Against the Current, No. 92, May/June 2001

-

"This Changes Everything . . ."

— The Editors -

Quebec City: Gas Against Democracy

— Betsy Esch -

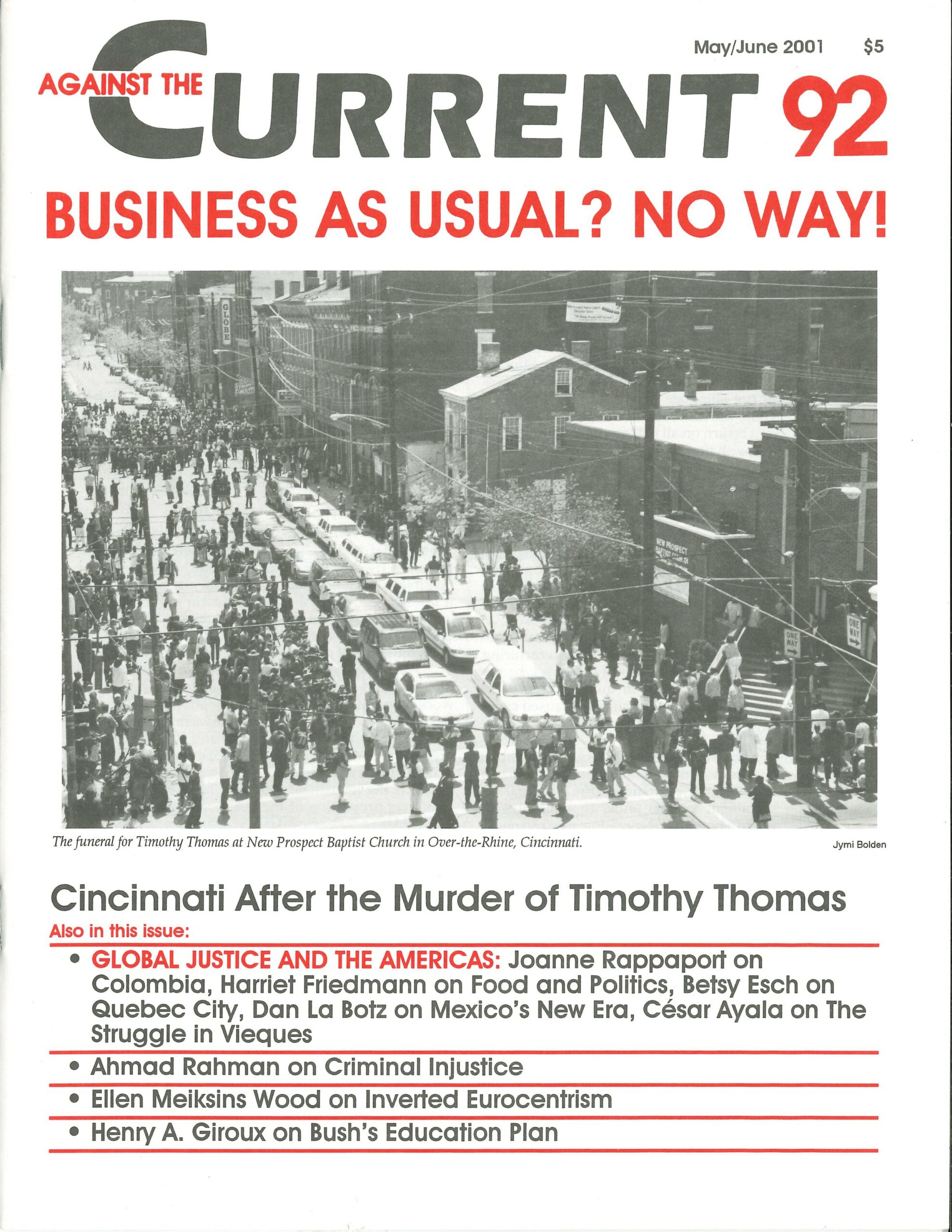

Cincinnati After the Uprising

— Dan La Botz -

Responding to David Horowitz

— Douglas Taylor -

A System of Criminal Injustice

— Ahmad Rahman -

Actions for Mumia May 11-13

— Steve Bloom -

Palestine Up Against the Empire

— an interview with Noam Chomsky -

Vieques and U.S. "Democracy"

— César Ayala -

Colombia: Options from the Grassroots

— Joanne Rappaport -

Indonesia: Confronting Military Violence

— Kurt Biddle -

Mexico's New Political Era Begins

— Dan La Botz -

Stop the Murders!

— SOS Initiative -

The Struggle for Genuine Unions in Mexico

— David Bacon, Joan Axthelm, and Daisy Pitkin -

Global Justice, What We Eat, Who We Are

— Sara Abraham interviews Harriet Friedmann -

Leaving Most Children Behind

— Henry A. Giroux -

Eurocentric Anti-Eurocentrism

— Ellen Meiksins Wood -

The Rebel Girl: Salute OUR Final Four!

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Tender Loving Care

— R.F. Kampfer -

Radical Rhythms: On Ken Burns' "Jazz"

— Kim D. Hunter -

Letters to the Editors, on C.L.R. James

— Marty Glaberman; Alex LoCascio - Reviews

-

20th Century Black Nationalism

— Clarence Lang -

The Politics of Islam, Indonesia's Ruling Elite and Democracy

— Malik Miah

Joanne Rappaport

ON WEDNESDAY OF Easter week, 500 hooded paramilitary gunmen invaded the hamlet of Rio Mina in the region of Naya, Cauca, and three nearby villages. By the time the massacre ended, thirty-three villagers had been murdered in front of their families, and more than 500 terrorized survivors fled. (El Tiempo, April 16, 2001) Horrifying accounts like this one have fuelled extensive criticism in the U.S. press and in alternative publications regarding “Plan Colombia.”

This U.S.-sponsored program aims at restoring order to that South American country and halting the flow of drugs to the north, through extensive fumigation of coca and opium poppy fields in the southern part of the country and a counterinsurgency program focused against FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), the major guerrilla organization operating in this Andean nation.

For the most part, the press has not been sympathetic to the Plan Colombia, whose major component is military assistance to an armed forces mired in human rights abuses and in collaboration with the paramilitary organizations that have burgeoned in the past year.

They also criticize the Plan Colombia because it does not address in an effective manner the structural problems which have given rise to the Colombian conflict: economic crisis, poverty, corruption, rule by an oligarchy, pervasive violence.

One of the most recent and most insightful of these articles is Marc Cooper’s “Plan Colombia: Wrong Issue, Wrong Enemy, Wrong Country” (The Nation, 19 March, 2001).

Cooper provides a thorough but concise explication of the history of the various parties to conflict and the dangers of the Plan Colombia. He also presents a highly perceptive analysis of a guerrilla movement with little mass support, thus refocusing the conflict for North American readers who might otherwise have viewed FARC as similar to the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) in El Salvador or the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) in Nicaragua during the 1970s and `80s.

Such publications have done an excellent job at providing us with clear arguments as to why the United States should not get involved in a war in the Andes. But few writers have examined alternatives to Plan Colombia, beyond urging U.S. support to the peace process, which has unfolded in fits and starts over the past two years — but is increasingly viewed in Colombia as an unattainable goal, given Colombia’s deep economic and political crisis and the lack of participation by civil society in the government/FARC dialogue.

This article will consider alternative proposals to the Plan Colombia by looking at developments in the southern part of the country, the region in which the Plan’s military and fumigation efforts are focused.

The View on the Ground

The central and northern parts of Colombia are more well known than the south. Here lie most of Colombia’s major industrial cities, such as Bogotá, Medellín, and Barranquilla, serving as magnets for an ever-growing flood of rural migrants from a countryside that has become increasingly impoverished.

The southern departments of Caquetá, Cauca, Huila, Nariño, Putumayo and Tolima, in contrast, are still highly rural in character, with Afrocolombian, indigenous, and mestizo peasants making up the bulk of the population.

Although southern peasants have increasingly acquired land through participation in colonization projects in the lowland regions of Caquetá and Putumayo, and through successful ethnic land claims movements in the highland departments of Cauca, Huila, Nariño and Tolima, rural economies have faltered with the high prices of chemical fertilizers and the lack of effective marketing networks for peasants to sell their produce in urban areas at a price that would permit them to support their families.

Some Colombians say that the two-hour ride from the major city of Cali to Popayán, the capital of Cauca, is like a “time tunnel” through which the traveller moves back into the nineteenth century, to a region of landed elites and peasant serfs.

But Cauca is very much a product of modernity. Here indigenous peasants, like their counterparts in the other southern departments, do the only thing they can to hold on: They grow coca and poppies, thus inserting themselves into a clandestine global market very much of the twenty-first century.

Drug cultivation has posed insoluble problems for these communities. While poppies and coca bring in needed cash, they also deplete the soil and replace needed food crops, aggravating malnutrition in communities which have become increasingly dependent upon store-bought food that is less nutritious than the products they once cultivated.

The indigenous community of Toribío, for instance, counts only some 30% of its agricultural production in food crops; the remainder is equally divided between coffee and drugs, neither of which can be eaten by its residents.

In regions of paramilitary control such as the municipality of Buenos Aires, where six thousand Afrocolombian and indigenous Nasa peasants were displaced in late-December by the AUC, the paramilitary umbrella organization, peas<->ants are not permitted to transport more than a scant $30 U.S. of food market per day by paramilitary operatives trying to block provisions to guerillas. Here the replacement of food crops with illicit crops would indeed be a recipe for disaster.

Communities are increasingly fearful of confrontations between armed actors, not only because of the massacres that these battles bring and because the paramilitary take their lands to redistribute to their supporters, but because they dread the possibility that vital roadways will be closed, blocking the provision of foodstuffs to their inhabitants.

Indigenous Organizing

In my own experience of following indigenous communities in Cauca over the past decade, I see little support among them for either the guerrillas or the paramilitary, and even less for the Colombian army, which has always been viewed as an aggressor, thanks to the Colombian elite’s long opposition to Cauca’s ethnic movements.

In contrast, reservation councils have striven to organize their members in support of community institutions and struggles, while Nasa shamans are increasingly performing rituals to protect their populations against the army, the guerrillas, the paramilitary and the police — as well as against North American fumigation efforts, which have destroyed the food crops, poisoned their water sources, and left lands barren and sterile among the Guambiano, Nasa, and Yanacona ethnic groups.

All of the armed actors have committed human rights violations in indigenous communities, perpetrating massacres, murdering indigenous authorities, opposing peasant struggles against landlords and agribusiness, and forcibly recruiting youth to their ranks.

Buenos Aires, the home of the thousands displaced in December, is a region where in the 1980s FARC killed peasant leaders organizing against the encroachment of Cart<162>n de Colombia, a large paper company, upon their lands, and where today, AUC has targeted the population to punish them for their activism. The army and police also have a long history of murdering indigenous and peasant leaders, frequently through pájaros, or hired assassins.

None of the armed groups respects the self-determination of the communities, leading Cauca’s regional indigenous organizations, the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC) and the Movement of Indigenous Authorities of Colombia (AICO), to publish a vehement rejection of the presence of these armies in their territory. FARC has targetted CRIC’s leadership, as well as the reservation councils of Toribío and San Francisco, with threats aimed at countering the organizations’ repudiation of the presence of armed actors on indigenous soil.

FARC and AUC both nevertheless continue to use Cauca and the rest of southern Colombia as a battleground, a strategic corridor for access to the coast, and in the face of a lack of popular support, have bought adherents for the equi>alent of $300 or $400 U.S.

Development for Whom?

Southern Colombia has become a magnet for economic development, generally aimed at promoting agribusiness and tax-free industrial zones. In Santander de Quilichao, Cauca, where a vast zona franca has grown in the past five years, bringing almost all its workers from urban areas to the north and hiring few locals, industrialists and owners of sugar cane plantations and large cattle ranches have been accused of support for the paramilitary.

Former governor of the department of Chocó, Afrocolombian leader Luis Gilberto Urrutia, worries that Plan Colombia will bring further development of large-scale African palm production, instead of working to promote community development in conjunction with Afrocolombian and indigenous organizations.

Yet in southern Colombia, so impoverished and so beset by violence and conflict, a real alternative to the quagmire of Plan Colombia is being posed.

Coalitions of indigenous and peasant organizations, labor unions, marginal urbanites, and progressive sectors of the academic community have come together in the past year. Working in concert with politically independent municipal mayors and some departmental governors, they are calling for regional dialogue in which broad sectors of society engage in negotiation with the state and with armed actors, and they are opposing Plan Colombia’s fumigation objectives.

A recent visit to Washington by four governors, of the departments of Cauca, Nariño, Putumayo and Tolima, sponsored by U.S. human rights organizations, has begun to alert North Americans to the grassroots possibilities that we could support in our efforts to block Plan Colombia.

One of the governors, Floro Alberto Tunubalá, former governor of the indigenous reservation of Guambía and former indigenous senator in Bogotá, was elected by such a broad coalition, which grew out of mass mobilizations demanding government compliance with previous accords that had promised basic social services to native and peasant communities. Tunubalá and his cabinet, like his CRIC colleagues, have received threats from armed actors: he reports that he is on the death lists of both AUC and FARC.

Grassroots Action

In June 1999, twelve thousand indigenous demonstrators blocked the Panamerican Highway for eleven days at a site called La María, a Guambiano reservation, effectively cutting Colombia in two and isolating the regional center of Popayán and cities to the south.

The demonstrators organized to pressure the government to recognize the major indigenous organization, CRIC, as a traditional authority akin to reservation councils, as well as to make good on earlier promises to promote land reform, expand rural health systems and to support bilingual education through spending for teachers.

Negotiations with government representatives at La María were open and democratic. The atmosphere that prevailed was a combination of political convention and religious pilgrimage, with the active participation of shamans. But there was also an element of high moral purpose: The indigenous people of Cauca were once again showing the nation as a whole that they were a force to be taken seriously, and not a historical memory.

The demonstrators at La María were also intent upon forcing FARC to respect the indigenous movement. Busy attacking the nearby town of Caldono, FARC wished to take advantage of the situation and launch an attack upon Popayán, but they were run out of the camp by the unarmed demonstrators, who refused to raise FARC’s objectives above their own political demands.

In November of the same year, when it became clear that the government would not come through with its promises, CRIC once again organized its forces in concert with peasant leaders from CIMA, the Committee for Integration of the Colombian Massif, closing the Panamerican Highway for twenty-five days to the north and south of Popayán and virtually cutting off the city from the outside world.

This mobilization was broad-based and involved the participation of upwards of fifty thousand people, protesting the government’s failure to deliver on its promises to the Massif zone, the most abandoned region of Cauca. After the government acceded to peasant demands, signing another agreement, the idea was born of creating an interethnic space in La María, where various groups could coordinate and integrate their mutual concerns.

La María was constituted on October 12, 1999 as a Territory of Coexistence, Dialogue and Negotiation, a site at which those left out of the Colombian state’s peace process could exercise popular democracy.

La María became a site for workshops to train grassroots leaders, a place for negotiation between popular organizations and the government, a stage for popular assemblies, and a mechanism for developing the institutional framework and discourse needed for effective confrontation.

At La María, multiple issues have been discussed, including the implementation of the agreements signed as a result of the two mobilizations that preceded its foundation; careful consideration of the economic, social, and cultural rights of victims of violence; proposals for agrarian reform; and demands and projects related to preserving biodiversity in Cauca.

La María, which has survived on a shoestring budget with small financial contributions from a trade union in Switzerland and the Dutch Embassy in Bogotá, has also become the site of dialogue with visiting delegations, such as a group of Italian politicians, in order to ask them to bring pressure on the government to comply with the social agreements that had been signed.

Education and Reconstruction

La María has also become a critical site for discussions among popular organizations about the dangers and challenges posed by the Plan Colombia. Here, local activists have participated in workshops aimed at educating them about the dangers of fumigation of illicit crops.

As an alternative to the U.S.-supported fumigation program, grassroots leaders, who are indeed cognizant of the harm that such cultivation has caused in their communities, have begun a program of advocating manual eradication by community-based organizations and subsequent implementation of local plans for economic and social reconstruction.

An example of this policy is evident in Guambía, the reservation from which Cauca’s governor Tunubalá hails. Here, the reservation council sought the assistance of hundreds of volunteers to uproot virtually all the poppies grown there, thus strengthening community institutions by encouraging mass participation by reservation members.

As an alternative to poppy cultivation, a Life Plan, developed over the past decade by the community, was implemented. The Life Plan is much more than a development plan, given that it aims at mapping the community’s welfare over more than twenty years in areas from economic reconstruction, to bilingual education, to culturally-sensitive provision of medical services.

The Plan also projects from the past, by using historical research by Guambiano intellectuals as a basis for analyzing where the community should be moving in its future development.

This sort of linking of community aspirations to anti-drug activities which strengthen community institutions is precisely what the four governors who visited Washington support, in contrast to the Plan Colombia.

In their vision, negotiations with the state and with armed actors, which must take place at the regional and grassroots levels and not just between FARC and the national government, must also be accompanied by far-ranging planning by grassroots activists who, in an atmosphere of democratic dialogue, can chart the futures of their communities.

This project, and not the military provisions of the Plan Colombia or its social components, is the alternative posed by southern Colombian activists and their independent political representatives.

ATC 92, May-June 2001