Against the Current, No. 114, January/February 2005

-

On Oil and Quicksand

— The Editors -

Racist Outrage at UMass-Amherst

— Jeffrey Napalitano, Mishy Leiblum, Barak Sered and Stephanie Luce -

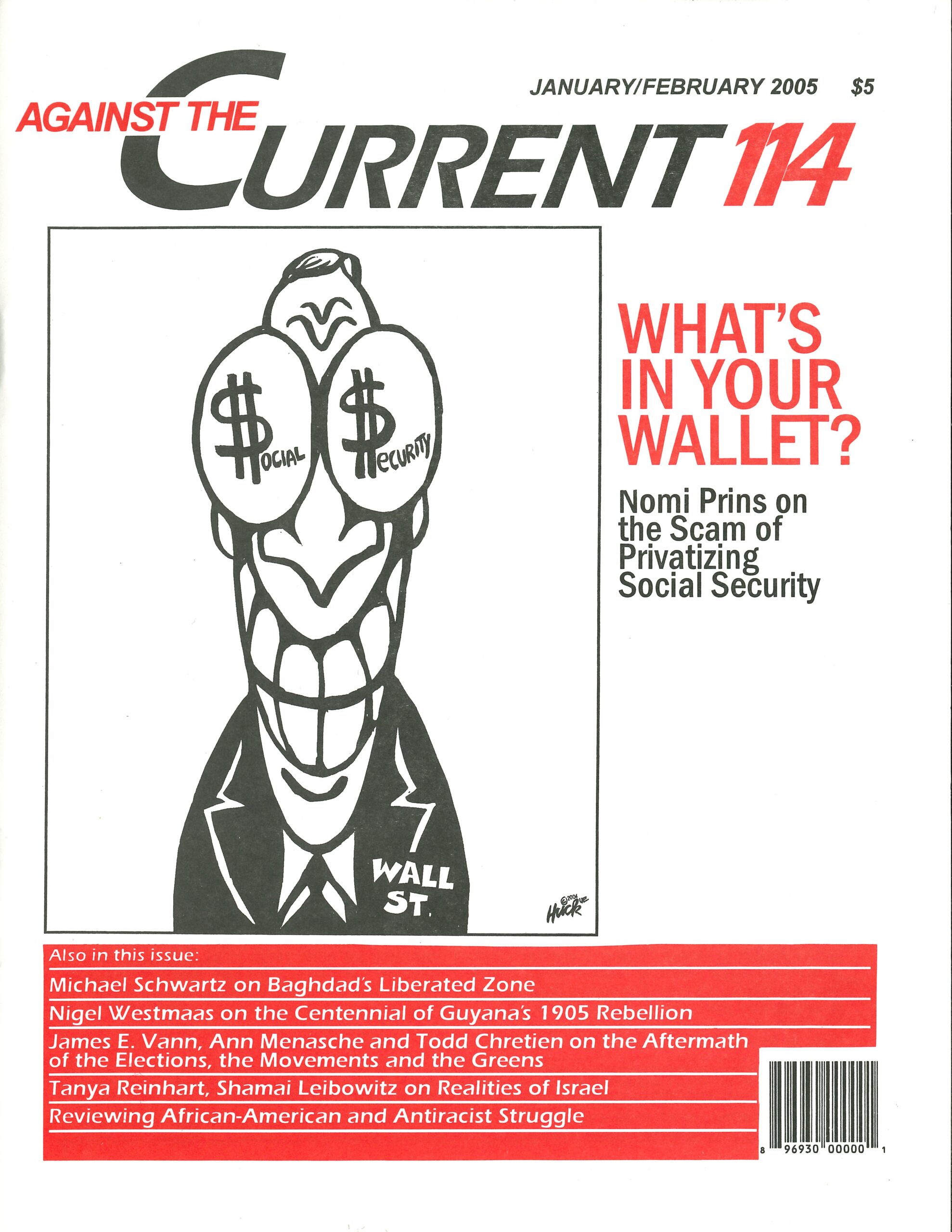

Privatizing Social Security: Who Wins?

— Nomi Prins -

The Dollar's Crisis & the Left

— Loren Goldner -

Grad Student Organizing "19th-Century Style"

— Ursula McTaggart -

Airline Bankruptcies & Workers' Control

— Malik Miah -

Iraq: Guerrilla War in Sadr City

— Michael Schwartz -

Best of Random Shots

— R.F. Kampfer - Celebrating the Revolutionary Centenary

-

Introducing the Year 1905: Centennial of Struggle

— The Editors -

Revolutionary Centennial: Guyana's 1905 Rebellion

— Nigel Westmaas - Israel/Palestine and the Peace Mirage

-

The Illusion of Gaza Withdrawal

— Tanya Reinhart -

In Defense of Divestment

— Shamai K. Leibowitz - US Politics After November

-

After Shock & Gawk

— James E. Vann -

The Democrats' New Scapegoat

— Ann Menasche -

Northern California in 2005

— Todd Chretien - Reviewing African-American and Antiracist Struggle

-

Unwhitening America

— Bill V. Mullen -

Dudley Randall Rediscovered

— Kim D. Hunter -

Caging Race & Gender

— Kristian Williams -

The Prophet Gone Astray

— Peter Drucker - Reviews

-

A Reichstag Fire on Steroids?

— David Finkel -

Another Look at 9/11

— Jack Ceder - In Memoriam

-

Margaret Schirmer Remembered

— Delia D. Aguilar

Nigel Westmaas

“The people are doing nothing. It is the Government who are rioting and shooting down the people.”

—Guyanese worker to British soldier: Guiana Chronicle, 5th December 1905 (1)

1905 WAS A landmark year in the history of Guyana, as it was for several places around the world. In Russia, the Tsar and his troops shot workers delivering a petition in St. Petersburg. In Bengal there were communal shootings; in South West Africa the German massacre of the Herero people was in full progress.

In the British Caribbean, just two years previously, the Trinidad Water Rebellion was characterized by violence and killings, culminating in the burning of the government Red House, symbol of the British colonial occupation. British Guiana (Guyana)(2) in 1905 was no different. The rebellion that year had a dramatic and forceful impact.

Guyana in 1905 was still an important British colony and one of the biggest producers of sugar in the world. Anthony Trollope once characterized it as “a despotism tempered by sugar,” and it was also deemed the “Magnificent Province.” But the colony was now apparently bereft of this Magnificence; excepting the Governor, the wealthy, and the cushioned middle class, everyone was feeling the burden of hard living, partly due to international economic conditions.

By the time the streets exploded in 1905, the background to the rebellion had been well and truly established—a combination of the history of sugar, rice, slavery, indentureship, gold and sweat, commingling and detonating on the streets of the capital city, Georgetown.(3) That now much frowned upon term, the “working class,” was a central component of the body of people taking over the streets at the time.

In the ensuing struggle, according to the national poet of Guyana, there “were some who ran one way, there were some who ran another way/ And I was with them all, I saw a City of Clerks turn into a city of men.” (4)

In this article I will attempt to trace the origins of the 1905 riots, and navigate important aspects of the rebellion’s course and impact in Guyana.

Guyana, like other British colonies, was a place of resistance from the beginnings of slavery. Examples of this resistance are numerous, but the major ones include the great slave rebellion of 1763 (under Dutch rule), the Demerara slave revolt of 1823, the so called Angel Gabriel riots of 1856, the Indian indentured labor riots at Devonshire Castle in 1872, and the 1889 “Cent Bread” riot. 1905 was another link along that historical chain, but made doubly significant by its global implications for the sugar industry.

Guyana was feeling the crush, as sugar made the country and the sugar industry was now plagued with perennial hiccups. In tandem with the fact of an ignorant and repressive Governor and his police chiefs, the desperation in the city slums were ingredients for social explosion. But from what immediate factors did the riot stem?

Historical Background

Guiana, a name for two main slave colonies almost from its inception, shared several colonial “owners” until it was transferred from the Dutch to the British in 1814, and subsequently became united into “British Guiana” in 1831.(5) In 1838, as in the remainder of the British Caribbean, chattel slavery was terminated and new labor regimes implemented with the recruitment of large numbers of Madeiran Portuguese, Chinese, Indian and African indentured laborers.

The change of guard was not total. The expected massive departure from the plantations of enslaved African did not materialize, though many established free villages and garden plots adjacent to their sites of labor. Indeed, so famous were these independent African villages cooperatives that the Times of London famously characterized them in 1844 as “little bands of socialists.”(6) These land movements were eventually suppressed and African Guyanese had to search for alternative means of employment, but many continued to labor on the sugar plantations along with the indentured recruitment from Asia.

By the 1890s the East Indian population had overtaken that of Africans as the largest ethnic group.(7) As of 1900 the main center of the rebellion, Georgetown, formerly Staebroek, was attracting a larger population; apart from being the political/social base of the colonial hierarchy and administrative centers, it was renowned as one of the most picturesque capitals in the region.(8) Georgetown, though composed of a predominantly African base, became quite diverse in population by 1905.

Causes of the 1905 Rebellion

Kimani Nehusi, in assessing the origins of the 1905 rebellion, identifies four main causes: high taxation; low wages; lack of political participation and adequate representation; and the intransigence of the plantocracy in the face of change.(9) All these factors were related in one way or another to the dominance of sugar production in the lives of the people.

There were, however, dreadful international moments for sugar, as in 1884 when the international market for sugar was glutted—a result of stronger economic challenges in sugar (Cuba and Brazil) and the rise of European beet sugar. Sugar nonetheless proved a flexible survivor, even with estates closures, amalgamation and economies of scale.

By the time of the 1905 rebellion large scale diversification in the economy of Guyana was apparent, with East Indians branching out into rice production and forestry, and Africans in the gold fields and with jobs in the urban centers.(10)

The results of the economic changes and monetary dislocations and the social explosions were coming to a boil by the early 1900s. With a slump in worldwide sugar production, gloomy prognoses were in order for the colony.(11) In the event, between 1894 and 1897 there were significant wage reductions of 20-25%.(12)

Wages were already down in the colony, especially for women. In 1905 female cane-cutters were earning as low as 7-8 cents—with the men earning no better at 12-17 cents—per day.(13) The workers at the center of the dispute prior to the riot were not much different in terms of desperation. We can safely conclude, then, that among all the factors leading to 1905, poor wages were the single most incendiary source.

The literature on the actual events and the course of the 1905 disturbances from Guyanese authors is small in quantity and varied in terms of treatment. ARF Webber betrays his anti-working class vibes in his analysis (Centenary History of British Guiana), whereas Walter Rodney (History of the Guyanese Working People) is more detailed in his explication of the social movement and even some of the characters involved in 1905.

Ashton Chase, in providing a sweeping but basic interpretation of the events of November-December 1905, is cautious with his descriptions. He refers positively to the formal strike, of which he approves, and disapprovingly about what he terms the riot. His descriptions betray this bias, with references to “mobs” and “hoodlums” to describe the rioters.

Rodney, by contrast, shows no aversion to the nature of the disturbances and places them squarely in the context of an explosion of the wrathful and indignant working people and unemployed, together with its effect on the colonial authorities. It is always clear on which side Rodney’s scholarship resides.

The 1905 Rebellion

The actual rebellion in Guyana took place between November 28 and December 5. Events began to spiral out of control on November 28th when workers at Sandbach Parker Ltd (the sugar giant) went on strike for more wages. According to Chase, they demanded “16 cents per hour in place of the exiting rates of 48 cents per day for ‘boys’ and 64 cents per day for men…”(14)

The first two days of the strike witnessed its slow spread across sectors, as street activity in support picked up. By the third day, Chase reports that “hoodlums and gangs of work shirkers took matters… out of the hands of the strikers, and by their frequent acts of violence at various wharves on the third afternoon it was plain that the strike had turned into a riot.” (15)

This view of the strike cum riot appears at odds with Rodney’s account of the proceedings. Rodney in essence is much more favorable to the overall trajectory of the rebellion; he does not differentiate between the strike and the riot, and in any case he places responsibility for the violence on the authorities and the repressive arms of the state.

In response to the active presence of workers on the streets the Riot Act was read on 30th November, but not before workers had been shot on the orders of the notorious duo of Her Majesty’s police force, Inspector-General Lushington and Major de Rinzy.(16) The Act read in the center of the city by a Police Magistrate in front of a large crowd did not produce significant movement. Instead of dispersing by order of the Act, the crowds re-congregated in animated groups around the city and discussed the events of the day.

The first of December was the biggest day of the riot, and one newspaper report claimed “three-fourths of the populace of Georgetown seemed to have gone stark staring mad.” (17) Rodney and other historians would disagree with the adjective “mad.”

The people were mad, yes, not “clinically mad” as the phrase seems to suggest, but angry at the authorities and the middle classes that stood in the way of their bread and butter. The above-quoted newspaper report only highlights the contemporary 1900s interpretation of strikes and riots in the colonial world as “eccentric,” because the dominant hegemony was of course colonial.

Rodney’s account of the riot is lively, passionate and descriptive, situating the strike source in the Ruimveldt factory from where grinding of cane began. In his own words, December 1 found the Ruimveldt factory consuming

coals, cane and human labor from 4:00 am. However, work came to a stop by 5:00 am after “Dayclean” cane-cutters joined the factory hands to confront the manager, who not only rejected their wage demands, but sent for the police, alleging that he was assaulted and that the workers were rioting. At 7:55 am, the police and a detachment of artillery were in position on Ruimveldt bridge, over which the east Bank workers were about to cross to link up with Georgetown…the Riot Act was read, and the police opened fire when the crowd failed to disperse….(18)

Historical accounts maintain that thousands came out in response to the shooting. A hostile crowd even invaded the Public buildings, forcing His Excellency the governor to take refuge behind the locked doors in the Court of Policy Hall.”(19)

Female participation in the working-class uprising was significant, and Rodney was far more detailed than any other description of the degree of gender roles in the riot—unearthing evidence from a fairly wide evidential base. As indicated earlier, working women had ample cause to be angry about the colonial wage rates and conditions of life. Their rates of pay were sometimes half that of men, and the conditions of seamstresses employed in the city were compared with “the notorious ‘sweating trades’ of London.”(20)

Indeed the reportage on the activity of women rioters by local and London newspapers went to excess. We learn that the London Morning Post described the rioters as “largely composed of half-civilized Amazons and idle ruffians…”(21) One of these “amazons” reportedly caught the chief repressor, Major de Rinzy, by his throat during the rebellion. (22)

The crowds even stopped horse-drawn carriages carrying persons of European descent, whom rioters saw as closely associated with the owners of the wharves and other businesses. Whenever encountered, they were roughed up and robbed by gangs of workers who also threw stones and bottles at carriages that refused to stop. Other, including three magistrates and the Attorney General, Sir T.C. Rainer, were also chased and beaten by the people.

Later in the afternoon, the rioters moved along Main and High Streets and attacked and looted the homes of Europeans. The police, in an effort to disperse the rebelling crowd, opened fire. When the carnage was over several people were dead, their broken bodies drawn through the city on carts, further inflaming the people.

Ashton Chase reports that by dusk on December 1, “eight persons had been killed and over 30 wounded according to official reports.”(23) But the next day the people came out again on the streets.

The Governor of the colony at the time, Sir Frederic Hodgson,(24) took what Ashton Chase calls “an unprecedented step of addressing the workers.”(25) In classical colonial fashion this was meant as a concession of the unessential, talk; while retaining the essential, the low wage rates and “peace and order.” The same report said that after the governor’s address, in which he promised an inquiry, the people refused to heed his call to disperse but continued to mingle and discuss the strike in groups.

Meanwhile the police “mopping up” operations were described as “swift and brutal,” in which “hundreds of arrests” were made.(26) Identified protesters, mostly male, were whipped and the hair of some rebel women was cut off.(27) The arrival of two British Warships on December 5th, the Diamond and the Sappho and the docking of fresh troops, led to the thinning of the revolt, and placed street power back into the hands of the authorities.(28)

Outcomes of Rebellion

The 1905 rebellion on the streets in Guyana had for a brief moment in time turned the world upside down in this fragment of the colonial empire. It also continued the legacy of militancy of slave resistance and working class protest.

There were several outcomes of the 1905 riot that I can briefly enumerate. As Webber recounts, it eventually led to the constitution of a formal trade union leader and the formation of formal unionizing in the Fabian tradition.

In the very next year, 1906, workers were back in open struggle. Employees at the Bookers and Sandbach Parker wharves in Georgetown went on strike to demand a wage increase from 48 cents to 72 cents a day. Unlike the year before, the workers remained at home instead of gathering on the streets. The strike did not have any significant effect, because both Bookers and Sandbach Parker broke the strike with scab labor including ex-convicts and the reserve pool of unemployed.

Nonetheless, the reforms engendered by 1905 were cumulative and far reaching. In the closing years of World War I, the colony’s first trade union was formed, a definite outcome of the labor battles and riots of the previous decade. The British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU) was established in 1917 under the leadership of H.N. Critchlow. In the act of forming it became the first (formal) trade union in the English-speaking Caribbean.

Born to widespread business opposition, the BGLU at first mostly represented Afro-Guyanese dock workers, but later branched out to represent other ethnic sectors. Its membership stood around 13,000 by 1920, and it was granted legal status in 1921 under the Trades Union Ordinance. Although recognition of other unions would not come until 1939, the BGLU was an indication that the working class was becoming politically aware, and more concerned and active for its members and the working people in general.

Afterwards the reform movement, with contributions from both the working class and middle class, would lead to the emergence of a substantial anti-colonial consciousness whose fruition had to await the formal and significant political organization of the 1950s. 1905, then, was not in vain.

Sources

Chase, Ashton. A History of Trade Unionism in Guyana 1900 to 1961. Georgetown: New Guyana Company Ltd, 1964.

Carter, Martin. Selected Poems. Georgetown: Red Thread Women’s Press, 1997.

Rodney, Walter. A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1981.

Webber, ARF. Centenary History of British Guiana. Georgetown: 1931.

Hazel Woolford, “Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow: the Crusader,” History Gazette No. 43, 1992.

Francis Drakes, “The Causes of the Protest of 1905,” History Gazette No. 22, 1990.

Kimani Nehusi, “The Causes of the Protest of 1905,” in McGowan, Rose & Granger. Themes in African Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998.

Notes

- Cited in Walter Rodney, History of the Guyanese Working People 1881-1905, 200.

(back to text) - “Guyana” will be used throughout the article for British Guiana. Guyana became independent in May 1966.

(back to text) - The issue of what term to use to describe the events of 1905 bedeviled the author. “Riot” is considered a pejorative colonial description, whereas “rebellion” was more positive. Walter Rodney nonetheless used “riot” freely, but positively, to describe the proceedings. I generally use the term “rebellion” for the sake of caution.

(back to text) - Martin Carter, Selected Poems. Georgetown: Red Thread Women’s Press, 1997.

(back to text) - Prior to the merger in 1831 Guyana was divided into two territories, Demerara-Essequibo and Berbice.

(back to text) - Walter Rodney, 128.

(back to text) - By 1911, according to published statistics, East Indians had become the clear dominant population group in the country. See History of Guyanese Working People, Appendix, 240.

(back to text) - Staebroek was renamed Georgetown in 1812.

(back to text) - Kimani Nehusi, “The Causes of the Protest of 1905,” in McGowan, Rose & Granger. Themes in African Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998.

(back to text) - In the 1890s there was a veritable gold rush, and many African laborers went to interior locations to seek the lucrative gold seams.

(back to text) - Francis Drakes (Kimani Nehusi), “The Causes of the Protest of 1905,” History Gazette, July 1990.

(back to text) - Alan Adamson, Sugar without Slaves.

(back to text) - Francis Drakes, op. cit., 7.

(back to text) - Ashton Chase, 20-21.

(back to text) - Chase, 21.

(back to text) - All the descriptions suggest that these two were anathema to the crowds and repressive on their own account.

(back to text) - Ashton Chase, 22.

(back to text) - Rodney, op. cit., 192.

(back to text) - ibid.

(back to text) - Rodney, 206.

(back to text) - Rodney, 207.

(back to text) - Rodney, 214.

(back to text) - Ashton Chase, 22.

(back to text) - This Governor was also known for his repression in the African colony of the Gold Coast (Ghana) and once even demanded that the sacred Golden Stool of Asante be brought for him to sit on. See Rodney, 213.

(back to text) - Ashton Chase, 23.

(back to text) - Ashton Chase, 22.

(back to text) - ibid.

(back to text) - The HMS Sappho was a cruiser of 3,400 tons and had 272 men on board. HMS Diamond held 300. Troops from these vessels were used to arrest the leaders of the strike. (Rodney, 194)

(back to text)

ATC 114, January-February 2005