Against the Current, No. 96, January/February 2002

-

Whose Rights Are Sacrificed?

— The Editors -

Police Riot, Drama Builds in Mumia Case

— Steve Bloom -

The New Politics of Argentina

— Francisco Sobrino -

Peru from Fujimori to Toledo

— Al Twiss -

Martin Luther King: Christian Core, Socialist Bedrock

— Paul Le Blanc -

Random Shots: Pirates, Gladiators and Assassins

— R.F. Kampfer -

Introducing Arne Swabeck

— Christopher Phelps -

Why Did the Socialist Party Decline?

— Arne Swabeck - Afghan Women's Long Struggle

-

Women for Freedom

— Tahmeena Faryal -

Afghanistan's 25-Year Tragedy

— an interview with Tahmeena Faryal -

Give Us Back Afghanistan!

— Sharifa Sharif - Views on the War and the Crisis

-

U.S.-Israel Sow the Wind

— A Statement by the ATC Editors -

Our Enemy Is at Home

— Malik Miah -

The Rebel Girl: Liberated for Real?

— Catherine Sameh -

A War or A Lynching?

— Edward Whitfield - Reviews

-

Milton Fisk's Toward A Healthy Society

— Jeff Melton -

Transforming Teacher Unions

— Joel Jordan -

Different Rainbows, Third World Queer Liberation

— Gary Kinsman

Steve Bloom

DECEMBER 18, 2001—U.S. District Judge William Yohn threw out Mumia Abu-Jamal’s death sentence, but refused his request for a new trial. The state of Pennsylvania was ordered to conducrt a new sentencing hearing within 180 days. If that does not take place within the time frame outlined, Mumia will, according to Yohn’s ruling, be sentenced to life in prison.

In a 272-page decision Judge Yohn upheld Mumia’s 1982 conviction on first-degree murder charges. But the ruling could be appealed to the U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals. The prosecution has already announced it will appeal, seeking to reinstate the original death sentence.

But even if Yohn’s decision is upheld by higher courts, the state could still seek to impose the death penalty at the new sentencing hearing.

Police Riot

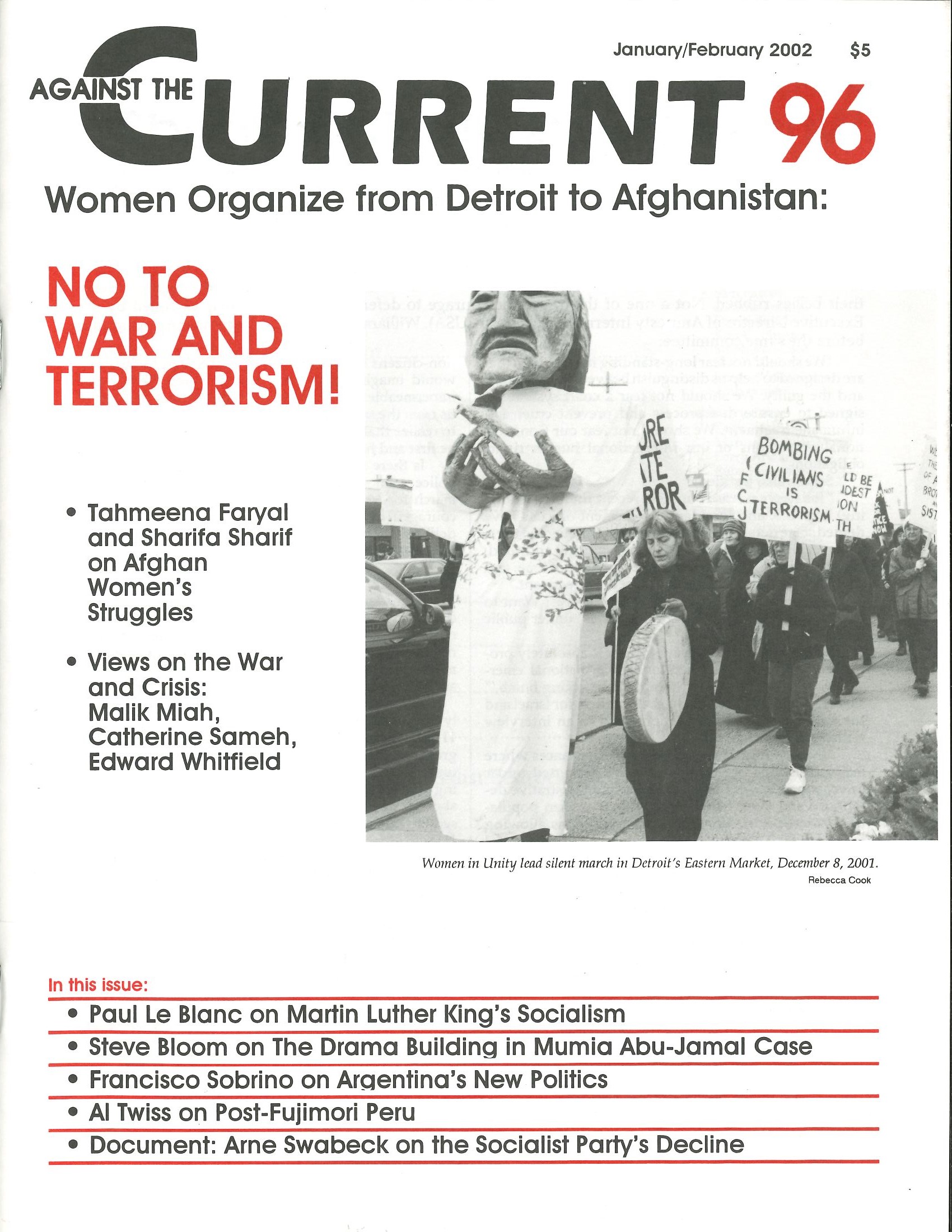

On Saturday December 8, one day before the 20th anniversary of the events in 1981 that led to Mumia Abu-Jamal’s arrest and conviction for murder, a peaceful demonstration of around 1000, demanding that new evidence in the case be heard in court, was attacked without warning or provocation by Philadelphia police. A number of protesters were arrested and several were hospitalized with serious injuries, including one concussion, a fractured tailbone, internal bleeding, and a broken jaw.

Six of those arrested have been charged with felony assault and felony riot, as well as conspiracy, assault, and conspiracy to riot. However, video and photographs taken at the scene, as well as multiple eyewitnesses, tell a different story.

In a message sent out the day after the attack, International Concerned Family and Friends of Mumia Abu-Jamal stressed that they had a permit for the march. Ordinarily, during demonstrations in Philadelphia, there are civil affairs police who are supposed to act as a liaison between the authorities and protesters—a system which has regularly been in place at past Mumia demonstrations. According to witnesses the civil affairs police were nowhere to be found during the police rampage on December 8.

Last spring Mumia, the former Black Panther and prize-winning journalist who will soon enter his twenty-first year on Pennsylvania’s Death Row, fired his former attorneys and hired a new legal team.

Since that time developments in the case have unfolded rapidly, beginning in early summer when a confession by Arnold Beverly was filed with the federal court, along with a number of supporting affidavits (see ATC 93, July/August 2001).

Then at the end of August, Mumia’s lawyers submitted a new affidavit by Terri Maurer-Carter, a former court reporter who has now come forward to testify that while Mumia’s original trial was going on in 1982 she overheard Judge Albert Sabo announce, “I’m going to help them fry the nigger.”

Judge Sabo’s prejudice against Abu-Jamal has long been a legal issue in this case, but until now it could only be inferred based on his behavior as documented in the court record. Now there is direct testimony making things explicit.

New evidence also continues to emerge in relation to the confession by Beverly, who says he is the one who shot and killed Police Officer Daniel Faulkner back in 1981—the crime for which Mumia was convicted and sentenced to death.

According to Beverly he and another hit man were hired by the mob because Faulkner was interfering with the graft and corruption that was rampant among Philadelphia police at the time (designed to guarantee the safety of those who operated gambling and prostitution rings in the city).

There is considerable independent corroboration of this official corruption, such as a federal investigation and indictment of Philadelphia cops—including one who participated in the “investigation” which led to Mumia’s trial. And previously known evidence of how “incompetently” the investigation into Faulkner’s death was carried out lends further credibility to Beverly’s statement about actual police complicity in the murder.

For example, no attempt was made at the scene of the crime to establish whether Mumia’s gun, the alleged murder weapon, had been fired, or to check his hands for gunpowder residue. Both of these simple forensic tests are standard in a murder investigation involving firearms.

At the same time that Beverly’s confession was filed with the courts there was another affidavit introduced, by Linn Washington, a reporter for The Philadelphia Daily News. Washington said that when he visited the crime scene the next morning, only hours after Faulkner was shot, there had been no attempt to cordon it off, and no police officers were standing guard—again, two routine procedures in any murder investigation, especially when a policeman is the victim.

Legal Struggle on Two Tracks

Many questions remain about Beverly’s confession. But clearly it is in the interests of justice for this witness to be examined in a court of law, where the statements in his affidavit could be cross-examined.

Beverly provides considerable detail about what happened on the night of the shooting, corresponding with known facts or statements by other witnesses previously on the record. Mumia’s attorneys have filed papers in both federal and Pennsylvania state courts asking that a formal, legal deposition of Beverly take place.

This would constitute sworn testimony, with the same legal standing as statements made in a witness box during a trial. As part of the deposition process the prosecution, which claims that Beverly’s statements are unbelievable, would be able to test his knowledge about what happened on December 9, 1981, through a thorough cross examination.

If Beverly is lying they should be able to easily show that he is not aware of facts which the real killer would surely know, and that his confession is therefore a fabrication. Yet the prosecution has opposed allowing a deposition and has asked the courts not to consider Beverly’s statements at all.

Federal District Judge William Yohn has already ruled that, at least for now, he will not permit a deposition of Beverly. His reasoning is that Mumia’s legal petition, filed by his former attorneys in October 1999, is based on errors that took place during Mumia’s original trial—and does not actually assert that Mumia is innocent of the crime for which he was convicted.

The confession by Beverly is relevant only to an actual claim of innocence, and therefore Yohn cannot consider it as part of the proceedings currently before him. Yohn has noted, however, that Mumia’s new attorneys are requesting to amend this previous petition, and if he allows the amendment (which he is not required to do) he could reconsider the question of admitting Beverly’s evidence.

In a parallel proceeding, Mumia has also asked the state courts to reopen his Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) proceedings—previously concluded in 1998—so that Beverly’s testimony, and other new evidence such as the statement by Terri Maurer-Carter, can be considered.

This request was heard by Judge Pamela Dembe. Aware of the importance of new legal developments, thousands mobilized outside Judge Dembe’s courtroom with only a few weeks’ notice on Friday, August 17, when she held an initial hearing on the defense petition to reopen the state PCRA appeal.

The day before Thanksgiving Judge Pamela Dembe refused Mumia’s request, basing her decision on strictly technical issues involving time limits applicable to the introduction of new evidence. She asserted that she had no jurisdiction to decide anything substantive.

Dembe’s ruling can be appealed, but the available appeal—aside from a request that she reconsider her own findings—is to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, the same court which upheld all of Judge Albert Sabo’s rulings in the original PCRA process.

Time Limits and the EDPA

In federal court the prosecution is also arguing that legal time limits for introducing Beverly’s testimony have expired.

Beverly’s confession was known to the defense as far back as 1999. Mumia’s former attorneys chose not to bring it forward, and the prosecution is arguing that Mumia thereby defaulted on his right to ask that this evidence be heard in court.

Both the Effective Death Penalty Act (EDPA), passed in 1996, and state law regarding the PCRA process set time limits on how quickly new evidence must be presented once it is discovered. But the law also provides for exceptions, and Mumia’s attorneys have filed papers making a legal case that the exceptions should be applied here.

As Marlene Kamish, one of the current team of attorneys, pointed out: “If there is no statute of limitations on murder, how can there be a statute of limitations on a confession of murder?”

Further, it should be clear that any legal process designed to pursue justice cannot allow Mumia to be executed without even considering Beverly’s confession now that Mumia has asked for it to be heard.

This point, combined with a legal argument based on international treaties which supersede the EDPA, is made strongly in a letter, sent by the International Association of Democratic Lawyers and received by Dembe prior to her ruling:

“When advised of this fresh evidence as well as other newly discovered information that supports Abu Jamal’s exoneration, the Philadelphia District Attorney is arguing that the Pennsylvania Courts have no jurisdiction to schedule a hearing for the presentation of this exculpatory testimony and other evidence that supports Mumia Abu Jamal’s innocence, as if there were a statute of limitations on evidence which can prove the innocence of someone on death row.

“In the face of this new, never previously available evidence, any refusal by the Pennsylvania Courts to review Abu Jamal’s conviction will constitute a gross violation of internationally recognized standards of due process including Article (14) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. To condone the execution of an innocent man by excluding newly found exculpatory evidence because of alleged procedural technicalities would violate inter alia Article (6) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Article (4) of the American Convention on Human Rights; the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“The United States, like other members of the United Nations, is expressly bound by the legal provisions of the Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and is also a signatory bound to the provisions of the American Convention on Human Rights.

“Additionally, international standards can be considered in the interpretation of the United States Constitution through Article VI. Indeed, the U.S. Supreme Court has expressly recognized that International Law is part of United States Law. It has been determined that such Treaties to which the United States is a party are binding on the states through the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

“It is the considered and reasoned belief of the members of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers that, for justice to be done and seem to be done in this case, the Pennsylvania Courts must grant Mr. Mumia Abu Jamal’s petition and schedule hearings to consider the testimony of Arnold Beverly and all other exculpatory evidence now available.”

Ongoing mobilizations needed

Aware of the importance of new legal developments, thousands mobilized outside Judge Dembe’s courtroom, with only a few week’s notice on Friday, August 17, when she held an initial hearing on the defense petition to reopen the state PCRA appeal.

The December 8 protest was called before Dembe ruled, but later took on the character of a protest against her decision. Speakers and participants pledged to continue the struggle to ensure that the courts to hear the new evidence in the case. Among the participants was a delegation of elected officials from France, who reported that the Paris City Council had recently granted Mumia the title of honorary citizen. The last person so honored, in 1971, was the artist, Pablo Picasso.

Steve Bloom is the author of Fighting for Justice: The Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, an activist handbook published by Solidarity

from ATC 96 (January/February 2002)