Against the Current, No. 105, July/August 2003

-

What the Airline Crisis Shows

— The Editors -

"War on Terror" versus Native Sovereignty

— Andrea Smith -

Old and New War in Aceh

— Kurt Biddle -

France, Chirac and Bush's War

— Sophie Beroud and Patrick Silberstein -

The New Strike Wave

— Sophie Beroud and Patrick Silberstein -

A Voice for the Irish Left Wing

— Tommy McKearney -

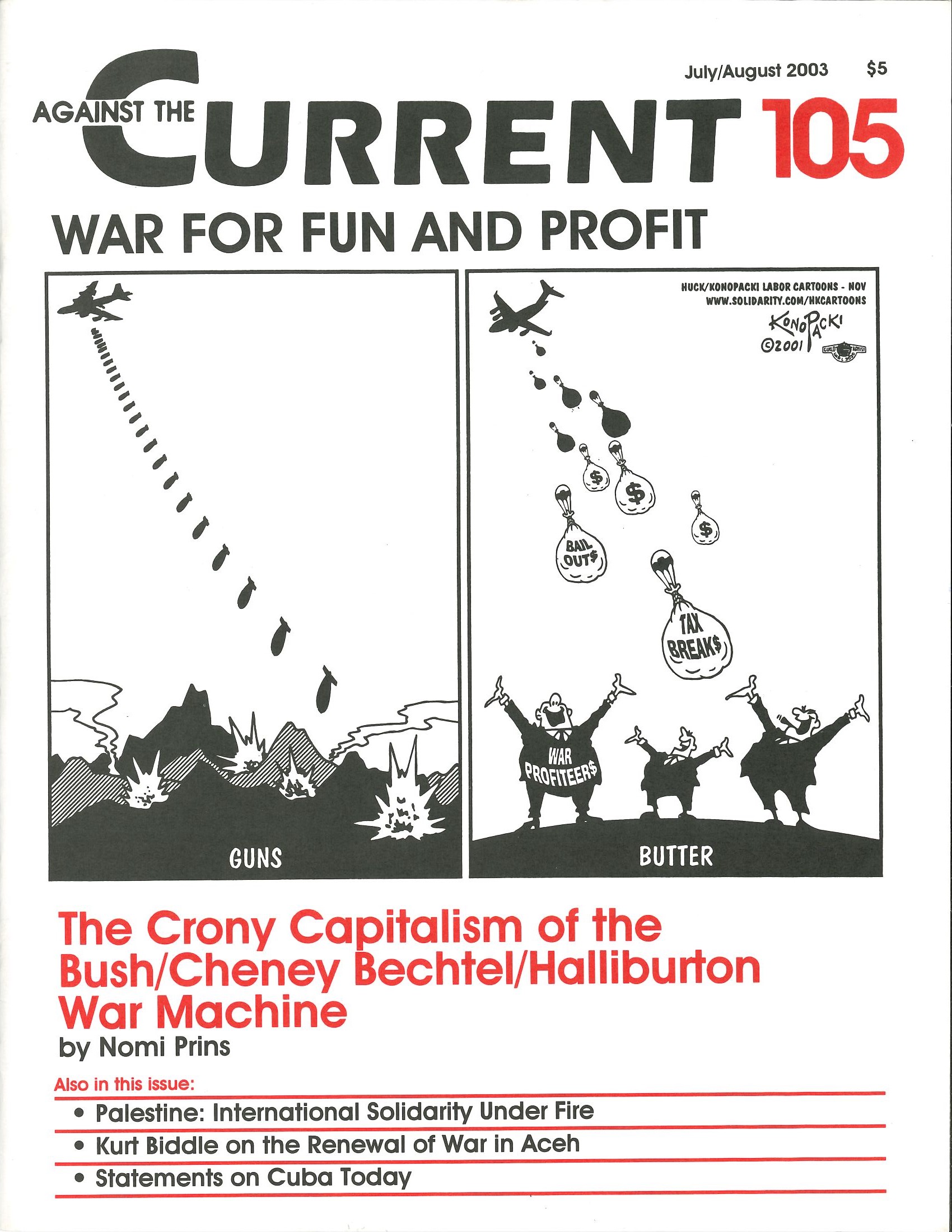

Inside the Crony Wars

— Nomi Prins -

From Lynching to Lethal Injection

— Jan Boudart -

Random Shots: Iraq and a Hard Place

— R.F. Kampfer - The International Solidarity Movement

-

Confronting the Occupation

— David Finkel -

The Israeli Army Shot My Brother

— Sophie Herndall -

Our Humanity in the Balance

— Carel Moiseiwitsch, Gordon Murray and Drew Penland -

One Day in Ramallah

— Daniella, ISM volunteer -

Palestine: Dying for Peace

— Louisville Middle East Peace Delegation - Discussing Cuba

-

An Introduction

— The ATC Editors -

To the Conscience of the World

— a statement initiated by 10 prominent Mexicans -

A Statement by Solidarity

— Political Committee of Solidarity -

A Fourth International Statement

— Executive Bureau of the Fourth International -

Stop Bush's New Aggression Against Cuba

— statement initiated by the International ANSWER Coalition -

Oppose Repression in Cuba

— statement published by the Campaign for Peace and Democracy -

Why the Cubans Acted Now

— Joaquín Bustelo -

Cuba Makes Me Hurt

— Eduardo Galeano -

This Is Where I Get Off

— Jose Saramago -

Cuba: We Know, and So What?

— Alain Krivine - Reviews

-

Rebel Pens, "Pencil Hands," and Labor Journalism

— Steve Early -

The Lost Art of "Scottsboro" in Linoleum Cuts

— James A. Miller -

Judith Ezekiel's Feminism in the Heartland

— Sonya Huber -

Tanya Reinhart's Israel/Palestine: How to End the 1948 War

— David Finkel - In Memoriam

-

Julius Jacobson (1922-2003)

— Samuel Farber -

Michael Kidron (1939-2003)

— Samuel Farber -

Nina Simone: And She Meant Every Word of It!

— Kim D. Hunter

James A. Miller

Scottsboro, Alabama:

A Story in Linoleum Cuts

by Lin Shi Khan and Tony Perez

edited by Andrew Lee

New York: New York University Press, 2002, 147 pages, $26.95 cloth.

THE NOTORIOUS SCOTTSBORO case of 1931 — nine Black youths falsely accused of raping two white women on a freight train moving through northern Alabama — became an instant national and international cause.

In less than two weeks after their arrests, the Scottsboro defendants were tried and convicted by all-white juries in the mountain town of Scottsboro, Alabama, and eight sentenced to death. Aroused by the close attention given to the case by the American Communist Party and the International Labor Defense, an organization founded by the CP in 1925 to defend “class war prisoners,” public reaction was immediate and forceful.

Mass demonstrations broke out in the United States and in countries throughout the world. A six-year legal battle over the fate of the “Scottsboro Boys,” as the defendants came to be called, led to two landmark Supreme Court decisions: Powell v. Alabama in 1932 and Norris v. State of Alabama in 1935.

The Scottsboro case also inspired an outpouring of political chants, agit-prop skits, songs, poems, full-length plays, film scripts, fiction, political cartoons, and art. To this incredibly rich literary and artistic legacy of the Scottsboro case can now be added Andrew Lee’s discovery of 118 linoleum prints about the case.

Lee, the Tamiment Librarian at New York University and a graduate student in its History Department, came across these prints in the personal library of Joseph North — a well-known Communist journalist and critic during the 1930s and editor of its important magazine New Masses — whose papers now reside at the Tamiment Library as a gift of his family.

Even in their original condition — linoleum prints glued on to aged construction paper, with water damage and mold on the binding — the visceral power of these images was easy to discern. With the assistance of the Preservation Department of the NYU library, Lee was able to restore these images and preserve them in their original order.

Forgotten Artists

In spite of Lee’s best efforts — and astounding as it may seem — we know virtually nothing about the two artists, Lin Shih Khan and Tony Perez, who created the prints, except that they were produced sometime in 1935.

At that time the Scottsboro case was still winding its long, arduous and sometimes bizarre trail through the legal system, ongoing demonstrations, and complicated behind-the scenes maneuvers of the various parties involved in the case.

We know that the prints were produced in the Old Howard Building in Seattle, Washington and bound with a foreword by Mike Gold, a founder and editor of New Masses and widely regarded as the “cultural commissar” of the left during the 1930s.

Gold, who had clearly seen the prints, praised them as “another rivet in that skyscraper of a new art that we are building in our time, an art that has come out of the mepthitic (sic) bourgeois studio, and into the streets and fields where the masses live and struggle for a new and better world.”

Yet they were apparently never mass-produced or distributed; Lee speculates that the bound prints were sent to New Masses and somehow wound up in Joseph North’s personal collection.

A World of Upheaval

How do these images illuminate their historical moment — and our own?

Robin D.G. Kelley’s Foreword provides an overview — albeit sometimes with very broad brush strokes — of the Scottsboro case as a world historical event precipitated by the direct intervention and mass mobilizations of the International Labor Defense.

Kelley locates the case squarely within the context of the revolutionary upheavals of the decade following the Stock Market collapse in 1929: the rise of Facism in Italy and Nazism in Germany, Japanese imperialism in Asia, and the stirrings of civil war in Spain.

He also links the Scottsboro case to revolutionary stirrings in the United States, particularly the militant organizing efforts by the American Communist Party in the aftermath of the 6th World Congress of the Communist International in 1928, when it adopted the slogan “Self Determination in the Black Belt.”

Kelley seems particularly concerned to link the Scottsboro case to other forms of class struggle in the South, most notably the shoot-out between police and members of the Alabama Share Croppers Union in Tallapoosa County, Alabama in July, 1931 — an event that came to be known as the Camp Hill shootout.

Kelley depicts Scottsboro, in other words, as symptomatic of the larger struggle for racial and social justice, much of it waged by still unacknowledged Black workers and sharecroppers in the South.

Call to Action

Andrew Lee’s Introduction returns our attention to the images themselves, reminding us that they were produced in 1935, two years before the first break in the ordeal of the Scottsboro Boys, when four of them were released as a result of back-door negotiations with Alabama liberals and state officials.

Lin Shi Khan and Tony Perez unequivocally align themselves with the tradition of politically committed lithography established by Honore Daumier in the mid-19th century, using strong, bold lines and minimal text to issue both a sharp critique of social injustice and a rousing call for decisive political action.

Their intentions are clearly to place the plight of the Scottsboro Boys in the broadest possible historical perspective, providing along the way graphic illustrations of the structural underpinnings of racism and social injustice in the United States.

Hence, the opening Edenic image of a nuclear family in Africa — over which hovers the threatening figure of a serpent, symbolic of the slave trade that both disrupts African life and launches the African-American epic.

The first section of this tripartite narrative, “The Negroes Come to America,” quickly leaps from a graphic image of the interior of a slave ship to one of plantation slavery to a startling and powerful image of African-American rebellion in the form of an agricultural worker who has broken his chains.

In this rapid-fire and compressed fashion, the viewer is quickly brought face-to-face with the forces that have conspired to block African-American aspirations for freedom and justice: the “bosses,” who organize the Ku Klux Klan and who rule by intimidation and terror, supported by public officials and the courts.

Against this backdrop, these images dramatize the transition in Black life from chattel slavery to wage slavery — this bringing the lives of Blacks into close propinquity with those of white workers, who suffer from similar misery and deprivation.

The potential for alliances being formed on the basis of these shared experiences is underscored by one of the last scenes in this section of the book: “At Camp Hill Negro and White Toilers Gathered To Draw Up A Bill of Rights,” a meeting disrupted by the “bosses” and the omnipresent forces of terror.

Political Shadings

The narrative of Scottsboro, Alabama is shaped, in short, not only by the immediate political urgencies of arousing public sympathy for the Scottsboro Boys in the mid-1930s, but also by the left politics of the mid-1930s.

Khan and Perez assign a central role to the Communist Party in the ongoing drama of the Scottsboro struggle — rightfully so since, in retrospect, it seems clear that without the efforts of the Party, nationally and internationally, the Scottsboro Boys would likely have been executed.

But there are interesting glitches and anomalies in the narrative, too. There is no reference, for example, to the fight between the Scottsboro Boys and the white youths on the train that really precipitated the episode; the white boys simply disappear from the story as other victims of the railroad deputies, who run them out of town.

The narrative goes to some lengths to emphasize that Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, the two white women whose testimony sealed the conviction of the Scottsboro Boys, shared the same socioeconomic plight as the boys themselves — thus effectively placing the onus of the verdict upon the “bosses,” the newspapers, and particularly the courts.

It excises any mention of Alabama Judge James Horton, whose courageous decision to overturn the second conviction of Heywood Patterson in 1933 cost him his judgeship. And the narrative concludes with a line from Trotsky’s The History of the Russian Revolution -– “into the ash heap of the bitter past” — hardly language that orthodox Communists would endorse.

But this is just another way of saying that, in the final analysis, the power of Scottsboro, Alabama depends less upon its historiography or grasp of details and more upon the graphic images themselves, and in the passion the artists bring to the text and demand of their readers — their insistence that their critique of American racial practices is fundamentally sound, and that concerted mass struggle across racial boundaries is the most effective way of challenging and defeating this history.

In this respect, Scottsboro, Alabama still has the power to inspire anger and outrage — and to remind us of a political legacy that still has relevance for the 21st century.

ATC 105, July-August 2003