Against the Current, No. 118, September/October 2005

-

On to September 24th!

— The Editors -

The NAACP's Future

— Malik Miah -

Muslims in Britain: After the London Bombs

— Liam Mac Uaid -

Solidarity with Iraqi Labor

— Traven Leyshon and Dianne Feeley -

The Message and Meaning of Groundings 2005: Walter Rodney Lives!

— Sara Abraham -

Creating A Movement for Reparations

— Andrea Ritchie -

Economic Crisis & Fundamentalism

— Susan Weissman interviews John Daly -

Kyrgyzstan After Akayev

— Susan Weissman - Attacks on the Academic Left

-

Assaulting pro-Palestinian Activism: Smear Tactics at U-M

— Nadine Naber -

Labor Studies Under Siege

— Stephanie Luce -

Racism & Conflict at Southern Illinois

— Robbie Lieberman - Celebrating the Revolutionary Centenary

-

Rehearsing for 1917: Russia's 1905 Revolution

— David Finkel -

A Hidden Story of the 1905 Russian Revolution: The Unemployed Soviet

— Nikolai Preobrazhenksii -

Rosa Luxemburg & the Mass Strike

— Lea Haro -

Lessons from the 1905 Revolution

— Hillel Ticktin - In Memoriam

-

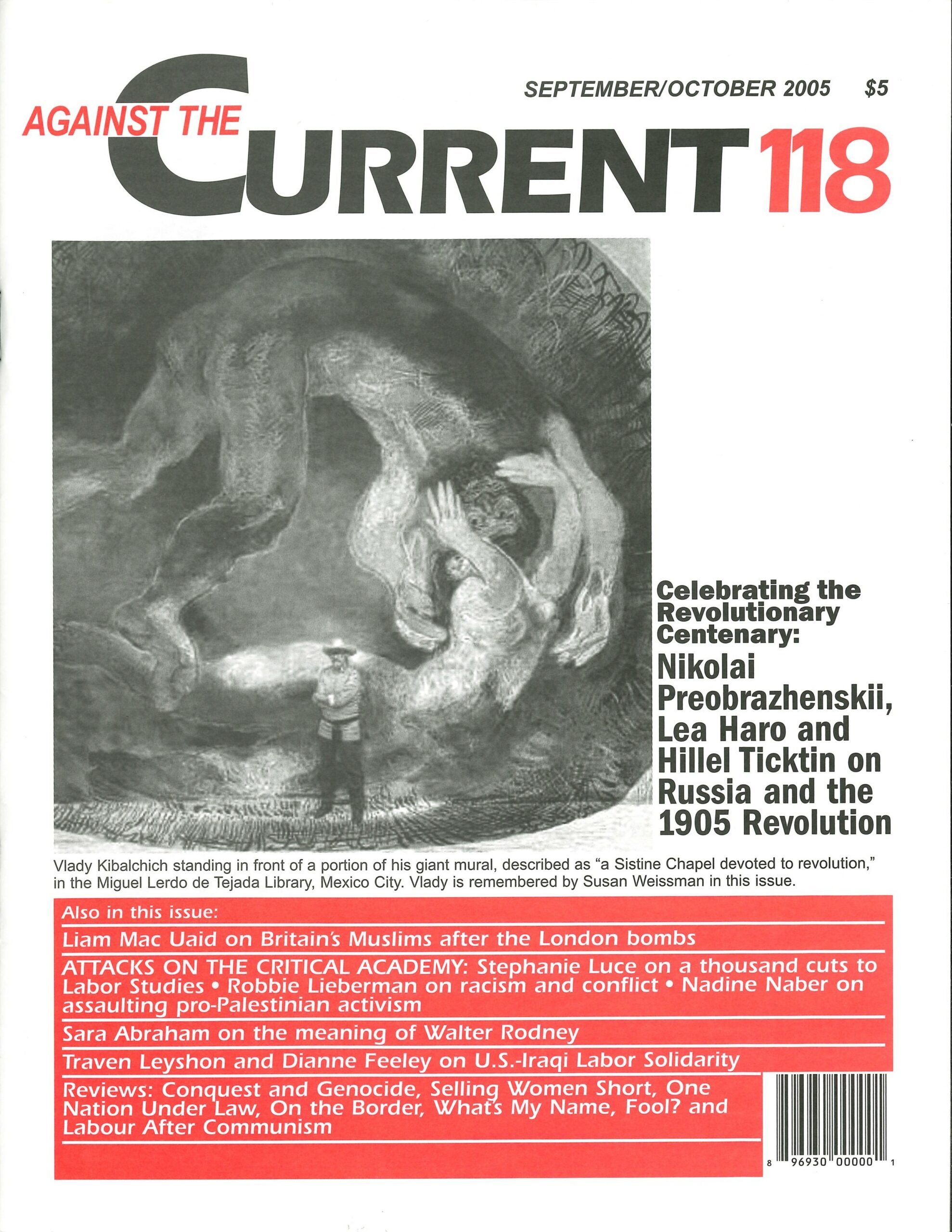

Remembering a Revolutionary Artiist: Vlady Presente!

— Suzi Weissman - Reviews

-

U.S. Law: Religious or Secular?

— Jennifer Jopp -

From the Front Lines of Native Women's Struggles

— Andrea Ritchie -

Fighting the Wal-Mart Plague

— Karen Miller -

Sports & Resistance

— Peter Ian Asen -

An Israeli Anti-Zionist Memoir: On the Border

— Larry Hochman -

Already in Hell: Labor After Communism

— George Windau

Andrea Ritchie

Conquest

Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide

by Andrea Smith

Cambridge, Mass: South End Press, 2005. 244 pages, $18 paper.

AS A LONGTIME Black lesbian feminist progressive who came up through the women’s, anti-racism, labor and environmental justice movements in the United States and Canada, I like to think of myself as fairly well read, and up on my analysis of the historical and current material conditions of women of color and our movements for liberation.

Thanks to Andrea Smith (Cherokee) and her book Conquest, I’ve been schooled to a whole new level about the history of continent I live on, and about the links between the struggles of Native women and my own. As with our understandings of the history and struggles of people of African, Asian and Latino descent in America, much of what we know of the history of peoples indigenous to this continent is informed by male perspectives and experiences of colonization and resistance.

What of our Native sisters? Conquest provides a satisfying combination of historical information, analysis, reflections of resistance, and strategic challenges centered around the experiences of Native women, and with it lessons for all of us who struggle for liberation on this stolen land. Indeed, in the words of Lee Maracle “[e]very single adult human being on this continent needs to read this book. If we did, we all would find the strength to face our history and alter its course.”

Patriarchy and Colonialism

Smith’s wide ranging exploration of the conscious and comprehensive subjugation of Native women as a linchpin of colonialism exposes with brutal clarity the central role of patriarchy and sexual violence in the colonial project. Her book’s greatest strength is the thoroughness with which it reveals, investigates, and links the many fronts of historic and ongoing wars against Native women.

Smith takes the reader on an analytical journey that deepens and broadens our understanding of the manifestations and roles of sexual violence against Native women — from rape of Native women by non-Native men and sterilization abuse of Native women by private and public health officials, to environmental degradation and appropriation of Native spiritualities.

This in turn leads us to expand our understanding of sexual violence as a systemic phenomenon, rather than merely as individual acts of physical violation which serve and reflect broader social power relations. In developing this analysis, Smith makes significant strides in the process of beginning to catalogue the impacts on Native communities of physical, cultural and spiritual genocide — thereby also providing valuable lessons for other communities and peoples subject to historical trauma.

Challenging Assumptions

Centering Native women’s experiences and perspectives leads Smith to courageously and insightfully challenge common assumptions among progressives — be it non-critical stances with respect to current medical research practices and Western medical approaches to infectious diseases; the notion that a pro-choice movement advances the liberation of all women; the proposition that domestic and community violence against women is best addressed through law enforcement and the criminal legal system; the benign nature of what she calls “the non-profit industrial complex;” or the assumption that the continued existence of the United States as a nation-state is assured, desirable or inevitable.

For instance, she notes that “it is a consistent practice among progressives to bemoan the genocide of Native peoples, but in the interest of political expediency, implicitly sanction it by refusing to question the legitimacy of the settler nation responsible for genocide.”

Conquest uncovers the pervasive and deadly hand of the Christian Right throughout the fabric of our society, exposing the manner in which it touches so much more than “hot button” “morality” issues like abortion and the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) individuals.

Indeed, the fiction of the separation of church and state is particularly apparent in Smith’s discussion of Indian Boarding Schools mandated by the state and run by the church to achieve their common goal of “kill[ing] the Indian [to] spare the child.”

Conquest’s analysis of the “pro-choice” movement’s failure of Native women, women of color and poor women is particularly timely as the mainstream, predominantly white feminist movement organizes around another Supreme Court nomination confirmation debate, narrowly focusing on the continued viability of Roe v. Wade. We would be well-served to heed her caution to avoid “the tendency of reproductive rights advocates to make simplistic analyses of who our political friends and enemies are in the area of reproductive rights,” and rather position ourselves to “fight for reproductive justice as part of a larger social justice strategy” which makes “the dismantling of capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism central to its agenda.”

Similarly, Smith’s dissection of the alliances between the mainstream environmental movement and anti-Native sovereignty and anti-immigration forces provides critical perspectives on the role of those who set themselves up as protectors of our dwindling resources in perpetuating the colonial project and their own class interests.

And most relevant in these times, Smith’s explication of the manner in which anti-immigration and “war on terror” policies are an infringement and violation of Native sovereignty is nothing short of visionary. [Editor’s Note: A brief essay on this topic by Andrea Smith, “‘War on Terror’ versus Native Sovereignty,” appeared in Against the Current 105, July-August 2003.]

Smith’s work clearly demonstrates that terror is not just something that happens outside the United States or, if within these borders, at the hands of outsiders and fringe elements. It is an instrument of the American government, used against Native peoples and peoples of color throughout this land and around the world.

Equally critical to the book’s success is its accessibility, achieved without losing any of the complexity of its analysis. It is truly refreshing to read an academic who doesn’t feel compelled to use opaque language to establish her credentials as a movement intellectual.

Indeed, Smith is a true activist scholar — an assistant professor of Native American Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and prolific writer, she is also an energetic and visionary organizer, modeling praxis on a daily basis. As co-founder of INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence and the Boarding School Healing Project, she has put her incisive analysis to work in building broad based movements challenging gender-based violence against Native women and women of color in all its forms.

Colonization Then and Now

Conquest interweaves discussions of historic colonial practices and their present day manifestations, as experienced by Native women specifically and women of color generally. For instance, Smith skillfully links the abduction of Native children, to be incarcerated in government-mandated, church- run boarding schools for the purpose of “civilizing” Native people, to data demonstrating the widespread removal of Native children from their mothers in the present day by the child welfare system, operating under similar presumptions that Native communities and families are “wild,” “unkempt” and “filthy.”

Similarities and differences in the historic and current experiences of Native and Black women, demonized and denied motherhood, are laid out in a way that clearly demonstrates the possibilities for solidarity in action.

In fact, lessons for our collective and individual struggles abound in Conquest. There is something for everyone, be it those involved in the struggle for debt forgiveness which characterized the lead up to the recent G8 meeting; those struggling for environmental justice, education activists fighting the decreasing resources for and increasing criminalization of our schools; or women organizing to end violence in our homes and communities.

Echoes of the historic rhetoric promulgated in furtherance of the genocide of Native people, heralding colonial “liberation” of Native American women from “savagery,” are clearly heard in justifications for the current colonization of Iraq and war in Afghanistan.

Rethinking Freedom and Sovereignty

Throughout Conquest, Smith makes critical links between struggles I had previously seen as being, if not mutually exclusive, disparate enough to require focus on one at the expense of the other.

For instance, while movements for environmental justice and for ending violence against women are clearly both of critical importance to the lives of women of color, Smith creatively and deftly weaves them together by exploring the similarities between the rape of women’s bodies by environmental toxins and through medical experimentation, along and the violation of their beings and reproductive capabilities inflicted by sexual violence.

In so doing she makes concrete the need for a holistic approach that integrates all of these struggles, rather than a traditional ecofeminist portrayal of the Earth as a woman and glorification of the feminine as inherently more “earth friendly” (one need look no further than current Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton or former EPA head Christine Todd Whitman to dispel that myth).

Ultimately Conquest pushes us to dramatically expand the limits of our vision and dream a truly radically different world — to do the hard work of imagining just communities, rather than merely engaging in the relatively easy work of critiquing the world we live in without questioning or challenging its underlying premises, which are necessarily based on the ongoing genocide of Native peoples and people of color around the world.

Smith leads the way by sharing the visions of Native women and women of color, who by virtue of their location as primary targets of the colonial project have little investment in its continued existence, nor in a sovereignty exclusively defined by male dominated nationalistic movements.

Together, Smith and the Native women and women of color whose struggles and visions are reflected in Conquest redefine sovereignty to emphasize interconnectedness, mutual responsibility, and true solidarity between all people and beings.

This heady challenge to break through the limitations of our current struggles to bring about the revolution we want is reason enough to take a journey with Smith through Conquest.

ATC 118, September-October 2005