Against the Current, No. 40, September/October 1992

-

No More Compromise!

— The Editors -

The Great Lesser-Evil Illusion

— Justin Schwartz -

Ross Perot for ...? Never Mind

— Steven Ashby -

Committee of Correspondence Looking Ahead

— Joanna Misnik -

LA After the Explosion: Rebellion and Beyond

— Joe Hicks, Antonio Villaralgosa & Angela Oh -

Gender & Re/Production in British West Indian Slave Societies, Part I

— Cecilia Green -

Greece Under the Conservatives

— James Petras and Chronis Polychroniou -

Panama: Crackdown Follows Anti-Bush Protests

— The Empowerment Project -

Israeli Elections: Who Won?

— Marcello Wechsler -

Palestine: Of War and Shadows

— Josie Wallenius -

Gender in the Revolution

— Ann Ferguson -

The Rebel Girl: The Pussy's Revenge

— Catherine Sameh -

A Brief Historical Background

— Stan Weir -

1956: The Fading Revolution

— Stan Weir -

Poverty Amidst Plenty in 1992

— Robert Hornstein and Daniel Atkins -

Oh for the Good Old Days

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

The Sixties Remembered

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Women of the Klan

— David Futrelle -

Reform and Revolution

— Samuel Farber - In Memoriam

-

Phil Clark, 1921-1992

— Patrick M. Quinn

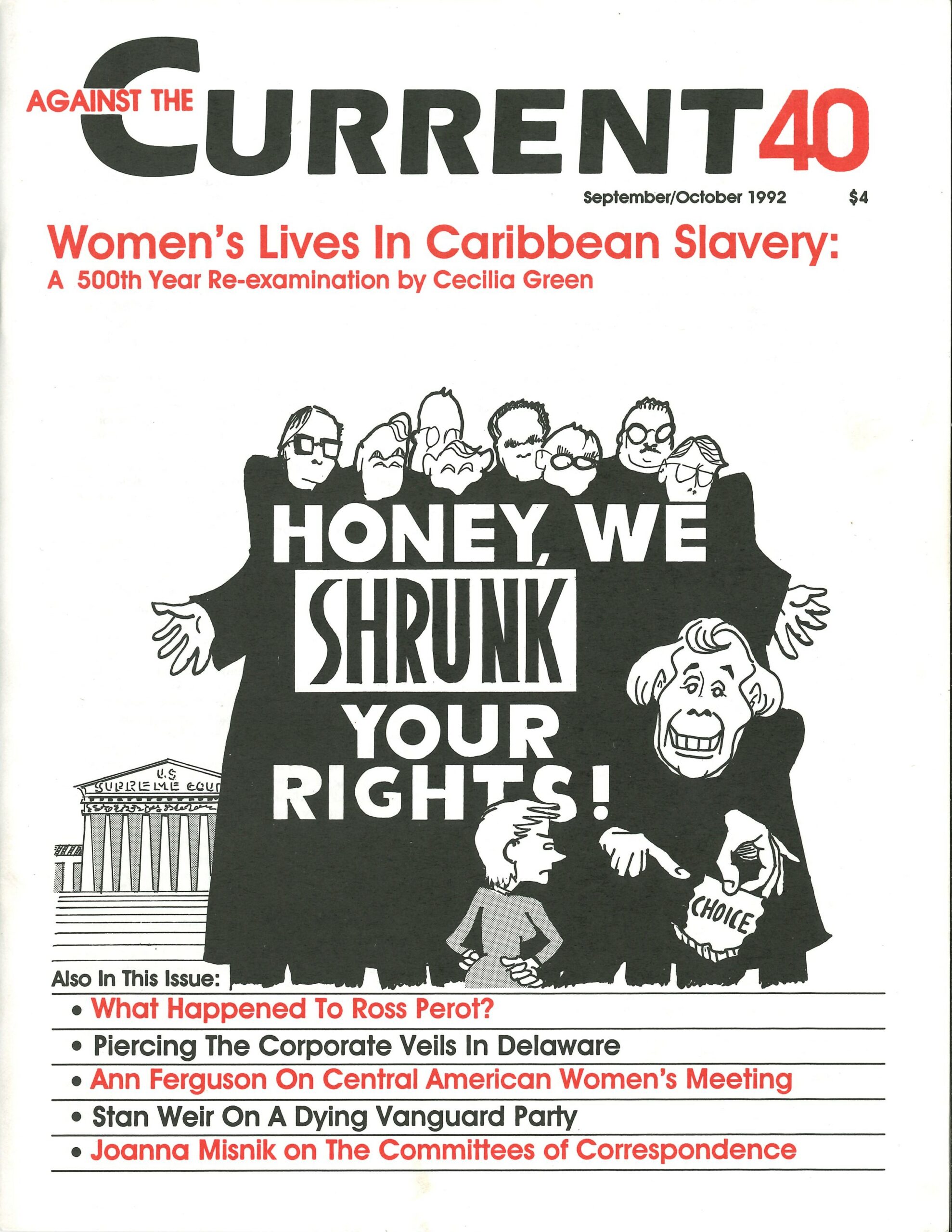

The Editors

THE SUPREME COURT RULED June 29 on the Pennsylvania Abortion Act–and both pro- and anti-choice activists, in an unusual version of the spin game, rushed to declare defeat. For the right wing, the hope had been that the Court would reverse Roe v. Wade. The decision fell short of that. The Court did uphold three provisions of the Pennsylvania law: parental consent, “informed consent” and a mandatory waiting period. A fourth provision was struck down–spousal notification–and Roe was not overturned.

While Randall Terry bitterly denounced Justice Souter on the steps of the Supreme Court, for the pro-choice movement to declare total defeat might seem puzzling. Pro-choice spokespeople seemed to agree with Chief Justice Rehnquist, who wrote: “While purporting to adhere to precedent, the joint opinion instead revises it. Roe continues to exist, but only in the way a storefront on a western movie set exists; a mere facade to give the illusion of reality.” Instead of announcing that the right to abortion had been significantly weakened but still remained legal, pro-choice spokespeople declared that the decision was tantamount to overturning Roe.

From a strictly legalistic point of view, this argument can be made. In 1973, the Roe v. Wade decision declared abortion to be a woman’s fundamental right, one that could not be restricted in the first trimester of pregnancy, and, in the second trimester, could only be regulated to safeguard the woman’s health. Only in the third trimester did the Court recognize the state’s “compelling interest” in the potential life of the fetus.

Restrictions were subjected to a standard of “strict scrutiny,” and most were initially declared unconstitutional. But that framework has been crumbling for more than a decade, as the Court began to uphold more and more restrictions. In arguing against the Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act before the Supreme Court last spring, ACLU attorney Kathryn Kolbert stated: “To adopt a lesser standard, to abandon strict scrutiny for a less protective standard, would be the same as overturning Roe.” But the Court did substitute another standard–whether a state regulation created an “undue burden” on a woman–rejecting both the previous standard and the Bush administration’s proposal. It overturned the trimester approach, while identifying three underlying principles within Roe that it affirmed: a) the right of the woman to choose abortion before viability without “undue” state interference, b) the state’s power to restrict abortion after fetal viability and c) recognition that the state has legitimate interests from the outset of pregnancy in protecting the health of the woman and the life of the fetus that may become a child.

Going into the 1991-92 session, the Court was packed with conservatives, as Clarence Thomas–the man who could say, with a straight face, that he had never discussed Roe with anyone–was confirmed. Conservatives had the votes to outlaw abortion. Indeed, in their minority decision, Justices Rehnquist, Thomas, Scalia and White called for overturning Roe outright. Yet this did not happen. Two Reagan appointees, Justices O’Connor and Kennedy, and a Bush appointee, Souter–previous critics of Roe–modified their views, and joined with Justices Blackmun and Stevens to form the majority. The three explained that the political cost of outlawing abortion is too high:

“…for two decades of economic and social developments, people have organized intimate relationships and made choices that define their views of themselves and their places in society, in reliance on the availability of abortion in the event that contraception should fail. The ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives….While the effect of reliance on Roe cannot be exactly measured, neither can the certain cost of overruling Roe for people who have ordered their thinking and living around that case be dismissed.”

They also noted this case is the sixth time in ten years that the U.S. government has asked the Court to overrule Roe. But to do so, they maintained, would be “at the cost of both profound and unnecessary damage to the Court’s legitimacy, and to the nation’s commitment to the rule of law.”

The decision is an eminently political one, openly acknowledging the justices’ fear of the social and political consequences of banning abortion. It is testimony to the impact of women’s organizing and demonstrating on public policy. Without the local organizing and the national marches in San Francisco and Washington last spring, the result would have been different. Even with a Court packed against us, the movement for reproductive freedom is not powerless.

But the decision is also an attempt to craft a compromise. And in doing so it considerably weakens a woman’s access to abortion. Interestingly enough, the decision reflects the national center-of-gravity position that has emerged out of the abortion debate: abortion should be legal, but not as readily available as it has been.

Abortion, in this view, may be necessary, but as a weighty decision deserving of a few roadblocks. It is the Solomonic middle-of-the-road “wisdom” that women should be made to suffer, but not actually enslaved–at least if they have the money, and, if teenagers, as long as their parents approve.

Public opinion polls reveal this national ambivalence. While less than 10% are for banning abortion and 30% support abortion rights, 60% waffle: supporting abortions under certain circumstances (most readily in cases of rape, incest or health of the woman), but more opposed when a woman chooses abortion for social or economic reasons (work, education), or with state funding.

Restrictions must meet the test of “undue burden.” But it is hard to imagine what burden–aside from spousal notification–this Supreme Court would consider “undue.” Overwhelming evidence was presented to the Court about the burden of parental consent, documented in states with a history of experience. Not only do laws place incredible hurdles before pregnant teenagers, but in the case of Becky Bell–who could not bear to “disappoint my parents” with the news of her pregnancy–the provision led her to an illegal abortion that resulted in her death. Yet parental consent was upheld.

Incredible Shrinking Right to Choose

When did restrictions on abortion rights begin? In 1977, during the Carter Administration, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment, which outlawed the use of federal funds for abortion. This law, to which the mainstream of the pro-choice movement responded much too feebly, was upheld a couple of years later, and the majority of states followed Washington’s lead. Increases in the number of Medicaid recipients having babies and decreases in the number having abortions have been well documented, as were the deaths of four Medicaid recipients in the last half of the 1970s from illegal abortions. Today only a dozen states and the District of Columbia fund abortions for low-income women.

Other restrictions include the 1989 Webster decision, which upheld a Missouri statute prohibiting abortions in hospitals receiving public funding even if the woman paid the full cost, and the notorious 1991 gag rule that prohibits doctors in clinics receiving federal money from mentioning abortion as an option.

Now access is affected not only for poor women (disproportionately women of color), but for middle-class women too. They are affected by waiting periods, especially if they do not live in urban centers. Their daughters are affected by parental consent legislation. They may be offended by being required to listen to a state-mandated propaganda rap. They are affected when hospitals do not perform abortions, when clinics close due to the political climate. While in 1985 nearly 25% of the nation’s obstetrics-gynecology residency programs required training in abortion procedures, by 1991 only 13% required first trimester training and only 7% for the second trimester. Currently 83% of the counties in the country–home to 31% of all U.S. women of childbearing age–do not have clinics or hospitals that perform abortions.

Current statistics indicate that 20% of the women who want abortions are unable to obtain them. More restrictions will drive this statistic higher, inevitably leading to more illegal abortions and deaths.

The struggle for abortion has been a galvanizing issue for the women’s movement, activating one generation of feminists and beginning to activate another. There is a depth to women’s commitment on this issue, powerfully demonstrated by the three enormous mobilizations in Washington and the on West Coast since the Webster debate. Although women are not likely to respond the way the Los Angeles African-American and Latino communities responded to blatant racist injustice, the Court recognized that the response to overturning Roe would be at least unpredictable. Certainly outlawing abortion would invite wholesale violation of the laws by doctors, lay providers and the women’s movement itself, which has already begun to talk about building an “underground railroad.” Previous levels of struggle might seem tame.

Neither overturning Roe nor restricting it will end the struggle over abortion and women’s bodies. Through NOW’s third party initiative the movement is beginning to speak of organizing outside the two-party political establishment.

What Next?

Four more cases are slated to be heard by the Supreme Court. Based on the current Court’s composition, the Louisiana, Utah and Guam laws, which ban abortions, should be struck down (although some restrictions may be upheld). A fourth law, which requires abortion to be a separate rider on insurance policies, that an employer must affirmatively request, is likely to be upheld.

As always in political struggles, there are two ways to look at the fight for abortion rights. One is a numbers game: How many votes on the Supreme Court? How many pro-choice Democrats in Congress? How many letters will influence this politician to vote on the issue? Are there enough votes to pass the Freedom of Choice Act or the Reproductive Health Equity Act? Accept the game and all roads lead to the Democratic Party.

It is extremely risky to entrust the future of abortion rights to the Democrats’ ability to win the presidential election. It may be even more disastrous to place confidence in their campaign promises, or to take for granted that a Freedom of Choice Act would get through the folding, spindling, mutilating and filibustering process without being filled with restrictions.

Regardless of who is elected in November, maintaining an independent mobilization for abortion rights remains vital. Preserving and extending a woman’s control over her body requires making the movement visible and articulate. It means demonstrating the depth and extent of the movement’s commitment to all women, especially those who have suffered the most under the restrictions. It means effectively reframing the abortion debate. The issue is not, “Which set of restrictions do you favor?” but, “Do you agree that women are the most appropriate custodians over their bodies.”

Among the groups based on this perspective are the Emergency Clinic Defense Committee (ECDC) in Chicago, Boston’s Reproductive Rights Network, Portland Reproductive Rights Committee, and the Committee for Reproductive Freedom (CRF) in Detroit. ECDC maintains an organized presence at clinics targeted by the right wing and is demanding that Cook County Hospital restore abortion as part of full health-care services for poor women.

CRF has made a concerted effort to build multicultural events. This past January, CRF organized a coalition for a speak-out of several generations of women on their experiences of legal and illegal abortion. It was organized with strong participation from African-American women, as well as representation from Latina and Arab women.

The period ahead will be challenging for the entire pro-choice movement, and especially so for the activist, mass action oriented wing. Public opinion polls force us to realize that the struggle is primarily educational, not electoral. In explaining why a woman’s right to control her reproductive life means enlarging a woman’s range of choices, not imposing restrictions, the movement can outline progressive solutions that sharply contrast with the anti-choice perspective.

Reproductive rights begins with sex education and health clinics in schools; comprehensive, free pre-natal and neo-natal care; adequate research and funding for better, safer contraceptives; restoration of Medicaid funding. Reproductive rights clearly opposes the state’s coercive attempts to impose sterilization or Norplant, a five-year contraceptive, on poor women and women of color. Reproductive rights opposes any attempt by the government to coerce women, including anti-gay, anti-lesbian legislation. Women need not just the legal right to abortion, but access to full health care and the right to bear and rear children in dignity. That’s the profound meaning of a woman’s right to choose.

Let the movement be united against compromise. No participation in debates about exactly which fetus pictures should be shown, how long the waiting period is, what restrictions should be included in the Freedom of Choice Act. The point is not “undue” versus “due” burdens, but basic human rights and women’s freedom.

September-October 1992, ATC 40