Against the Current, No. 58, September/October 1995

-

Save Mumia Abu-Jamal

— The Editors -

The Right's New Dynamism

— Christopher Phelps -

The Pseudo-Science: Creationism

— Christopher Phelps -

The Gulf War Syndrome Mystery

— Pauline Furth, M.D. -

Britain: Conservatives Collapse & Labor Lurches Right

— Harry Brighouse -

Can Bosnia Resist?

— Attila Hoare -

Radical Rhythms: "Dancing on John Wayne's Head"

— John Greenbaum -

Rebel Girl: Murder, the Double Standard

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Kampfer, Eat Like Him

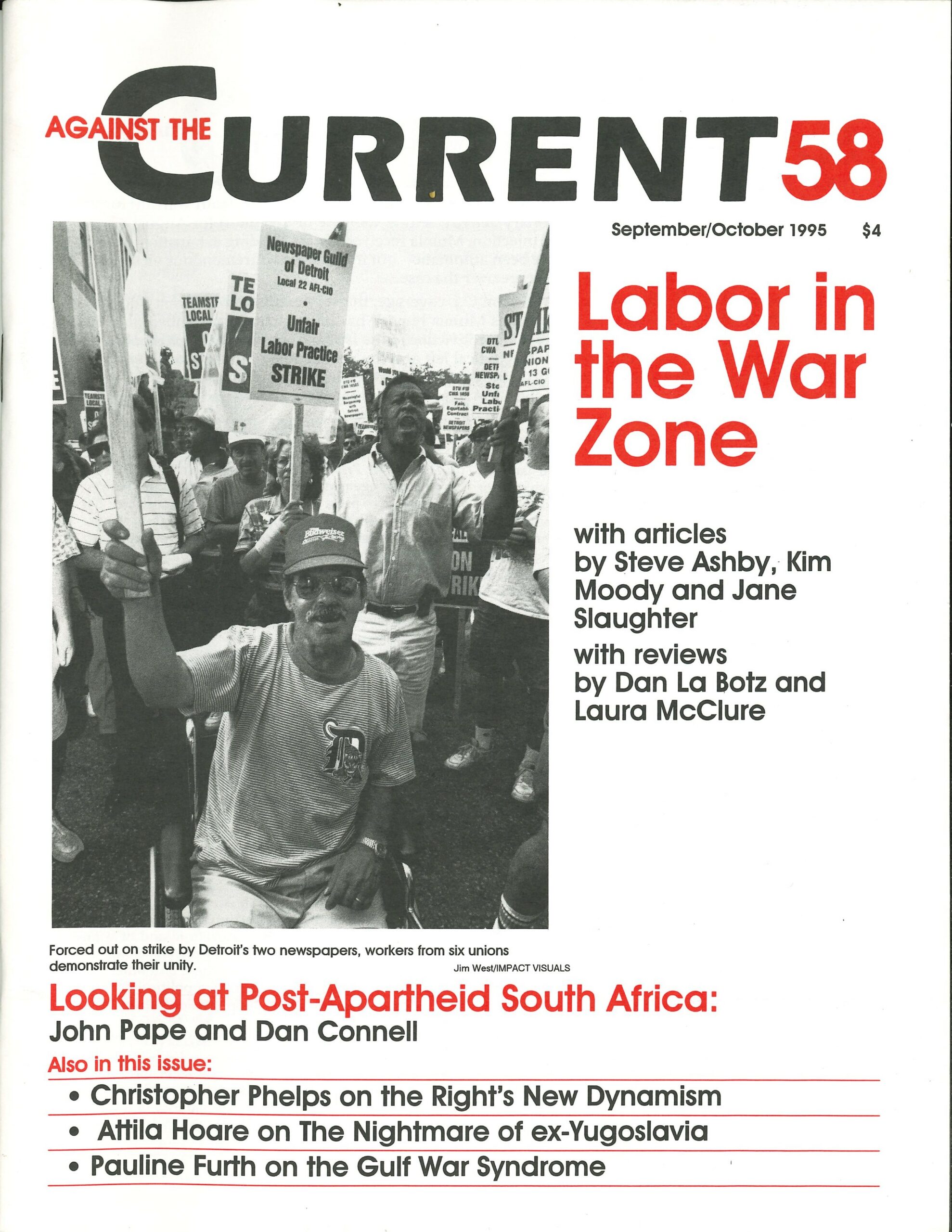

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor in the War Zone

-

June 25th in Decatur

— Steve Ashby -

Staley Workers Vote to Fight On

— Steve Ashby -

Why the Industrial Working Class Still Matters

— Kim Moody -

The New American Workplace

— Jane Slaughter -

Review: Working Smart

— Laura McClure -

Review: The CIO 1935-1955

— Dan La Botz - Post Apartheid South Africa

-

A Note of Introduction

— The Editors -

Year One of the Transition

— John Pape -

What's Left of the Grassroots Left?

— Dan Connell - Reviews

-

Serbia's Flawed Liberal Opposition

— Attila Hoare - Dialogue on American Trotskyism

-

A Reply to Alan Wald

— Steve Bloom -

Our Legacy: A Reply to Critics

— Alan Wald - Letters to Against the Current

-

On "Closing the Courthouse Doors"

— Barbara Zeluck

Attila Hoare

Yugoslavia’s Ethnic Nightmare—

The Inside Story of Europe’s Unfolding Ordeal

Edited by Jasminka Udovicki and James Rideway

New York: Lawrence Hill Books, 1995, 252 pages.

BEFORE THE BREAKUP of Yugoslavia in the period 1987-91, no adequate explanation of the national question in the country under Communist rule had been provided by any historian in any language. The Western left mostly followed the Titoist line, that national inequality had been abolished and the national question solved, and showed more interest in the system of ‘socialist self-management’ than in the forces that were to bring about the dissolution of the Yugoslav federation and the dismemberment of two of its constituent republics.

The outbreak of full-scale war in 1991 found the left without the theoretical tools needed to formulate a principled response. Many of its members, unwilling to blame the catastrophe on a political system that had appeared least deformed of any of the world’s ‘socialist states,’ vented their despair, ignorance and prejudice on anything and anyone but the real culprit.

The war was variously attributed to endemic ethnic hatreds that had been kept in check by Tito’s fatherly dictatorship; to a German conspiracy to dominate the Balkans; to a Croat propensity towards fascism; or to the impact of the international capitalist system (why this same capitalist system did not bring war to any of the neighboring countries was never explained).

Serbia was seen as the last bastion of socialism in Europe and the misunderstood victim of an imperialist conspiracy. Since the Yugoslav national question had been solved under Communism, it followed that the Slovenes, Croats and Bosnian Muslims were not ‘oppressed nations;’ consequently they had no reason to seek independence or even to defend themselves from attack by Serbia, which was after all only trying to defend the Socialist Yugoslavia we all knew and loved from the machinations of the Germans, the Vatican and international capitalism.

To this day most Western socialists cannot comprehend the Bosnian or Croatian desire for independence, which they blame for the bloodshed, much as Winston Churchill once lamented how Hindus and Muslims would never have massacred each other if only India had remained within the British Empire.

Yugoslavia’s Ethnic Nightmare is a collection of essays that will dent some of these misconceptions, but unfortunately confirm many more of them. In fairness to the authors, they do speak unequivocally of Serbian genocide of Bosnian Muslims, and put the primary blame for the war on Milosevic’s Serbia, which is unambiguously presented as an aggressor. In one of the more useful articles, Stipe Sikavica describes the role of the Serbian government and army in arming and inciting Serbs in Croatia against the Croatian authorities.

Yugoslavia’s Ethnic Nightmare is a useful antidote to arguments that play down talk of genocide and aggression and thus speak of a Bosnian “civil war” between parties bearing equal guilt, the more so since it is the work of writers from Serbia. Unfortunately, it may also be cited by leftists in the West who have always been hostile to Bosnia’s struggle for survival and independence, and who now have their views confirmed by respectable members of the “opposition” in Serbia.

At first glance the book appears promising, claiming to be “Written by a team of antiwar Muslim, Croatian, and Serbian journalists and a noted Croatian historian,” to be “the first book in English to represent the voices of resistance inside the former Yugoslavia” and “to describe the causes of the conflict from the perspective of the people who live there.”

It turns out that all the contributors, except for the editors themselves, work for institutes or “oppositional” newspapers in Serbia, and the articles are mostly written from the perspective of a liberal, “oppositional” Serb nationalism. This makes them unrepresentative of the views of the majority of the “people who live” in former Yugoslavia.

Nowhere do they express the slightest sympathy or understanding for the national rights of non-Serb peoples. In their view these are not an issue, because “the concept of self-determination” when applied to Yugoslavia was “not only absurd but perilous.” (6) Rather, “the crucial issue for Yugoslavia” was “the rights of minority ethnic groups in the republics and provinces.” (9) This turns out to mean only the Serbs in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosova, since the grievances of other minorities are given no space and their rights not defended.

The international community is faulted for having “supported the right of self-determination of the former republics” (15) when it should have placed its hopes in Ante Markovic, Yugoslavia’s Gorbachev-style reformist Prime Minister. Markovic is viewed retrospectively by many liberals in the West as the man who could have saved Yugoslavia if given the chance.

Just as Gorbachev promised much but ended up using the Soviet Army against Lithuanian, Azerbaijani and Georgian movements for democracy, so Markovic presided over repression of the Albanian population in Serbian-occupied Kosova and the Yugoslav Army’s attack on Slovenia. The promises of a ‘liberal Stalinist’ leader should not be relied upon.

Kosova: Excessive Autonomy?

Slavko Curuvija and Ivan Torov turn reality on its head in their discussion of Kosova, portraying the Serb minority as victims of Albanian oppression in the years before Slobodan Milosevic seized power in Serbia in 1987. They write sympathetically of the grievances of Kosova Serbs, which were apparently “ignored by both the federal and the Serbian authorities.” (79)

They repeat approvingly the view that Kosova was granted “excessive autonomy” under Tito, and oppose Albanian self-determination on the grounds that “For Serbia, this would have meant the loss of a significant portion of its territory,” (7) ignoring the fact that this “portion of its territory” was brutally conquered by Serbia in 1912-13 and again in 1944-45, against the will of its inhabitants.

They claim chillingly that “in the decade before Tito’s death, the Albanian population in Kosova increased from forty percent to more than eighty percent.” (76) Falsehoods of this kind reflect the Serb-nationalist obsession with the higher birth-rate that has supposedly allowed Albanians to “outbreed” Serbs in Kosova, and imply that the ‘proper’ ethnic balance should be restored through the expulsion of several hundred thousand Albanians.

Curuvija and Torov, a Serb and a Macedonian respectively, make no acknowledgement whatsoever of the oppression of Albanians within their native countries. The mass meeting held in February 1988 in the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana to show solidarity with Albanian miners on hunger strike against Milosevic’s repression is described as an “anti-Serb rally.” (101)

The authors conclude that Milosevic merely manipulated Serbian fears over Kosova that were largely justified, revealing the common ground that much of the Serbian “opposition” continues to share with its President. The editors later speak of an ethnic partition of Kosova, between 200,000 Serbs and almost two million Albanians, as a “creative solution” to the problem, falsely attributing the proposal to an Albanian oppositionist, while admitting it has met with “little approval.” (231)

Serbian oppositionists can do and have done much better: Srdja Popovic has helped demolish nationalist myths about Albanian persecution of Serbs, while Bogdan Denitch has called for the separation of Kosova from Serbia.

Croatia, Bosnia: The Real Issues

In his chapter on the origins of the war in Croatia, Ejub Stitkovac devotes much space to presenting the grievances of Serbs against Tudjman’s regime in Croatia. Many of these grievances were justified, but Stitkovac concedes no legitimacy to the fears of Croats whose country was soon to be devastated and partitioned by the Serbian army.

Indeed, his article represents a Serb-nationalist critique of Milosevic, faulted for a military campaign that “consolidated the perception abroad of Serbs as nothing but aggressors” and “made it possible for flagrant human rights violations perpetrated by Tudjman’s forces to be disregarded by the international community” (163). Stitkovac claims that “a half million Serb civilians had to abandon their homes to escape Croatian reprisals” (163), an implausible figure given that at no point in the war did the total number of Serbs in Croatian-controlled territories even approach half a million.

Though he condemns Serbian aggression and the atrocities inflicted on Croatian civilians, Stitkovac’s sympathy for Croat victims does not extend beyond the purely humanitarian level. He shares with Milosevic an opposition to Croatia’s right to independence, even though this right was guaranteed by the Yugoslav constitution, and though independence was the will of the overwhelming majority of Croatian citizens as expressed in a free referendum.

Most “oppositional” journalists in Serbia still seem unable to support the democratic and constitutional rights of the citizens of other republics.

The editors argue against Croatian independence on the grounds that Croatia had not provided sufficient guarantees for the rights of its Serb minority. Had the international community insisted on such guarantees, they claim Milosevic would have lost his justification for the war.

The insincerity of this argument is made apparent by the treatment of Bosnia. The Bosnian government gave full guarantees of the rights of its Serb citizens. This prevented neither the Serbian attack, nor a condemnation of Bosnian independence by the authors of Yugoslavia’s Ethnic Nightmare.

Udovicki and Stitkovac repeat two Serb-nationalist falsehoods: that Bosnian Serbs voted “one-hundred percent” against Bosnian independence (171); and that the proclamation of Bosnian independence was therefore illegitimate since it was a “violation of the Bosnian constitutional principle requiring the consent of all three Bosnian nations in far reaching decisions such as secession.” (175)

In fact, the great majority of Serbs in cities like Sarajevo and Tuzla voted in favor of independence. Elsewhere both Serbs and non-Serbs were prevented from voting in the referendum on independence by the paramilitary forces of Karadzic’s Serb Democratic Party, which had no constitutional right either to represent all Bosnian Serbs or to veto Bosnian independence.

Udovicki and Stitkovac acknowledge that the alternative was for Bosnia to join Milosevic’s Greater Serbia, but believe this represented the lesser evil, though it would presumably have violated the “constitutional principle” requiring the consent of Bosnian Croats and Muslims for a decision of this kind. They argue that for Serbs both in Serbia and in Bosnia, “self-determination, for historical reasons, had special significance.” (175) It did not apparently have similar significance for non-Serbs.

Strong condemnations by several contributors of Croatian aggression in Bosnia provoke mixed feelings. Certainly Croatian President Tudjman has pursued an expansionist policy in Bosnia involving mass killings. But the facts do not bear out the editors’ claim that “the Yugoslav conflict was in fact a conflict between two conceptions of strident ultranationalism, one propounded by the Serbian regime, the other by the Croatian.” (9)

Milosevic’s goal of a Greater Serbia is supported by all the major political parties in his country, none of which recognizes Bosnia’s independence or territorial integrity. His aggression against Bosnia was planned and executed uncompromisingly from the start.

Tudjman’s anti-Muslim brand of ultranationalism is not shared by any Croatian opposition party, all of which oppose the partition of Bosnia. Tudjman and the anti-Bosnian faction within his regime have precisely lacked popular backing for their expansionism, forcing them to pay lip service to Bosnian independence and vacillate between alliance with Bosnia and underhand collusion with Serbia.

Unlike the a priori Serbian aggression, the Croatian attack could have been avoided if the Western powers had thrown their weight behind the majority in Croatia by refusing to endorse the partition of Bosnia. Instead, the Vance-Owen Plan of 1993 offered major territorial concessions that encouraged and legitimized Croat irredentism. Even so, over ten times as many Bosnians were killed through the Serbian aggression as lost their lives on both sides during fighting between Bosnian and Croatian forces.

Serbian forces today occupy territory almost equal in extent to the free areas of Croatia and Bosnia combined. One cannot help suspecting that commentators from Serbia who insist so strenuously on the equal guilt of Croatia are trying above all to shift the burden of blame, the more so since they do not mention any ‘mitigating factors’ for Croat nationalists as they do for their Serb counterparts.

Western Complicity

Yugoslavia’s Ethnic Nightmare makes few criticisms of the West’s response to the conflict, and none of its conciliation and legitimization of Greater Serbia, or its complicity in the dismemberment of Bosnia.

The contributors object only to the recognition of Bosnia and Croatia, victims of the aggression of the very Serbian regime to which they claim to be an “opposition.” They argue for the need to appease Serbian nationalism. If only Milosevic and Karadzic had been denied the pretext for war presented by Croatian and Bosnian independence…

Mention is darkly made of the fact that Bosnia was recognized on 6 April, the anniversary of Hitler’s bombardment of Belgrade in 1941, apparently adding insult to injury for the Serbs. 6 April was also the anniversary of Sarajevo’s liberation from the Nazis in 1945, but this is passed over.

The West is condemned for having favored Croatia over Serbia; this might surprise most Croats, given the economic sanctions, arms embargo and six-month denial of international recognition inflicted on Croatia following its June 1991 declaration of independence.

With the Vance Plan of December 1991, the Western powers forced Croatia to accept a permanent ceasefire just when the Serbian army was on the verge of collapse; since then they have combined threats and bribes to dissuade the Croatian regime from fighting to regain its lost territories, even while the Serbian occupiers continued to consolidate their control of these territories under cover of the United Nations.

The arms embargo against Bosnia is defended on the grounds that its acquisition of arms, combined with promises of American support, “had become disincentives for the Bosnian government to seek peace.” (227) Attempts by the Bosnian government to recapture lost territories are opposed, the editors hoping that “economic reality” alone will “render ethnically pure fiefdoms or reservations obsolete.” (235) Decades of “reality” have not, of course, ended ethnic partition in Ireland, Cyprus or Palestine.

National Democratic Rights

It saddens me to have to write in this way about people who seem to be genuinely horrified at the crimes committed against non-Serbs (other than Albanians). The book is above all a testament to the failure of the Titoist project in Serbia: After forty-five years of Titoism based supposedly on the “right to self-determination, including the right of separation,” even relatively sophisticated “oppositionists” are often incapable of comprehending principles of national democratic rights; of making the jump from opposing Serbian aggression to supporting the rights of its victims.

Several contributors criticize the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution that increased the sovereignty of the republics and reduced Serbian control over Kosova, claiming “pressure from Slovenia and Croatia” had led to a constitution that “crippled” the federal government, with each federal unit “tak[ing] account only of its own needs” so that “none worried about the common household.” (75)

The current catastrophe is said to have its “roots” in the 1974 Constitution (75)–the Titoist regime is thus faulted for giving the Yugoslav peoples too much freedom. This is the fundamental misconception shared by leftists both in Serbia and in the West: Granting freedom to subject peoples just allows them to destabilize the “common household” and eventually to start killing each other; far better to deny them freedom.

There are many national traditions that give rise to such misconceptions: the Serbian tradition of ‘liberating’ smaller Balkan neighbors from German or Turkish influences; the British tradition of conquering large parts of Africa and Asia to ‘introduce’ the natives to parliament and cricket; the American tradition of burning down villages in Indochina in order to ‘save’ the inhabitants from Communism; and above all the left-wing tradition of supporting the Red Army’s ‘defense of socialism’ in Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

The peoples of Bosnia and Chechnya are paying the price for illusions of ‘multi-ethnic empire’ that prevent socialists and liberals from speaking out for the victims of Belgrade and Moscow. Peace will come to the Balkans not as a result of antiwar activism, or the avoidance of provocations to Serb nationalists, or the restoration of some form of Yugoslavia, but only when Croatia, Bosnia and Kosova are freed from occupation through defeat of the oppressor.

Recent victories of the Bosnians around Bihac and at Mt. Vlasic, and of the Croatians in Western Slavonia, show that this is not as impossible as it seemed a year ago.

ATC 58, September-October 1995