Against the Current, No. 48, January/February 1994

-

Those Giant Sucking Sounds

— The Editors -

Voucher Mania: Will It Spread?

— Joel Jordan -

The Unmaking of Mayor Dinkins

— Andy Pollack -

The Illusion of Middle East Peace

— Nabeel Abraham -

An Information Center for the Russian Workers' Movement

— Alex Chis and Susan Weissman - Defend Human Rights in Russia!

-

On Mythology and Genocide

— Branka Magas -

Behind the Turmoil in Italy

— Jack Ceder -

The Rebel Girl: Having A Bobbitt Sort of Day?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: The Spirits of the Season

— R.F. Kampfer - Chronic Fatigue Demonstration

-

Working-Class Vanguards in U.S. History

— Paul Le Blanc -

Puerto Rico's Plebiscite

— Rafael Bernabe -

Section 936: A Corporate License to Steal

— Working Group on Section 936 -

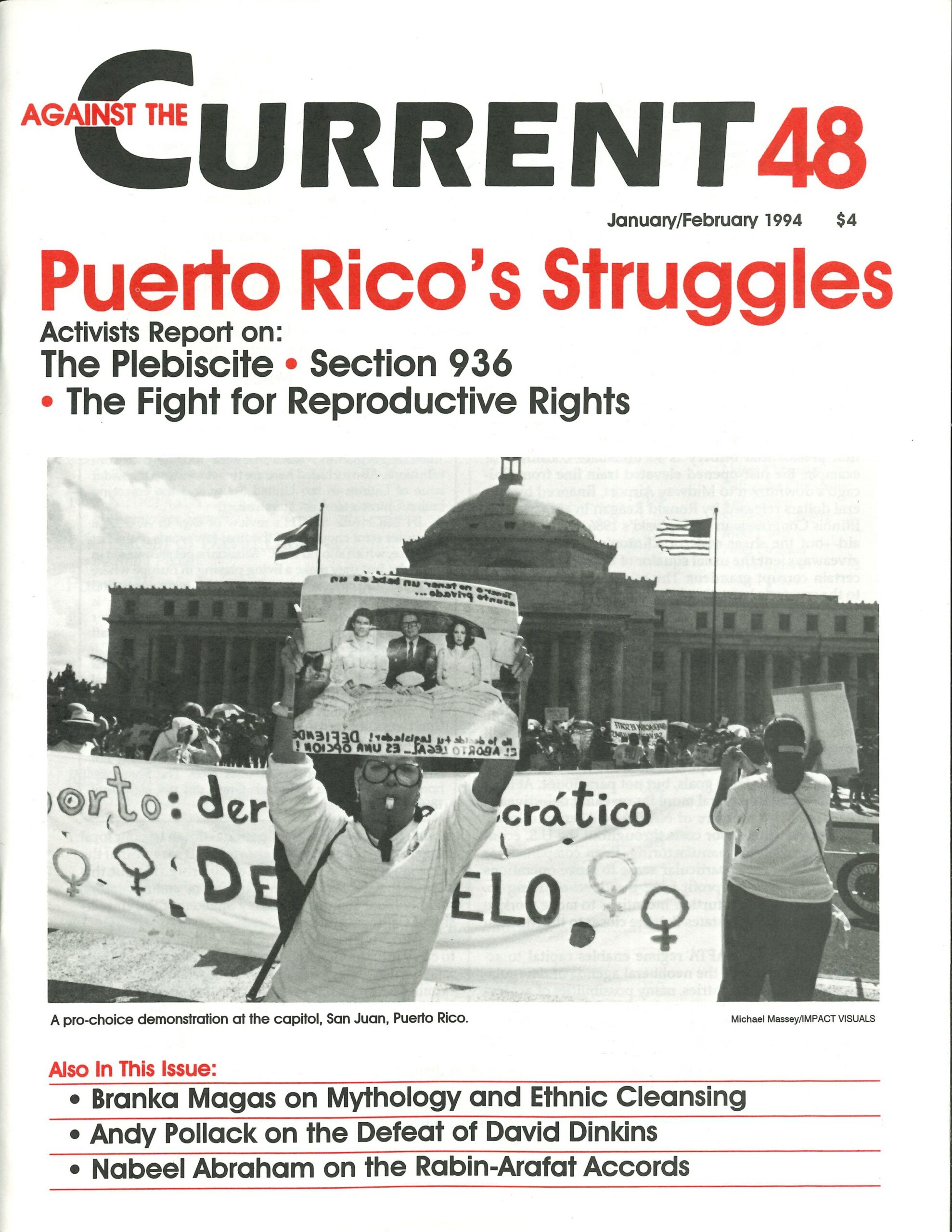

Confronting Anti-Choice Forces in Puerto Rico

— Ruth Arroyo, Rafael Bernabe and Nancy Herzig -

Al Norte

— Ruben Auger - Notes

-

Latinos: One Group or Many?

— Samuel Farber -

Latina Writers Defying Borders

— Norine Gutekanst - Reviews

-

Socialism as Self-Emancipation

— Justin Schwartz - Remembering E.P. Thompson

-

E.P. Thompson: 1924-1973

— Michael Löwy -

E.P. Thompson as Historian, Teacher and Political Activist

— Barbara Winslow

Norine Gutekanst

Woman Hollering Creek and other stories

By Sandia Cisneros

New York: Random House, 1991, $10 paperback.

Nepantli:

Essays from the Land in the Middle

By Pat Mora

Albuquerque: New Mexico Press, 1993, $18.95 hardcover.

CHICANAS—.U.S.-BORN women of Mexican ancestry—have been all but invisible in U.S. popular culture—TV, film, print media, entertainment and politics. They are, as Pat Morn calls them, “legal aliens—expected to conform to Anglo cultural norms yet subtly (and not-sosubtly) devalued for their “otherness.”

In the decade of the ‘70s African-American women writers such as Ntozake Shange, Alice Walker and Toni Morrison began to break into the literary “club” and in 1993 African-American writers, women and men, are arguably part of the mainstream U.S. literary scene.

Latina writers have been much less visible. Recent books by Chicanas such as Hoyt Street: An Autobiography by Mary Helen Ponce and So Far From God by Ana Castillo, as well as How the GarcIa Girls Lost Their Accents by Dominican-American novelist Julia Alvarez and Dreaming in Cuban by Cristina Garcia are signs that Latinas are not only finding their voices but also finding publishers.

One of these recent books is Women Hollering Creek and other stories by Sandra Cisneros. Cisneros’ book is a truly delicious collection. Her heroines are sometimes hopelessly idealistic and naive, sometimes cynical and wise, and often women who are in transit between the two. They are “women who make things happen, not women who things happen to …. Real women. … The ones I’ve known everywhere expect on TV, in books and magazines. Las girlfriends. Las comrades. Our mamas and tIas. Passionate and powerful, tender and volatile, brave. And above all, fierce.” (from “Bien Pretty”)

The title story, “Woman Hollering Creek,” tells of a young and naive Mexican woman who marries a Chicano and settles with him in Texas. They make their home along a creek called La Gritona, between her two widowed neighbors, Soledad and Dolor (solitude and pain). The woman muses over why the creek hollers. Is it out of anger? Fear? Grief? When she decides, pregnant with her second child, to leave her abusive husband, she begins to imagine that La Gritona may just be yelling for the sheer joy of being alive.

In “Little Miracles, Kept Promises,” Cisneros’ characters write letters to la Virgen de Guadalupe, El Santo Niflo de Atocha and various saints. Letters like these, often found posted in churches in Mexico, plead for a favor or give thanks for one received. A grandmother prays that the health of her tiny granddaughter suffering from cancer be restored. A man asks the Virgen to intercede to help him get the two weeks of back pay he can’t collect. A teenage girl, whose previous prayer for “a guy who would love only me” was answered, has thought better of it. She now asks, “Please, Virgencita. Lift this heavy cross from my shoulders and leave me like I was before, wind on my neck, my arms swinging free, and no one telling me howl ought to be.”

Cisneros knows exactly what her father, mother, lovers, neighbors and society in general expect her to be, and is absolutely determined to live by her own rules.

The Land in the Middle

In a different genre is Pat Mora’s Nepantla: Essays from the Land in the Middle. Like Cisneros, Morn writes to give voice to the countless “invisible” women who never see themselves reflected in the cultural life of the country of their birth. Early in her book, Mora promises musings on “economic, linguistic, and color hierarchies, about the power of naming in this country, about dominance and colonization, about unquestioned norms, about the need to create space for ourselves, individually and collectively.” Essentially, that is what she does. She draws on personal experience as well as her readings of Chicano, Latin American women and other writers.

In fact, Mora disputes the use of the term ethnic writers. She recoils at being labeled as if “some of us have ethnicity and some of us don’t … This label perpetuates the false notion that Anglo-American writers are the real writers, rather than one tradition in the evolving body of U.S. literature.” A constant theme is the fact that Anglos in U.S. society have the power to name, set the standards against which, surprise, surprise, people of color never quite measure up.

Mora examines cultural concepts of art as an example of this power to name. She questions the process by which some creative work is deemed art, while other work is considered folk art or craft work She points to how the aestheticjudgment of art is filtered through Western cultural tradition. And who are museums for anyway? Even on a free day, who feels free to come in? Can most working people visit on a “free” day, always a weekday? Do they feel comfortable there, or do they see it as a place for the rich and intellectuals? Who’s on staff in museums? How often do people of color get to decide how to present art from their traditions?

Mora further discusses the increasing commodification of artistic production and asks how many “consumers” of art would want to make a human connection with the producers of their purchases.

Born and raised in El Paso, Texas, Pat Mora has lived there most of her life. She experienced the border culture that encourages Chicanos to sublimate, repudiate and deny the Mexican part of them selves, and still never fully accepts them. She explains that she began writing children’s books to help create texts in which Chicano children could see themselves, their families and their own lives.

Mora discusses what it means to want to preserve one’s culture. She describes it as a desire to take cultural values and use them to shape a future which “subsumes our past, not denies it.” This includes reclaiming the legacy of Mexican women writers such as Cleofas Jaranillo, Fabiola Cabeza de Vaca and Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz. It includes telling stories of her mother, her aunt.

She also points out that efforts to save rain forests, endangered plants and animals are far better publicized and funded than is cultural conservation, the attempt to preserve human languages and cultural traditions that are rapidly disappearing. Ultimately Morn’s book is an open letter to Chicana writers, encouraging them to name what they see and know and feel, to “boldly infuse your work with the rhythms, images, languages that you have inherited.”

Both authors, women who occupy a space between two cultures, encourage resistance to the forced imposition of one culture upon another. They demand the right to preserve or reject any aspect of their cultural tradition as they see fit Reading Cisneros and Mora fills one with anticipation and hope that many more Chicana voices will soon be heard.

January-February 1994, ATC 48