Against the Current, No. 67, March/April 1997

-

Lies, Damn Lies and "Reforms"

— The Editors -

Defying Washington's Embargo

— Phyllis Ponvert -

Behind Peru's Hostage Crisis

— an interview with Coletta Youngers -

Class Struggle in Andalucia

— Loren Goldner -

Another View of the Nicaraguan Election

— Cesar J. Ayala - Chronology of the Revolution

-

Random Shots: The Sexual Is the Political

— R.F. Kampfer -

In Honor of the Left Opposition

— Paul Le Blanc - The Changing Face of Labor

-

John Sweeney's New-Old AFL-CIO

— Jane Slaughter -

Teamster Reformers 2, Old Guard 0

— Henry Phillips - For International Women's Day

-

Arab Women Writers' Problems and Prospects

— Amal Amireh -

The Export of Philippine Women

— Delia D. Aguilar -

Further Dialogue on Pornography

— Nancy Herzig and Rafael Bernabe -

The Rebel Girl: Violence Against Choice

— Catherine Sameh - Reviews

- On Lichtenstein's Biography of Walter Reuther

-

On Walter Reuther: Legends and Lessons

— Michael Goldfield -

Where Studes Lonigan Came From

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Joan Mandell's Tales from Arab Detroit

— Janice J. Terry -

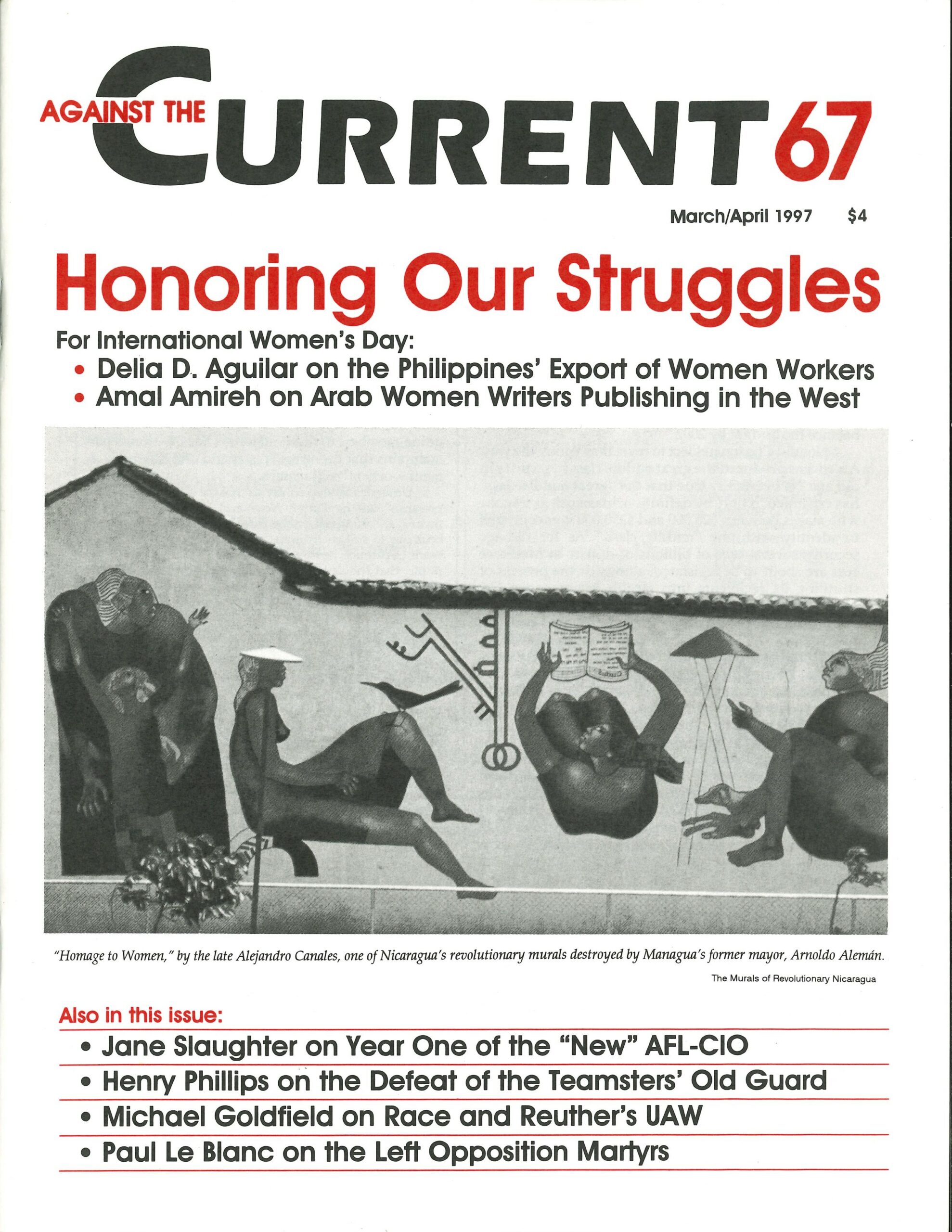

Recovering the Sandinista Murals

— Dianne Feeley -

The Memoirs of Nadezhda Joffe

— Morris Slavin

Patrick M. Quinn

Studs Lonigan’s Neighborhood and the Making of James T. Farrell

by Edgar M. Branch

Arts End Books, Box 162, Newton, MA 02168, 1996,

8.5″ x 11″ sized format, 104 pages, $20 paperback.

JAMES T. FARRELL was the major American novelist most significantly influenced by Trotskyism over a sustained period. To be sure, Saul Bellow was a Trotskyist in his youth, but his engagement with Trotskyism was neither as deep nor prolonged as Farrell’s, which stretched over a decade (1937-47).

In this large format but thin volume, Edgar Branch, the acknowledged dean of Farrell scholars, does a masterful job telling us about the Chicago neighborhood that was the formative crucible for James T. Farrell, his literary alter-egos, Danny O’Neill and Eddie Ryan, and his renowned fictional character, Studs Lonigan.

Located on Chicago’s southside, this thirty-six square block area immediately to the west of Washington Park and bounded by 55th Street (Garfield Boulevard), South Park Avenue (now Martin Luther King Blvd.), 61st Street and Wabash Avenue was home during the teens and twenties for a mosaic of mainly second-generation Americans of European origin–Irish Catholics, Swedish Protestants, Greeks and a sprinkling of Jews.

Farrell and his literary characters were deeply rooted in and anchored by the Irish-Catholic component of the Washington Park neighborhood. Much of Farrell’s prolific fiction is situated in the neighborhood, including, of course, his most well-known and highly regarded work, the Studs Lonigan trilogy (Young Lonigan, The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan and Judgment Day).

Edgar Branch weaves a richly textured description of the neighborhood, tracing its geography, culture and demography. He probes the sociological and pyschological as well as the physical terrain, everywhere linking Farrell’s own experiences and venues with those of his characters. He focuses, like Farrell’s fiction, on the Irish-Catholic community.

The volume is enhanced with fifty-two photographs, some contemporaneous, others taken by Branch himself in 1948, which very nicely illuminate the text. For those interested in Farrell’s youthful formative period and that of Studs Lonigan and his pals, this volume is a gem.

Yet nowhere in the book does Branch mention that Farrell ever became a socialist or was, during the zenith of his literary career, a supporter of Trotskyism. This seems a rather striking omission. One naturally wonders how and why young Jimmy Farrell from Washington Park became a well-known socialist.

Fortunately, Alan Wald in his James T. Farrell: The Revolutionary Socialist Years (New York: New York University Press, 1978) has shown how Farrell had to be extracted from his formative neighborhood before his political development could occur. What liberated Farrell from his parochial origins was his enrollment at the University of Chicago in 1926 (he left in 1929 without taking a degree), the year he and his new wife spent in Paris (1931-32), and his permanent move to New York City in 1932.

There, during the electric thirties–amidst the Great Depression and against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War, the rise of fascism in Europe, and the Moscow Trials–he encountered socialists, communists, and Trotskyists. He was bright, curious, and a constant seeker (throughout his life) of the TRUTH, a predisposition Branch attributes to his Catholic training. Perhaps, but one also clearly shaped and honed in his classes and by his reading at the University of Chicago.

Alan Wald makes it clear that Farrell became a socialist despite his upbringing. Washington Park was not a slum filled with Irish-American lumpen proletarians; rather, it was a solid middle class/working class community that lived in sturdy stone and brick, three-story buildings, each with six spacious apartments.

What is notable, however, is how little conducive it was to any kind of questioning, radical or otherwise, of prevailing societal (i.e. capitalist) values. Indeed, the institutionalized cultural blanket of the Irish-American Catholic Church effectively smothered any such questioning.

James T. Farrell was an anomaly. He escaped. Studs Lonigan did not. (Farrell’s character was based upon his real-life acquaintance “Studs” Cunningham.) Farrell himself noted in his diary in 1933, “I don’t feel that Communism as a philosophy and as a way of life will ever have a great appeal to the educated Catholic, if the latter has been sincerely and deeply Catholic.”

Mike Davis in Prisoners of the American Dream, talking about “why the U.S. working class is different,” generalizes further: “The ingenuity of American Catholicism…was that it functioned as an apparatus for acculturating millions of Catholic immigrants to American liberal-capitalist society while simultaneously carving out its own sphere of sub-cultural hegemony through its (eventually) vast system of parochial schools and Catholic (or Catholic-cum-ethnic) associations.”

One senses that Davis here could be speaking specifically of Washington Park. Perhaps it might not be so much Catholicism as such, but more its peculiar Irish-American variant.

Relatively few Americans of Irish-Catholic ancestry broke their formative molds and became prominent radicals or socialists. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, William Z. Foster, James P. Cannon and the three Dunne brothers of Minneapolis come to mind. But Washington Park clearly was not the same kind of place as those Jewish neighborhoods in Brooklyn or the Bronx that spawned so many thousands of communists, socialists and Trotskyists in the 1920s and ’30s.

Nor was it, for that matter, akin to Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood, just five miles northwest, that produced Saul Bellow and a host of other young Trotskyists clustered around the dynamic and charismatic Natie Gould at Tuley High School.

Edgar Branch, of course, does not pursue these questions. More work is need to analyze the effect that Irish-American Catholic culture and institutions had on stifling radicalism in working-class communities.

Could Studs Lonigan ever have become a socialist? Perhaps. But in a different place and a different time.

ATC 67, March-April 1997