Against the Current, No. 37, March/April 1992

-

Democrats: Road to Nowhere

— The Editors -

Politics of Health Care Reform: Market Magic, Bad Medicine

— Colin Gordon -

Funding the Right: Rhetoric Vs. Reality in Nicaragua

— Midge Quandt -

Politicization in the Nicaraguan Schools

— Michael Friedman interviews Mario Quintana -

Carlos Menem & the Peronists: From Populism to Neoliberalism

— James Petras and Pablo Pozzi -

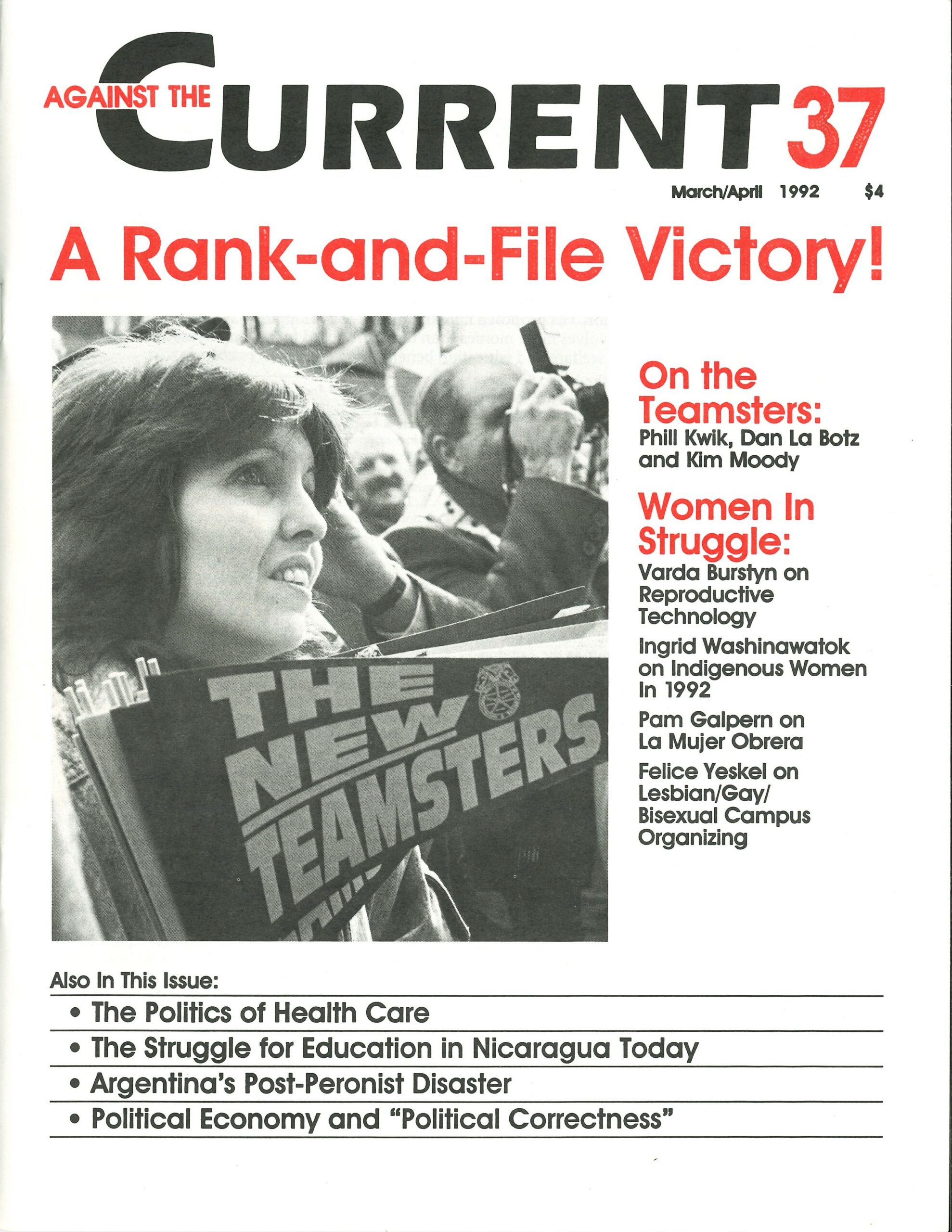

The New Teamsters

— Phil Kwik -

Rank-and-File Strategy Is Vindicated

— Dan La Botz -

Who Reformed the Teamsters?

— Kim Moody -

Political Economy and "P.C."

— Christopher Phelps - For International Women's Day

-

A Feminist Views New Reproductive Technologies

— an interview with Varda Burstyn -

Random Shots: Goodbye Old World Order

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: Implants, Identities and Death

— Catherine Sameh - For International Women's Day

-

A Notes on Reproductive Technology Terms

— Varda Burstyn -

Indigenous Women 1992

— Ingrid Washinawatok -

Latina Garment Workers Organizing on the Border

— Pam Galpern -

Campuses Out of the Closet

— Peter Drucker interview Felice Yeskel - Reviews

-

Surrealist Arsenal

— Michael Löwy -

Sisterhood and Solidarity

— Marian Swerdlow - Dialogue

-

The Rise & Fall of Soviet Democracy

— David Mandel -

On "Leninism" and Reformism

— Ernest Haberkern - Reviews

-

C.L.R. James' Collected Works

— Martin Glaberman

Marian Swerdlow

Sisterhood and Solidarity

Feminism and Labor in Modern Times

Boston: South End Press, 1987, 248 pages, $35 cloth, $9 paper.

IN THE RENEWAL of the pro-choice movement, class-conscious feminists have been concerned with the disproportionately small numbers of working-class women, including women of color, among its leaders and activists. There has been discussion of possible explanations and solutions for this isolation and the limitations it imposes on the movement.

Diane Balser’s recent book, Sisterhood and Solidarity: Feminism and Labor in Modern Times, sheds important light on these questions through its examination of three historical attempts by women to organize themselves as women and as workers at the same time. For today’s organizers, this book offers insights into the conditions under which working women’s organizations arise, the reasons they grow and win victories, and the problems that limit and weaken them.

Balser’s first case study is the quite short-lived Working Women’s Association of 1868. The Working Women’s Association saw its brief heyday during the few years of labor movement strength between the Civil War and the onset of crisis in 1873. (One of Balser’s minor shortcomings is she doesn’t place her cases in the context of the contemporary state of either the labor movement or the economy.)

Working Women’s Association allied with the National Labor Union and carried out some successful organizing among women printers. It faltered quickly when Susan B. Anthony and its other feminist leaders, disillusioned by the obduracy of male trade union leaders, turned to employers for help.

Baker’s discussion unfortunately views the organization’s disappearance solely in the context of a discussion of the question of possible intrinsic contradiction between feminism and labor unionism and the beliefs of its leaders.

Baker is interested mainly in ideological and programmatic questions, so she overlooks structural causes for the disappearance of this group. In the 1860s, women workers fell far short of the numbers and strength which would have enabled them to wage a palpable struggle for equality within the trade union movement.

The Rise and Fall of Union WAGE

Union WAGE (Union Women’s Alliance to Gain Equality) was founded one hundred years later, and has far more relevance for today’s organizers. Its founders were conscious leftists. They were responding to what they perceived as the neglect shown to working women, the workplace and union issues by the mainstream women’s movement Balser describes the women who founded it as:

“sixteen women who shared a common political perspective on the question of class, gender and working women… .Many had been (and some still were) members of Old Left political parties such as the International Socialists, Socialist Workers Party and the Communist Party.”

Union WAGE thus was founded in the vigorous youth of feminism’s “second wave.” Although Balser fails to point it out, it was also the early days of a rank-and-file upsurge that swept the trade unions. Union WAGE’s birthplace was the San Francisco Bay Area and this remained its only significant base.

Despite beginning as an organization of union members, Union WAGE was never exclusionary in its membership. By 1974, it spelled out in its constitution that it admitted “all working women” whether or not they currently held jobs or belonged to unions. Just a few years later, the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW) was to steal its thunder as the union women’s organization. However, CLUW never approached Union WAGE’s scope of independence from the top labor brass, nor its depth of class consciousness.

Near the close of its single decade of existence, Union WAGE was shaken by caustic internal disputes. Baker devotes to this an amount of detail that seems unnecessary, since Union WAGE had already experienced considerable decline. An acquaintance with the political events of that period leads to the belief that its downfall was part of the ebb of the two movements whose cresting gave it life.

Union WAGE’s newspaper (of the same name) seems to have been an important link and forum for activists. In its pages, beside news of union and workplace struggles, such issues as the relationship between feminism and unionism, dual unionism, the analysis of trade union leadership and the politics of CLUW were thrashed out These same issues were the focus of Union WAGE’s meetings, conventions and conferences.

It is unfortunate that Balser cites no figures for membership, meeting attendance or newspaper circulation. Such information would permit a much better assessment of the organization’s strength and influence. Without it, it is difficult to draw any conclusions about its success in reaching working women.

Organizing the Unorganized

Union WAGE apparently did reach large numbers of working women when it encouraged the organization of the unorganized. Its conference on this theme in November 1975 drew 500 people from all over the West Coast But, Balser notes, “WAGE … became a resource center that offered appropriate help, rather than a place where much organizing was initiated.”

Why was this the case? Certainly WAGE’s founders, and most of its leaders, understood the centrality of organizing the unorganized. It was high on the list of organizational purposes given in its first newsletter, and appeared second in the 1974 statement of purpose and goals. In the light of this, it is striking that the 1975 conference had no sequel and Balser mentions no initiation of organizing drives whatsoever.

Balser herself emphasizes that organizing unorganized women is the key to the progress and the power of both the labor movement and the women’s movement First in her introduction, and later in her conclusion, she argues that to win the political demands of feminism, women need the power derived from workplace organization.

Despite this view, she gives very little information on WAGE support for unionization drives and devotes little discussion to the question of why WAGE confined itself to support She relies on the explanation that, beginning in 1973, Union WAGE leaders had bad experiences with trusteeships and with a jurisdictional dispute. These problems, she claims, divided them as to whether to organize women into existing unions or to found new unions. This indecision Balser blames for Union WAGE’s lack of leadership in organizing.

However, Balser’s overall description presents a clear picture of the WAGE leadership united in firm opposition to dual unionism. This undercuts the persuasiveness of her explanation. Her reasoning also fails to explain the lack of initiative in WAGE’s first couple of years.

Balser additionally puts the blame on Union WAGE’s failure to deal with the gender aspect of women’s double oppression in practice. While organizing within the wage work force, they did not include such gender related demands as daycare, maternity benefits, reproductive freedom and such.

This criticism has tobe taken on faith, since Baker never describes any of Union WAGE’s workplace organizing. Since Union WAGE’s own founding statement includes paid maternity leaves and childcare facilities, and added flee abortion on demand in 1974, Balser should provide evidence for her assertion.

The same social movements that produced Union WAGE also brought forth the Coalition of Labor Union Women in 1974. By this time the women’s move ment had become more popular and was developing a “respectable” reformist wing. CLUW, like Union WAGE, had trade union officials as founders. These, however, were international union officers, perched far higher on the bureaucracy totem poles.

The founders of Union WAGE had been trailblazers. Following in their footsteps after three years of similar initiatives, CLUW’s more cautious founders felt both the pressure of the growth of the women’s movement and the reassurance of its increasing respectability.

CLUW’s first year was marked by struggle over its political character between forces committed to the AFL-CIO leadership, and those who sought to give the new organization a more independent and radical direction. When the dust settled, the conservatives had the clear upper hand, and the losers were effectively shut out of the organization.

CLUW’s Limitations

In the struggle to force organized labor to address the needs of working women, Balser feels CLUW has made “only a beginning.” What has limited CLUW more than anything else, she feels, is its own lack of ability to “unionize the majority of still unorganized women.”

Certainly, CLUW recognizes the importance of this goal and places it prominently in its statement of purpose. Why has CLUW, a national organization with far greater membership and resources than Union WAGE, still been ineffectual in this regard?

Balser offers the explanation that CLUW is not a union and therefore cannot unionize directly. More important is its unwillingness to “side with one union over another.”

In viewing the problem this way, Balser implicitly adopts the perspective of CLUW’s leaders, that is, the perspective of top level union bureaucrats. For men or women in such positions, unionization campaigns are run not in cooperation with other internationals, but in competition.

Organizing new workers is often a source of strain between unions. So itwill be a pretty unpopular activity in an organizational leadership made up of officers of different unions who are trying to work together.

The state’s policy of confining workers in this country to a “sole bargaining agent” and the lack of politically unified labor federations sets the stage for fratricidal conflicts among United States unions for new membership, regardless of the good intentions of individual union officers In CLUW, these conditions stand in the way of initiating campaigns in which workers themselves decide into which union they wish to organize.

For many years CLUW further removed itself from opportunities for organizing the unorganized by excluding them from membership. CLUW repeatedly and expressly refused to admit unaffiliated women, because in the words of one leader, such admission would open up the risk of “weakening its specific union orientation.”

It is certainly desirable to maintain this orientation by encouraging union members to join CLUW. However, CLUW’s leadership refused to admit even women active in unionization drives, including those who had gone as far as signing authorization cards! On the past few years, associate memberships have become available to women wishing to join who aren’t union members.)

Balser concludes that a working women’s organization that is defined by the existing labor hierarchy, the way CLUW is, will never be able to make the full gains possible for working women:

“My analysis suggests that the existence of an active <i>independent</i>movement promoting the interest of working women is equally necessary [emphasis in original].

Lessons for Today’s Organizers

With the resurgence of the women’s movement, sparked by the issue of the right to abortion, the time seems ripe for renewed initiatives for an independent working women’s organization, along the lines of Union WAGE.

Union WAGE was the brainchild of class-conscious women in the union movement, and it is logical that the same sort of women must kick off today’s efforts. Such initiatives will succeed best if they are broad and non-sectarian, like Union WAGE.

If Balser has one outstanding point to make for today’s class-conscious feminists, it is that the central task for advancing both the women’s movement and the labor movement is the unionization of unorganized women. Her book tells us that offering encouragement and resources is not enough.

It is necessary to lay out strategy and to take initiatives. To do this, today’s organizers must work with organized labor. But the history Balser presents makes it clear that to be effective, their first allegiance must belong not to any specific labor institution, but to rankand-file working women, and to the building of their movement.

March-April 1992, ATC 37