Against the Current, No. 56, May/June 1995

-

Affirming Affirmative Action

— The Editors -

Smithsonian Exhibit of the Enola Gay: The Incineration of History

— Christopher Phelps -

Was Hiroshima Necessary?

— Christopher Phelps -

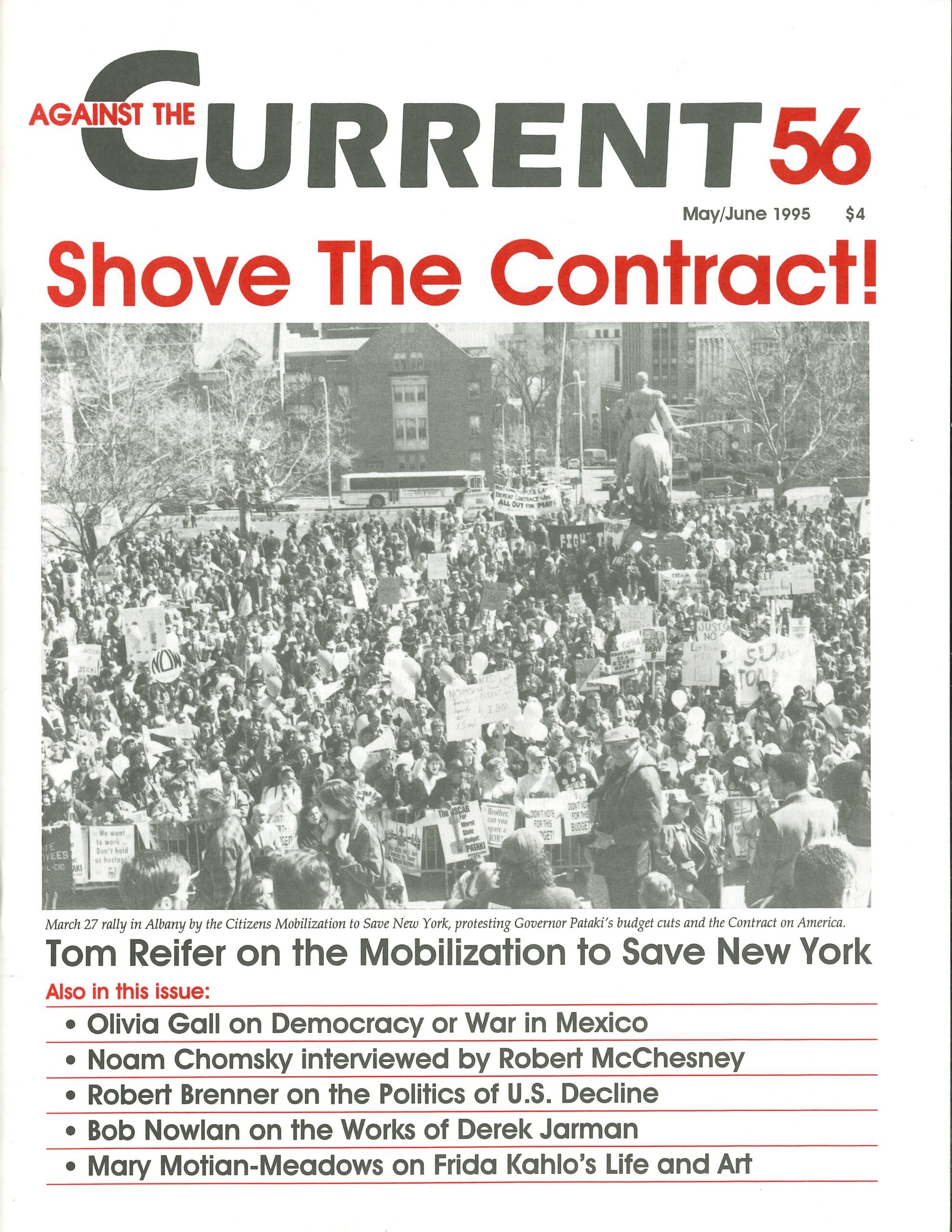

Mobilizing to Save New York State

— Tom Reifer -

The Chemical Soup in Your Cup

— Dr. Pauline Furth -

Mounting Accidents in Russia

— Renfrey Clarke -

Books for Russia: An Appeal

— Richard Greeman -

Constructing the Past in Contemporary India

— Brian K. Smith -

What Chiapas & Mexico Need: Democracy, Not War!

— Olivia Gall - Zedillo's Financial Package

-

Clinton's Failure & the Politics of U.S. Decline

— Robert Brenner -

The Media, Politics & Ourselves (Part 2)

— Robert McChesney interviews Noam Chomsky -

Reflections on the Life & Work of Derek Jarman

— Bob Nowlan -

Kahlo As Artist, Woman, Rebel

— Mary Motian-Meadows -

Radical Rhythms: The Merle Haggard Blues

— Terry Lindsey -

The Rebel Girl: Taking It to the Hoop

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Icons of Our Times

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

Mapping Solzhenitsyn's Decline

— Alan Wald - Dialogue

-

Perspectives on the ex-Soviet Union

— John Marot -

Misunderstanding Capitalism

— Alex Callinicos -

A Reply to Callinicos on the State & Capital

— Kim Moody

Brian K. Smith

SINCE GAINING INDEPENDENCE in 1947, India has constitutionally defined itself as a “sovereign, democratic and secular republic.” With its current population of 850 million people, comprised of an enormous variety of ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious groups, modern India has been proud of its status as the world’s largest functioning (more or less) democracy.

Today, this society is undergoing a traumatic identity crisis, facing a momentous decision as to what kind of nation it thinks it is — a secular democracy or Hindu theocracy — and what kind of past it thinks it has. Over the last decade a growing and militant faction within the Hindu majority has challenged some basic assumptions of the Indian polity, and the Hindu religion.

The religious affiliation of up to 83% (estimates vary) of India’s people, Hinduism until recently had pursued a policy of tolerance and open-mindedness toward the nation’s Muslims (over 100 million, the third largest aggregate of Muslims in the world), Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians and other minorities.

In part, perhaps, because it lacks an institutional orthodoxy or organized church, Hinduism seemed suited to the needs of a multicultural and religiously diverse nation-state.

In December 1992, however, events over the past few years came to a head when a sixteenth century Muslim mosque in Ayodhya was destroyed by a crowd of Hindu fanatics. Murderous large-scale riots followed, with casualties numbering in the thousands; in January 1993, a week of uncontrolled (though not necessarily spontaneous) violence erupted in Bombay, leaving hundreds dead and the country’s most cosmopolitan city in shock.

In February of that year, thousands were arrested in Delhi as a frightened government prevented an opposition party march on the capital by suspending civil liberties. In March a series of bombs rocked Bombay’s stock exchange, luxury hotels, national airlines office building and other commercial and public places, as another 300 perished and countless millions of dollars of business were lost.

The conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), riding the wave of Hindu resentment and militancy, has been the chief beneficiary of the chaos, moving in a few short years from political fringe to its present position as the major opposition to the ruling Congress Party.

The success of the BJP is due, in part, to its ability to offer disgruntled Hindus a new interpretation of India’s national identity — based on a new representation of its part. Its success is also bound up with a very extensive network of ties to “lumpen” elements in the cities, who round up their locals for rallies, processions and elections, and the party’s extensive patronage schemes, which dole out food and medicine in poor areas.1

Many pillars of India’s national self-image have been shaken in this effort to remake the country’s character. One principal target has been the notion of India as a secular state, a “construct” devised by the father of the nation Jawaharlal Nehru.

Among the most important of the BJP’s contentions is that India’s version of secularism — which means here not official irreligion, but rather tolerant neutrality toward all religions — is a foreign import, grafted unnaturally onto Indian soil by the hyper-modern Nehru and his jet-setting successors. Hinduism, this argument runs, is so intrinsically tolerant that there is no need to “import secularism” in order to protect and ensure freedom of religion; Hinduism, when elevated to the state religion of India, will itself carry out that protective function.

More important still, critics say, secularism in India has served merely as a sham for appeasing minorities and for craven pandering to “vote banks” of grateful Muslims on the part of politicians. They point to the aftermath of the so-called Shah Bano case, when then-Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi overruled the Indian courts and upheld a Muslim man’s right to be governed by religious, not civil, divorce law.2

India, the BJP insists, is a “Hindu nation” and always has been. One of the principal leaders of the BJP, L.K. Advani, has suggested that Muslims, Christians and Sikhs living in India be referred to as “Mohammadi Hindus,” “Christian Hindus” and “Sikh Hindus” in order to emphasize the ancient and persisting Hindu character of the Indian nation-state. A Hindu writer and publisher to whom I spoke in Delhi said that Muslims could stay in a Hindu India, but first must “be stripped of their Islam.”

This kind of word-play is unappreciated by India’s Muslims who, at the time of the partition of the formerly British colony into an Islamic Pakistan and a secular India, cast their lot with the latter. It should be remembered here that British colonialism for generations sought to defeat Indian independence by setting Hindus and Muslims against each other — and that millions of secular-minded Muslims were an integral part of the anti-colonial struggle.

These Muslims have been, and always will be, Indians for life. Their histories don’t need to be reconstructed — they’re there — as is the fact that Muslims share the same culture and languages with Hindus and have lived in India for centuries. Yet they now find themselves labelled “foreigners.” Bal Thackeray, an admirer of Adolph Hitler and leader of the Shiv Sena (“God’s Army”) which was behind much of the violence against Muslims during the January 1993 Bombay riots, declared that Muslims must be expelled from the “Hindu motherland.”

In a well-publicized interview Thackeray compared India’s Muslims to the Jews: “Have they behaved like the Jews in Nazi Germany? If so, there is nothing wrong if they are treated as Jews were in Germany.” Among other things at stake in the crisis in contemporary India, then, is the future of Hinduism.

Hinduism’s traditionally tolerant demeanor and all-embracing doctrinal stand is giving way to a new fundamentalist outlook. Hinduism, it is sometimes ironically observed, is becoming “Islamized:” Politically-oriented Hindu holy men are functioning as imams, Ayodhya (the supposed birthplace of the deity Rama) is becoming a Hindu mecca, and a Hindu version of holy war is being fought against Muslims in India’s cities.

“The Political Abuse of History”

To reinvent the present one must reinvent the past, and Hindu activists have been hard at work doing just that. If Muslims are to be reconstituted as “foreigners” and Hindus as the true and indigenous Indians, the inconvenient fact that the ancient forebears of Hinduism, the Aryans, came originally as invaders of the subcontinent from a probable homeland in the Russian steppe lands must be adjusted.

At a conference held in January 1993, right-wing historians associated with the BJP introduced a new and more politically serviceable version of the archaic past: The Aryans were native to India all along, and their successors therefore are the rightful inheritors of the land.

It was also the BJP and its affiliated organizations who were responsible for stirring up the religious fervor that resulted in the destruction of the mosque at Ayodhya. Muslims are not only branded outsiders in “Hindu India,” but are also blamed for the supposed anti-Hindu acts of Mughal emperors who ruled north India some 400-500 years ago.

Ayodhya, it is claimed, is the actual birthplace of a supernatural Hindu deity. The god Rama was born, according to BJP historians, sometime during or before the third millennium B.C. In the sixteenth century, or so the story goes, the Islamic ruler Babur destroyed the Hindu temple dedicated to Rama, which had existed since time immemorial, and erected on its ruins a mosque. It is this structure that was pulled down in six hours, by hand, by thousands of Hindu nationalists on December 6, 1992.

The BJP has marched out its own historians and archaeologists to provide official validation of its claims about Ayodhya. A certain Sudha Malaiya, described in a press release as a “young and bright art historian,” was put on display to tell the nation about the remarkable archaeological finds she personally uncovered on the day the mosque was destroyed.

This evidence — including pillars from the ancient Hindu temple astonishingly left wholly intact, and a perfectly preserved large sandstone slab bearing inscriptions in Sanskrit — not surprisingly confirmed all the main points of the BJP renditions of Ayodhya’s past. The miraculous nature of these finds was immediately noted, and their authenticity disputed, by experts of a more secular bent.

Especially suspicious were those who had worked for years on systematic archaeological expeditions which had turned up nothing that remotely suggested that the site held such antiquarian wonders and indisputable proof for religious beliefs. Professor B.B. Lal, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, conducted one such excavation in the 1970s and concluded that there was absolutely no evidence of any pre-existing Hindu temple.

Historians at the prestigious and left-leaning Jawaharlal Nehru University also joined the fray, publishing pamphlets and newspaper articles in an attempt to discredit the BJP account of Ayodhya’s past. In a publication entitled “The Political Abuse Of History,” the faculty of JNU’s Centre for Historical Studies write that “when beliefs claim the legitimacy of history, then the historian has to attempt a demarcation between the limits of belief and historical evidence.”

They also conclude that, although it is “quite plausible that there was a structure somewhere in the vicinity,” there is no proof that a Hindu temple once occupied the controversial spot at Ayodhya.

Hindu extremists have countered by broadening and diversifying their efforts — distributing a list of 3000 sites across the country where, they claim, Muslim emperors usurped sacred Hindu ground. Some of these could well become the Ayodhyas of the future, one likely target being a 17th-century mosque in the Hindu holy city of Benares.

Other revisionists have gone so far as to assert that the Taj Mahal itself was not built by a Mughal emperor to commemorate his wife, but was in fact a pre-Islamic Hindu monument appropriated later by the insatiable Muslims. Several years ago, 30,000 Hindus burst into the popular tourist attraction with the intent of “recapturing” and “converting” it.

Priests have taken to chanting Sanskrit verses within the Taj, apparently in the attempt to transform one of the seven wonders of the world into a Hindu temple. Cheap plastic replicas are now for sale, with the Islamic crescent moon that adorns the top of the real monument replaced by a trishul, a Hindu trident.

Who Are “We”?

The battle for India’s past has also been waged in the classrooms of elementary and high schools. Textbooks in the states once controlled by the BJP were rewritten so as to glorify the “Hindu past” and excoriate the policies of “Muslim invaders.” In the Indian version of “linguistic cleansing,” cities and other locations with non-Hindu names were given new designations, more in keeping with the fundamentalist vision of the country. Thus Delhi has become “Indraprasth,” Lucknow is renamed to “Lakshmanpuri,” and the Arabian and Indian Oceans are now respectively “Sindhu Sagar” and “Ganga Sagar.”

The conflict over the past is, and is more than, a war of words. If, for example, the BJP and its supporters succeed in the quest to make “Indian” and “Hindu” interchangeable terms, it will not be just the Muslims of India who will come to mourn the loss of secularism in the world’s largest parliamentary democracy. India very likely would be plunged into civil war, and quite possibly entangled in a potentially nuclear conflict with its Muslim neighbors.

The government billboard prominently displayed at one of New Delhi’s traffic circles declares: “India is one country. It belongs to us all.” Despite this cheery message, the identity of the “us” is no longer self-evident. Does India belong to “us” Hindus? (For all Indians, the fundamentalists will tell you, were once Hindus; Muslims, Christians and others are all converts.) Or does it belong to an Indian “us” in a different sense?

India’s understanding of its self-identity pivots today on how it understands its past, a past that is undergoing reevaluation. How this nation-state conceives or reconceives its own long history will determine whether India can survive as the world’s largest secular and pluralist democracy, or enter the new millennium as the newest and by far most populous of theocracies.

“Construct” and Reality

Reality (to cite the title of Walt Anderson’s book on the topic) just isn’t what it used to be. As we are told nowadays by the avant-garde of a whole host of academic disciplines, reality is no longer just “out there” waiting to be perceived. Reality, rather, is a fabrication of the perceiver, a construct that has been distinctively shaped and distorted by one’s many and varied cultural preconceptions, class interests, gender conditioning, sexual proclivity, racial and ethnic identity, et al.

The mother of all “social constructions of” academic works is, of course, Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann’s 1966 classic The Social Construction of Reality. But it now seems that it is not just reality as a whole that is “constructed,” but each of its parts as well.3 Meaning is socially constructed, as are power, science, adolescence, inequality and the premenstrual syndrome, along with motherhood, satanism, the apostle Paul’s public image, mass hysteria, psychoanalysis and ancient west Mexican metallurgy.

Things we once were quite sure really existed outside our own minds have now been revealed as socially constructed: disease, the environment, the body, pain, domestic space, deafness, sexual assault, weapons proliferation and death in the Gulf war. Human life, the world and everything in it are of our own making; they are all our “constructs.”

Included in this multitudinous list of things reinterpreted as products of the social imagination is<197>history. The past, too, it has become fashionable to say in academic circles, is constructed. History, it seems, is made, in more than one sense of the term.

On its face, there is a certain persuasiveness to the claim that history is a construction. What we, collectively no less than individually, wish to remember and how we wish to remember it are indeed formulated with an eye to present circumstances, and are especially tied to our present sense of identity.

As our understanding of who we are — again, both as individuals and as collectivities — changes, so does the past we choose to remember. Conversely, the past may be reconceived in order to establish a revisionist memory that helps to generate a new sense of self in the present.

For a nation, sharing common stories about the past lends a sense of unity and distinctiveness. Remembering makes it possible for a group to recognize itself as a collectivity, with a common identity and sharing a common tradition.

Consciousness of the constructed nature of the past, of the fact that history is encoded in story, is in many ways liberating. For one thing, it affords the possibility of correcting or supplementing narratives that we once transmitted about bygone times, which we no longer find adequate.

The account of the United States’ past, for example, has undergone some serious and useful revisions over the past several decades as African Americans, Native Americans, Latinos, gay, female and just plain folks Americans insist that the national story be retold to include them and their contributions.4

But dangerous potentialities are also unleashed by the recognition that memory, official and personal, is alterable. If the past is merely an interpretation, then it is certain that different forces will offer different interpretations. It is not clear how one can combat those claims about the past with which one takes issue if the premise has been accepted that all versions of the past are constructed.

Marching out the <169>evidence<170> certainly will not clinch matters; it is often precisely what counts as evidence that is under dispute. Standing on authority no longer will suffice either. If history is a matter of opinion, who’s to say whose opinion counts and whose doesn’t?

Perhaps the ability to declare what happened in the past is merely one of the privileges of power. Among the principal themes of George Orwell’s prescient dystopic novel 1984 was Big Brother’s ability to exercise “reality control,” which entailed scoring “an unending series of victories over your own memory.” “’Who controls the past,’ ran the Party slogan, `controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’”

Control over the past is indeed what is at issue in many a present struggle for power. Taking mastery over the past sometimes means by vaporizing large parts of it. In the former Yugoslavia, place names associated with unpleasant memories of foreign domination have been changed, a linguistic cleansing complementing the more publicized ethnic cleansing.

Serb ideologues even object to the name “Bosnia,” which they associate with Turkish and Austro-Hungarian rule. “By eliminating this term,” says Djordeje Mikic, a Bosnian Serb historian, “we are eliminating the memory and consequences that stem from it.”

The past, like other aspects of modern reality, may indeed be nothing more than a construct. But it does matter what kind of edifice we erect with our memories. In the case of India, how the second most populous country on earth reconfigures its own past could very well have huge ramifications for what was once optimistically called “the new world order.”

As the past is manipulated to mobilize hatreds and resentments in the present, one hopes that the library data base of the near future will not include an analysis of the “social construction” of the casualties incurred when India successfully reinvents itself as a “Hindu nation.”

ATC 56, May-June 1995