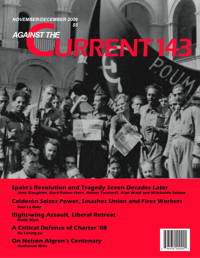

Against the Current, No. 143, November/December 2009

-

Reform Is Not A Tea Party

— The Editors -

Right-Wing Assault, Liberal Retreat

— Malik Miah -

Mexico's PATCO Moment?

— Dan La Botz -

South African Workers Tackle Neoliberalism

— Patrick Bond & Azwell Banda -

A Critical Defense of Charter '08

— Au Loong-yu -

On Darwin's 200th Anniversary

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

On Nelson Algren's Centenary

— Nathaniel Mills - Spain's Revolution and Tragedy

-

Introduction to Spain's Revolution & Tragedy

— David Finkel, for the ATC Editors -

Remembering Spain's Revolution

— Jane Slaughter -

A Classic Study Revisited

— Gerd-Rainer Horn -

Chronicles from the Front

— Reiner Tosstorff -

The Journey of James Neugass

— Alan Wald -

Introduction to The POUM's Seven Decades

— The ATC Editors -

The POUM's Seven Decades

— Wilebaldo Solano - Reviews

-

Fighting Lynch Laws in America

— Gerald Meyer -

Chronicling Labor's Crisis

— Dan Clawson -

Tearing Down the Gates?

— Debby Pope -

The Politics of Surrealism

— Amanda Armstrong -

Looking at Che Guevara

— Kit Adam Wainer -

Theories of Stalinism

— Paul Le Blanc - In Memoriam

-

Leon Despres, Chicago Rebel

— Frank Fried -

Indy's Lucas Oil Stadium Revisited

— George Fish - Letters to Against the Current

-

A Letter on Cuba

— Barry Sheppard -

A Brief Rejoinder

— Frank Thompson

Reiner Tosstorff

Letters from Barcelona

An American Woman in Revolution and Civil War

By Lois Orr with some materials by Charles Orr

Edited by Gerd-Rainer Horn

Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009. 209 pages,

$75 hardcover.

THIS VOLUME CONSISTS of carefully edited contemporary texts from the two U.S. socialists Lois and Charles Orr, who joined the revolutionary events in Spain after the outbreak of the Civil War, from fall 1936 to spring 1937. Two newlywed activists from the left wing of the U.S. Socialist Party, they had been traveling through Europe on their honeymoon when the news of the military revolt under General Franco reached them. They rushed to Barcelona not only to take a look but to become an active part of the workers’ revolution, which had erupted as the answer to the pro-Fascist coup.(1)

The capital of Catalonia in the North-East of Spain lies at the center of the industrially most developed part of Spain, then home to the perhaps most radical labor movement in Europe.(2) Together with the landless agricultural day laborers of the South, Barcelona’s workers formed the core of Spanish anarchism that had found its organizational expression in a radical union federation. The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo — National Labor Federation (CNT) — more than a million members strong, had to contest for hegemony over the workers’ movement in the other parts of Spain with the Socialist Party, but in Catalonia it was dominant.

The Communist Party had been rather marginal up to this time due to its sectarianism and history of bureaucratic splits and expulsions. It only began to grow after the outbreak of the Civil War, mainly because of the support the Republic received from the Soviet Union and because the political price Stalin demanded was not yet openly recognizable.(3)

In Catalonia there existed a small revolutionary Marxist current, which had emerged from the CNT under the influence of the October revolution. It criticized the political limitations of anarchism and stood for self-rule of the working classes based on the model of “soviets,” i.e. democratically elected workers councils. As revolutionaries they had clashed with Stalin’s rising dictatorship over international communism.

Partially influenced by the critique of Trotsky and after overcoming internal fragmentation, this current crystallized in 1935 in the POUM (Spanish or Catalan for “Workers Party of Marxist Unification”). Its strongholds were the small towns and the countryside outside Barcelona. Within the city itself it was second to the CNT, while in the rest of Spain its forces were rather weak. It was still far from being a full-grown party when the revolution broke out.

This meant that the POUM remained a force more driven by events than able to become a mover of them. Though often called Trotskyist, and despite broad sympathies with Trotsky’s struggle against Stalin and the provenance of a part of its militants from organized Trotskyism, it developed a series of political differences. This was particularly true when the POUM joined the Catalan government (September to December 1936). These differences in the short time of the revolution could not really be argued out, but obviously led to public confrontations.(4)

The Orrs, already influenced by the growing revolutionary tendencies within the Socialist Party — which were about to be reinforced during the summer of 1936 by the affiliation of the U.S. Trotskyists after the latter had dissolved their independent organization. The Orrs approached the milieu of and around the POUM, with Charles Orr joining the party and becoming editor of the POUM’s English language journal, The Spanish Revolution.

This organ provided a vivid picture of what was happening in Spain to the world, explaining the meaning of the revolution, its social content and the POUM’s struggle. It described how workers had reorganized factories and farms under their ownership and administration, and outlined how workers’ militias laid the first steps towards a revolutionary army.(5)

Being somewhat more critical of its heterogeneity, Lois Orr never formally joined the POUM. But when the POUM joined the Catalonia’s autonomous goverment she began to work in its foreign propaganda department. Not speaking Spanish or Catalan, nor being able to learn them during their short stay, she principally frequented the milieu of revolutionary foreign visitors who had been attracted to Barcelona.

Some took an active part in the revolution, but more than a few pursued the specific interests of their organizations by trying to win over the POUM to their “correct line,” making use of internal differentiations, often in a sectarian way.

A Woman in the Revolution

The bulk of the material in this book consists of excerpts from letters that Lois Orr sent back home to her family, communicating her day-to-day observations. Charles Orr occasionally contributed and some later material complements their impressions.

There already exist quite a few testimonies that describe these revolutionary events, some were even directly written to be published. If one only thinks of those by English-speaking militants, obviously George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia comes first to mind. There he narrates his experience of the military struggle on the Aragon front and the bitter clashes between different political factions. Less well known is Mary Low’s and Juan Brea’s Red Spanish Notebook, depicting the struggle on other fronts and highlighting the revolution in the hinterland.

So what does the Orrs’ testimony add? The editor, Gerd-Rainer Horn, a historian of modern European social movements at the University of Warwick, explains two central aspects in introductory chapters. One is the way a woman looked at these exciting revolutionary but very male-dominated events. Horn discusses her private correspondence within the context of recent feminist theories of women’s autobiographies.

The other chapter, originally published in the History Workshop Journal some years ago, examines the Orrs’ perception of the revolution through a “language of symbols.” As the Orrs did not know Spanish or Catalan, they had to come to an understanding of events through their symbolic expressions — such as the way people dressed and behaved, how political rallies proceeded etc. From this they drew their conclusions about the course of events and its political meaning.

These letters also contain detailed information about the “radical foreign” milieu in which they moved. With one exception the names mentioned only ring a bell with the few historians of the international radical left of the 1930s. The exception was Charles Orr’s British secretary, the wife of George Orwell. Of course, Orwell was fighting during these months at the front in Aragon.

At the time of their arrival the revolution was still in its heyday. But this soon changed, as they could closely observe. The external pressure of the Fascist advance, due to the unlimited help received from Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, reinforced the internal contradictions between revolutionaries and the social-democratic and left-liberal reformists who wanted to reverse the revolutionary conquests workers made when they had crushed the military revolt in the main cities.

The latter forces received essential support from the Soviet Union. Stalin, whose main international strategy at that time consisted in forming an alliance with liberal-capitalist Britain and France against Germany, had renounced any anti-capitalist goals as these would have been incompatible with such a foreign policy.

During the first two crucial months of the Civil War, the Soviet Union had therefore refused the help the Spanish republic desperately requested. Only when realizing that a rapid victory of the Fascists would decisively turn the balance in favor of Nazi Germany, and that further refusal to help would definitely damage his reputation, did Stalin decide to send military support. In the expectation this would benefit the Soviet Union’s projected international alliance he also made it clear that he wanted to suppress “revolutionary exaggerations.”

The Communist Party, equipped with new prestige, now began a direct assault on the revolutionary conquests. As the anarchists were too strong to be directly confronted, the main aim was now the POUM, which was calumniated as “Trotskyite wreckers” and “agents of Hitler.” This was the time of the massive “purges” in the Soviet Union and these were to be extended to the international workers movement.

In May 1937 an armed confrontation, provoked by the Communists and immortalized by Orwell, led to street battles in Barcelona, and the workers’ defeat.

In the first place, the anarchists had not been willing to “fight for power.” The POUM accepted this limitation. Trotsky had already critized the rather cautious and reluctant tactics of the POUM. With this defeat there were even fiercer polemics, and these are reflected in the Orrs’ letters.(6)

The events of the May days were used by the Stalinists to suppress and scapegoat the POUM. Many activists were arrested and the party made illegal. The aim was to organize a show trial with defendants who would “confess” having acted in the pay of Hitler — forced, of course, to confess by means of torture.

The most famous case was that of the POUM’s main leader Andreu Nin, an internationally known working-class figure who “disappeared.” (He refused to cave in and was subsequently assassinated by Stalinist agents. This was immediately suspected, but only with the end of the Soviet Union was it substantiated through the Soviet archives.)

Foreigners were another target as this was to prove an “international conspiracy.” The Orrs were among those arrested; they describe the horrors of their experience in the book’s final section. They were lucky, however, as their arrest caused an outcry in the United States and they were released.

The fate of the German and Italian revolutionaries, obviously without any diplomatic support from their fascist governments, was much worse.

The Orrs returned to the United States after a stay in Paris where they met other refugees from the repression in Spain. They joined the U.S. Trotskyists, now again in an independent organization and, when it split in 1940, were active in the Workers Party (the “Shachtmanites”).

Memory Recovered

All these texts are thoroughly edited with footnotes explaining biographies and events. An introduction gives a short summary of the revolution in Catalonia. A fortunate addition are illustrations Horn found in contemporary drawings by the Catalan artist Josep Bartolí, who at that time was close to the POUM. In a dense and detailed way his drawings depict scenes from the revolutionary struggle and convey its political atmosphere.

Letters from Barcelona is a welcome antidote against the loss of memory of one of the most important revolutionary events in the history of the international working-class movement. For a long time the story has only been remembered by a narrow milieu of the independent left, perhaps because it ended in such a terrible defeat.

To be sure, this has already begun to be overcome in the last years by other contributions as well. In a large part this is a long-term result of the marvelous movie Ken Loach made in 1995 about the fate of an international volunteer in the militia of the POUM, “Land and Freedom.” Now Hollywood has announced a film version of Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia (reported by Variety in May 2009) which will certainly have a bigger budget than Loach had, and will almost certainly reach many more screens, but will be probably less political.

Recent publications deal with what undisputedly constituted a “path not taken” but which in times of a growing capitalist crisis, and after the collapse of Stalinism, arouses interest as a potential historical alternative. Obviously the attention is most developed in Spain.

Over the past few years activists interested in the fate of the POUM and the history of the struggles in which it took an active part — and with the help of its few surviving militants — have republished many of its old texts accompanied by new historical research. An important element of their work is their constantly expanding website in Spanish and Catalan (www.fundanin.org/ http://fundacioandreunin.com).

Notes

- The historiography of the Spanish Civil War is immense. A good introduction to it is Andy Durgan, The Spanish Civil War, Basingstoke 2007. For an overview based on a selection of principal primary sources see George Esenwein, The Spanish Civil War. A modern tragedy, New York 2009.

back to text - However, the nationalities’ question should not be overlooked as an additional instigator of the political and social struggles. Catalonia has a language and a culture, distinct from “Spain,” i.e. from Castilia, the region around the capital Madrid. Conflicts between the center and the Catalan periphery have shaped the political landscape of Spain since the 19th century.

back to text - For the historical background of the peculiar development of the Spanish labor movement see Benjamin Martin, The Agony of Modernization. Labor and Industrialization in Spain, Ithaca 1990.

back to text - Certainly, the POUM is dealt with in the general historiography of the Civil War, albeit usually rather briefly. To date there is only one English-language history of the POUM: Victor Alba and Stephen Schwartz’s Spanish Marxism versus Soviet Communism: A History of the P.O.U.M., New Brunswick 1988. Its main author, Victor Alba had been one of its younger militants during the Civil War years. He had written the book before Franco’s death, and without access to a larger collection of contemporary sources, which were unavailable or difficult to find, had been forced to rely on his memory. Although he tried to be as accurate and objective as possible, one can note that Alba’s political origins did not lay in the Trotskyist part of the POUM. For Trotsky’s attitude see Leon Trotsky, The Spanish Revolution 1931-1939. Introduction by Les Evans. Ed. by Naomi Allen and George Breitman, New York 1973. For a critical discussion of Trotsky’s positions and the response of the POUM see Andy Durgan, “Marxism, War and Revolution: Trotsky and the POUM”, in Revolutionary History, No. 2, Vol. 9, 2006, 27–65.

back to text - This journal was reprinted in the 1960s and can be found in major libraries. Reading it still brings alive the atmosphere of Spain in those months.

back to text - An informative selection of contemporary statements and articles from the international revolutionary left on Spain and especially the POUM together with new analyses has been published in two issues of the British journal Revolutionary History: Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 1988, “The hidden history of the Spanish Civil War,” and Vol. 4, Nos. 1 & 2, Winter 1991-92, “The Spanish Civil War. The View from the Left” (the latter has now been republished as a book: Monmouth 2007).

back to text

ATC 143, November-December 2009