Against the Current, No. 64, September/October 1996

-

Who Gets To Choose?

— The Editors -

Nicaragua: The Mischief of Senator Helms

— Chuck Kaufman and Lisa Zimmerman -

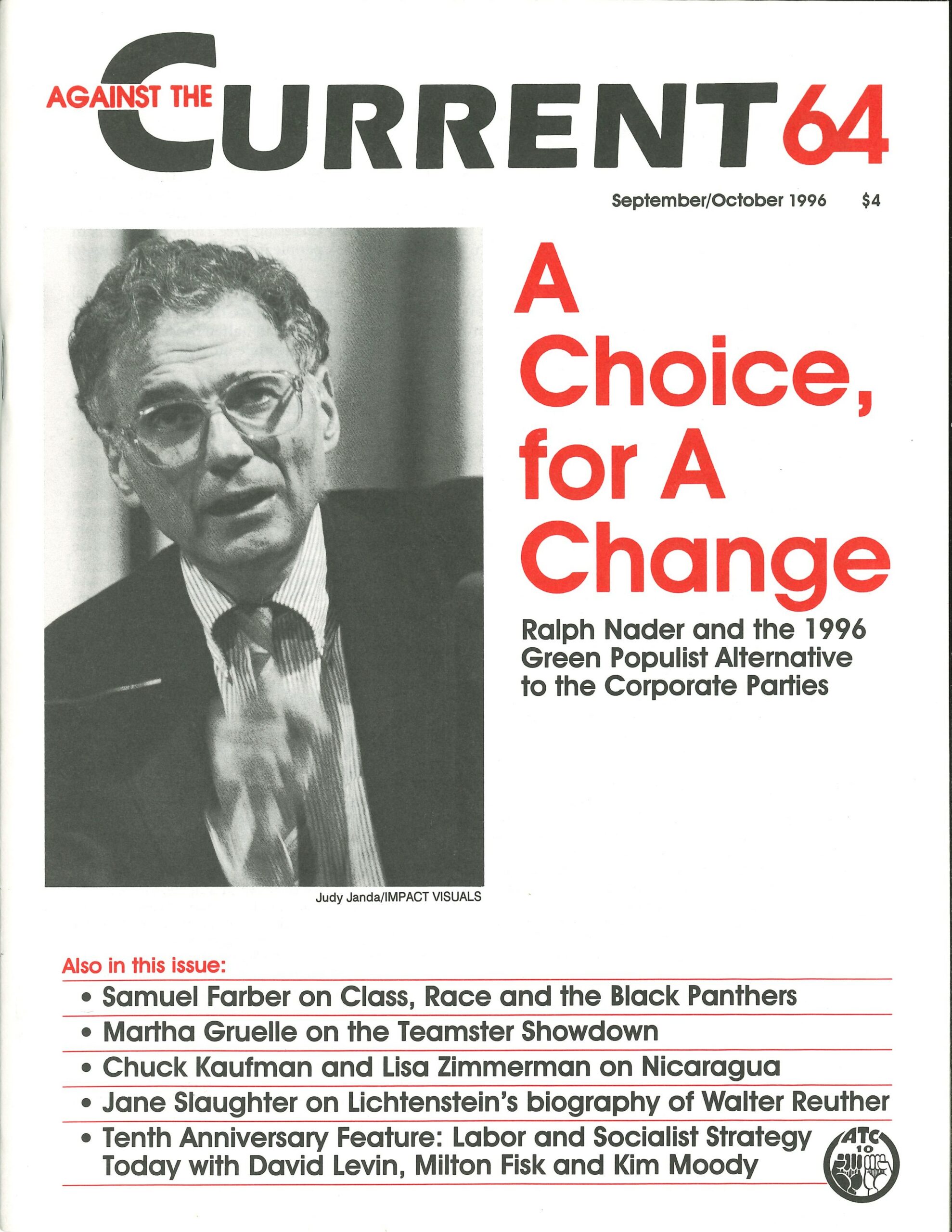

Ralph Nader and the Greens

— Walt Contreras Sheasby -

New Teamsters vs. The Old Guard

— Martha Gruelle -

The End of the Hogan Family Dynasty

— Martha Gruelle -

How Oakland Teachers Fought Back

— Bill Balderston -

The Black Panthers Reconsidered

— Samuel Farber -

The Rebel Girl: Is There Life After Olympics?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Kampfer's Kreative Krossword

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor and Socialist Strategy

-

New York's Latino Workers Center

— David Levin -

Promoting Unity and Solidarity

— Milton Fisk -

Unity Begins Somewhere

— Kim Moody - Reviews

-

The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit

— Jane Slaughter -

A Note on the Mainstream Reviews

— Jane Slaughter -

From Marx to Gramsci: A Reader

— Lisa Frank -

Always Running, Never A Radical

— Christopher Phelps -

Yugoslavia Dismembered

— Kit Adam Wainer -

Building Working-Cass Opposition to Stalin's Dictatorship?

— John Marot -

Evidence from the Archives

— John Marot

Jane Slaughter

The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit:

Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor

By Nelson Lichtenstein

Basic Books, 575 pages, $35.

IN THE LAST paragraph of this biography of Walter Reuther, long-time president of the United Auto Workers, Nelson Lichtenstein maintains that if Reuther were alive today, he would oppose the union’s labor-management partnership schemes, such as the famous love-in at the Saturn factory.

But everything Lichtenstein has written up to that point suggests the opposite: that Reuther not only would have championed labor-management cooperation, he would have convinced himself that it fulfilled his lifelong dream of justice for working people. And he would have been ruthless in crushing anyone in the union who argued otherwise. And he would have made a special point of cozying up to President Clinton, to argue for his latest brainstorm.

Today’s labor movement is puny compared to Reuther’s heyday, and, when they think about it, UAW members wish he were here. (Walter Reuther died in a plane crash in 1970.) Surely the man who helped double auto workers’ wages, who reopened contracts to get more

for workers rather than to give back to the companies, would know what to do.

Reuther doubtless would have had ideas; he was full of them, big ones, grander than any other labor leader of his rank. He jumped into UAW politics in 1936 along with a cadre of other Socialist Party members, “part of that growing class of semi-professional agitators and organizers” radicalized by the Depression. (47)

In 1940, he came up with a scheme for swift conversion of the auto plants to produce “500 Planes a Day.” After the war, he made the presumptuous demand that General Motors freeze car prices–part of his vision of advancing the whole working class, not just UAW members.

He was welcomed as a brother by social democratic heads of state in Europe. In the 1960s, he was way ahead of most white labor leaders on civil rights (although, to be sure, job segregation remained a fact in the auto plants), and he urged “national planning” on LBJ (who was not interested).

But perhaps Reuther’s big vision was one reason he chose the methods he did. Lichtenstein shows that, after the early combative days of the union’s founding, Reuther preferred lobbying those in power (though he seldom prevailed), to mobilizing the rank and file.

In fact, if Reuther estimated that the members’ militancy might get in the way of his reasoned attempts to influence a president, he stifled the former to impress the latter.

During World War II, for example, the government and General Motors demanded that workers give up time-and-a-half pay for overtime, and Reuther agreed. (The union had originally demanded premium pay as a way to discourage overtime and create more jobs.)

In return, Reuther wanted “equality of sacrifice”–a pay ceiling for executives, price controls, and limits on profits. Liberals like Eleanor Roosevelt loved the idea; the union bought $50,000 worth of radio and newspaper ads to sell it. But congressional conservatives torpedoed the corporate share of the sacrifice.

Meanwhile, the UAW ranks were not happy with giving up overtime pay, and Reuther’s rivals in the International Association of Machinists, an AFL union, refused to do so. Workers at a big aircraft plant voted in the Machinists over the UAW. “Can the CIO’s masterminds tell you why they know what’s good for the worker better than he knows himself?” asked an IAM newspaper.

Many AFL unions, writes Lichtenstein, “had never entertained the CIO’s policy-shaping ambitions” (198), and thus were less willing to put aside workers’ interests in favor of the war effort.

Reuther’s response was to demand “equality of sacrifice” from other unions: he asked Roosevelt to issue an executive order banning premium pay for everyone. “Thus,” says Lichtenstein, “was the `equality of sacrifice’ idea reduced from a grand vision to an exercise in administrative theft.” (198)

In these days of the New Democrats, it’s hard to imagine a union leader having the ear of a president. But in 1964, Reuther and LBJ talked on the phone every week; Reuther had high hopes for the War on Poverty and called himself “a devoted member of your working crew” (403).

Therefore, when the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) disputed the seating of the state’s white supremacist delegation at the 1964 Democratic convention, Johnson called on Reuther to beat back the challenge, in the name of “party unity.”

Reuther was then in the midst of contract talks with GM, but he chartered a plane in the middle of the night, rushed to the convention, and started jawboning. He reminded Martin Luther King how much money the UAW had given his organization.

The MFDP was stiff-armed–and, says Lichtenstein, the new generation in the civil rights movement was forever alienated: “Reuther became the symbol of realpolitik, a liberal icon of devious power.” (395) In the name of holding together a big-tent Democratic Party, Reuther contributed to the collapse of the liberal/labor/Black coalition.

How Shop-floor Power Was Lost

Today, the UAW is a thoroughly bureaucratized union that only occasionally uses its power against the automakers. Quite the contrary, the union’s official policy is labor-management cooperation and acquiescence in the “lean” techniques, learned from Toyota, that include speed-up and just-in-time production.

One result: the rate of workplace injuries in auto plants in 1992 was five times that in 1980, and the Big Three blue collar workforce has shrunk by a third. In the factories, full-time “committeemen” represent 300 or so workers apiece–and rake in huge, company-paid salaries.

Scores of “joint” appointees—the workers call them “clipboarders”–have little to do but police the shop floor on behalf of those who appointed them.

It was on Reuther’s watch that GM and the other automakers won the battle against shop floor-level organization. GM was determined not to tolerate working stewards, the organizers of spontaneous, department-level wildcat strikes and resistance to favoritism and speed-up.

The company wanted instead, and got, the legalistic, multi-step grievance procedure, with full-time committeemen negotiating off the shop floor. John Anderson, an old radical who was long retired from GM’s Fleetwood plant when I worked there in 1976, said, “I could only take up a grievance when the foreman told me where it was and who wanted to see me….Our movements were completely controlled.” (143)

Lichtenstein recounts the genesis of this system during the war. UAW locals in GM’s heartland–Flint, Michigan–wanted to strike over the shop steward issue. Reuther, however, feared “that a strike might win the UAW a reputation for careless militancy, thereby jeopardizing his influence in Washington…” (180)

The War Labor Board, which mediated industrial disputes, was a godsend to Reuther. As Lichtenstein tells it, arguing before the board made him feel the equal of GM President Charles Wilson–“pleading their cases like rival lawyers from two big-city firms….The work distanced Reuther from ordinary workers and feisty local union officers, whose interests he now felt to be but one pressure among many…” (181)

The Political Moment that Passed

Lichtenstein recognizes how determined the corporations were to resist any encroachment on their rights, and that government was their handmaiden. Reuther is not held personally responsible for the current abysmal level of working class leverage and left politics.

But Lichtenstein does document that, time and again, Reuther chose not to test his rank and file against the powers that were. The foremost example is his failure to launch a labor party right after World War II.

Labor had emerged from the war with more power than it had ever had–or has had since. It had organized the commanding heights of the industrial economy. Reuther demonstrated his authority to call out his troops in a massive 1946 strike against GM, and all told, three million industrial workers went on strike in 1945-46.

Many of these workers were veterans of industrial battles both before the war and during it (because Reuther’s no-strike pledge was breached repeatedly by the ranks). The social forces were there, but Reuther hesitated.

CIO leaders Philip Murray and Sidney Hillman were staunch Democrats, but many of Reuther’s closest colleagues and advisers were “chomping at the bit” (304) to start a labor party. Lichtenstein raises the possibility that if Reuther had backed Henry Wallace early on, the Progressive Party would not have become simply a creature of the Communists. (Instead he fought tooth and nail against the Progressives.)

In 1948, however, certain that the Republicans would take over the White House, it looked as if the UAW might take the plunge despite Reuther’s doubts. The union’s executive board called for forming a party after the election. Walter’s brother Victor planned an educational conference featuring leaders of the British Labour Party and the Canadian Commonwealth Federation.

But then Truman won the election, and “Reuther consigned all third-party talk to the future.” (306) There it has remained ever since. As Russ Leone, an officer of the big Ford Rouge local outside Detroit, puts it, “You’ll never meet any trade union leader that’ll tell you a labor party is a bad idea. They’ll all say `the time isn’t right.'”

For the rest of his life, Reuther devoted the bulk of his energy to trying unsuccessfully to influence Democratic presidents and lawmakers. He backed Adlai Stevenson despite the candidate’s embrace of the Dixiecrats.

Lichtenstein documents the many backstabs the UAW’s lobbyists received from Democrats in power and out. But any outrage Reuther felt was quickly swallowed because of Reuther’s “growing sense of responsibility for the Democratic Party itself.” (351)

His rebuff of the Mississippi Freedom Democrats was one example, and his behavior on Vietnam another. Despite private doubts about the war, he remained a firm supporter of LBJ and then Humphrey, even when most UAW leaders were backing Robert Kennedy.

Finally, Lichtenstein shows the roots of the current alienation between better-off union members and the working poor. Reuther’s initial vision was to lift the whole working class–at first, through socialism; later in his life, through a corporatist deal among government, labor and business and through a high-productivity economy.

But the auto companies were offering big money for labor peace (it was GM that initiated cost-of-living increases), and soon the union had created a “private welfare state.” (282) There was less incentive to champion national health insurance or full employment when auto workers enjoyed Blue Cross and supplemental unemployment benefits.

By 1968, writes Lichtenstein, “It had been years since Reuther deployed the vocabulary of class conflict. The labor leader’s language was that of liberal humanitarianism or technopolitical bargaining.”

From Militancy to Statesmanship

Reuther was dubbed “the most dangerous man in Detroit” by an auto executive–and for a time he was. He and his comrades did heroic work to bring unionism to the factories. Tactically brilliant, audacious, able to turn stalemates into victories–Reuther’s early ambition served auto workers well.

It is the many years after that time that told the tale, however–when the tasks, if not the enemies, were not so clear. Lichtenstein makes the case that Reuther chose the role of labor statesman over agitator early on.

For the most part, Lichtenstein portrays Reuther as trapped within institutions of his own making. At times, however, he succumbs to the biographer’s temptation to see his subject in the best light.

“Reuther [always] emphasized that a sense of justice and solidarity underlies the union idea,” he concludes–this after telling us ten pages earlier how Reuther put off Black UAW members’ demands for representation and invited the companies to fire Black strikers from the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. (434, 444)

Lichtenstein shows us the origins of some of the union movement’s current weaknesses–little organization at the workplace level, no capacity to act independently in the political sphere, viewed by many non-union workers as a “special interest group.”

The tragedy, today, is that almost no one at the top levels of the labor movement has much of a plan to change this. Bob Wages, president of the feisty Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers, says of his peers on the AFL-CIO Executive Council:

“They are people who are comfortable, people who believe they know how to play this game. They think it’s big stuff to go to the White House and have a handshake, even though on the issues of importance to working men and women, they’re getting screwed royally.”

What’s more, these leaders shun groups such as Teamsters for a Democratic Union that try to take the union back to the job site, or Labor Party Advocates, which held its founding convention in June.

Although elected as an insurgent, the AFL-CIO’s new president John Sweeney has limited himself to a pledge to organize the unorganized–important, but not enough.

Lichtenstein asks, “What would Walter do?” But the answers, if it’s not too late, will come not from union presidents but from the dissidents who even now are organizing against Reuther’s heirs.

ATC 64, September-October 1996