Against the Current, No. 64, September/October 1996

-

Who Gets To Choose?

— The Editors -

Nicaragua: The Mischief of Senator Helms

— Chuck Kaufman and Lisa Zimmerman -

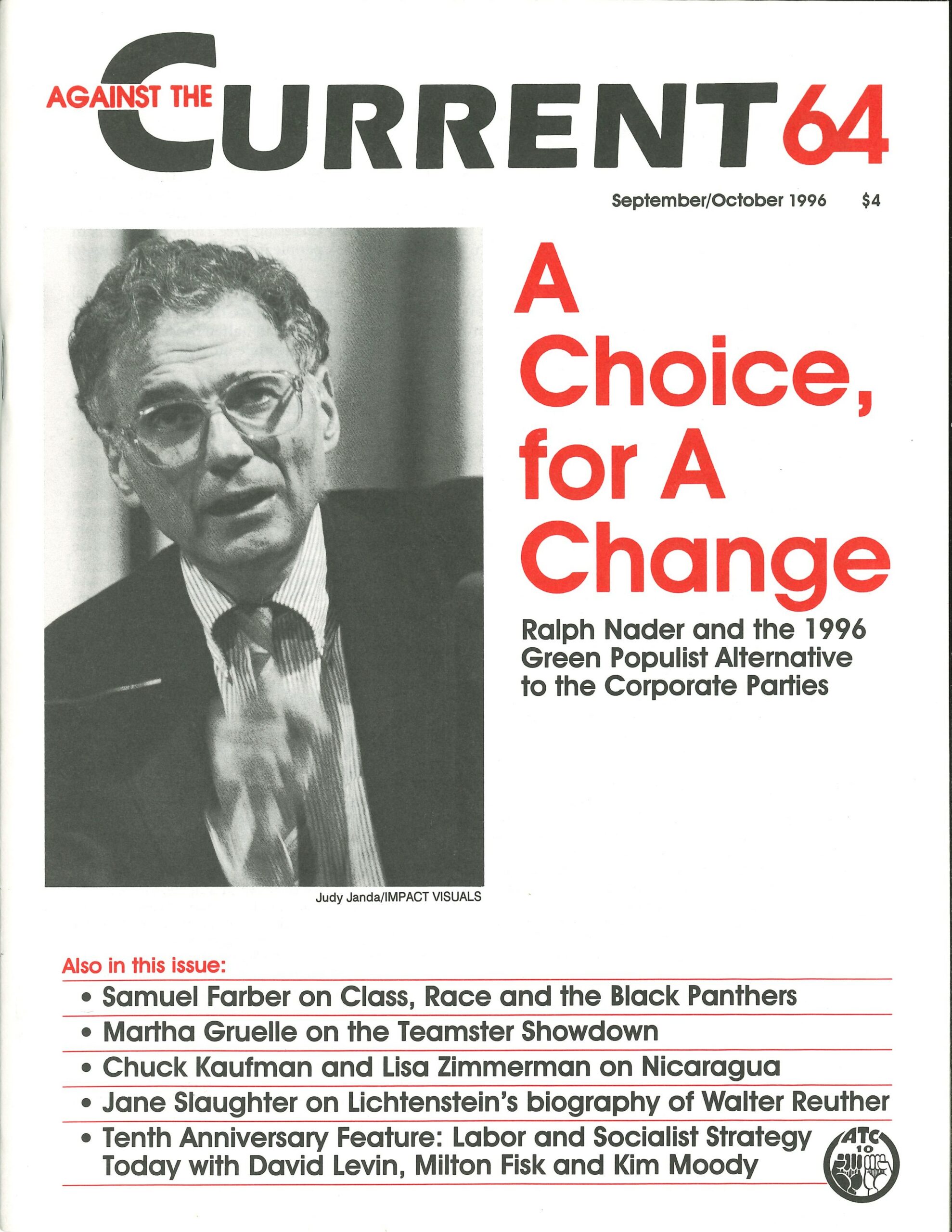

Ralph Nader and the Greens

— Walt Contreras Sheasby -

New Teamsters vs. The Old Guard

— Martha Gruelle -

The End of the Hogan Family Dynasty

— Martha Gruelle -

How Oakland Teachers Fought Back

— Bill Balderston -

The Black Panthers Reconsidered

— Samuel Farber -

The Rebel Girl: Is There Life After Olympics?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Kampfer's Kreative Krossword

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor and Socialist Strategy

-

New York's Latino Workers Center

— David Levin -

Promoting Unity and Solidarity

— Milton Fisk -

Unity Begins Somewhere

— Kim Moody - Reviews

-

The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit

— Jane Slaughter -

A Note on the Mainstream Reviews

— Jane Slaughter -

From Marx to Gramsci: A Reader

— Lisa Frank -

Always Running, Never A Radical

— Christopher Phelps -

Yugoslavia Dismembered

— Kit Adam Wainer -

Building Working-Cass Opposition to Stalin's Dictatorship?

— John Marot -

Evidence from the Archives

— John Marot

Milton Fisk

IN A PERIOD that is frequently called post-industrial, or even post-capitalist, it is refreshing to read Moody’s account, in “ATC” 58, of how important the private industrial sector still is. He points out that the U.S. industrial working class in the private sector, though only 29% of the private productive workforce, generates 44% of the Gross Domestic Product, which is 1.4% more than it generated thirty years ago when it was half the workforce. After establishing the importance of the industrial workforce to the U.S. economy, he goes on to claim that, in view of its importance to the economy, it will have a “central role as `gravedigger’ of the old society and organizer of the new.”

But does his claim about the potential of the private sector industrial working class to become the chief agent in social transformation follow from its economic role? Not only do I think it fails to follow, but also I think that the current situation calls instead for a strategy that emphasizes working-class solidarity among a plurality of working-class organizations. This solidarity must bridge the divide between industrial and other workers, union and non-union workers, white and non-white workers, public and private sector workers, and so on. Giving centrality to industrial workers, as Moody recommends, would make the task of class unity through solidarity a secondary one, one to be realized as spillover from progress in positioning industrial workers for their central role in social change.

A number of developments force us to emphasize working-class unity, a unity that is nonetheless genuinely multi- organizational. They discourage our trying to get unity through making central either some one part of the working class, such as the private industrial working class, or some one aspect of class life, such as the conditions of labor in the labor market and the workplace, which are the chief priorities of the union movement.

The most recent development in this regard has been the turn toward neoliberalism in the economy during the 1980s and 1990s. The other development has been the multiplication among working people over the past quarter of a century of different kinds of organizations-environmental, ending violence against women, civil rights, peace activist, health care reform, low-income housing, workers’ centers . . . . Both developments pose a challenge only to be met by working class unity.

NEOLIBERALISM. The challenge of neoliberalism comes from outside the class. However, the pluralism within the class that arises in response to the multiple forms of oppression and exploitation is a challenge that can be addressed inside a framework of working-class life. After noting why the response to neoliberalism must be unity, I will argue that a unity which is still pluralist makes inappropriate the designation of either one sector or one aspect of working- class life as central.

Neoliberalism has, unlike welfare capitalism, conducted a direct assault on every aspect of working-class life. It doesn’t try to apologize for workplace exploitation with a promise of life-long social security and a promise of even- handedness in labor relations. It attacks the working class at enough places to produce complaints from a variety of groups which have to deal with the injuries of working-class life. It provokes complaints from pensioners, Blacks and Latinos, women on welfare, victims of downsizing, those who depend on public hospitals, and environmentalists.

It is not just the global character of the neoliberal economy that is at work here. There are other aspects of it that, though connected with its global aspect, have direct local effects. Privatization is being used to multiply sources of profit. Labor is being made flexible to cut costs drastically. And banks have grown in importance in respect to nonfinancial enterprises precisely in order to discipline them.

In these circumstances there is an objective basis for unity among those in the working class affected, though in different ways, by the ravages of neoliberalism. Pensioners, women, environmentalists, immigrants, unionists, gays and the unemployed have a basis for wanting their organizations to unite to attack capitalism. For, in its most recent form-neoliberalism-it is sacrificing workers to an unobstructed drive for profits and power.

The subjective basis in consciousness for class unity is, though, lacking. In this regard there are few bright spots in the United States or anywhere else. Among the possible exceptions is Brazil, where the success of the Workers’ Party has been based on bringing together the countryside, the ghetto, and the factory/office. That there is outrage globally is undeniable; that it regularly boils over in social protest is obvious too.

What’s missing, though, is the crucial dialectical ratchetting upward of consciousness in tandem with organization. This mutual reinforcement of consciousness and organization begins to turn mere outrage into the conviction that a capitalism which eats its children not only must but can be slain. This popular conviction would provide class unity with a subjective base, neoliberalism having already provided its objective basis.

NEW ORGANIZATION. To get this subjective basis for working- class unity is the perennial goal of socialists. Are there shortcuts to it through looking for natural detonators of class unity within the class? Moody thinks that the economic centrality of the private industrial working class points to such a shortcut. Its economic centrality gives it, in his view, a leading role in ending the old society and organizing the new.

Moody’s view runs into a series of difficulties. He supposes that industrial workers are distinctive due to their being essential to capitalism. This ignores the fact that in a highly integrated economy other workers also have essential roles. Workers in any number of sectors could bring things to a standstill.

Private sector production workers may generate the surplus from which profits are made. Still, public sector workers are vital to keeping the process of the appropriation of profits going. Clerical workers, by turning off their computers, can stop the flow of official documents needed for business transactions. The agricultural proletariat, by walking out of the fields, could disrupt the reproduction of industrial labor power.

Moody’s back-up argument here is that nonetheless industrial workers create the physical infrastructure-the offices, the roads, the machinery, the jets, the electricity and the ports-for all other economic activity. Finance, trade, and circulation services such as advertising “grow on this productive foundation.”

But by itself physical infrastructure can’t make a contribution to the economy. It must first be harnessed to systems that organize production, to the systems of education, trade and overall governance. And once this has been granted, it will be recognized that the kind of physical infrastructure we have wouldn’t have come about without these systems of organization. So it becomes just as true to say that physical infrastructure grows on these systems of organization. This leaves us without a basis for claiming that industrial workers should have a special role in social change.

The persistent might try to ground the alleged special role in the fact that industrial workers are better organized, or at least have that potential, since they work in larger workplaces for larger corporations.

Moody admits, though, that the unions they are organized into are leading nowhere. Union reform is, in his view, urgent for industrial workers in view of their central role. But then it can’t be because of their being better organized that they have a special role. They’ve been better organized for some time in ways that lead, not toward ending capitalism, but with few heroic exceptions, toward acceptance of its every turn. Of itself, being better organized contains no tendency toward a leading role for industrial workers in ending the old and organizing the new society. There is then no basis for thinking that union reform would give industrial workers a role in that revolution that wouldn’t be shared by other workers in reformed union or non-union organizations.

UNIFICATION. Claims to centrality or primacy are not to be avoided as a matter of principle; I am not a postmodernist who starts throwing things on hearing the words “unity,” “centrality” and “primacy.” Instead I contend that (1) the working class has primacy in the struggle for social change away from capitalism and (2) that tactical primacy can on occasion be assigned to sectors of the working class.

When there is a high level of militancy and organization on the part of some sector of the working class, it will legitimately play a central role in advancing the class struggle at that time. This tactical primacy or centrality is opposed to a strategic one of the sort Moody attributes to the industrial working class. There are now no obvious candidates for tactical centrality in the United States. Even if there were, such candidates would focus on mounting a response to the neoliberal attack on the working class. A key aspect of this response would be the unification of the class.

Making the industrial working class central, as a general strategy for social change, is a mistake from the perspective of forming a class-wide unity. It devalues the potential other sections of the class, or other movements overlapping the industrial working class, have for contributing to creating an organized will to fight against neoliberalism.

The potential of public sector workers, for example, to stand in the way of neoliberalism’s attack on health care as a public good has been amply demonstrated by social security workers in Mexico. The hope that the health care workers in Los Angeles will be able to fight back against the denial of care and privatization is diminished by the absence of a high level of unionism nationally in their sector. But in principle, U.S. health care workers could become tactically central in this period of privatization.

The effort to fragment the working class is successful enough already without making the majority of wage earners think their role is secondary to that of industrial workers. In addition, workers-whether in or outside their workplace-organizing around women’s, environmental, health, housing and security issues are essential to the overall fight. Their struggles threaten neoliberalism’s effort to flexibilize labor when they fight cost cutting and reducing social benefits, and its effort to privatize when they fight deregulation and contracting with private service enterprises.

OUR TASK. Yes, this means not just admitting that industrial workers aren’t central but also admitting that organization outside the union context can be as important as union organization. It is at last to adopt the point of view of the class and resist the imperialism of any fraction of it. It means abandoning all those hoary arguments that try to derive politics from the economics of surplus-value production despite the fact that economics is never more than a framework for politics. It also means abandoning the narrow view that blue-collar outlooks define class consciousness. There are many different outlooks associated with the many different roles of wage earners. One defeats the goal of class unity by setting up one outlook as the norm.

We’ll never get anywhere trying to entice people to join the struggle if they are told they won’t play an equal role. It might have worked with World War II wives to say, “They too serve who wait at home.” But we’re no longer dealing with World War II wives. The class unity we will get, if we get it at all, will be one of shared participation and leadership. Many of the hidden injuries of class will be kept hidden by subordinating the struggles around them to those of only one sector. Instead, we must strive for a multi-organizational unity rather than one with a central administration that subordinates departments.

There have been numerous opportunities in the recent past to work at promoting class unity. The anti-NAFTA movement allowed unionists and environmentalists to have exchanges. The attack on the welfare of single mothers and their children linked the interests of the poor and feminist activists. Workers’ centers have articulated the connections between minority and low-income issues. To develop these connections, the leaderships of different organizations must take risks in reaching out to cooperate, given the persistence of attitudes fragmenting the working class.

Unity and solidarity have to be made explicit goals. Organizations must ask not just how they help satisfy the goals of some sector of the class. They must be sure they also promote solidarity with other working class interests. In addition, they need to project the class into the political sphere where the complex of interests it represents can be pursued independently.

Unless the working class ceases to fold its interests into programs designed to promote capitalism it will remain fragmented. Thus entering the political sphere is a key element in the pursuit of unity. Working to develop independent political parties is not something various working-class organizations can ignore.

REPLIES. One objection to this rejection of Moody’s strategic centrality will be that it is only in a sector like the industrial working class that consciousness is high enough to lead the struggle against neoliberalism and ultimately capitalism itself.

Consciousness migrates from one site to another. It is sometimes higher, for example, among African Americans as an ethnic group than it is among any sector of workers. So the claim about higher consciousness being the privilege of one sector usually reduces to a claim about the potential for higher consciousness. But why should we believe even this weaker claim? I doubt if anyone has shown that being able to stop surplus production at its source can create a more accurate knowledge of the class nature of capitalism than can, say, the gender division of labor under capitalism.

Another objection will be that working-class issues have been too broadly defined here. If the working class is a class that earns its living by wage work, then only the issues of wage work are working-class issues.

This leads us to a fundamental point. Assuming our goal is a class unity structured by solidarity, we couldn’t get to it by defining working-class issues so narrowly. The issues of wage work focus us on the labor market and the workplace. We appeal to justice to solve those issues.

But justice and fairness on these matters go only so far in supporting the satisfaction of others in regard to their other needs. They thus fall short of building unity with solidarity. “It is only when everyone in the class wants everyone else to be able to satisfy each of their needs that we have such a unity”. And that’s why working-class issues need to be all those that affect any segment of the class. Without the solidarity and unity this makes possible, the strength of the bond in the working class would be too weak for it to undertake the struggles it can’t avoid.

The old idea that there is a central working class should be left as a relic of times gone by. Many bought the idea because it seemed right for their times. Whether it was or not, we would pay dearly for trying to keep it when it has ceased to be appropriate. Rather, we should abandon Moody’s idea of a central working class and get on with the important business of building working-class unity.

Milton Fisk teaches philosophy at Indiana University and is a teacher unionist, single-payer health care activist and a member of Solidarity.

ATC 64, September-October 1996