tom Hayden’s Port Huron Statement — the founding charter of SDS — the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor was the ground floor in the burgeoning student movement, and SDS was the group that resonated most on campus. They were looking for a leader at precisely the time this brilliant bohemian with a steady job and a proven ability to speak truth to power came right to their doorstep.

Before Carl became the leader of SDS it was principally dedicated to community organizing in northern ghettoes, and saw itself as a northern, white version of SNCC, the southern (mostly) Black Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee. SDS saw a need to create a new kind of political organization up north that would empower local people to become advocates for themselves to improve their lives in the poorest neighborhoods — the people whom socialist Michael Harrington had dubbed “The Other America.”

SDS co-founder Tom Hayden organized in Newark, New Jersey one of many SDS model programs they called “ERAP,” for “Economic Research and Action Project.” In Los Angeles, author Mike Davis began his political career as a radical by becoming the Regional Director of the SDS house, located in one of the poorest neighborhoods surrounding USC. The ultimate goal of such organizing was to create a society based on “participatory democracy.”

When Carl became SDS president he steered it to become the national voice of the antiwar movement. With a prodigious output of essays and speeches on American foreign policy and the encrusted war machine it had spawned, Carl focused his efforts on bringing the war in Vietnam into a radical critique of America’s newly perceived role as the world’s policeman, as Phil Ochs summed it up nicely in his song “Cops of the World.”

Carl was a radical, all right, but also displayed a tendency — unsettling to some — of being willing to talk to people on both sides of the political spectrum, to create allies on what he called “the old right,” whom he saw as having a potential affinity for “the new left.” He even saw no conflict in responding favorably to requests from those in the business establishment who occasionally sought him out as a corporate speaker — this from the man who gave the name of “corporate liberalism” to the system that he held responsible for the crime of Vietnam.

In the later incarnation of SDS as the “Weather Underground,” leaders like Bernadine Dohrn had no interest in changing and reforming America — the stated goal of early SDS leaders like Tom Hayden, Al Haber, Paul Potter, Dick Flacks, and most eloquently, Carl Oglesby. To them, Carl’s ability to win over converts from all corners of society made him “the most dangerous man in the movement” indeed.

This nonviolent anti-warrior used words as his weapons, and in his ability to make them soar, found an image that resonates throughout Ravens in the Storm. It is chock-full of stories and personalities that come alive — both his friends and antagonists — and will make the reader appreciate why of all the groups that left their stamp on that decade of change, SDS alone has spoken to a new generation of student activists who are forming chapters of the “new SDS.”

I hope they find this book, and reap the benefit of a life of political wisdom sown in the streets of America. In closing, here is one story Carl left out of his magnificent recreation of the antiwar movement he helped to build.

Saying Goodbye

When it came time for Carl to give up his position as President of SDS we were holding the National Council in Clear Lake, Iowa, the city that said goodbye to Buddy Holly in 1959 — before his plane crashed on “the day the music died,” as songwriter Don McLean would later memorialize it.

I was a delegate there as president of SDS from UCLA, and Carl was already my political hero, ever since that masterful speech at the March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam on November 27, 1965, the year he took office as the national president. But he became even more of a hero to me when I saw what transpired at the election of new officers in Clear Lake.

Presidents of SDS served for a one-year term to prevent the entrenched concentration of power in a few hands, which was one of the things SDS had first organized to challenge in the United States. But Carl was so popular, and had presided over such an amazing expansion of SDS across the country because of his personal charisma as both a writer and a speaker, that no one wanted to let him go.

There was a clear consensus to suspend the rules of our organization and make him president for another term. In effect, he was being asked, like Caesar, to pick up the crown and put it on. And had he done so, he would have been reelected by acclamation. Carl refused. But it was the way he refused that has endeared him to me throughout the years.

When he saw the way the tide was moving and that he was about to be swept up in it, he suddenly jumped up on the dining room table (we were meeting in the cafeteria of a local college) and gave us all a history lesson. He told us a story about George Washington, and how eight years after our republic was founded and he had served two terms as the first president, he was offered the opportunity to be made “president for life” by the first U.S. Congress, which did not want to turn the country over to lesser hands.

Washington thanked them for the offer and then reminded them that they had just fought a revolution to escape from one monarchy. As much as he felt honored by their trust, he said if we are going to have a republic in the United States, we had better start right now and get onto the business of electing a new president. He was going home to Mt. Vernon.

After Carl told that story he didn’t have to connect the dots — everyone in the hall knew it was time to let him go, that our struggle for participatory democracy transcended any one leader, and that SDS would continue to thrive without him as president. That moment was to me the single most moving event I would witness as a member of SDS for five years — watching Carl Oglesby walk away from power, and leave SDS in the hands of a new generation of leaders.

To this day he remains my political hero, and because of Carl I fell in love with history. He made me see that history was not the past — it has enduring relevance.

November/December 2011, ATC 155