Against the Current, No. 118, September/October 2005

-

On to September 24th!

— The Editors -

The NAACP's Future

— Malik Miah -

Muslims in Britain: After the London Bombs

— Liam Mac Uaid -

Solidarity with Iraqi Labor

— Traven Leyshon and Dianne Feeley -

The Message and Meaning of Groundings 2005: Walter Rodney Lives!

— Sara Abraham -

Creating A Movement for Reparations

— Andrea Ritchie -

Economic Crisis & Fundamentalism

— Susan Weissman interviews John Daly -

Kyrgyzstan After Akayev

— Susan Weissman - Attacks on the Academic Left

-

Assaulting pro-Palestinian Activism: Smear Tactics at U-M

— Nadine Naber -

Labor Studies Under Siege

— Stephanie Luce -

Racism & Conflict at Southern Illinois

— Robbie Lieberman - Celebrating the Revolutionary Centenary

-

Rehearsing for 1917: Russia's 1905 Revolution

— David Finkel -

A Hidden Story of the 1905 Russian Revolution: The Unemployed Soviet

— Nikolai Preobrazhenksii -

Rosa Luxemburg & the Mass Strike

— Lea Haro -

Lessons from the 1905 Revolution

— Hillel Ticktin - In Memoriam

-

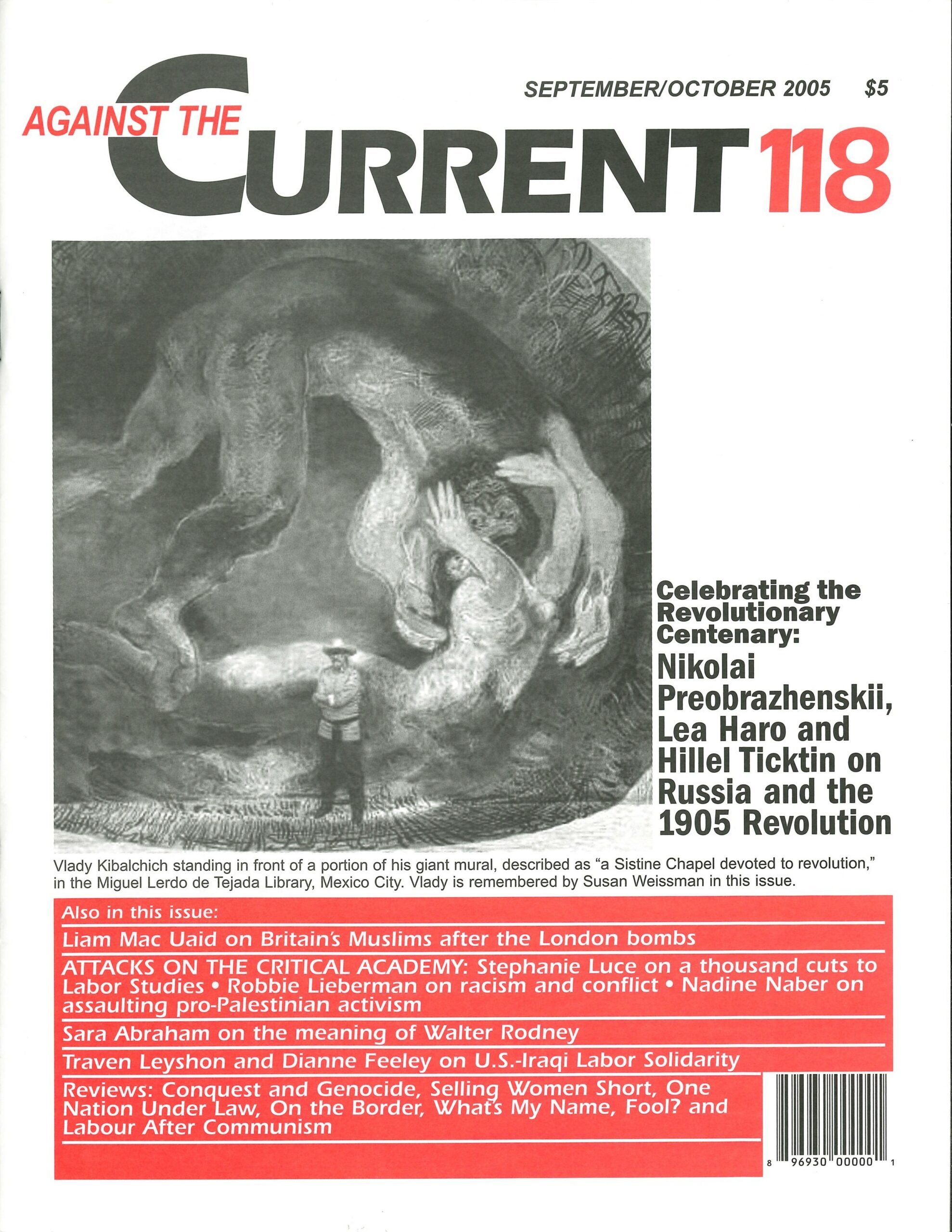

Remembering a Revolutionary Artiist: Vlady Presente!

— Suzi Weissman - Reviews

-

U.S. Law: Religious or Secular?

— Jennifer Jopp -

From the Front Lines of Native Women's Struggles

— Andrea Ritchie -

Fighting the Wal-Mart Plague

— Karen Miller -

Sports & Resistance

— Peter Ian Asen -

An Israeli Anti-Zionist Memoir: On the Border

— Larry Hochman -

Already in Hell: Labor After Communism

— George Windau

Stephanie Luce

MORE THAN A decade since the collapse of the Soviet Union, leftists are now more likely to be targeted by the right wing as “terrorists” than as “communists”—yet redbaiting is alive and well in the field of Labor Studies. In recent years, university labor programs have been attacked in the press for their teaching and research, and been targeted by university administrators for drastic budget reductions or elimination.

For example, I work at the Labor Center at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. In 2002, the University system faced severe budget cuts when the state went into recession. But the Labor Center was the only academic department that the Chancellor proposed to cut, commenting that if the program was so important to the labor movement, the unions should fund it altogether.

After waging a campaign, the Center managed to survive -—just barely. It has been told it can remain only by dramatically increasing its workload with fewer resources and staff. The Center must increase the number of classes it offers, the number of students it teaches and amount of grants it brings in, with 25% fewer faculty and 75% fewer staff. Class sizes are up and student funding is down.

The situation at UMass can be seen elsewhere. The Labor Center at Florida International University underwent significant cuts in recent years, and the Industrial Relations program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was eliminated entirely.

This May, six employees at the Indiana University Division of Labor Studies were laid off, including three faculty members. According to Professor Ruth Needleman, the department was told that university budget cuts necessitated the layoffs and the closing of the South Bend office.

Downsizing and Privatizing

The attacks on Labor Centers are partly a result of a larger trend to privatize public universities. Abandoning the land-grant mission of many universities, administrators are looking to cut back any departments that can’t serve as a “profit center” by bringing in lucrative research grants.

At the same time, universities are looking to cut tenure-track faculty and fulltime staff, replacing them with non-union, low-wage adjunct professors and part-time and seasonal staff. This was exactly the case at Indiana University. As Professor Ruth Needleman writes, “not only were tenure-track faculty terminated, but part-time, temporary and less credentialed employees were kept. The decision on whom the ax would fall did not follow IU policy; it ignored seniority, credentials and faculty governance. Welcome to Wal-Mart University!”

Beyond the general attacks on public university budgets, many faculty believe there are political motivations specifically aimed at labor studies programs. Although labor studies has never been a popular field with university administrators, and has always been grossly ignored in terms of resources, the last few years have brought an increase in attacks on the discipline.

In 2003, the Wall Street Journal published an article called “Picketing 101,” meant to “expose” the diverting of public dollars going toward union training programs “aimed at organizing efforts instead of educating students.” According to David Bacon, the article’s author Steve Malanga was supported by right-wing foundations to write about how labor studies programs were revising their curriculum alongside the AFL-CIO’s attempts at renewal.

In another widely-circulated article from the New York Sun titled “‘Living Wage’ is Socialism,” Malanga attacked the living wage research conducted by labor center faculty at a number of campuses.

What the Fight’s About

It is true that some labor studies programs grew in size and scope during the Sweeney era. They still offered courses on arbitration and costing contracts, but added more on organizing models, globalization and labor-community coalitions.

According to a study on the state of labor education programs released in 2004, Barbara Byrd and Bruce Nissen found that labor education programs are more extensive today than they were 40 years ago, and that the content of the programs has shifted in recent years “from what could be called “union maintenance” topics (negotiations, contract administration, etc.) to “union building” or “union growth” topics (rank-and-file involvement and mobilization, organizing, contract campaigns, etc.).”

In addition, labor studies faculty have provided research that unions and their allies have relied on to pass pro-worker legislation. Labor studies students have interned with unions and groups like United Students Against Sweatshops and Jobs with Justice.

These labor studies programs are no more “partisan” than your average business school, and are far outnumbered and out-resourced. Yet their growing prominence was enough to worry anti-union administrators and legislators.

In 2004, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger tried to eliminate the Institute for Labor and Employment (ILE) at the University of California. It wasn’t just general budget problems that provoked the Governor’s attacks: the ILE was singled out specifically. ILE supporters waged a campaign and saved the center, but this spring, Schwarzenegger is once again proposing a drastic cut.

Although he has proposed increasing system-wide funding by $97.5 million, Schwarzenegger proposed $3.8 million in cuts from the ILE budget—- the only item the governor vetoed from the UC budget!

Kent Wong of the UCLA Labor Center says the cuts are “a politically motivated attack.” Katie Quan of UC Berkeley adds that the Governor’s attempt to eliminate the ILE without academic review “violates fundamental principles of academic freedom and university governance.”

ILE faculty believe they are a target in part because they are vocal in attacking the pro-business agenda promoted by many state legislators. For example, the UC Labor Center released a study last spring called “Hidden Costs of Wal-mart Jobs.” The Wal-mart Corporation immediately issued a press release, challenging the validity of the study because the Labor Center has ties to unions.

According to a company spokesperson, “It’s disingenuous of the Labor Center’s researchers to tout their study as a fair, balanced assessment of Wal-Mart’s impact on California taxpayers.”

Steve Malanga agrees that labor studies programs stand out for political attacks. He writes in the Wall Street Journal:

It’s easy to view what has happened at labor studies programs as one more manifestation of trends within the academy. But something sets labor studies apart. Unlike gender or race studies, labor studies undeviatingly promote the interests of a tiny constituency: the union. It’s a coup for organized labor to have tapped into the campus culture wars for their own narrow purposes.

As the labor movement struggled to rebuild its power and class consciousness grew on college campuses, a backlash ensued. That backlash has now hit many labor studies programs across the country.

In some cases, labor allies are able to save the programs, but not without a battle that takes a toll. In other cases, university administrators choose not to engage in all-out warfare on the programs, but implement a slow, “death by a thousand cuts” approach.

Yet it seems clear that the budgetary and political attacks have much in common with similar struggles by women’s studies, ethnic studies, Black studies and Chicano studies departments. Faculty and students need to build a broad-based campaign to defend these programs, connecting to related fights to cut tuition, retain or re-institute affirmative action, and decrease the corporate influence in the university.

ATC 118, September-October 2005