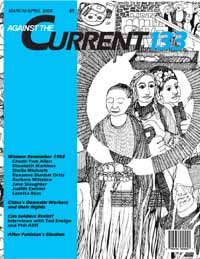

Against the Current, No. 133, March/April 2008

-

Looking Back -- and Ahead

— Letter from The Editors -

Voter ID Laws, Voter Fraud

— Malik Miah -

Can Soldiers Resist?

— interviews with Tod Ensign and Phil Aliff -

The Obama-Clinton Contest

— Dianne Feeley -

After Pakistan's Election

— Farooq Tariq -

Kenya's Opposition Party

— Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ - Congo's War, Women's Holocaust

-

On Hunger and Capitalism

— Dan Jakopovich -

A Rejoinder to Joel Kovel

— David Finkel - Women Remember 1968

-

Confronting the -isms

— Chude Pam Allen -

Forty Years of Defying the Odds

— Sheila Michaels -

My Year of Transition

— Elizabeth "Betita" Martinez -

Becoming a Revolutionary: Interview with Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

— Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz -

The Year of Awakening

— Barbara Winslow -

A Time for Learning

— Jane Slaughter -

My 1968 in the Heartland

— Judith Ezekiel -

"Intersectionality" in Real Life

— interview with Loretta Ross - Honoring International Women's Day

-

Domestic Work and Rights in China

— May Wong -

Women Stand Up, Fight Back

— Chloe Tribich -

Hitting the Maternal Wall

— Sonya Huber-Humes - Reviews

-

A War Plan Scuttled?

— Allen Ruff -

Funding Revolutions?

— Aileen Anderson -

Kicking Ass for the Working Class

— Kim Moody -

A Working-Class Hero Is Something To Be

— Steve Early -

Globalization in the Academy

— John O'Connor - Letters to Against the Current

-

Response to George Fish

— Malik Miah -

Racism and Responsibility

— George Fish

Chude Pam Allen

I LOVE THE name Against the Current and would add that to be active in the Women’s Liberation Movement at the beginning of 1968 was to be “against the current.” And “the current” then was as much the Left and the Black Nationalist Movement as it was the society as a whole. We were mostly white women, mostly middle class in background. Who we were was used against us opportunistically by the Left and the Black Movement to keep from having to address the issues of sexism — a word we didn’t even have back then.

Those early attacks on women’s liberation as being white, and therefore racist, contributed to a polarization, an either/or paradigm. You could be for Black liberation or Women’s Liberation, but you couldn’t be for both. That’s what our critics said. It’s not what we said.

I am one of the earliest organizers of the Women’s Liberation Movement. I am also one of the white women who had been active in the Southern Freedom Movement before we started women’s liberation. I wanted to build a movement that would stand against both racism and sexism and I wanted white women to be able to join with women of color whenever we could. I wasn’t alone in wanting that.

But the attacks made our ability to understand and confront racism within the Women’s Liberation Movement that much more difficult. We needed help to understand how to identify and then struggle with the white supremacy and class bias that was bound to manifest in those groups made up primarily of more privileged, college-educated white women. We needed help, not attacks. Not put-downs.

The charges of racism were effective in keeping some anti-racist white women as well as women of color away. The attacks also dismissed the women of color, who were raising issues of sexism. They rendered invisible, by pretending they didn’t exist, the women of color who came to women’s liberation meetings and events. But we were never all white, just as we were never all middle class.

I was lucky. Pat Robinson, a middle-class, educated Black woman who was part of a group of mostly poor Black women in Mt. Vernon and New Rochelle, came to visit me in December 1967. She wanted to know about our women’s liberation group in New York City. After listening respectfully to what I had to say, she told me about their group. She advised me to think in terms of class. Pat Robinson gave me a base to stand on, one that put the needs of poor Black women ahead of the rhetoric of the Black Nationalist Movement.

The Importance of Respect

Much of my work in the early years of the Women’s Liberation Movement was towards educating myself and other white women (and some women of color) about white supremacy and racism, including how it manifested in the women’s suffrage movement.

My experience was that when white women were offered the opportunity to learn about racism and white supremacy in a respectful setting that treated them as decent human beings, they were eager to learn and wanted to change. Of course, one workshop or lecture will not root out racism in any of us. But my own experience is that respect makes a difference.

In the 1990s I had an experience which showed me that the charge of racism is still used to discount (rather than analyze) the Women’s Liberation Movement. I’d visited the office of an official at the university where I work in research administration. With the exception of the receptionist, a young white woman, the office was empty. She was new and I asked her a few things about herself.

She’d just graduated from college, she said, as a women’s study major. “I was in the early women’s liberation movement,” I responded. “Oh, that was racist,” she answered, dismissing me — and the Women’s Liberation Movement — with a wave of her hand. I felt as if I’d been slapped in the face.

In a subsequent conversation I learned that the receptionist had a woman of color as her professor for her women’s history class. She was angry about how she and the other white women had been treated. The receptionist was also angry with the organizers of the Women’s Liberation Movement for having failed to eradicate racism. What was clear to me was that she had been emotionally battered.

When Pat Robinson visited me that afternoon in December 1967, she met a passionate young white woman who cared deeply about ending racism and sexism but didn’t have a clue about class struggle or the insidious ways bourgeois culture would replicate itself.

Pat knew, I’m sure, that I would get caught time and again by my narrow perspective and idealism. Yet she didn’t slam me against the wall for my inadequacies. She encouraged me to think about class struggle and to develop an international perspective. She encouraged me to go right on organizing women’s liberation. She treated me with respect.

What lessons would I like to pass on to activists today? Obviously I think we should treat each other with respect. Everyone deserves that. And I would add something I learned in Cuba in 1972 when I was privileged to build houses as a member of the Venceremos Brigade.

The Cubans had a concept of uneven development. That is, human beings developed unevenly and all of us had vestiges of bourgeois ideology and practice to work on. That puts 1968 into perspective: The white women who organized Women’s Liberation groups, and the activists in the Left and the Black Nationalist Movement, were all unevenly developed, as were women of color organizing independently.

We all had blind spots. We all had internalized the elitism and hierarchical social relations of capitalism. And we all had clarity on some issues. Some had a deeper understanding of capitalism and racism. But nobody in 1968 had a deeper understanding of sexism than the women — white and of color — who took their stand “against the current” of patriarchy.

We were straightening nails one day in Cuba. It was a job that most of the Brigadistas hated because it was tedious and in the end, all you had to show for it was a pile of nails. But it was the one time we could talk. This day a Cuban said to me, “To be a revolutionary is to make mistakes.” I have found that incredibly helpful over the years.

ATC 133, March-April 2008