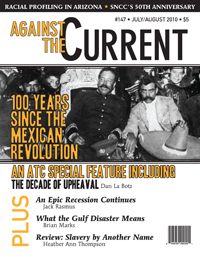

Against the Current, No. 147, July/August 2010

-

Bigger Slicks, Sicker Society

— The Editors -

Arizona's Racial Profiling Push

— Malik Miah -

Louisianans, Oil & Petro-Addiction

— Brian Marks -

The Unfolding Epic Recession

— Jack Rasmus -

The Limits of State Intervention

— Barry Finger -

After Obama's Health Care Law

— Milton Fisk - The U.S. Social Forum in Detroit

-

The Victory for Workers' Rights in Honduras

— Anthony Graham -

World Cup Woes for South Africa

— Ashwin Desai & Patrick Bond -

The 1960 Sit-ins in Context

— Marty Oppenheimer -

SNCC's 50-Year Legacy

— Theresa El-Amin - The Mexican Revolution at 100

-

¡Viva la Revolución!

— Dan La Botz -

Trotsky, Guest of the Revolution

— Olivia Gall -

Miners Protest Brutal Beatings

— Dan La Botz - Reviews

-

African Americans' Forced Labor

— Heather Ann Thompson -

Peace, Freedom and McCarthyism

— Mark Solomon -

Waging the War on Slavery

— Derrick Morrison -

Fighters with Disabilities

— Chloe Tribich - In Memoriam

-

Berta Langston, 1926-2010

— Alan Wald - Barbara Zeluck, 1923-2010

-

Recollections of Harry Press

— Carl Anderson, Arthur Brodzky & Dave Bers -

Lena Horne & Her Times

— Kim D. Hunter

Chloe Tribich

Call Me Ahab

A Short Story Collection

By Anne Finger

University of Nebraska Press, 2009, 206 pages,

$17.95 paperback.

AT LEAST SINCE the mid-20th century, writers in the United States have publicly debated the place of politics in fiction. Plenty of great authors, Flannery O’Connor among them, warned against saddling fiction with political intent. That some renowned writers have produced work that reveals human truths that belie their detestable politics — Jorge Luis Borges and Ezra Pound are two examples — might support O’Connor’s point.

Is good political literature possible? Is there a way to resolve the tension between fiction, which is about individuals, and politics, which is about groups? Certainly these questions should concern all of us who love books, but for consciously political readers and writers — particularly those who participate in real world organizing struggles — there’s even more at stake.

In her short story collection Call Me Ahab, Anne Finger plunges headfirst into this debate. In each of these nine stories Finger invents an interior life for an historical or fictional figure with a mental or physical disability. Some characters, like Vincent Van Gogh, are household names, while others, like Mari Barbola, the dwarf in a famous Velasquez painting, have been written out of mainstream history.

The literary ruse of centering the lives of the marginalized is of course common — just think of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead — but Finger adds an important twist. By focusing on disability, the author forces readers to reimagine the lives of disabled historical and literary figures both famous and forgotten and to question why some, like Helen Keller, are remembered solely for their disabilities while the disabilities of others, like Rosa Luxemburg, have been all but erased.

How did Rosa Luxemburg understand her limp, and might she have felt a kinship with Antonio Gramsci, whose spine was deformed? What if she had met him on the F train the day after the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed? How might Mari Barbola, the dwarf depicted in Velasquez’s famous painting “Las Meninas,” have manipulated her masters’ stereotypes to accrue more power for herself?

These are the sorts of questions that Call Me Ahab seeks to answer. From the first, Finger’s purpose is never in question: “Let’s get one thing straight right away. This isn’t going to be one of those movies where they put their words into our mouths,” asserts the young narrator of “Helen and Frida” as she imagines herself directing a Hollywood encounter between Helen Keller and Frida Kahlo. (4)

Here one understands that Finger is talking about her own book rather than giving voice to her character — just replace “movies” with “short story collections.” But this is supposed to be the voice of a child, and it’s a stretch to believe that a nine-year-old could command a penetrating filmic analysis along with a wealth of historical knowledge about the lives of Kahlo and Keller. And though this particular nine-year-old is obviously quite bright, it’s unclear how she is able to cultivate a sophisticated politics not shared by the world around her.

This is one of several examples of places where the author’s heavy-handedness interferes with otherwise very lovely and inventive writing. When given free reign, Finger’s characters point more effectively towards her politics than her own authorial statements. As in other stories of this collection, the better passages in “Helen and Frida” are those in which Finger allows herself to fully occupy the character’s head.

In the end the protagonist’s film-making fantasy becomes too intense, shocking her back to reality. What began as a somewhat humorous encounter between Kahlo and Keller turns into a sexual interlude tinged with desperation and hopelessness. Here is the protagonist’s closing rumination, which reminds us powerfully of how it feels to have “their words [put] into our mouths:

“My leg is in a thick plaster cast, inside of which scars are growing like mushrooms, thick and white in the dark damp. I think that I must be a lesbian, a word I have read once in a book, because I know I am not like the women on television, with their high heels and shapely calves and their firm asses swaying inside of satin dresses…” (13)

Dark Humor

There’s an appreciable amount of dark humor in this collection, too. One highlight is the depiction in “Vincent” of social security bureaucrats, whom Finger likens to the pit ponies of Borinage, Belgium, a mining town where the real Van Gogh was stationed as a theology student, and where the pit ponies lived and worked in the underground mines in conditions not much worse than those of the human mineworkers.

“Pale as white worms, [the social security workers] labor fourteen hours a day, wearing old fashioned green eyeshades and creosote cuffs. They sleep next to their desks on folding cots…they mate quickly, furtively in cubicles and broom closets, give shameful birth in the stalls of the women’s room. The new forms (SSA-L8170-U3; SSA-561-U2) appear mysteriously in the supply room; they take comfort in the notations in the upper-right-hand corners…These are directives from their God, OMB, whose face they cannot imagine, whose name they are forbidden to speak. ” (26)

The real Van Gogh was so moved by the lives of the Borinage mineworkers that he gave away his possessions and remained there even after he was expelled from the church. Finger’s figurative “pit ponies,” on the other hand, are cogs in a relentlessly dehumanizing machine. Vincent, too, seems more a symbol than a character — impoverished and ill beyond redemption, he is wasted by society until he takes he own life.

Finger is skilled at portraying masses of people — the tangles of bodies, their movements, their quick and often regrettable decisions. This comes in handy in a collection that includes bloodthirsty Philistine mobs and the scheming attendees of the congress of the Second International. In “Our Ned,” a group of laid-off milliners prepares to storm their former workplace:

“A few men had pots of ale, and who wouldn’t like a gulp of courage at a moment such as this? … And then the crowd made a noise which could perhaps be described as a holler or a yowl…Perhaps it is the bellow of the Luddites’ stomachs, cramped with starvation, would have given off had the individual organs within them the power of direct speech. ” (160)

Unlike most of the other stories, which feature characters who are either fictional or historical, the origin of the protagonist of “Our Ned” — a mildly retarded millworker who leads his coworkers in protest against mechanization — is couched in mystery. In a postscript, Finger cites a source for a story about a “youth of weak intellect who smashed the looms in a Leicestershire village” (160).

Call Me Ahab is an unusual collection, in part because it features disability as a theme and in part because of its historical and geographical variety. Finger has an admirable willingness to imagine worlds far beyond the contemporary United States, a trait that is unusual among contemporary American fiction writers.

At times Finger’s characters fall flat. At worst they are plainly boring, and her occasional references to markers of consumer culture — Vincent’s brother Theo sees a therapist who helps him “work through the thicket of guilt and envy” — come off as failed witticisms that suggest she lacks faith in her characters’ ability to carry the stories. These are the pieces better suited for political tracts than fiction.

Regarding the place of politics in fiction, novelist Claire Messud has written that the work of the writer is itself political: “A writer’s first job is “to convey, as best as possible and as comprehensively as one can, a world, known or imagined. To conjure the world as it might have been, to reflect the world as it is, to imagine the world as it could be — all are, or should be, radical deeds.”

ATC 147, July-August 2010