Against the Current, No. 69, July/August 1997

-

The Republicrats' Phony Budget War

— The Editors -

The Los Angeles Bus Riders Union

— Scott Miller -

The Consumer Price Index "Reform"

— James Petras -

Britain's "New Labour"

— Harry Brighouse -

Woman-Centered, Activist Agendas

— Deborah L. Billings -

The Remaking of the Congo

— B. Skanthakumar -

The Roots of the Rebellion

— B. Skanthakumar -

Kabila's Friends

— B. Skanthakumar -

Mobutu's Loot and the Congo's Debt

— B. Skanthakumar -

Humanitarian Intervention

— B. Skanthakumar -

The AFDL and Its Program

— B. Skanthakumar -

Mining Congo's Wealth

— B. Skanthakumar -

Pornography, Violence and Women-Hating

— Ann E. Menasche interviews Diana Russell -

The Rebel Girl: Looking at the Gender Grid

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Fables of Bill and the Newt

— R.F. Kampfer - Exploitation and Upsurge

-

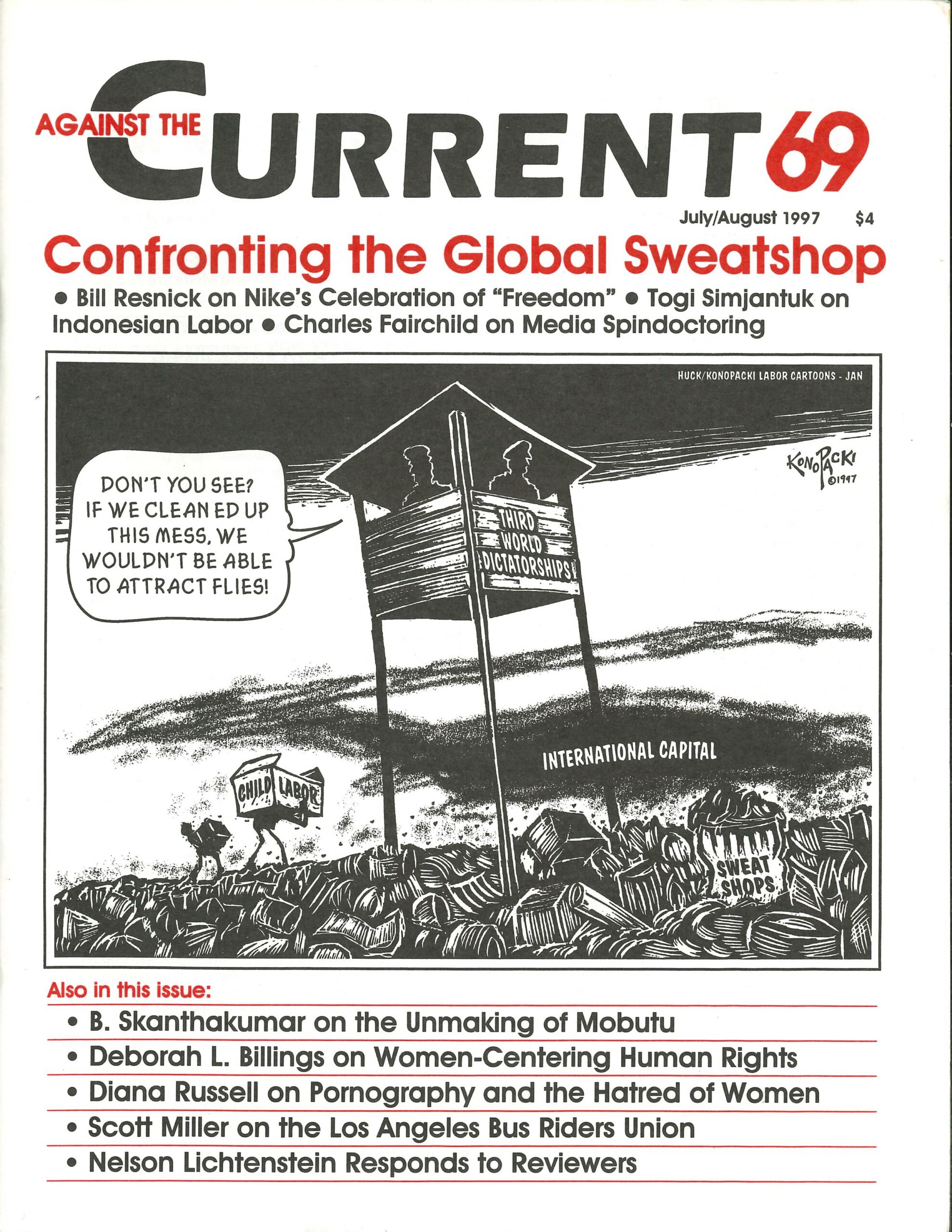

Global Sweatshops' Media Spin Doctors

— Charles Fairchild -

Socialism or Nike

— Bill Resnick -

Indonesia's New Social Upsurge

— Togi Simanjuntak -

Fellow Workers, Fight On!

— interview with Muchtar Pakpahan - Reviews

-

Asian American Incorporation or Insurgency?

— Tim Libretti - Dialogue

-

A Response to Reviewers

— Nelson Lichtenstein - In Memoriam

-

Albert Shanker, Image and Reality

— Marian Swerdlow and Kit Adam Wainer

Catherine Sameh

I OFTEN HAVE the sense that the crudest forms of assigned gender roles have crumbled. That in the late twentieth century United States, the feminist and queer movements have left such indelible marks, there is no turning back. In the age of gender and sexual ambiguity and fluidity, to witness extreme gender stereotypes produces a short of shock. I experienced such a shock in reading about a local beauty pageant.

No, it wasn’t for drag queens, but young girls, many as young as three. My initial assumption was that the article would take a least a somewhat critical look at this obscene ritual. It was a brutal reminder of the power and persistence of gender roles to read otherwise. The reporter for The Oregonian, a woman, opened the article with this passage:

“Lauren Williams, age 3, wears a ruffly pink dress with ruffly pink anklets and white shiny shoes. Her blond hair has been curled. She’s pretty. She’s pink. And she’s sweet. If birthday cakes could walk and talk, Lauren could be one.”

The article goes on to defend beauty pageants, with parents and judges claiming they boost girls’ self-confidence by giving them a singular focus throughout childhood and adolescence. And for girls who might be struggling with the oppressive consequences that challenging gender roles can bring, pageants can be therapeutic. Listen to Melissa Sabin, a 10-year-old:

“I thought of it as a sport,” Melissa says. Asked what she’s learned from participating in pageants, she doesn’t hesitate. “How to be more girlie,” she says. “Last year I only wore jeans and a hat on backwards. Now I think it’s kind of fun to dress up sometimes.”

While it may be true that parents who would condone beauty pageants, or celebrate the ideals of pageant culture, are an anomaly, it’s also true that a nagging, if not growing, panic about gender simmers beneath the surface of everyday life.

As participation in sports for girls increases and tomboy culture is mass marketed, as women — straight and gay — raise sons and daughters alone or with other women, and as many parents take pains to raise strong girls and gentle boys, traditional notions of gender appropriate behavior are taking a beating. As old systems are uprooted, and new ways of thinking, looking and being become possible, anxiety about a future without prescribed gender roles increases, and new penalties for gender transgression are inflicted.

Take the case of Brandon Teena, murdered three years ago in Nebraska for passing as a man. Or Shannon Smith, driven out of the Citadel by constant harassment from her male colleagues. For working-class women and men — or women and men of color who challenge gender roles — their punishments are often greater, as they are perceived to threaten multiple social orders.

More than twenty years after feminists burned symbols of women’s oppression at a Miss America Pageant, I am struck by the curious juncture at which we find ourselves. I walk along the boulevard where I work, and delight in the groups of grunge girls with hats and shirts that read “Girls Kick Ass,” and attitudes to match the slogan. I see strong, athletic bodies of young girls playing soccer in the field across from my house.

Days later, I hear that a local radio station is sponsoring a “chick boat,” a boat full of women to greet the sailors who come to Portland’s yearly Rose Festival. I rage, I sigh, I wonder. I carry on.

ATC 69, July-August 1997