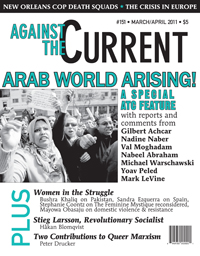

Against the Current, No. 151, March/April 2011

-

Change of the Century

— The Editors -

New Orleans' Police Death Squads

— an interview with Malcolm Suber -

Whither Social Security?

— Malik Miah -

Campaigning with Issues

— an interview with Ann Menasche -

Renewing New York

— an interview with Howie Hawkins -

Stieg Larsson in the Struggle

— Håkan Blomqvist - Arab World Uprising

-

Egypt and Beyond

— an interview with Gilbert Achcar -

The Meaning of the Revolution

— Nadine Naber -

Women, Revolution and the Future

— Val Moghadam -

From Tahrir to Palestine

— Nabeel Abraham -

A View from Israel

— Michael Warschawski -

Egypt Shakes the World

— Susan Weissman interviews Yoav Peled & Mark LeVine - Crisis in Europe

-

FRANCE: Battling Over Pensions

— Jason Stanley -

IRELAND: Slaying the Celtic Tiger

— John O'Connor -

GREECE: The Crisis Continues

— Nikos Tamvaklis -

UNITED KINGDOM: Students Fight the Fees

— interview with Ashok Kumar -

SPAIN: Women's Crises

— Sandra Ezquerra - Women in the Struggle

-

Pakistan's Dark Journey

— Bushra Khaliq -

Interrogating the Feminine Mystique

— an interview with Stephanie Coontz -

Claiming the Power to Resist

— Mayowa Obasaju - Triangle Fire Remembered

- Reviews

-

Arabs and the Holocaust

— David Finkel -

Toward A Queer Marxism?

— Peter Drucker

Susan Weissman interviews Yoav Peled & Mark LeVine

SUZI WEISSMAN INTERVIEWED Yoav Peled and Mark LeVine on her program “Beneath the Surface,” KPFK Pacifica Radio in Los Angeles, on February 11, 2010. The following are edited excerpts from those discussions. Thanks to Meleiza Figueroa for transcribing.

Suzi Weissman: I’m very pleased to have Yoav Peled join us right now to talk about the Israeli reaction to the events in Egypt, the relations between Egypt and Israel, and we’re going to ask Yoav about “Post-Post Zionism,” the title of Horit and Yoav Peled’s latest article in New Left Review, confronting the death of the two-state solution. Yoav is this year’s Hans Speer Professor at the New School for Social Research; he’s also a professor of political science at Tel Aviv University. His book Being Israeli: the Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship won many prizes, and his latest collection is Democratic Citizenship and War. Yoav joins us from New York. Welcome. So my first question to you is: what is the reaction in Israel?

Yoav Peled: The reaction in Israel is very, very nervous; naturally. Israel’s good relations with Egypt were precisely with the dictator. To the extent that Egypt democratizes — we still don’t know to what extent this will happen — Egypt will probably be less friendly to Israel. And I’m sure the U.S. government is also nervous, even though it has to say otherwise

To the extent that Egypt becomes more democratic, to the extent that there is a regime that is attuned to public opinion, it would be less friendly, or I should say less subservient to the United States and Israel. Of course we know that Saudi Arabia is very very nervous, and I’m sure Jordan too. So while a lot of people celebrate, there are a lot of people who don’t see a reason to celebrate in all of this.

SW: On the Egyptian side, can we assume that Gaza will no longer be an open-air prison and that the tunnels will no longer be blockaded?

YP: Well, I think this really probably the first point in which there will be a confrontation. I think that any regime in Egypt that is somewhat democratic will not be able to maintain the siege on Gaza, which Egypt has been maintaining in Israel’s service very religiously. They will probably open the border, but I think the reaction of Israel would be to re-occupy the border area from which it withdrew in 2005. This will be an immediate point of contention between Israel and the new Egypt.

Besides, the Muslim Brotherhood already announced that it is Israel that has not lived up to the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty of 1979, and they are right, because the first part of that treaty talks about the Palestinians. It doesn’t start with Israel-Egyptian bilateral relations, that’s only in the second paragraph. And Israel of course has not lived up to its obligations under the treaty with respect to the Palestinians.

SW: We’ve seen that there is a young generation, workers and others, who are ready to have democracy. And I guess the real question is, can you imagine this wind of fresh air reaching the Palestinian territories by a Jordan or Gaza?

YP: Well, Gaza and the West Bank are not in the same situation. Gaza is under siege by Israel, but internally governed by Hamas. Hamas, of course, is an offshoot of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, and they are celebrating what’s happening in Egypt. In the West Bank, if there is any attempt to imitate what happened in Egypt, it’s the Israeli military that will intervene, and it will not treat the Palestinians the same way the Egyptian military treated the Egyptians.

SW: But would they dare, in this atmosphere, to put it down brutally while the whole world is watching?

YP: Israel is not interested in the whole world. Israel is only interested in the United States, which is not going to interfere. I mean, we’ve already seen that the Obama administration is completely and totally in the little pocket of the Israeli government, to an extent that’s really amazing, even. So I don’t think Israel has to worry about anybody’s reaction, because the United States will support whatever it does.

SW: But I can imagine that with this democracy spreading, we can see the end of suicide bombers.

YP: There hasn’t been any suicide bombing since 2002. This is not at all the issue. This is not about suicide bombers, but Israel’s determination to maintain control over the Palestinian territories. It’s not a matter of the Palestinians changing; it’s a matter of Israel changing. And there is no indication that the lesson being learned in Israel, from what’s happening in Egypt, is that Israel should change its treatment of the Palestinians.

No More Two States?

SW: We’re also going to be talking about Yoav’s latest article with Horit Peled that appears in the latest New Left Review on the end of the two-state solution. Yoav, you’ve long been a proponent of the two-state solution, and yet in this article you posit the end of the two-state solution. You and Horit summarize the retreat to the right of Israeli intellectuals who were previously critical. Can you summarize what’s happened?

YP: The two-state solution is simply no longer an option. It was killed in July 2000 at Camp David, was killed by Ehud Barak [then Israeli Prime Minister, now Labor Party leader] with the very active help of Bill Clinton. Since then the development of Israeli settlements in the West Bank has been such that two states is no longer an option. It’s as one of the Palestinians used to say: while we’re negotiating about dividing the pizza, Israel is eating the pizza.

There’s simply no more land for the Palestinians to have a state. Many people thought this happened a lot earlier, I thought it only happened in 2000, but anyway we reached the point of no return in terms of Israeli settlements. The whole question of a partition of the territory is no longer there. I think we honestly have to face the fact that there is one state now, and that state is one where 40% of the population has no citizenship rights of any kind — and this is what needs to be changed. What we’re saying in our article is that we have to work now for a democratization of this state, where 40% have no rights.

SW: You also say, though, that the character of the state — as you talk about it — is a “post-Zionist state,” and that it would have to become a secular and democratic state. Is this something that you can actually see happening? And before you answer that, I wanted to ask, what is it that made the former liberals and so-called left in Israel move to the right?

YP: It was the combination of what happened at Camp David. The version told by Ehud Barak about what happened at Camp David, again the active assistance of Clinton, was that Israel offered Yasser Arafat everything, and that he refused. If Arafat refused to accept this generous offer, it means he doesn’t want peace. It means he wants the whole country, doesn’t want to have a partition of the country, and therefore we have no partner for peace.

That has been the slogan in Israel: “There is no partner for peace.” Since then the Second Intifada broke out, and then the suicide bombing happened on a very, very large scale. This was a real shock to the Israeli public in general, and Israeli liberals in particular. The psychological effect of the suicide bombings is simply unimaginable, and this is really what pushed almost the entire Israeli peace camp to the right.

SW: Do you think it’s also the fact that so many Russian immigrants came into Israel and supported the far right?

YP: Yes, that changed the balance of opinion. The Russians, however, were never liberals — of course, there are exceptions, we shouldn’t generalize completely — but by and large they never were. I’m talking about the Israelis who were liberals, the peace camp. It was, at its height, you could say almost 50% of the population.

Most of these people changed their views. Just in electoral terms, the two parties that supposedly represent the peace camp, Labor Party and Meretz, combined have 16 seats in the Knesset today. In 1992, they had 56 seats (out of 120). This shows you the change that’s occurred.

SW: But you also say — in looking at the books of these formerly liberal and so-called leftist intellectuals — that you detect the same colonial mentality there that exists in the rest of the, let’s say, pro-Zionist population. Has WikiLeaks, in revealing some of the attitudes of the Arab states as they pressured for an attack on Iran, for example, had any effect on Israel and on public opinion?

YP: Not really. There were more significant leaks, the Al Jazeera leaks of documents of the so-called negotiations between the Palestinian Authority and Israel since 2000, which showed that the Palestinians were willing to go to almost any length in order to reach an agreement, and everything they agreed to wasn’t enough for Israel.

These things always tend to reinforce people’s opinions. The Israeli mainstream said, “well, that shows that we don’t have a partner. Look, they didn’t agree to even more than that.” The few liberals left then said, “look, they agreed to so much, and we didn’t agree, so it means the Palestinians don’t have a partner for peace.”

SW: You’ve written so well in the past about the political economy of the peace process, and today as Mubarak gave way, I was thinking about the political economy of the Middle East as a whole. This obviously is going to change if the other dictators go. What do you think is going to happen if Israel is isolated, being the only one that supports the status quo.

YP: The most important thing is that Israel can no longer rely on Egypt. It doesn’t mean there will be a war tomorrow, or even that the peace treaty would be officially canceled. But from now on, in Israel’s strategic planning, including its defense budget planning, it will have to take into consideration the fact that in a future war, Egypt will not stand on their side as it has done since the signing of the peace treaty.

There’s also the question of commercial relations; 40% of Israel’s natural gas is provided by Egypt for relatively low prices as the result of a bilateral agreement, and there’s a whole series of other commercial agreements. This may also change. But Israel’s economy, as you know, is booming. Israel is not affected by the global crisis. It will be an additional economic burden, but it’s not anything that the Israeli economy couldn’t withstand.

As far as the chances for peace, the Israeli public has despaired of the chances for peace and is no longer even interested in that. There was a very interesting cover story inTime magazine a few months ago detailing that development, and I think they were right. Overall, it’s an added economic and military burden and a little bit more concern for Israel, but I don’t think in the short run anything fundamental will change.

SW: That’s sad. Let me ask you then, finally: you do say that the only real solution now is a secular democratic state, a one state, recognizing realities. Is that a wish, or is that something you think is eventually going to have to happen?

YP: I think it eventually will have to happen, or else the situation will be very unpleasant. I don’t think this is around the corner or anytime soon. But the fact that Egypt might now become democratic and if the same thing happens in Jordan, the pressure on Israel will increase, then gradually the realization will come that they have to solve the issue with the Palestinians. They can no longer keep three and a half million Palestinians as subjects with no rights, and by then it will be clear that the only way is to simply give them rights because there is no possibility of partition. So I think this could happen, but it’s really in the long term, not something that’s going to happen anytime soon.

Mark LeVine on Tahrir

Suzi Weissman: Well, there’s a fresh air blowing on the planet now; let’s hope it blows in all directions, and let there be a thousand Tahrirs. That’s my editorial statement. I’m very pleased to have with me — from Tahrir Square, and actually just right up above it — Mark LeVine. He is a professor of history at UC Irvine, and a senior visiting researcher at the Center for Middle East Studies at Lund University in Sweden. He’s also a musician and he’s bringing us music from Tahrir Square that was recorded yesterday. Mark speaks Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, Persian, Italian, French…and he’s an accomplished rock guitarist, and observer and writer. He’s blogging at aljazeera.net. Two important books of his are An Impossible Peace: Oslo and the Burdens of History (Zed Books, 2007) and Heavy Metal Islam: Rock, Resistance and the Struggle for the Soul of Islam (Three Rivers Press, 2008).

Mark, I’m so glad to have you on BTS. You’re now at the square in Cairo, it sounds like you’re next door. Tell us — we’re all just in jubilation today, as the news that not only did the Mubarak regime have to go with their tail tucked under, but that we’ve heard now that martial law has been lifted in Algeria.

Mark LeVine: Well, I think the most important thing about this revolution — and it was clear even from days ago, from when I first got here — that this is not just an Egyptian revolution, this is a world revolution, really the first revolution of the age of globalization. In many ways, 1989 was a revolution that closed the book on a previous era, and this in some ways takes us back to 1789, really at that level of importance.

When the news came, there was just such an incredible sense of jubilation. There were Italians and Greeks and Portuguese and Lebanese, and everyone was just saying “we won.” It wasn’t just Egyptians who won, even though certainly it is their revolution, but for them to nonviolently defeat this system, which so many countries have invested so much in maintaining — think about all the European leaders, and then Obama’s waffling, and then Israel, and then all the Arab countries who were all supporting Mubarak — is really the most important example to the world that I can think of in my lifetime.

I left Tahrir Square around seven this morning, after I don’t know how long… I had to take a shower and get some food. I went back to a nearby neighborhood, where my hotel is. When I left, I was nervous, and when I came back, I was very nervous because of the threats that [the appointed Vice-president] Suleiman, and certainly Mubarak and his police force, had made.

People here were ready for a bloodbath. And they were prepared, but the most interesting thing was when I came back and it was during the noonday prayer, there were imams on the street just urging the people to stay peaceful. That was the message: no matter what happens, don’t succumb to the violence and the provocations.

The fact that there wasn’t a provocation was an absolute miracle, because it would have been so easy for someone to come in here with a bomb, or to come in with a gun and just fire a couple of shots, and that would have led to a stampede that could have killed I don’t know how many people.

I guess it’s hard for people who weren’t here to understand how difficult it was to pull that off, because everyone really thought that today was going to be a day that was going to end in misery for hundreds of thousands of people.

Yet it never happened, and people just kept taking care of each other, and keeping it peaceful. And that is absolutely the reason for this victory, and it is a lesson for everyone. I mean, the first group that comes to mind is clearly Palestinians, because they’ve been shown a way to end the occupation in as quick a time as the Egyptians that ended their oppression, and the nonviolence is absolutely the key.

I just came in from being outside a couple of minutes ago, and the most striking thing is that the security cordon is gone. Anyone who’s been following the story probably has read about this intense security cordon, about five or six layers deep, of just volunteers from the square who frisk everyone over and over and check their ID to make sure those thugs of Mubarak can’t get back in, or anyone else for that matter who shouldn’t be there.

As late as this afternoon, that was still the case, and it took over an hour to get your way in. It was very dangerous while you were waiting there because if someone was walking by with a bomb it would have been a disaster. But now it’s gone, and everyone’s just moving completely freely, in and out, climbing on top of tanks, kids are on tanks playing with soldiers.

I think this is the hope. As so many friends of mine here said, “this is the true Islam emerging.” Everyone’s been waiting for it to emerge, but when you’re living under this kind of oppression, it’s so hard to have it emerge. Several people said, “This is the real jihad.” It was a jihad without violence, and it won, unlike the ones that use violence.

SW: Everyone here is asking, “Is this a leaderless revolution?”

ML: I don’t think the theory has been invented to really understand this yet. In a way, it’s spontaneous and so much of it wasn’t planned, because it was a response to events on the ground. But in the background there has been the labor movement; movements of young people who for years have been leading and having study groups and really trying to understand social theory and understand how to apply it in this situation; people who have been strategizing, who come like Wael Ghonim from the high-tech field who have been contributing in that way, but even as important are people who have been doing the hard work on the ground of grassroots mobilization.

It’s a combination of so many different things, and I don’t want to overemphasize its leaderless nature, but there’s certainly no one leader. Most of the people who are on TV, other than Wael who was the catalyst for rejuvenating this — all the older people from the previous generation who were trying to negotiate, really couldn’t represent this movement.

That’s probably why while they were in charge of the negotiation, nothing happened. It was only when the people on the street took control and refused to bow down that this move to a new phase was made inevitable.

SW: It seemed, because there are no more mass radicalized, nationalist parties and the Left has been so repressed there, that Islam was the only alternative. Yet that’s not what characterizes it either.

ML: No really, it wasn’t in fact. The Left still remains intellectually fairly strong. For a long time, people have said “oh, the Arab Left is discredited,” and certainly the older generation that came of age in the 1950s and ’60s has been utterly discredited. But the younger Left is a Left that we would all recognize from Seattle — the Left from Prague, a much more mature and sophisticated and progressive Left that is not weighed down by any particular ideology — they have been absolutely crucial.

This Left has been showing the way, even to the Muslim Brotherhood who everyone said was the organized force. Well, guess what happened at the end of the day — the Brotherhood was basically following a bunch of young longhaired Lefties. And that’s the God’s honest truth. Everyone has had to learn, and for years people are going to be trying to figure out how to emulate it. In the end it’s not going to be emulateable, because it’s local and came out of the roots here. Each country or each region is going to have to follow its own model.

There’s an incredible party right now but everyone knows tomorrow the war continues, and as many friends have said to me, “we’re not going anywhere.” They’re not cleaning out this square until they know in an absolute, ironclad way, that the military is guaranteeing the reforms that they had said today they would implement.

SW: Do these reforms include the end of the Emergency Laws, the freeing of political prisoners, the end of censorship?

ML: I mean, this is what people are demanding, and they are not going to leave — the majority of people who are organizing this hope they won’t leave in any major numbers until that is guaranteed.

No one thinks victory has been won in the long term. There is no doubt that the military is going to try to pretend to give what they can to get people off the streets, and then backtrack slowly — in a sense, that’s what’s already happened in Tunisia, where the repression is continuing and the system is in no way really dislodged.

I’ve talked to many Egyptians who understand that well, and they want to make sure that this system really is dead. That’s obviously a wise move. You know, when they were coming back from the Presidential Palace and they walked past one of the main Army buildings, and thousands of people stopped and started chanting to the Army building and the military leaders inside, “We are here, we are here, the Egyptians are here!” I saw it quickly on Al Jazerra — that was a statement.

Yes, they’re supporting the Army sort of, they recognize the army has played an important role, but they’re not going to let the army just take over and have a continuation of a military-led government. And it’s going to be a major ongoing negotiation, because the army has been one of the main beneficiaries of the last 20 years of liberalization.

That so-called privatization has really passed a lot of state industries into the hands of senior army people, and they’re going to have to give a lot of that up. No one gives up anything unless they have to. So that’s why, in many ways, this is a great beginning, but still the beginning of a much longer-term struggle.

SW: When labor got on the scene and started striking, it looked like that was really the end. That’s when Mubarak realized he couldn’t stay.

ML: I was in the square with one of the main organizers when he started getting the SMS text messages from his colleagues saying, “this is a strike, and these guys are striking, and those guys are striking.” He turned to me and said, “it’s all over.” And we all knew, once that happened, because Tunis was the paradigm for that. Once it moved from a localized strike in Cairo and several cities to countrywide labor strikes that was it — the system was finished.

SW: Given that you come from the United States even though you speak Arabic, have people talked to you about the Obama administration’s “dual policy” — on the one hand, he says the right thing, but Hilary Clinton’s State Department supported the “slow transition” and Suleiman — has there been any talk about that, or is that just in the background?

ML: You know, people are utterly disgusted with the Obama administration on the one hand, and on the other hand, they don’t care anymore. I’ve been writing very critical things about Obama in my columns, but in some way, in the end, it’s almost better they did it without him, because now it’s really theirs. As one friend said, “we did this by ourselves, no one came to help us and stood up for us.” And in that way, the victory is that much sweeter.

But when the dust settles, if there’s really a fully civilian led government of opposition figures, the United States and the Europeans are going to have a very hard time having much influence, and for them to maintain their privileges and their positions will certainly be much harder.

The main thing is going to be military aid, for example — the military wants to keep all its perks, and all the money, and all the aid that comes to it. Any civilian government, in order to have the kind of redistribution of wealth that will be necessary to have a fundamental change in the levels of poverty here, will have to take on the privileges of the military, and that’s really going to be the long-term struggle.

It’s a big party here tonight, but as everyone’s saying, “Tomorrow we start over.”

ATC 151, March-April 2011