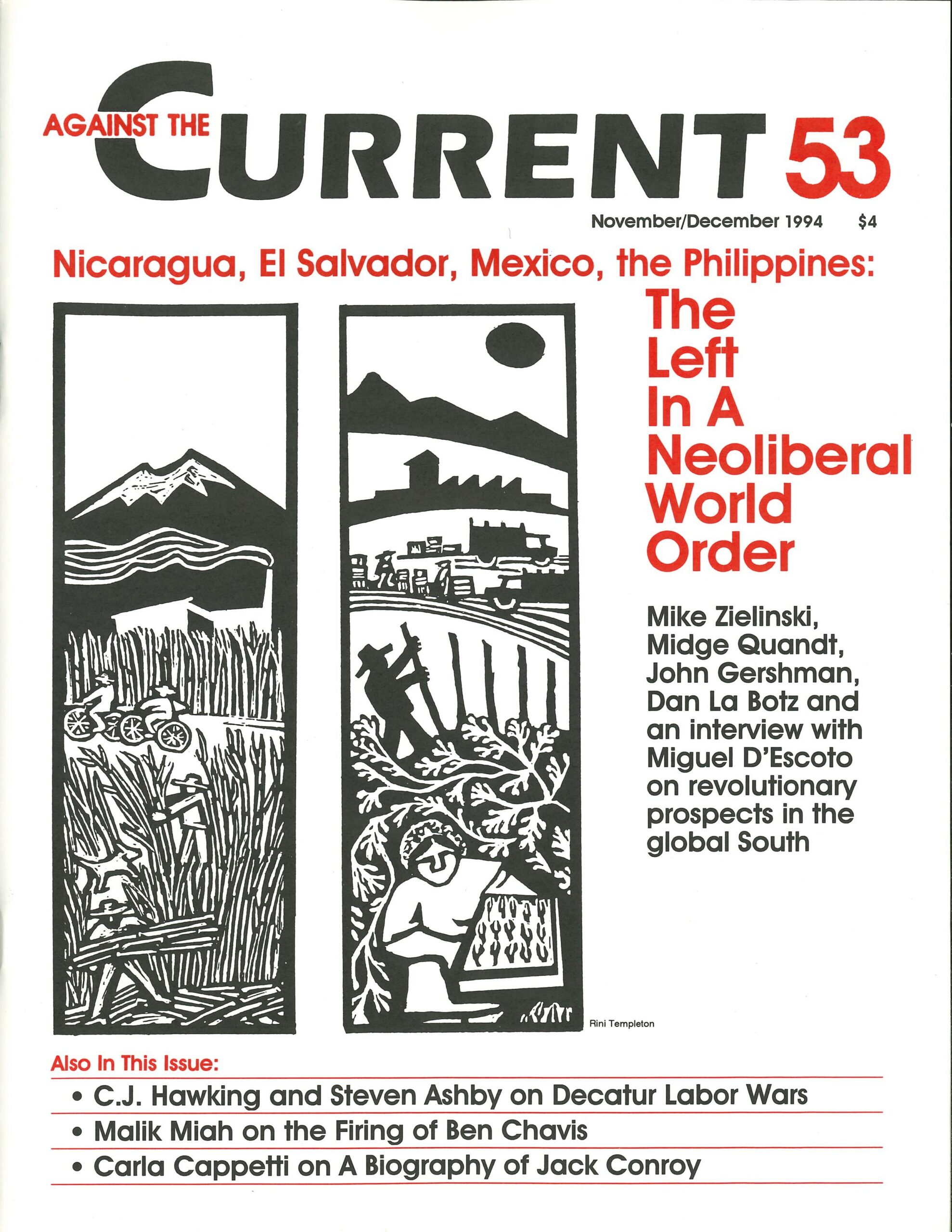

Against the Current, No. 53, November/December 1994

-

Clinton's Best-Laid Plans

— The Editors -

The Firing of Ben Chavis

— Malik Miah -

Decatur Labor Fights On

— C.J. Hawking & Steven Ashby -

Mexico: Zedillo Wins, the Struggle Continues

— Dan La Botz -

Gays & Lesbians in Chile Fight Back

— Emily Bono -

Rebel Girl: Family Planning Without Women??

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Family Values for Beginners

— R.F. Kampfer - The Left Reconstructs

-

The FMLN After El Salvador's Election

— Mike Zielinski -

El Salvador: A Political Scorecard

— Mike Zielinski -

Sandinismo's Tenuous Unity

— Midge Quandt -

Keeping the Dream Alive

— interview with Miguel D'Escoto -

Debates on the Philippine Left

— John Gershman -

The End of American Trotskyism? (Part 1)

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Massacre in the Guatemalan Jungle

— Dianne Feeley -

John Beverly's Against Literature

— Tim Brennan -

Jack Conroy, Worker-Writer in America

— Carla Cappetti - Dialogue

-

What Genovese Knew, And When

— Christopher Phelps -

On the PDS: An Exchange

— Eric Canepa -

On the PDS: A Reply

— Ken Todd - In Memoriam

-

Peter Dawidowicz, 1943-1994

— Nancy Holmstrom -

Clarence Davis, Gulf War Resister

— David Finkel -

Earning the Title

— Clarence Davis -

Desert on Detroit River (To Laurie)

— Hasan Newash

The Editors

ONE THING IS clear about Clinton’s mission to Haiti: it’s not about restoring democracy. If that were the mission, the U.S. military would not have been preoccupied with possible “looting” while demonstrations against the coup government were attacked by the paramilitary, backed by the Haitian military. As Evans Paul, Port-au-Prince’s mayor (who had been living underground during the past year), remarked, “People in this country are going to rest only when the military has been smashed to pieces. But it does not seem that is what the Americans want to do.” (New York Times, 9/25/94) In fact the Carter plan called for “close cooperation” between U.S. and Haitian military forces.

Yet U.S. military intervention does look different in Haiti than it has in, say, Central America — even if it took public pressure to get them to raid FRAPH headquarters and cart off to jail 100 or so thugs. Many who opposed the Vietnam war and the Gulf war are disoriented: we see on TV the U.S. military disarming the Haitian military and paramilitary, we see crowds joyously demonstrating as the U.S. military moves against the forces that have brutalized the population. And at the same time the Haitian “Morally Repugnant Elite” and the U.S. political establishment’s right-of-center wing oppose the occupation. Their motives are varied, ranging from worries of Aristide’s radicalism to sheer Republican opportunism — the desire to prevent Clinton from showing any successes.

How are we then to analyze the situation? Does U.S. imperialism have a new, humanitarian face? Why did the Clinton administration choose to intervene now?

This scenario might have seemed improbable, especially given that everyone in Haiti believes the U.S. embassy and its agencies (from the CIA to U.S. Aid for International Development) were involved in the coup that overthrew Jean-Bertrand Aristide. After all, Lt. General Raoul Cedras et al. were on the CIA payroll.

It is difficult in this post-Cold War world for Washington to be implicated in very long-term, out-in-the-open repressive regimes. Washington, for example, can continue to support the Balaguer government in the Dominican Republic because that is a business-as-usual repression, not a continually rising, out-in-the-open, mutilated-bodies-in-the-street repression.

Washington “lost” the 1990 Haitian election, when Marc Bazin, the candidate the U.S. backed with more than $2 million, pulled only 14% of the vote against Aristide’s 67%. Following the coup Bazin was illegally installed by the military — but he couldn’t manage to provide the necessary cover of legitimacy. So Washington’s alternative to Aristide was quickly used up.

Washington actually tried to get a settlement with Cedras. It leisurely negotiated with Cedras, while the force behind him — the elite that sponsored the Tontons Macoute under the Duvalier regime — saw no reason for restraint. So the state-sponsored terror was able to take its course before the Clinton administration gave its “final” ultimatum. This three-year wait allowed the popular movement to hemorrhage: 5,000 killed, 300,000 driven into hiding, and 40,000 who attempted to flee the island in boats — with most returned by the U.S. Coast Guard, under Washington’s racist and illegal policy, into the hands of the military.

As the brutal terror continued, however, President Aristide and the Haitian popular movement were able to force the UN, OAS and Washington to impose an embargo. An embargo was imposed on four separate occasions and, however leaky, did manage to destabilize the economy. Yet Cedras and company still showed no sign of compliance.

The majority of the Congressional Black Caucus believed that Washington could intervene on the side of good this time, helping to alter the balance of forces inside Haiti. But we maintain that is a misreading of Washington’s motives and aims. Haiti, after all, is an important source of cheap labor for the 200 U.S. businesses that employ over 100,000 Haitians. And U.S. AID has already spent over $26 million to keep it that way: It worked with Haitian businessmen during President Aristide’s government in opposing the raise of the minimum wage from fourteen to fifty cents an hour, keeping “Haitian production competitive in world markets.”

Clinton’s Program for Haiti

Washington plans for “reconstructing” Haiti are now fully outlined. They include an occupation carried out through a reorganized military and police on the one hand, and an economic restructuring, on the other. This would bring Haiti “back into line” with the rest of the Caribbean, where parliamentary democracies, having the most limited political and social content, eagerly accept a neoliberal economic program.

Now Washington demands that Aristide submit to a structural adjustment policy, to an amnesty of those who used state terror against the popular movement, and to a reorganized military and police. These conditions are an attempt to force Aristide to repudiate his demand for justice and to sever his government from the lavalas movement that is his base.

Of course most of the U.S. media lap up all of Washington’s proposals like so much cream. Why question the ability of the U.S. military w-hen they have trained and armed the Haitian army in the first place? The fiat U.S. occupation (1915-34) led to the suppression of peasant revolts, a disarming of the population, and a complete overhauling of the Haitian military. Since that time, it has been reorganized, rearmed and retrained by the U.S. military.

According to Allan Nairn’s important October 3 Nation article, Major Louis Kernisan will be in charge of retraining Haiti’s police. He sees the 565 section chiefs, who extort, intimidate, detain, arrest and sometimes kill the rural population, as, on balance, a positive force. Nairn captures Kernisan’s sensitivity to civil rights:

“Popular uprising? Under the watchful eye of 6,000 or 7,000 international observers? I doubt it. This is only the kind of shit they’ve been able to get away with when there is nobody watching….They tried that before and it brought them two years of embargo and their little guy in golden exile in the States.”

U.S. spokespeople emphasize that the worst” human rights violators will be mustered out of the army, and the force rebuilt, but it looks like the fox is in charge of the chicken coop!

U.S. tactics, however, can be pushed off center by the intervention of the popular movement in the streets of Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haitien. After initially standing on the sidelines, the U.S. military was forced by public opinion-both American and Haitian — to begin disarming FRAPH. Despite these moves, the basic U.S. goal remains the same: to insure the continuation of the police and military. Accompanying this are the economic strings.

A structural adjustment plan, presented by Aristide “advisers” Leslie Voltaire and Leslie Delatour to the World Bank last August, commits Haiti to halve its civil work force, privatize public services, slash tariffs and import restrictions, end price and foreign exchange controls, grant aid to the export sector, enforce an “open foreign investment policy,” rewrite corporate law, limit the scope of state regulation, and create special corporate courts with judges who are particularly sensitive to the problems of economic efficiency. In return, Haiti would receive $800 million in “aid,” including $80 million for its foreign debt.

Imposition of this plan jettisons raising the minimum wage, granting aid to the peasant sector, subsidizing prices so the poor would have access to basic foods, or relaunching needed health, sanitation and literacy campaigns. Although the Haitian Economic Plan promises to invest half of the proceeds from privatization in providing infrastructure and housing in the poorest areas, the promises are vague.

The Clinton administration has attempted to surround President Aristide with “advisers” like Voltaire and Delatour (a member of Baziri s cabinet when Bazin was Jean-Claude Duvalier’s finance minister and a finance minister himself under General Henry Namphy’s repressive regime), who will be able to “open doors” for Haiti in the international community. These will attempt to prevent Aristide’s government from carrying out the radical reforms it began to initiate during its first seven months of office.

In addition, Washington has also attempted to box Aristide into holding the next presidential election in December 1995, when he actually will have been in office less than two years of his five-year term. (The Haitian Constitution merely states that a president is to serve for a five-year term, and may not succeed oneself.)

What’s At Stake?

While Haiti may seem like a poverty-stricken and distant country to most Americans, it is a significant source of super profits for U.S. business. American-owned businesses forced by the embargo to shut down temporarily are impatient to reopen. As a September 27 Christian Science Monitor article quotes Robert Antoniadis, president of a hand-crafted giftware company, “I can’t think why they are making us wait another month.”

Both U.S. manufacturing and agricultural interests want to make sure Haiti is an appendage of the U.S. market: working in the assemblies to produce apparel, electronics, baseballs; growing crops and seafood for the upscale U.S. palate. It also has become a market for U.S. wheat and rice, increasingly dependent on U.S. fertilizers. In fact, U.S. State Department documents speak about how Haitian markets can be “conquered.”

Even more, in the NAFTA/GATT world order, U.S. workers are told that jobs which paid $15-20 an hour will now be done for $6 an hour. Otherwise, they’ll go to Mexican workers for $1.50 an hour; if they won’t do them, the jobs will go to Central America for seventy-five cents an hour — and if they won’t do them, then they go to Haiti for fourteen cents! In this sense, all U.S. capital feels an interest in the cheapest possible Haitian labor.

Why have so many U.S. politicians expressed so much distrust and hatred for Aristide? It’s not just an expression of racism toward a president who is Black, but also because Aristide is not a conventional politician who rose through the ranks of the political diplomatic ladder. He became the spokesperson for the grassroots movement as it flowered in the post-Duvalier period. It is a movement of peasants, trade unions, students, women, poor communities, and it is rooted in the ti legliz, the church of the poor.

Aristide’s base is the popular movement, the overwhelming majority of Haitians, whose demands cannot be met at the same time a structural adjustment policy is carried out. Those who hungered and thirsted for justice went to the polls in December 1990 and overwhelmingly smashed through “business as usual” in the Haitian state. They defended their vote in January 1991, when a coup attempted to steal it from them. And now — Clinton is gambling — they have suffered sufficiently so they will not be able to rebuild the bridge between Aristide and themselves in time.

Haiti, in short, is to be “normalized” for neoliberalism and investment. Its people are to forgive and forget — forgive the torturers, forget about justice and freedom. Of the two specific demands raised in the seven-point agreement between the illegal Haitian government and Jimmy Carter, one was over granting amnesty to the people Clinton had finally called murderers, rapists and terrorists — although he conveniently left out that they are drug runners too — and the second dealt with immediately lifting the embargo.

It’s clear what Washington’s program is. It has nothing to do with the restoration of popular democracy. Washington’s plan will continue to base itself on the five families that rule Haiti and the U.S. multinationals. What remains to be seen is whether the popular movement, no matter how bloodied, can rise and reshape itself. Solidarity activists, U.S. grassroots movements and socialists need to oppose Washington’s maneuvers. We need to express solidarity with the Haitian masses, who have fought tenaciously for generations to secure democracy and justice.

ATC 53, November-December 1994