Against the Current, No. 79, March/April 1999

-

Women Rising, Then and Now

— The Editors -

Movement Grows to Save Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Steve Bloom -

Race and Politics: Blacks in Corporate America

— Malik Miah -

Putting the Fox in Charge: What's Fair About the Fair Labor Association?

— Medea Benjamin -

The Future of Israel and Palestine

— Harry Clark interviews Professor Israel Shahak -

Hugo Chávez and the Crisis of the Dependent Countries: Nationalism, Populism & Democracy

— Guillermo Almeyra -

Random Shots: Sic Transit Gloria Bunny

— R.F. Kampfer - The Teamsters: From Carey to Hoffa

-

Why Junior Won-and What Next?

— Henry Phillips -

The Election's Broader Impact

— Mike Parker - For International Women's Day

-

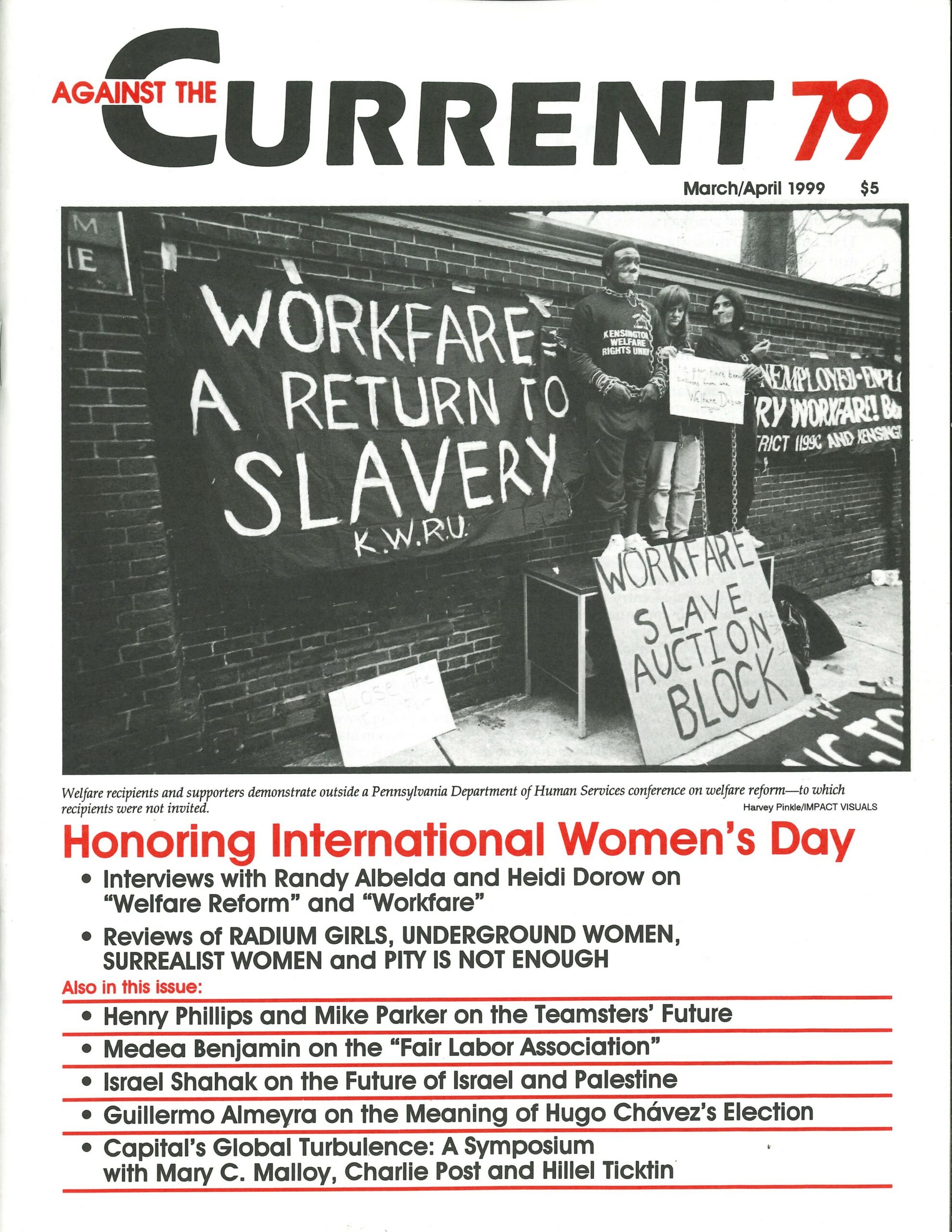

The Misogyny of Welfare "Reform"

— Stephanie Luce interviews Randy Albelda -

NYC's Workfare Shell Game: An Interview with Heidi Dorow

— The Editors -

Claudia Clark's "Radium Girls"

— Dr. Sherry Baron -

Review: Memoirs of An Underground Woman

— Rachel White -

Josephine Herbst's "Pity is not Enough"

— Angela Hubler -

Review: Recovering Surrealist Women

— Bertha Husband -

The Rebel Girl: Death of Our Hoop Dreams

— Catherine Sameh - Capital's Global Turbulence: A Symposium

-

A Reply to Robert Brenner

— Mary C. Malloy and Charlie Post -

Accumulation and Control of Labor

— Hillel Ticktin - In Memoriam

-

Joyce Maupin, 1921-1998

— Barri Boone

Guillermo Almeyra

Translators’ Introduction.

OIL-RICH VENEZUELA, HISTORICALLY one of Latin America’s more affluent countries, has been in an economic crisis since the `80s. More than half the population is estimated to live under conditions of poverty, and what was once a significant middle class has been shrunk under the impact of the crisis. The austerity policies imposed by the International Monetary Fund have played a major role in this process of impoverishment and provoked, in 1989, the outbreak of massive popular protest and street disturbances in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital. These disturbances were repressed by the government led by President Carlos Andrés Pérez, a very corrupt social democrat who acted as the enforcer for the ruinous policies of the IMF.

The social democrats of Acción Democrática (AD) have alternated in power with the Christian Democrats of COPEI ever since the overthrow of the military dictatorship of Marcos Perez Jimenez in 1958. By the ’90s this arrangement had neared total exhaustion as both parties became implicated in growing corruption and were, to put it mildly, unable to offer any sort of alternative to the deep economic crisis affecting the country.

It was in this context of social and political decay that Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez, a left-wing military nationalist and populist, attempted a coup d’etat in 1992 against Carlos Andrés Peréz. The coup failed and Chávez spent several years in prison. Once released, Chávez entered the political arena—and was elected President of Venezuela with a substantial majority of the vote in the elections held in December of last year.

Chávez’s electoral campaign was definitely radical in content and included a set of promises and demands clearly opposed to the interests of the native ruling classes as well as to those of U.S. imperialism. Among these it is worth noting the pledge to suspend payment of the foreign debt, nationalization of public transport and electricity, considerable expansion of welfare state programs, limitation of ownership of apartments and houses to two per family with any excess to be expropriated for the purpose of redistribution to the homeless, government- directed occupation of idle lands by the population, and in case of hunger provoked by an economic blockade, a government-directed expropriation and distribution of existing business inventories.

However, Chavez’s program also included the quite worrisome if not alarming demands that women are no longer to work outside the home since they should dedicate themselves to the home and to the raising of children, expulsion of illegal aliens and a forceful suppression of neighborhood delinquency, if necessary with the use of firing squads.

At the time of this writing, Chávez has taken office with a far more moderate posture than the above program would suggest. It remains to be seen whether this constitutes a temporary tactical retreat or something more permanent. The article by Guillermo Almeyra should be of considerable assistance in helping us to make sense of this situation.

THE SMASHING ELECTORAL triumph of Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez, previously imprisoned because of his participation in a failed military coup against the government of Venezuelan President Carlos Andrés Pérez provoked diverse reactions and much confusion.

Some observers tore their garments and lamented the “depolitization” of the Venezuelan people (although the electoral turnout broke all records) because they saw the triumph of a former putschist with no party as a blow against democracy, which for these observers meant a political party regime and a Constitution.

Others, on the contrary, held that the people were already in power and that consequently everything was going to be solved with a Savior, an enlightened nationalist, who would bring Venezuela out of its crisis and backwardness.

This reopened the discussion concerning the relation between parties and movements, between nationalism and democracy, and between formal democracy and substantive democracy in society at large. The following article attempts to deal with some of these questions.

It is evident that nationalism is always dangerous and creates an opening to chauvinism. And the populism of military men, educated to give unchallenged orders, also contains elements of fascism.

Such elements include the love of “order” imposed from the heights of the state, or the decision to establish a direct contact with “the masses,” short-circuiting discussion and institutional mediations that serve both as barriers to the arbitrariness of decision makers and as democratic political mediations, which are schools for building a political society.

Also, the present process of globalization and the full crisis of modernity calls into question certainties and ideologies, including the very ideas of progress, democracy, socialism and rationality in social life. Regionalisms and nationalisms of every type burst out in the open, and political ties based on the cult of personalities and pure faith also develop.

These go beyond the classic figures of the Ibero-American caudillos of varying political tendencies (Primo de Rivera [founder of the fascist Spanish Falange] or Franco, Perón or Fidel Castro), and differ from the leadership types of politicized societies with clear class structures.

The Bases for a New Populism

We live today in an era of populism: the U.S. right-wing and its leaders, the Northern League in Italy, the French or Austrian neofascists, and on the opposite political pole Lula in Brazil, Cárdenas in Mexico, the leaders of the Argentinean Frepaso (a political front coming out of the left-wing of the Peronista party) and, to a certain extent, Subcomandante Marcos. These tendencies share a theoretical confusion, a primitive manicheism and a prepolitical morality, dressed with a neosocial Darwinist sauce or with neodependentism, according to tastes and latitudes.

The theoretical mist and confusion, or rather the cloud of dust provoked by the inglorious and precipitous collapse of the so-called “real socialism,” prevails. For many, this was not only socialism but also a model, and others even identified it with Marxism, now declared buried under the debris of Stalinism.

It is therefore logical that mass political phenomena do not assume “pure” forms (if they ever did) and nowadays unite within themselves not only contradictory but also opposed expressions and tendencies.

The early Perón arrived to power with a labor-type party formed by the unions and supported by a series of bureaucratic union leaders of anarchist, socialist and communist origin. But the early Perón simultaneously surrounded himself with the exiled Ante Pavelic, the genocidal Croatian Fascist leader, pro-Franco ideologists, extreme right nationalist chauvinists of the Alianza Libertadora, and right-wing and fascist priests.

That was in 1946, when the old colonial powers were collapsing and the United States did not yet occupy the world stage as it did later in the fifties. It is therefore not surprising that in the current hegemonic crisis of the United States and of world capital, there is a political vacuum that is being filled with atypical figures, especially in the abnormal dependent capitalist countries, ill-named “emergent” (which should be called, instead, “submergent”).

The Peculiar Latin American Nationalism and Populism

Different phenomena converge in the nationalism and populism of dependent countries, particularly those led by the military. One, historical, is the fracturing of the apparatus of domination in every period of great social crisis.

The military of criollo [native white] origin (San Martín in South America and Allende in Mexico among hundreds of lesser known cases), and the mid-level priesthood (Fray Luis Beltrán in the River Plate, Murillo in the Peruvian Highlands, Hidalgo and Morelos in Mexico, among others) broke with the colonial power and struggled for independence.

Such conflicts erupted not only due to the fracture provoked in the monarchy by liberalism, but also because every period of socio-economic crisis is also characterized by the ideological and political crisis and by the fracture “among those at the top,” as well as between the top and the bottom.

This fracture in the armies and in the army of the Lord, which is the Church, has re-emerged in this century affecting the predominance of those two apparatuses of domination. This has been accompanied by the crisis of the apparatus of cultural domination, meaning the intellectuals, which in our backward capitalist countries still assumes the primitive form of the political and moral weight of the intelligentsia, nonexistent in Western Europe (except for Greece, pre-Franco Spain or Portugal), or in the United States.

Thus, in Latin America, Brazil experienced tenientism (“lieutenantism”) in the ’20s and the “comunist” military putschism of 1935, Bolivia had its Radepa (Razón de Patria, Reason of the Homeland), which helped the unions bring the MNR to power in 1952), Argentina its MOU (Movimiento de Oficiales Unidos, Movement of United Officers) which led to the Ramírez-Farrell-Perón coup of 1943, Chile its Socialist Republic with Colonel Marmaduke Grove and its populist dictatorship under General Ibáñez del Campo. Bolivia had its General Juan José Torres and the Popular Assembly, Peru its Velasco Alvarado.

In Brazil, Admiral Cándido Aragao and the marine gunmen resisted the 1964 coup, Mexico underwent its henriquismo [the movement in support of the non-official candidacy to the presidency of General Henrique which was bloodily suppressed]. In Cuba military men participated in the uprising against Batista, along with, but separately from, the barbudos (bearded rebels).

Pinochet murdered not one but two of his supreme military commanders (Schroeder and Prats) along with many other officers throughout the armed forces. In Guatemala there were several uprisings, Yon Sosa’s among them, and in Guatemala and El Salvador military men became guerrilleros. Panama had its Torrijos and his disciple, Noriega.

The Catholic Church (although by no means only in Latin America) underwent a similar process: The Brazilian gorillas [right-wing military rulers] were forced to repress the Helder Cámaras and Frei Bettos, those in Peru the Gonázlezes. In Argentina it is impossible to count the dead among the seminarists and priests opposed to the dictatorship of the military followers of the Opus Dei.

Liberation Theology was born and developed particularly in this continent and the opposition to fundamentalism and religious conservatism had, just to mention its better known archbishops, its Casaldaligas in Brazil, its Méndez Arceos in Cuernavaca, its Romeros in El Salvador and its Ruizes in Chiapas.

The second phenomenon is a sociological process, given that the lower and mid-level intellectuals (including the group of very peculiar intellectuals who are in contact with the people, that is the priests and the military) serve the dominant classes but are despised and badly paid by the latter. Also, in their desire to ascend the social hierarchy, they violently clash against the shameless luxury and the social violence of the traditional landowner oligarchy or the dominant bourgeois sectors involved in exporting capital and in international financial capitalism.

These latter sectors also are cosmopolitan, antinationalist and anti-national and hurt the nationalist feelings and the search for native roots of the middle sectors who seek national development independent of the imperial power.

Thus, the nationalist education imparted to the “defenders of the homeland” and the universalist culture of the Church clash with the comprador bourgeoisie and the servants of the international finance capital. This collision produces a fertile field for the break from neoliberalism, the ideology of capital nowadays.

In other words, these processes lead the most sensitive elements of the lower intellectual strata to reject the concrete values of capitalism although they are not capable of proposing an alternative.

The Economic Engine of Populism

There is also an economic factor at work here: The priests and the military, except for the Navy or the “noble” arms such as the Cavalry, are recruited in our countries from the poorest sectors of the population, who send their children to the barracks or to the seminaries in order to provide them with food and with an education [Chávez himself is the son of a worker and was sent to the army in order to obtain a higher education].

The poor send their children to those places expecting a degree of social mobility which is blocked by the social structure of their own countries. They thus find themselves watching the banquet of the ruling classes without being able to satisfy their hunger.

During the periods of economic crisis, these low-level officers and priests watch the increasing void in their wallets along with the rest of the people including the poorer sectors of the middle classes, while those in power safeguard themselves through outright theft.

Because of their social origins, the priests and the military are pushed to become the receivers of the popular protest that reaches them directly given their location in the social fabric (in every small town there is a church and a military outpost which puts them in daily contact with the deepest strata of the urban and rural working people).

To this we must add an important political factor: The determining sectors of the ruling classes are no longer nationally rooted nor nationalist. They export their capitals and form part of international financial capitalism, they have the culture of the cosmopolitan jet set, are formed in foreign universities, are contemptuous of their own countries where they would have rather not been born and which they rob without any remorse.

By being part of financial capital, they don’t even have clientelist ties with national political life. Financial capital forces the states to abandon part of their functions and empties the content of decisions by the parliaments which are, in any case, weak and without power.

The rulers increasingly become technocrats of international capital, and less and less political mediators among the national classes. They turn their backs on their own countries.

The crisis leads the ruling elites to delinquency, to international drug trafficking and to corruption as a way of compensating for their short lived relevance and political duration, since they are unable to think in terms of national development nor of reducing the friction among classes and regions given that funds for those purposes are not available.

In this manner, they merge their private interest with their public positions and power, abandoning any pretense of public service. The republican sentiment of the middle classes, their morality, their contempt for thieves, their desire for justice clash with the globalization of the ruling groups and provoke, as a reaction, a wave of nationalism with a heavy social content.

But in these countries, the previous dominance of the oligarchies and the present control of international finance capital has for decades prevented any democratic experience.

The political parties and the other instruments of mediation, such as the bureaucratized unions, have lost credibility—not only because of the process of globalization, the so-called “end of ideologies” and their corruption and conservatism, but also because they have sunk themselves in institutionalism and integration in the state machine precisely when these institutions (parliamentary or otherwise) count for less and less, and when the state has lost many of its fundamental functions in the face of the imperial “governance” of U.S. tools such as the IMF and the World Bank.

Meanwhile, part of the left has given up on the search of any alternative to capitalism in the name of a “realism” which leads it to accept a “more generous” liberalism, and a criminal policy “but without excesses.”

In this manner, the partial vacuum opened by the loss of hegemony of the United States is joined by an ideological and political national vacuum, which opens the road to movements—not parties—of a new and greatly confused form where solidarity is personalized.

The experience of the peasants in the rural areas is joined with that of the popular neighborhoods and rank-and-file union groups to create the elements of a new plebeian leading group, with strong caudillista inclinations. That type of personalized solidarity is just one among a number of visible forms of popular resistance which includes working-class and popular self-organization.

This is exemplified by the strong participation of students and workers in Chávez’s coup against Carlos Andrés Pérez, the continuous strikes by students and workers and their radicalization during Caldera’s government [independent Christian Democratic President of Venezuela immediately prior to Chávez], the rank-and-file rupture with MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo), with leaders who came from Acción Democrática and with former socialists, communists, guerrillas and oppositionists, all of whom participated in Calderas’ right-wing populist government under imperialism’s thumb.

The overwhelming popular and working-class support of Chávez was a result of a molecular, subterranean process of discussion, shaping of opinion, organization of decision-making and conscience-forming, a weaving of popular organizational threads.

It is worth mentioning that Chávez’s triumph against the media campaign demonstrates, against those who think that people have empty or wax brains on which the mass media stamp whatever imprint they wish, that the public and official culture stands apart from the culture of the dominated classes, even though the culture of the dominated is, at another level, that of the ruling classes.

A Potentially New Process

The isolation and rupture among the decisive classes, which ends the fiction of “national unity” (thus making more difficult reactionary populism), and the rupture in the apparatus of domination or repression (churches, army) indirectly points to the existence of a new process not only in Venezuela but in the whole of Latin America.

The great crisis of 1929-30 developed mass movements (Cardenismo in Mexico, pre-Perónist movements in Argentina, the Brazilian movements, the Popular Front of Aguirre Cerda in Chile, the Cuban uprising against Machado, etc.) and originated modern populism (Lázaro Cárdenas’ paternalism and statist corporatism, but also its anti-imperialist nationalism).

The crisis of the imperial powers during World War II unleashed in the more important Latin American countries (Brazil, Argentina) the desire to take advantage of difficulties elsewhere in order to develop their own national bourgeoisie and an internal market, and even to obtain a role as a minor power (as Perón wished). Since the national bourgeoisie was too weak or too linked with the imperial powers, the Army and the State tried to substitute for it, and in its turn to form it and give it a voice.

In the absence of nationalist bourgeois classes and given the political isolation of corrupt technocrats in the service of international finance capital, the present political, economic, social and moral crisis creates again the temptation to replace what once was the national bourgeoisie, dependent on the internal market that has almost disappeared, with technocrats of a different type.

The new actors are the technocrats of power, the military, who compensate for the lack of a party with their “party” in uniform, and for their lack of ideas with a nationalist – populist – christian – socialist collage.

Given that the Latin American military, in spite of their strength, are not in the political, economic, and moral conditions to overcome the crisis by openly taking power (they have to hide behind such people as the Peruvian Fujimori), there is now a possibility that military discipline will decline with the growth of politicization and discussion in the barracks everywhere.

The bases for populist nationalism increase to the degree that globalization puts into question the ideas of the nation state, national identity and cultures, and provokes social movements of resistance to denationalization and to capitalist exploitation and social oppression.

Such a populism could adopt the form of the Young Turks [after Kemal Ataturk’s movement in the aftermath of World War I] for the XXI century, with modernizing and moralizing intentions, or of support to non-revolutionary democratic and nationalist politicians such as Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas in Mexico.

Such populism could join Liberation Theology (analogous to the military who countered native to Spanish virgin saints during the struggles for independence) to develop a non-Marxist and popular ideology and get the support of the peasant and marginal sectors. Or, under certain conditions, it could even lead to a coup by a minority of low-ranking or non-commissioned officers, such as the Cuban sergeants in the thirties who, disgusted by “democratic” corruption, raised Batista to power as a renovator with popular support.

In contrast with the capitalist industrial countries, in the dependent countries populism can develop a subversive nationalist anti-imperialist version because the struggle for national independence is, at the same time, the struggle against the domination of the centers of world capitalism.

For that reason, even though populism in the “periphery” contains the same ingredients as those of nationalist populism in the metropolitan countries, it does not have them in the same genetic order or in the same proportion. Over there you have Newt Gingrich, Silvio Berlusconi, Le Pen, the Greek colonels; over here you find the Hugo Chávezes.

The Present Crossroads

We don’t know the script for the coming events. But what is certain is that the economic, political and moral crisis is going to get worse, that the ruling classes have no alternatives to this crisis, do not offer any future or have any credibility.

We know that there is a multiform popular resistance that is trying to organize itself and raise the banners of justice, freedom, social change even though it may not know how to impose these. The crisis mobilizes and breaks all the apparatuses of the state, and particularly its principal base, popular consensus. The only sure thing is that everything is in movement.

That is the base for Chávez. If he submits to the imperial power and that of the dominant classes, if he makes mistakes or major stupidities because of his nationalism or political primitivism, if those in power sink him or not, or if they convert him into a Caribbean Saddam Hussein after they fail to integrate him, is in the last analysis a secondary question. The important thing is not Chávez but the processes that have brought forward Chávez.

The rest depends on the Venezuelan people in its relation to Chávez, which is not only a relation of dependence, and on the new President himself, who has before him various options and could convert himself into a Bolívar, Perón, Torrijos or Bucaram [former populist President of Ecuador overthrown by an alliance of popular protest and the traditional right].

This also depends, of course, on the international support for the independent option that Venezuela seems to face, and on the critical independence of those who should know how to separate the processes, which should be supported, from each one of the decisions made by transitory leaderships. This requires, in other words, a political secularism that the left should learn to achieve in order to be something more than the crowd who, from the circus bleachers, whistles or applauds the gladiators.

Mexico City, January 7, 1999

ATC 79, March-April 1999