Against the Current, No. 56, May/June 1995

-

Affirming Affirmative Action

— The Editors -

Smithsonian Exhibit of the Enola Gay: The Incineration of History

— Christopher Phelps -

Was Hiroshima Necessary?

— Christopher Phelps -

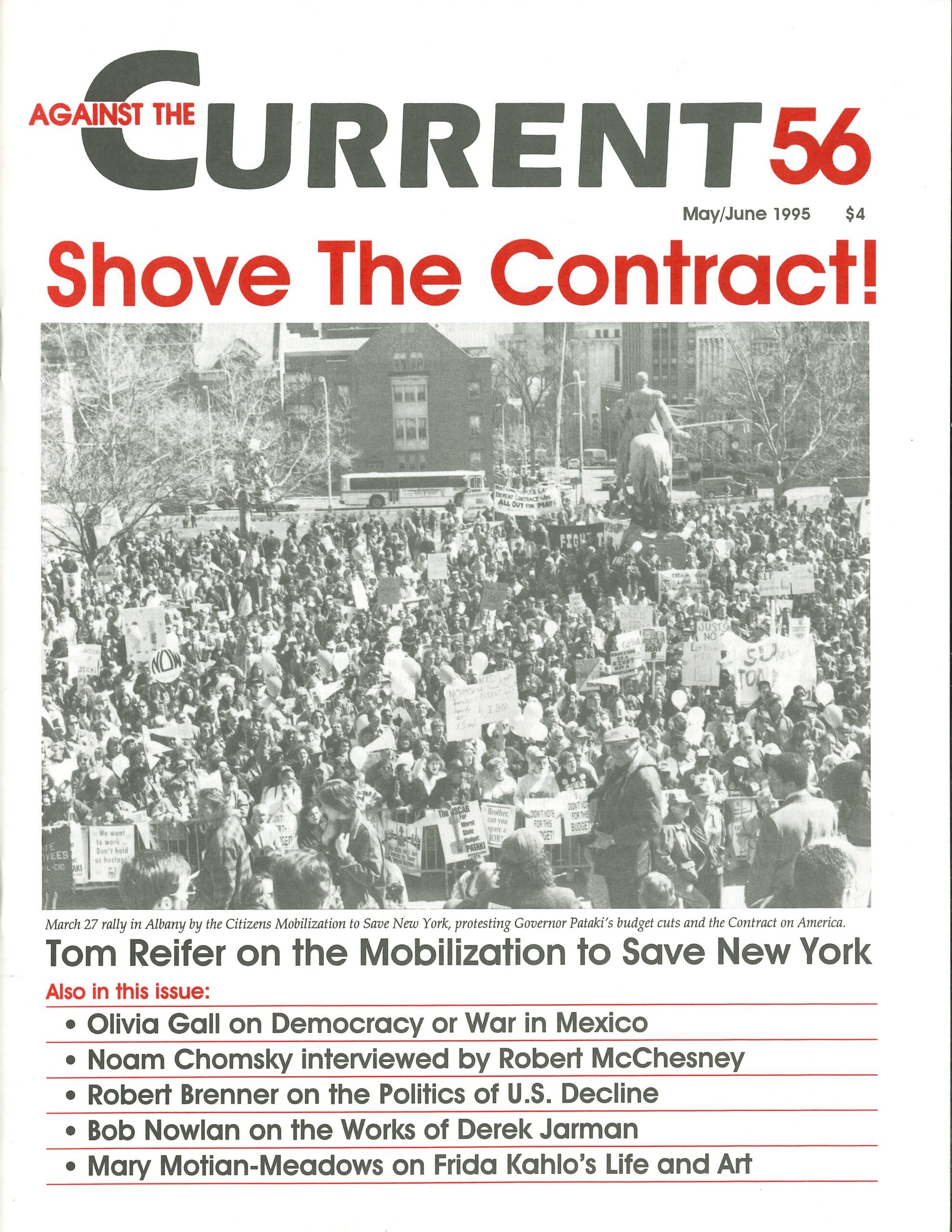

Mobilizing to Save New York State

— Tom Reifer -

The Chemical Soup in Your Cup

— Dr. Pauline Furth -

Mounting Accidents in Russia

— Renfrey Clarke -

Books for Russia: An Appeal

— Richard Greeman -

Constructing the Past in Contemporary India

— Brian K. Smith -

What Chiapas & Mexico Need: Democracy, Not War!

— Olivia Gall - Zedillo's Financial Package

-

Clinton's Failure & the Politics of U.S. Decline

— Robert Brenner -

The Media, Politics & Ourselves (Part 2)

— Robert McChesney interviews Noam Chomsky -

Reflections on the Life & Work of Derek Jarman

— Bob Nowlan -

Kahlo As Artist, Woman, Rebel

— Mary Motian-Meadows -

Radical Rhythms: The Merle Haggard Blues

— Terry Lindsey -

The Rebel Girl: Taking It to the Hoop

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Icons of Our Times

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

Mapping Solzhenitsyn's Decline

— Alan Wald - Dialogue

-

Perspectives on the ex-Soviet Union

— John Marot -

Misunderstanding Capitalism

— Alex Callinicos -

A Reply to Callinicos on the State & Capital

— Kim Moody

John Marot

ALEXANDER SOLZHENITSYN uttered the essential truth when, in a speech to the Duma last summer, he declared that the country was still run by Soviet-era “nomenklatura turncoats disguised as democrats.” The turncoats, with Yeltsin at their head, are defending their political supremacy within the prevailing “command administrative” economy, not in opposition to it. The much-touted transition to capitalism coming about as a result of the actions of the bureaucratic rulers themselves has failed to materialize.

Even the semblance of a transition is absent: Not a single free-marketeer remains in Yeltsin’s cabinet. And while the bureaucracy makes a public show of systematically attacking the symptoms of disastrous economic decline, their root cause — bureaucratic rule — is itself defended by means of those very attacks.

The nomenklatura has not, is not, and will not invest its scarce political capital into transforming itself and society. On the contrary, it is Stalinism — minus “Marxist-Leninist” phraseology and iconography — that is currently being revived with a vengeance: the corpses of thousands of Chechnian men, women and children bear silent witness to this dark fact. “The idea of change is being replaced with the idea of order, and human rights by a police state.”(1)

The Western mass media has given a semblance of reality to capitalist transformation in the former Soviet Union. It does everything to echo and magnify remarks made by Yeltsin spokesmen, and others, about the superiority of the “market” and the evils of the “administrative-command” economy (remarks that are usually timed with the arrival of IMF representatives). In sum, the virtual reality of the bourgeois corporate media depicts capitalism and freedom as struggling to self-synthesize out of the alleged chaos.

Unfortunately, much of the left has become a prisoner of this bourgeois view because the left and the bourgeois media have taken at face value what leaders in Russia have said about capitalism and markets. That is, the left has attributed to these notions the scientific meaning they possess for socialists and Marxists, not the bureaucratically twisted meaning Yeltsin and Company attribute to them.

The complicated process of bureaucratic reorganization and regeneration can be traced back to the summer of 1989, at the height of glasnost, when a huge miners’ strike rolled across Russia, Siberia and the Ukraine. For a brief moment workers organized themselves independently of the bureaucracy, and began to move toward workers’ control over the economy. Their historic action refuted fashionable talk in certain quarters that workers did not have “socialist vision.”

The bureaucracy itself saw that vision, and felt threatened by it. But it lacked, at the time, the ability or willingness to defend itself against popular protest through sustained coercion — “Stalinism.” The ruling elites therefore had no option but to resort to new, untested strategies of defense, and to develop new political institutions, to maintain control. And they have been, on the whole, strikingly successful.

The Soviet Union as a unified political entity no longer exists but the bureaucratic property relationships that characterized the former Soviet Union still do. The bureaucratic class which ruled the Soviet Union’s fifteen constituent Republics continues to do so, but the form of the bureaucratic state at the republican level has been modified, to include the trappings of democracy and party-political competition. The “administrative-command” economy has also been reconstituted, at a lower level of political aggregation, within each of the republics, with some variations.

In sum, the bureaucracy has restructured its political institutions, or state forms, to undermine or forestall the self-organization of the working class, just as, in the capitalist world, capital has restructured itself economically on an international scale to render traditional working-class organization and strategies largely powerless to defend wages, working condition and hours.

It is true that the monopoly of politics once held by the Communist Party has been shattered and political conflicts have broken outside the traditional bounds. The Communist Party, at one point “banned” by a section of its own leadership, is now one party among others. Yet the bureaucracy is still in the saddle, undermining theories that bureaucratic rule could only exist through the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. These theories were faulty because they were based on the false assumption that if conflicting currents of opinion and private interests inside the bureaucracy ever battled it out outside the party, then bureaucratic rule was in a state of incipient collapse. Events have not borne out this analysis.

To develop somewhat what I have previously argued,(2) as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union incorporated and rooted itself in ever wider layers of the bureaucracy, the bureaucracy itself responded and developed to a point where all currents of opinion and all private bureaucratic interests could take the formal step of creating parties of their own, formed on the basis of non-class distinctions — primarily ethnic and national — to advance the interests of the bureaucratic state they all belonged to. As ever more numerous cliques of this class sought representation, it became less possible, or necessary, for the Communist Party to function as the bureaucracy’s unique representative.

But it was only the real and potential mobilization of the working class that broke the traditional molds through which the bureaucracy had hitherto exercised it political supremacy. Working- class pressure pushed the bureaucracy to actually form separate, ethno/national parties, along with the corresponding ethno/national territories.

The elites moved to head off any further development of working-class self-organization and democracy by channeling the workers’ movement into authentically nationalist directions (the Baltic countries) or pseudo-nationalist ones (Belarus), and by constructing national bureaucratic parliamentary states at the republican level.

Broadly speaking, the bureaucracy rules in each of the republics because it is the bureaucratic state that organizes political institutions, and it is the state that controls the economic resources for political organizing. So long as the ruling class has the economic wherewithal to determine the political agenda of electoral campaigns which, again, means control of the state, it can tolerate democracy and democratic institutions.

Such a bureaucratic state can enjoy a inwardly secure existence as long as workers do not organize around their class interests, as workers. And this is what one sees: Primarily ethnic, national and pseudo-national interests battling it out in elections. Boris Kagarlitsky has rightly called this a “theater of the absurd” — hundreds of “parties” atomistically competing on the electoral stage.

An array of bureaucratic cliques has worked hard and long to ensure that these political theatrics only serve their interests, not the interests of working people, Russian and non-Russian. For the bureaucratic interest is not a discrete interest that is competing on a par with other, non-bureaucratic, working-class interests, let alone capitalist interests.

Currently prevailing over and against the multitude of competing special interests in elections are the class interests of the bureaucracy as a whole — because the competition of interests in the parliamentary-electoral arena is itself structured by the continued presence of bureaucratic property relationships, the fusion of state and society. It is not elected parliaments that run the state, but the state that runs the elected parliaments.

It is in connection with the formation of a bureaucratic parliamentary state that the so-called transition to capitalism acquires its full significance. To preserve its position the bureaucracy wants working people to associate democracy with bureaucracy, not capitalist property relationships.

By mimicking Western, bourgeois democracy, by parroting a hodgepodge of bourgeois sounding phrases (and calling this mishmash an up-to-date “modernizing” ideology), the bureaucracy accomplishes its supreme goal: to alienate workers from real politics and real democracy. On the other hand, workers fought for democracy and free elections not just because it was a sine qua non for the self-development of their class, but also because a higher standard of living in the West is thought by them to be directly tied to the form of the state — democracy and free elections — instead of capitalist property relations, as is actually the case.

So workers and bureaucrats have ideally separated out and selected different aspects of Western capitalist societies that seem to speak to their material interests. Unfortunately, many people in the West ignore this differential and selective appropriation of capitalist reality. As a result, they give the false impression that just about everybody in Russia wants capitalism sic et simpliciter.

In fact it is the bureaucracy which has fused these aspects into a concrete, materially effective unity: bogus democracy, bureaucratized through and through and decorated with the trappings of elections and formal democratic procedures, plus a miserable, and falling standard of living for workers.

This powerful combination has quickly generated the all-round alienation of the direct producers from politics, from the state. Electoral participation has plunged, with less than fifty percent voting in many elections, a feat rivaled only in the United States, where the disenfranchisement of the citizenry has reached troubling proportions.

The ruling elite wants to foster and maintain the alienation of the working class, not to establish capitalism. So long as the bureaucracy is able to realize this immanent objective any movement toward a democratic socialism is blocked. Therein lies the real victory for the bureaucracy. Yeltsin, Zhirinovky and others are already collecting the fruits of this victory in Chechnya.

People are legally free, at least for now, to be politically active in parties and groups of their choosing. Moreover, the bureaucracy continues to have trouble enforcing discipline among its own members, as the rise of “crime” indicates. So long as this is so, it will have a difficult time developing the forces of production.

This problem is two-fold: coordinating a bureaucratically enforced regional division of labor that is undermined by autarchic tendencies developing across all regions; and extracting a surplus from the direct producers. Getting the workers to work in an economic system where job security remains largely intact is extremely difficult — unless workers feel they are masters of the economy. Since they clearly are not, and the threat of unemployment is largely absent, the only way out is to force workers to work is through political means.(3) A tendency toward a populist authoritarianism, not free markets, is built into this situation.

The current situation is highly unstable but all indications point to a stabilization along restorationist, neo-Stalinist lines. Whether the bureaucracy will actually reach this goal will depend on how well workers can organize resistance. The outlook is not promising. We must begin to fear for the personal safety of all democrats and socialists in Russia, not excluding those who have contributed to Against the Current, and to other progressive journals in the West.

Notes

- Boris Kagarlisky, “Yeltsin’s War of Genocide,” ATC March-April 1995, 8.

back to text - “What Glasnost’ Is, And Is Not,” ATC January-February 1990.

back to text - According to official figures, unemployment is extremely low, approximately 1.5%, and has virtually not budged in nearly three years, i.e., since the beginning of the so-called market reforms. This is because the drop in demand for labor has been accompanied by an equally sharp drop in wages. Production has fallen by one-third in the last three years but the bureaucracy has recouped by forcing wages down by one-third as well. In other words, since workers have become much less costly there is much less incentive to cut costs by firing them. Moreover, current labor and tax laws favor retention of workers on the payroll: Compulsory severance pay is high, and a tax on excess wages means managers have an incentive to employ lots of people at low wages rather than a few people at high wages. Finally, many workers are prepared to accept huge monetary wage-cuts because a good part of their subsistence is directly allocated by the unit of production they work for, above all, housing, health care, and food (cafeterias). If they quit, they lose this.

back to text

ATC 56, May-June 1995