Against the Current, No. 62, May/June 1996

-

Ten Years of Against the Current

— The Editors -

How Labor Loses When it "Wins"

— Peter Downs -

Yale Workers Fight the Power

— Gordon Lafer -

Brazil's Workers Party Redefining Itself

— Michael Shellenberger -

Modern "Gunboat" Diplomacy in the Caribbean

— an interview with Cecilia Green -

"Burn the Haystack!"

— News From Within -

The Clinton-Helms-Burton Travesty

— The ATC Editors -

The IMF Restructures Sri Lanka

— D.A. Jawardana -

Chandrika's "Great Victory"

— Vickramabahu Karunarathne -

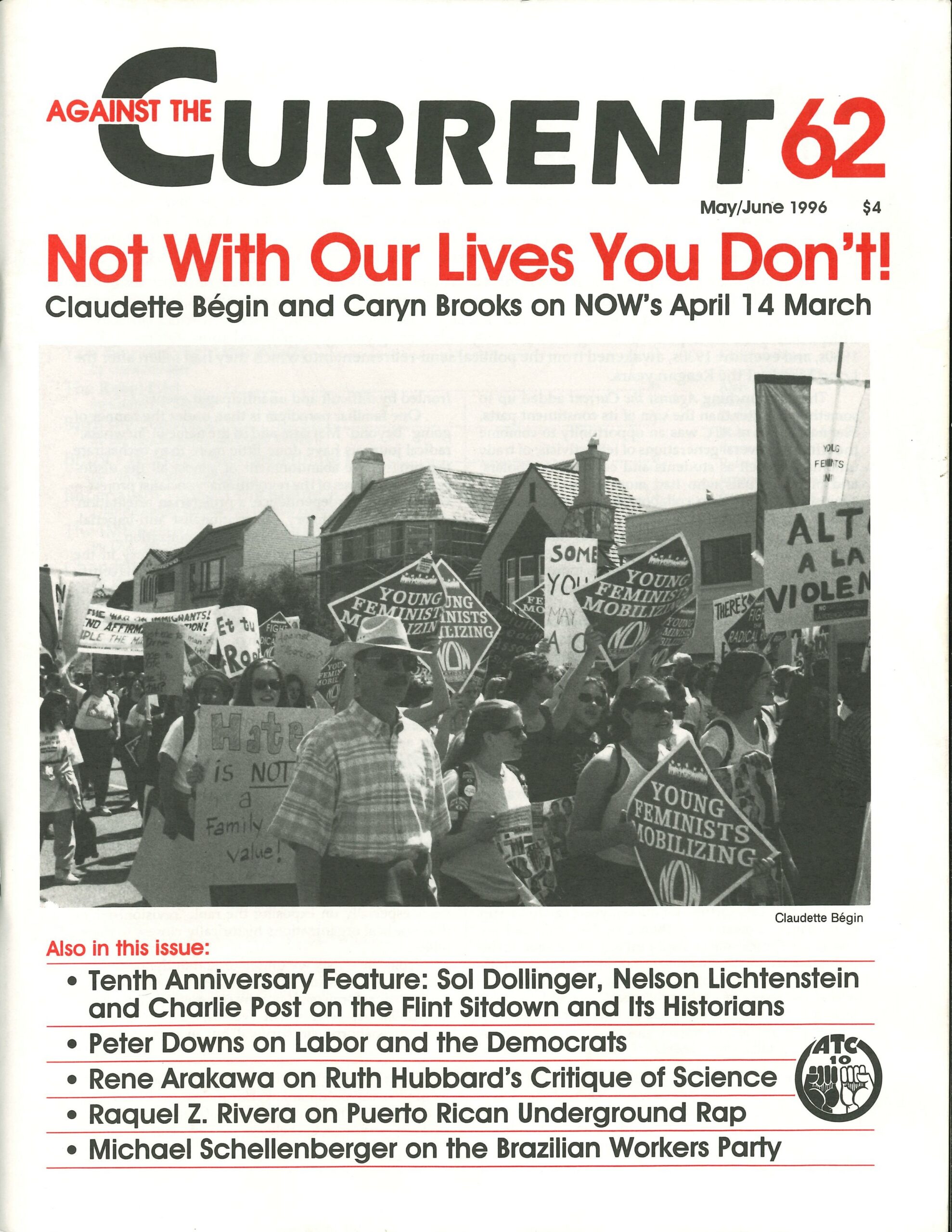

Getting It Right About Now

— Claudette Begin and Caryn Brooks -

Fight the Right

— Claudette Begin -

Ruth Hubbard's Feminist Critique of Science

— Rene L. Arakawa -

Reclaiming Utopia: The Legacy of Ernst Bloch

— Tim Dayton -

Policing Morality: Underground Rap in Puerto Rico

— Raquel Z. Rivera -

Answering Camille Paglia

— Nora Ruth Roberts -

On Being Ten

— Greetings from Our Friends -

Letters to the Editors

— Peter Drucker; Linda Gordon - The Great Flint Sitdown: An ATC 10th Anniversary Feature

-

Introduction: The Flint Sitdown for Beginners

— Charlie Post -

The Rebel Girl: The Real Threat to Life

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Politics, Religion and Mad Cows

— R.F. Kampfer -

Flint and the Rewriting of History

— Sol Dollinger -

Politics and Memory in the Flint Sitdown Strikes

— Nelson Lichtenstein - Reviews

-

McNamara's Vietnam

— Lillian S. Robinson -

Ken Saro-Wiwa's Antiwar Masterpiece

— Dianne Feeley -

Statement to the Court

— Ken Saro-Wiwa - In Memoriam

-

Marxist Art Historian: Meyer Schapiro, 1904-1996

— Alan Wallach

Raquel Z. Rivera

Your nuts I will crack and

to hell I’ll send you back

–Alma, PLAYERO #38 (1994)

Spit in her face

Piss on her cunt

‘Cause that fucking bitch Is not

worth much(1)

–Las Guanabanas Podrias, The Noise #2 (1994)

IN FEBRUARY 1995, the Drugs and Vice Control Bureau of the Police Department of Puerto Rico raided six record stores in the San Juan area. Hundreds of cassettes and compact disks of underground hip-hop music were confiscated. These recordings were said by the police to violate local obscenity laws through their crude references to sex and their incitement to violence and drug use. The high-profile raids brought underground music to the forefront of public discourse and triggered a fierce debate regarding morality, censorship and artistic freedom.

Underground music has been a vital part of the island hip-hop culture since the early 1980s. The term “underground” was originally used to differentiate mainstream rap music from the type of rap produced and distributed in the informal economy. Currently, “underground” is a more elusive term, since it has also come to describe music that is faithful to what D.J. Playero calls the “underground ghetto aesthetic,” even if it has had formal commercial success.

Underground has been a popularized music, albeit outside the scope of the mainstream media, for more than a decade. However, it began catching the mainstream public’s eye in 1994, when underground recordings began to circulate within the formal economy. Wiso G.’s Sin Parar (1994) was the first underground recording to be produced by a major record label and sold in stores. Later in the year, Playero’s #38, already made enormously popular through informal channels, made its appearance in stores and became one of the biggest selling underground productions.

Whereas commercial rap had been tailored to fit media requirements regarding language and themes, underground rap, until the release of Wiso G.’s Sin Parar, developed and thrived with a great measure of independence from media policing and censorship. Thus, underground had not been forced to rid itself of language considered to be too crude, vulgar or violent for mass media exposure. While the language of mainstream rappers was closely monitored, underground artists prided themselves on being faithful to their everyday language.

The increasing popularity, visibility and mass availability of underground eventually began generating concern regarding the possible effects of this music on its largely youthful audience. Media time and space was monopolized by people who approved of state censorship on moral grounds.

Underground was obscene, thus immoral, thus dangerous, thus it should be censored. It was that simple. Underground was seen as filth and degeneration posing as art. The music’s frequent crude references to sex, violence and marihuana were perceived as an element of incitement for young people to model their behavior after the lyrics. Underground was portrayed as a cultural expression attempting against the fiber of morality and decency upon which social order rests.

All Shook Up

The mainstream media “discovery” of underground and its irreverent lyrics came as a great shock and created a sense of national alarm. Various TV and radio shows took up the topic of underground and censorship. It was underground open season.

A few days before the raids, Carmen Teresa Figueroa moderated a TV special which promised to “uncover the ‘secrets’ of underground.” The show was aimed at parents who wanted to know how this “noxious” music was affecting their children.

Several days later, TV show host Luis Francisco Ojeda joined the underground bashing crusade. His star guest was Waldemar Quiles, president of the House of Representative’s Commission on Education and Culture. The legislator expressed that his objective was to amend the Penal Code in order to typify the production of underground rap as a serious crime. In both TV shows, the “noxious” character of underground was treated as a proven fact.

Yolanda Rosaly, media critic for El Nueva Dia, the most prestigious and powerful island daily, wrote an impassioned column five days after the raids alerting parents against the dangers of this “underworld” music. Rosaly’s word choices are quite telling of the classist hysteria fueling the attack on underground. She deemed underground to be equivalent to the music of a sinister “underworld”, i.e. the criminal underworld of the poor and young. For her, the lyrics are “simply horrendous and revolting” and reflect the perverse attitudes and beliefs of criminals; therefore, the Police Department acted in the defense of social order and the public well-being by censoring them.

Luis Antonio, radio host for Wapa Noti-Radio, in a program aired on February 17, 1995 commended the Puerto Rican Chief of Police for opposing this “type of pornographic expression […] that clearly constitutes an incitement to violence and pornography.” Wavering between his “objective” role as show host and angrily denouncing the abominable pornographic contents of underground, Luis Antonio set the tone of the program as a pro censorship rallying cry. Thus, it came as no surprise that most callers held positions like the following.

Good afternoon. I’m calling from Rio Piedras. I’m glad that people are talking about this and are against it because as a parent or grandparent one has to be very concerned about this. I think that just like there are laws that say you can’t use obscene language anywhere, there has to be a law that restricts this. These kids that blast this music have to be stopped before the younger kids start listening to it as well. This situation is truly alarming.(2)

The fact that media time was monopolized by pro-censorship views does in no way mean that there were no voices being raised against state censorship. Dissenting voices were still heard over the airwaves. The token rappers present in radio and TV shows argued strongly against censorship and the myths being propagated about underground.

“Rumbo Alterno,” a radio show hosted by Hiram Guadalupe and which had an all anti-censorship guest panel, aired in March 1995. But programs like “Rumbo Alterno” were, unfortunately, the exception.

The Front for the Defense for Democratic Rights was a group that organized around the same time that the raids took place and took a firm anti-censorship stance. The Front staged demonstrations and put out press releases voicing its concern that “under the cloak of morality, [the Police Department] is constantly taking more steps that violate the democratic rights of assembly and free speech. The group held that the Police and its Anti Vice Squad were serving the interests of conservative groups like Morality in Media who want to impose their concept of morality on everyone else.

Several newspaper articles which questioned state censorship were printed. Among these were “Rappers rap bum rap and hypocrisy” by Jorge Luis Medina and “Killing the messengers?” by John Marino, which appeared in The San Juan Star. “Underground: Aobscenidad o realidad?” written by Pedro T. Berrios Lara and published by the University of Puerto Rico student newspaper La Iupi was another article which took an anti-censorship stance.

Dialogo, the official newspaper of the University of Puerto Rico, saw a lively debate on underground erupt in its pages. Three of the articles written expressed strong anti-censorship views. One was written by Carmen Oquendo and I, the other by Jose Luis Ramos Escobar, and the other by Carmen Oquendo and Lilliana Ramos.

The charges brought against the commercial establishments that sold underground were eventually dismissed by the Superior Court of San Juan. This court decision was met by Police Chief Pedro Toledo vowing to fight against what he deemed a pornographic expression which endangers the quality of life of Puerto Ricans.

We will investigate where it was that we failed. We will continue our struggle… if the courts want to permit the sale of this type of pornographic material, we have to figure out a way to fight this evil. (El Nuevo Dia, 2/17/95, 23)

The court decision was greeted with relief by all of us who treasure tolerance and artistic freedom. However, the paranoia unleashed by the state’s dramatic censorship actions could not be overturned by court order. The misconceptions and prejudices surrounding underground lingered on.

Reality and Representation: No Es Lo Mismo Ni Se Escribe Igual

The primary accusation directed towards underground is that it has a dangerous influence on youth. For censorship advocates like Reverend Milton Picon, Yolanda Rosaly and Police Chief Pedro Toledo, the alleged fact constitutes sufficient grounds for censoring this music. In contrast, for more moderate critics like Jose Luis Ramos Escobar, a professor of Theater Arts at the University of Puerto Rico, nothing productive is accomplished by censorship. Still, conservative and moderate critics agree that underground has indisputable harmful effects on children.

A frequently unchallenged assumption shared by the pro-censorship as well as the anti-censorship positions is thus the question of meaning and effect, or representation and consumption. Much of the moral panic ensuing from the disclosure and “decoding” of underground lyrics was based on the assumption of a simplistic connection between lived relations and artistic representation.

Art and reality are conflated when most critics refuse to acknowledge that there might be a distance between rappers and their texts. The difference between art and reality is also ignored when audiences are assumed to consume passively and mimic obediently. Ramos Escobar states in an article in Dialogo that

there is no doubt that underground is an element of incitement and stimulus to certain types of conduct that frequently threaten human dignity and the common good, defined in communal and not institutional terms.

Underground music is accused of promoting and inciting certain types of behavior. However, it is difficult, if not impossible, to assess effect. Two U.S. Legislative Commissions on Pornography and dozens of scientific research teams have not been able to settle the issue of how violent art influences reality. So even though Ramos Escobar and countless others claim that common sense is proof enough that there is a direct correlation between artistic representation and action, there is no conclusive scientific evidence to support this.

Carmen Oquendo and Lilliana Ramos, in the following month’s Dialogo, questioned Ramos Escobar’s assumption that underground lures children into depraved behavior. For Oquendo and Ramos

it is innocent to think of a neat causal relationship between rap and violence without scientifically examining how much teen violence stems from rap and how much from violent homes and divorces, parents’ alcohol abuse, incest, neglect and abandonment.

A month later, Pedro Sandin Fremaint joined the debate in Dialogo by jumping to Ramos Escobar’s aid. In his haste, Sandin misinterpreted Oquendo and Ramos’ argument to mean that music has no bearing whatsoever on children’s behavior. He snidely remarked that he dared guess that Oquendo and Ramos don’t have children because “otherwise they would know that children don’t hibernate while scientists reach their conclusions.” His wisecrack was amusing, as well as paternalistic and senseless.

Sandin seems to believe that only parents have valid opinions on this matter; he also assumes that all parents will agree with his own and Ramos Escobar’s causal arguments.

Sandin missed Oquendo and Ramos’ point. The latter are not saying that there is no connection whatsoever between art and reality, but rather, that there is no definitive proof of causality. Music is one of the many factors that may influence children’s behavior.

The act of art consumption is not uniform across individuals, groups or contexts. Theorists like Stuart Hall and Michel de Certau assert that consumption is such a complex process that it should be considered another act of production.(3) In order to understand consumption, the possibility of multiple interpretations needs to be taken into account. I agree.

Some people who take the Bible as their spiritual guide (like Anabellie, my younger sister) are respectful and tolerant people, others (like Reverend Milton Picon) are intolerant, rabid homophobes. Similarly, some people who read the Bible are sex offenders; other sex offenders prefer porno magazines. The Bible and porno magazines are texts. The impact that they might have on people’s beliefs and actions varies widely. They cannot be said to “make” anybody do anything.

Jack Thompson, an anti-porn activist from Florida who during 1990 fervently advocated the censorship of rap group 2 Live Crew’s album, would disagree with me. Thompson asserted the following in a TV show aired at the time when the debate over 2 Live Crew was raging:

The evidence is overwhelming […] that this material, which combines sex, not just dirty words but sexual acts graphically described with violent acts, and encourages violent acts against women, actually causes some people to act out those violent sexual acts. […] There are eight-year old children who have had to have psychiatric counseling because of the contents of 2 Live Crew’s [album].(4)

For Thompson, the cases of “some people” who have allegedly enacted violent lyrics constitutes proof that music can be harmful. Any crime committed “under the influence” of music thus makes the it intrinsically detrimental.

Jello Biafra, former guitarist of the punk band Dead Kennedys, challenged Thompson’s argument: If 2 Live Crew’s album can be pronounced harmful because eight-year olds have allegedly needed psychiatric treatment after listening to it, then the Bible should also be proclaimed harmful since numerous heinous crimes have been committed in its name.

Underground lyrics frequently glamorize violence and sexism. Violence and sexism are also sensationalized in other musical genres, soap operas, the news, movies and in our day to day relations. Underground, however, is thought to influence youth behavior more than other genres since the identity of young people is often tightly related to the music they like.

Professor Ramos Escobar says to have “performed a short investigation among several of my 14-year-old son’s friends […] and they recognized that they had altered their conduct according to what the songs say and the expectations of their peers.” Thus, concludes Ramos Escobar, the music induces the audience to change their behavior.

I have the feeling that if these boys have in fact become more violent or sexist since they began listening to underground it has more to do with “the expectations of their peers”, among other things, than merely with what the songs say. Although I disagree with him, it would be wonderful if Ramos Escobar’s allegations were in fact true.

If misogynist underground music makes boys more misogynist, then the solution should be easy: Strap the boys in place and make them listen to feminist rappers for several weeks straight. Ivy Queen and Jackie might instill in them some feminist common sense. For the hard core cases, however, I recommend New York’s Bytches With Problems. If art did indeed equal reality, there would probably be nothing better than the Bytches’ murderous revenge fantasies to stop a sexist puppy dead in his tracks.

The Aesthetics of Violence or “Baby, I Like It Raw”

Media time and space has been dominated by the portrayal of underground rappers as (at worst) dangerous criminals and (at best) deluded and alienated youngsters. Underground art has also been understood and explained as a mere reflection of a monstrous underground truth; underground artists are the dark angels spinning the factual tales of their own perdition. The ludic and playful aspect of underground has been ignored, so that lyrical fantasies are taken to be true accounts of the rappers’ personal lives.

Underground songs do not merely reflect reality or express rappers’ innermost feelings. Underground artists do weave and sell crude tales of the urban reality. But underground rappers are also in the business of elaborating and selling fantasies. They also make money by rapping outrageous songs whose sole intent is to shock and offend. And why rap about things that go against most people’s sense of order and decency? Simple. “Es por joder,” rapper Frankie Boy says. It’s fun and it sells.

Contrary to the stereotypical and simplistic perceptions that dominate the public imagination, underground artists come in various shapes and sizes; they engage in equally varied intellectual and poetic approaches. Confining these rappers to the “from criminal to alienated youth” range is ignoring the richness, variety and complexity of underground. The assumption that underground audiences mindlessly model their behavior after the lyrics is equally presumptuous.

Most critics of underground have not only been ill informed, but have approached underground with great arrogance (not to mention contempt). They claim to have performed the ultimate decoding of the underground lingo, since these young, poorly-educated savages are presumed to be unable to speak for themselves. They have attempted to study underground by leaping the poetic and generational gap that separates the underground “them” from the mainstream “us.” Most have landed flat on their butts.

Unlike many of the media critics, underground artists and their audiences have a sense of humor and know how to differentiate between art and reality. That is perhaps why rappers haven’t gone after their censors with A.K.s or Glock nines.

Notes

- The translation is mine.

back to text - The translation is mine.

back to text - Michel de Certau, The Practice of Everyday Life, (Berkeley: California Press, 1984); Stuart Hall, “Encoding, Decoding,” 90-103 in The Cultural Studies Reader, edited by Simon During (New York: Routledge, 1993).

back to text - Adam Sexton, Rap on Rap: Straight-Up Talk on Hip-Hop Culture, (New York: Delta, 1995): 154.

back to text

ATC 62, May-June 1996