Against the Current, No. 62, May/June 1996

-

Ten Years of Against the Current

— The Editors -

How Labor Loses When it "Wins"

— Peter Downs -

Yale Workers Fight the Power

— Gordon Lafer -

Brazil's Workers Party Redefining Itself

— Michael Shellenberger -

Modern "Gunboat" Diplomacy in the Caribbean

— an interview with Cecilia Green -

"Burn the Haystack!"

— News From Within -

The Clinton-Helms-Burton Travesty

— The ATC Editors -

The IMF Restructures Sri Lanka

— D.A. Jawardana -

Chandrika's "Great Victory"

— Vickramabahu Karunarathne -

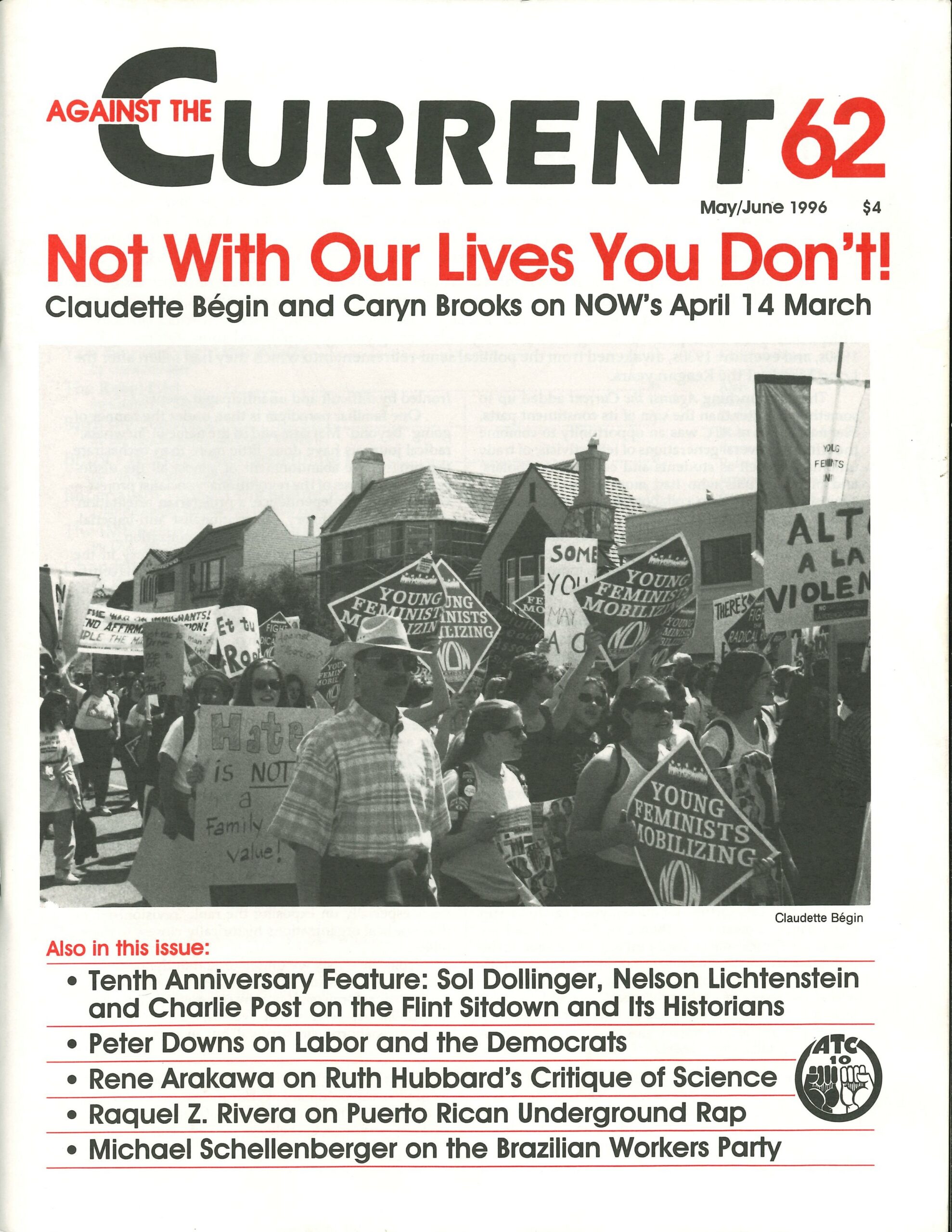

Getting It Right About Now

— Claudette Begin and Caryn Brooks -

Fight the Right

— Claudette Begin -

Ruth Hubbard's Feminist Critique of Science

— Rene L. Arakawa -

Reclaiming Utopia: The Legacy of Ernst Bloch

— Tim Dayton -

Policing Morality: Underground Rap in Puerto Rico

— Raquel Z. Rivera -

Answering Camille Paglia

— Nora Ruth Roberts -

On Being Ten

— Greetings from Our Friends -

Letters to the Editors

— Peter Drucker; Linda Gordon - The Great Flint Sitdown: An ATC 10th Anniversary Feature

-

Introduction: The Flint Sitdown for Beginners

— Charlie Post -

The Rebel Girl: The Real Threat to Life

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Politics, Religion and Mad Cows

— R.F. Kampfer -

Flint and the Rewriting of History

— Sol Dollinger -

Politics and Memory in the Flint Sitdown Strikes

— Nelson Lichtenstein - Reviews

-

McNamara's Vietnam

— Lillian S. Robinson -

Ken Saro-Wiwa's Antiwar Masterpiece

— Dianne Feeley -

Statement to the Court

— Ken Saro-Wiwa - In Memoriam

-

Marxist Art Historian: Meyer Schapiro, 1904-1996

— Alan Wallach

Dianne Feeley

Sozaboy, a novel in rotten English

Longman Publishing Company, 10 Bank Street,

White Plains, NY 10601-1951). $10.95 paperback.

SINCE THE SANI Abacha military regime seized power in 1990, the Ogoni tribe, an ethnic minority living on the Niger delta in southeastern Nigeria, has suffered extremely brutal repression. Amnesty International points to government-instigated attacks resulting in at least 100 extrajudicial executions, 600 Ogoni detained, and the destruction of dozens of villages.

On November 2, 1995 a kangaroo court convicted nine key Ogoni leaders of inciting to murder. Defying international human rights concerns, the regime carried out the executions on November 10th.

Ken Saro-Wiwa was the most prominent of those executed. He was the author and producer of probably Africa’s most popular TV series, “Basi & Co.” Running in the mid-eighties for more than 150 episodes, the soap opera had upwards of 30 million viewers.

Saro-Wiwa was also the author of at least seven books, including novels, plays, poems, an autobiography (On a Darkling Plain) and children’s books. His 1992 manifesto, Genocide in Nigeria: the Ogoni Tragedy, outlined the exploitation and pauperization of the Ogoni people by both the Nigerian government and Shell Petroleum Development Company.

Instrumental in setting up the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (Mosop), he helped it to carry out effective and nonviolent mass protests and became its chief spokesperson.

Ten years ago this extraordinary man wrote a brilliant antiwar novel, which is now available in Longman’s African Writers series.

During the Nigerian civil war (1967-70) — when one million people died, mostly from starvation and disease — Saro-Wiwa worked as a civilian administrator in Bonny, a crucial oil port on the Niger River delta. At the war’s outbreak he fled from the new Biafran state.

Saro-Wiwa did not identify with the aspirations of General Ojukwu, who was from the area’s dominant tribe — the Ibo. For Saro-Wiwa, then, the rhetoric of self-determination was hollow. As he has pointed out in several of his essays, colonialism isn’t simply European, but has been long practiced in Africa by dominant tribes against smaller tribes.

Trouble and Chaos

In Sozaboy the Biafran government’s representatives are absent. Instead, their orders are carried out through the tribe’s chief, who organizes the special war tax and makes sure to get his cut. In other places, lower-level army officers do the job. Throughout Saro-Wiwa is merciless in his portraits of those who operate on behalf of the state: they are corrupt and brutal.

From the novel’s first sentence — “Although, everybody in Dukana was happy at first” — the direction is downhill, in the trouble’s direction. Given the unrealistic expectation of overcoming the corruption of the previous regime, hope quickly recedes. In its places comes even greater corruption, followed by fear and the prediction that the world will end.

Mene, the novel’s everyman, worries about whether he will ever be able to have a life — meaning marriage, a job, a family. And so he naively chooses to become a soldier, consequently losing everything with the first roll of the dice.

Mene is totally naive, and remains so until the final page of the novel. The reader sees from the prism of Mene’s vantage point, but always knows more than he does. Yet despite his limited knowledge, Mene always manages to land on his feet while the others — who started out with him — quickly die.

Mene is the anti-hero, who sets off on a long journey, manages to survive against incredible odds, yet returns only to find his village destroyed, his mother and wife dead. He is perceived by his fellow villagers to be a ghost whom they must kill in order to survive. He has survived, but to what purpose? There is no place for him.

In contrast to the novel’s main character is the tall man who appears throughout the novel as Mene’s chief tormentor. We meet him first in the African Upwine Bar. If Mene is everyman, the tall man is fate. As he explains, there is “trouble.” And trouble means fighting and dying.

His companion asks him to judge the situation, but the tall man refuses:

Well, I don’t think it is good thing or bad thing. Even sef I don’t want to think. What they talk, we must do. Myself, if they say fight, I fight. If they say no fight, I cannot fight. Finish. (17)

Mene encounters the tall man several times in the course of his life as a soldier. The tall man is the enemy soldier, the nurse, the traitor and prison guard all rolled into one. The tall man saves him, only to become his savage prison guard at another stage. Finally the tall man is ordered to kill all the deserters — only to discover he has run out of bullets.

As with so many other troubles Mene has, pondering the reality of the tall man proves to be a difficult task:

And now this Manmuswak is again with our own sozas and no longer with enemy sozas. Or abi na which side the man dey now? At first I could not believe my eyes because I cannot understand how this Manmuswak can be fighting on two side of the same war. Is it possible? Or is it his brother? Or are my eyes deceiving me because I am sick since a long time? Or is it ghost I am seeing? (166)

First Mene believes the tall man is an apparition, but when he doesn’t fire, Mene opens his eyes, sizes up the situation — and escapes his fate.

It is only in the last page of the novel that Mene grapples with what he has learned. It is the knowledge of his own survival that forces him to extract a lesson. Cast out of his own village, he meditates on the death of his wife and his mother:

Quote And as I was going, I was just thinking how the war have spoiled my town Dukana, uselessed many people, killed many others, killed my mama and my wife, Agnes, my beautiful young wife with J.J.C. [Johnny Just Come — i.e. pointed breasts] and now it have made me like porson wey get leprosy because I have no town again.

Double quote And I was thinking how I was prouding before to go to soza and call myself Sozaboy. But now if anybody say anything about war or even fight, I will just run and run and run and run and run. Believe me yours sincerely. (181)

The deep cynicism that pervades the novel becomes explicit. There are no ideas worth fighting for, all is simply the superficial and silly view that being a soldier is somehow noble.

This view stands in sharp contrast to the writing of Ken Saro-wiwa’s fellow countryman Chinua Achebe, who finds the ideology of the Biafran secessionist vision still a noble cause that has been compromised by corruption. Achebe, an Ibo, was a spokesperson for the Bifran side. (See his story, “Girls at War.”)

Saro-Wiwa gave a subtitle to his novel, “a novel in rotten English.” His antiwar novel, then, is experimental in its sustained use of pidgin English. Other authors, notably Achebe, have used such English in their dialogue, but Sara-Wiwa has constructed its language in order to reflect the reality.

In fact, the novel ends as if it were a letter Mene had written home to his family, thus the novel is a kind of monologue Mene — not the author! — has composed.

In his preface to the novel, Ken Saro-Wiwa explains:

Sozaboy’s language is what I call ‘rotten English,’ a mixture of Nigerian pidgin English, broken English and occasional flashes of good, even idiomatic English. This language is disordered and disorderly. Born of a mediocre education and severely limited opportunities, it borrows words, patterns and images freely from the mother-tongue and finds expression in a very limited English vocabulary. To its speakers, it has the advantage of having no rules and no syntax. It thrives on lawlessness, and is part of the dislocated and discordant society in which Sozaboy must live, move and have not his being.

Above all, Saro-Wiwa reflects the chaos and lawlessness of the war by introducing the chaos and lawlessness of the language. Of course it only appears to be chaotic. But it creates an idiomatic rhythm that both functions to provide comic relief and the power of a distinctive voice.

Yet it is only at the novel’s end that one realizes the whole story is like a letter read aloud. The glossary in the back lets the reader not only look up the unfamiliar expressions, but gives evidence to the writer’s control over the chaos.

ATC 62, May-June 1996

Interesting he saw self-determination as hollow. Now his people are declaring independence. The interests of the Niger Delta people has always been better served by the Igbo but they do not realize this. The same Petroleum Institute that Nigeria has planned to move up north was planned by Ojukwu to be sited at Port Harcourt. Whatever ‘colonization’ the people of the South South fear by Igbo is really unfounded. We have always had similar interests but the petty jealousies get in the way. The Igbo are not hated for killing Niger Deltans or trying to convert them to their religion but because they compete for jobs and have successful businesses where they go. This would continue to keep the Niger Deltans down.

As for the Igbo, we can hold our own with or without the support of any region. We do not need their oil or anything they have. Whether the Niger Deltans choose to remain in Nigeria or join Biafra, we will sour to they skies. Biafra is God’s will and it shall b done.