Against the Current, No. 37, March/April 1992

-

Democrats: Road to Nowhere

— The Editors -

Politics of Health Care Reform: Market Magic, Bad Medicine

— Colin Gordon -

Funding the Right: Rhetoric Vs. Reality in Nicaragua

— Midge Quandt -

Politicization in the Nicaraguan Schools

— Michael Friedman interviews Mario Quintana -

Carlos Menem & the Peronists: From Populism to Neoliberalism

— James Petras and Pablo Pozzi -

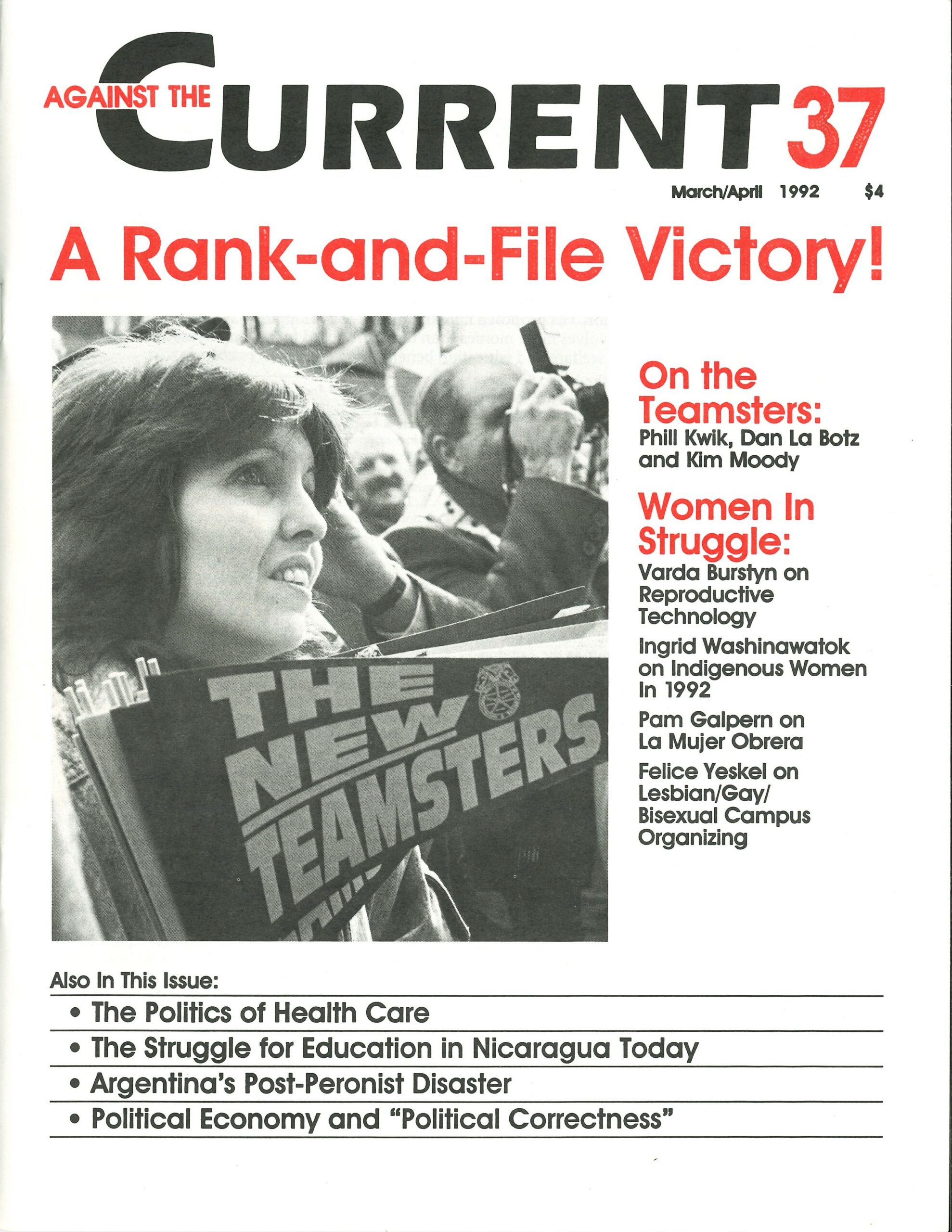

The New Teamsters

— Phil Kwik -

Rank-and-File Strategy Is Vindicated

— Dan La Botz -

Who Reformed the Teamsters?

— Kim Moody -

Political Economy and "P.C."

— Christopher Phelps - For International Women's Day

-

A Feminist Views New Reproductive Technologies

— an interview with Varda Burstyn -

Random Shots: Goodbye Old World Order

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: Implants, Identities and Death

— Catherine Sameh - For International Women's Day

-

A Notes on Reproductive Technology Terms

— Varda Burstyn -

Indigenous Women 1992

— Ingrid Washinawatok -

Latina Garment Workers Organizing on the Border

— Pam Galpern -

Campuses Out of the Closet

— Peter Drucker interview Felice Yeskel - Reviews

-

Surrealist Arsenal

— Michael Löwy -

Sisterhood and Solidarity

— Marian Swerdlow - Dialogue

-

The Rise & Fall of Soviet Democracy

— David Mandel -

On "Leninism" and Reformism

— Ernest Haberkern - Reviews

-

C.L.R. James' Collected Works

— Martin Glaberman

Dan La Botz

THE ELECTION OF Ron Carey to the office of General President of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IB1) with the support of Teamsters for a Democratic Union (FDU) is not only a victory for the Teamster reform movement, but also for a particular strategy for reform and revitalization of the labor movement the rank-and-file stratey.

At this point it is only a qualified vindication, in the sense that it remains to be seen what Carey and there-form forces in the Teamsters will accomplish in the next few years. Yet the mere election of Carey, ending decades of Mafia control, is a remarkable achievement that holds hope of reform not only in the Teamsters, but in the labor movement and in society. That achievement was in large measure a result of fifteen years of hard work by TDU.

As an editorial in the Nation observed, “Change would not have come so swiftly without government intervention, but neither would Carey now be president without Teamsters for a Democratic Union, the insurgent caucus that insisted the government authorize direct election of the union’s leaders instead of a plan for federal trusteeship. As a movement, the TDU has labored to define the content of union democracy—informing workers about shrouded contract negotiations, exposing corruption, securing worker rights, creating a vehicle for ideas and ultimately forming the organizational spine of Carey’s campaign.”

Flashback—A Debate Over Social Change

At the heart of TDU’s work has been a rank-and-file strategy, an approach and method that distinguish TDU from several other attempts at union reform. At this moment of victory for reform forces in the Teamsters, we should look back to consider the significance and the lessons of the rank-and-file strategy.

During the 1960s, in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement and the student movement, a debate raged among political people over the question of how to bring about progressive social change Where should they be active in order to further progressive social change? What social groups were likely to be the agents of new social developments?

In those years liberals like John Kenneth Galbraith wrote that America was The Affluent Society, in which he pictured the United States as a nation that had virtually conquered poverty and need, and had only to wrestle with the problems of consumerism and leisure time. At the same time Daniel Bell’s End of Ideology argued that in this affluent America,political ideology and social radicalism had come to a dead end.

Even on the left, the radical Herbert Marcuse believed that affluence and the end of ideology had created the One-Dimensional Man. By one-dimensional Marcuse meant that the affluent, non-ideological society was able through cooptation to contain its traditional—especially class—contradictions. From the point of view of those authors, one widely shared among middle-class intellectuals at the time, working-class people were largely “bought off.”

Workers, it was widely believed, at least white workers who had homes, cars and televisions, would not become involved in progressive causes or social movements or even in their own unions. They were the blue-collar reactionaries who supported the war in Vietnam, the construction hardhats whom Nixon called upon to attack antiwar demonstrators. From this perspective no union better exemplified the character of the American working class and labor unions than the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the Mafia-dominated organization that endorsed Nixon for president.

A Working-Class Orientation

This widely accepted analysis of American society tended to shape the debate about the prospects for the future among young radicals in the 1960s. As young radicals in groups like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) debated how to overcome war and racism and bring about a better society, various currents proposed different strategies. Today these debates seem rather strange but at the time they were taken quite seriously.

Some activists called for a turn to the most poverty-stricken, or to semicriminal elements of society, who seemed to be the only group outside the affluent society. Others argued for armed revolution by small groups of guerrilla warriors or terrorists, and ended up in factions like the SDS “Weathermen? Still others called for the creation of a Stalinist/Maoist party to lead a “peoples’ revolution.” But by the late-‘70s these strategies, and the activists who pursued them, had exhausted themselves.

Still other socialist-activists argued that political people should have an orientation to the working class, support organizing drives and strikes like those of the United Farm Workers, and become involved in labor unions. America, they argued, was not really an affluent society, at least not for most working-class people.

If a few workers were affluent, most lived from pay check to pay check, and at work found themselves locked in struggle with the employer over wages, benefits and working conditions. Moreover it was workers and their children who were giving their lives in the Vietnam War and paying for it with their taxes.

These socialists pointed out that capitalism was reentering a period of economic crisis, and American capitalism, however successful it appeared at the moment, could not contain social change. The conflicts between the corporations and the country’s working people would not be permanently coopted and contained, but would inevitably break out in new social struggles.

Given the size of the American working class, avast majority of some 100 million wage-earners, and their key economic role as producers of the nation’s wealth, once the working class moved it would be capable not only of changing its own labor unions, but of reshaping all of American society. So some young people of the generation of the 1960s and ’70s were convinced that the most meaningful way to change American society would be to become active in the labor movement. But where to go and what to do?

Strategic Debates and Options

There were a variety of radical strategies for involvement and activism in the labor movement One, associated with some of the widespread post-1960s local political collectives, might be called “with the most oppressed.” A second, whose slogan might be “officials and technicians in the lead,” can best be described as a strategy of permeating the existing labor leadership. This approach had political roots both in the early (roughly pre-1966) SDS and in the traditional social-democratic politics that came to be embodied in Michael Harrington s Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee and currently Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). A similar strategy informed much of the practice of the Communist Party.

Still a third perspective was that of various radicals whose slogan might be put, “for rank-and-file rebellion in the unions.”

The radical political collectives, whose full history remains to be written, often took jobs in small often nonunion shops, and concentrated on organizing the workers either into a labor union or sometimes into their collective. There were successes; some shops were organized, some contracts won and some workers became more active both in their workplace and in politics.

Yet by and large the strategy of going to the most oppressed was a failure in that it had little significant impact either on the working class or on American society as a whole. The problem with this approach was that it saw the worker as victim. Strategically, it mistakenly chose the most victimized who were also often the weakest organizationally. Further, the dispersed character of the local political collectives gave them no way to coordinate and link worker struggles.

In general, the history of labor movement organizing is based on power and success. Successful organizing moves from strength to strength, and from success to success. If low-paid small shop workers were to be organized, it would probably have to be as an entire community or population or in association with some other more economically and politically powerful groups of workers, but not isolated political collectives.

Contradictions of Permeationism

The second radical strategy in the labor movement did focus on power—the power of the labor officials. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s a number of people were attracted to the group in the Socialist Party and later DSOC led by Michael Harrington, while others from the New Left became involved in the New American Movement; eventually those groups merged to form DSA.

This current saw the American labor movement as having conservative and progressive wings. The conservatives, led by George Meany and made up of the old American Federation of Labor unions, particularly the building trades, were racist and hawkish and generally politically conservative. The progressives were led by Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers (UAW), but also included others such as the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees led by Jerry Wurf, and the International Association of Machinists led by William Wmpisinget (Wurf and Wmpisinger were at least nominally members of DSA.)

In this view the progressive unions’ officials and staff technicians were usually politically in advance of their membership. The membership was unfortunately mired in the day-to-day struggle for existence, while labor union officials and technicians were engaged in the important work of union organizing and servicing the union’s membership, as well as in real politics—the attempt to elect more liberal Democrats to office.

Thus it made sense as political strategy to work, for example, in union research and education departments, as organizers and business agents, or as individuals to get elected to union office with the existing “progressive” slate. With more socialists in the union leadership it would be possible to help turn the unions in a more radical direction. Over time, it was believed, socialists who worked for the union would come to influence both the officials with whom they dealt down at the hall, and the rank and file whom they serviced as union reps. The strategy, in short, was basically that the socialists would permeate the labor movement.

The UAW is perhaps the best example of what this meant in practice because it was always DSA leader Michael Harrington’s example. The UAW had, in the 1960s, the reputation as the most liberal and progressive union in the United States. Walter Reuther supported both Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers Union, and Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. A few UAW leaders like Region 6 Director Paul Schrade opposed the Vietnam War, and the UAW as a whole was never as enthusiastic about the war as the old AFL unions and the building trades.

But those who went into UAW structures as ardent socialists dedicated to uplifting their colleagues and the workers they served were sorely disappointed. The UAW resisted the Black Power upsurge in the auto plants in the late 1960s and early 70s; broke unofficial strikes against speedup and unbearable heat; negotiated concession contracts in 1979; and entered into partnership with the Chrysler corporation in 1982.

After Leonard Woodcock and Doug Fraser, the union in the hands of Owen Bieber and the Administration Caucus became a tool for suppressing dissenting union officials and reform movements like Jerry Tucker and the New Directions Movement So what had gone wrong with the strategy?

First, the social democratic perspective failed to grasp (or, where it did, failed to draw the conclusions from the fact) that the labor union officialdom, better called the labor bureaucracy, was a group within the union and a sort of social caste with its own economic interests separate from those of the workers it represented. Union officials usually received much higher salaries (though less so in the UAW), expense accounts and perquisites like union cars.

Perhaps most important, the union officials had clean fingernails. They did not work in the plant or office, did not share the work and life experience of the union’s members. At the highest levels, union officials hobnobbed with corporation executives, Democratic Party big-wigs and government bureaucrats. Some individuals may be capable of resisting the lure of lifestyle and the enticement of salaries, expense accounts and the “perks” of office, but an entire group cannot resist such pressure over years and even decades.

The union bureaucracy’s central goal is often simply to establish relatively stable and harmonious relations with the employer. Again, to take Reuther as an example, over the years between 1947 and 1970 Reuther succeeded in winning higher wages and better benefits for the UAW members, but by the mid-1950s Reuther never seriously dealt with the issue of working conditions and speedup, and in fact gave up on those issues altogether, even though they were among the most important concerns of the union’s members.

When push comes to shove, for whatever reason, there are union leaders who will throw in their lot with the rank and file. But whatever its political ideology, by and large and taken as a whole, the union bureaucracy is a conservative caste protecting its own interests.

It is usually the corporation management that decides either to attempt to destroy the union officials and their union or to stabilize them in power, by working with the union leaders to create legal and contractual restraints on the union members. At that point the union officials become junior partners in the management of the corporation, with the job of policing the workplace against disruption.

For instance, after the tumultuous period of the UAW from the sitdowns of 1936 to the strike of 1946, General Motors and the other major automotive manufacturers decided to stabilize and to support Reuther as the best of alternatives presented them. They signed the 1948 GM contract and then the “Treaty of Detroit” in 1950, a five-year contract with the major manufacturers. That was followed by the three-year agreements with ritual negotiations, and basically by labor peace.

The permeationist perspective also failed to appreciate the pressures exerted by the union bureaucracy on activists who took positions in the union as organizers or technicians. Union officials were politically shrewd and not easily influenced; the bureaucracy had its own caste culture and values that it attempted to impress upon its staff. The union hail was still often far from the workplace, if not geographically, then spiritually.

The union bureaucracy expected its technicians and organizers to carry out its directives—to control the membership, or to mobilize it within very strict limits. Down at the hail, they didn’t want any troublemakers. More often than not the individual official or technician tended to become not corrupt, but cynical. (Eventually with relatively large numbers of union staff members among its members, the DSA itself tended to become, at least in part, an organization which expressed the interests of the union bureaucracy, and always constrained by the bureaucracy’s politics.)

The Rank-and-File Strategy

The rank-and-file strategy was adopted by various political groups and individuals throughout the labor movement from the 1960s to the 1990s, with varying degrees of success depending upon the circumstances. Rank-and-file strategists were involved in the Miners For Democracy movement within the United Mine Workers. Others were involved in the Ed Sadlowski campaign for president of the United Steel Workers of America, the Dave Selden opposition in the American Federation of Teachers, the United National Caucus in the United Auto Workers Union, and in reform movements in the Teamsters such as Teamsters United Rank and File and Teamsters for a Democratic Union, and in other rank-and-file groups.

The rank-and-file strategy may never have existed on paper as a fully worked out plan, but its essential ideas can be seen in the practice of those who were involved in rank-and-file movements over the years. These activists were far from being part of any single political tendency, however, among the organized groups, the rank-and-file strategy was most consistently articulated and energetically practiced by the International Socialists of the 1970s.

First, the rank-and-file strategy argued that it was workers in key economic sectors who had the power to reorganize themselves and then to help to organize others. At the time of the 1960s and ’70s those sectors were industries like mining, steel, auto, trucking, telephone, and services like the postal service, teaching and big city public employees. Workers were more likely to organize and fightback, the argument went; where they had some real economic or political power.

Second, the rank-and-file strategy proposed that radical activists would be most effective working with labor unions, rather than expending their energies at first in organizing the unorganized. Certainly there was a need to organize the unorganized, but successful organizing campaigns required militant unions with the power and determination to carry out such a campaign—so it would be necessary to reform the unions.

Third, the strategy suggested that there were certain cities, plants and local unions where workers were likely to first become active because there were large units with many workers and there was a history and tradition of struggle Moreover, the strategy emphasized neither the workers’ poverty and oppression nor the union’s ideology or progressive character, but rather the potential economic power and potential for struggle of the rank and file.

The rank-and-file strategy began with an analysis of the labor movement which was in certain respects almost the mirror opposite of that of the permeationists. The strategy argued that ordinary workers and union members, whatever their political ideology, tended by virtue of their place in the productive process and in society to be potentially more radical than the union leaders. Put simply and crudely, better to be with a group of rank-and- ifie workers who considered themselves to be Republicans than to be with a group of union officials who considered themselves to be Democrats or even socialists, because the rank-and-file workers would be driven by the circumstances to struggle against the system, while the union officials would tend to seek the comfort zone.

The rank-and-file strategy argued that the workers’ real life experience could lead to change in the workers’ views and opinions. Organization could not be created from outside; rather, its viability depended on meshing with already existing insurgent impulses at the workplace level (around speedup, conditions, racist or sexist harassment, etc). Reality was pretty radical and would tend to radicalize the workers. The strategy was linked to an analysis of the economy which explained that the long post-World War 11 prosperity of capitalism had ended sometime in the late 1960s or early 1970s, and that an economic crisis would drive the employers to attack the labor unions and workers’ standard of living.

The employers’ offensive would cause a political crisis in the unions because the labor union officials, even the so-called “progressive” officials, were not prepared or capable of organizing the defense of workers’ interests. The vacuum of leadership would make it necessary for rank-and-file workers to create their own alternative leadership which would put forth a new program for the unions. At the center of that program would be a struggle for union democracy, for no matter whether the union was conservative or “progressive,” the union leaders resisted all initiative from the rank and file which tended to rock the bureaucratic boat.

The Rank-and-File Strategy and TDU

The struggle for a democratic union was linked to the struggle for a more militant union which could defend the contracts and begin to engage in new organizing It was a union-as-crusade, not union-as-insurance company model: Rank-and-file workers would have to rebuild their union themselves, starting out on the ground floor. The rank-and-file movement was the reborn union in embryo within the shell of the old bureaucratic structure. Rank-and-file activists were part of a movement within their workplace and local unions.

The union was not about service so much as rankand-file power, the power to make decisions which would better all of our lives. The union would be changed by activists who were willing to provide an example of leadership, courage and principle: not a group of radicals who took heroic individual radical actions, but ordinary workers who did such simple things as hand out leaflets to their fellow workers advocating a better contract An activist minority would be able to galvanize larger numbers, and eventually be able to win the support of the majority of the union’s members in a movement for reform.*

Teamsters for a Democratic Union is perhaps the best example of the rank-and-file strategy for union reform, a phenomenon due in part to the peculiar characteristics of the Teamsters union. During the 1950s and early ’60s, Teamster General President Jimmy Hoffa had centralized the union bureaucracy and collective bargaining in the hands of the president and executive board and entered into deals with the Mafia.

When Hoffa went to jail in 1%7, Frank Fitzsimmons and the other Mafia-dominated leaden of the union became the captives of Richard Nixon and the Republican Party. The Nixon administration would not prosecute the Mafia-connected union officials if they would support Nixon through the Watergate scandal. The Teamsters union had only one old socialist leader on the executive board, Harold Gibbons of St. Louis. Gibbons who ran a social-democratic-style local union at home, acted as the house intellectual for Hoffa and his Mafia cronies, and found solace in various private vices. Such a union was not very amenable to the permeationist strategy; the Mafia has its own technicians.

The 1970 wildcat strike had led to the creation of a national rank-and-file opposition known at Teamsters United Rank and File (TURF) in which a few young radicals had participated. After the break-up of TURF, some former TURF members and other local union’s activists came together in 1976 to form Teamsters for a Decent Contract, and out of that contract campaign came TDU.

>p>The TDU activists were mainly freight workers (truck drivers, dock workers, clerks), grocery warehouse workers, car haulers and UPS members. TDU was based mainly in big-city freight locals such as Los Angeles Local 208 and Cleveland Local 407, the political heart of the Teamsters union. Some young political activists with experience in the civil rights, antiwar and student movements got jobs in the trucking industry, became Teamsters, and helped to cohere U. They brought to the movement their organizing skills, their social idealism and, perhaps most important, a national perspective and strategy which helped to link up local Teamster struggles.

But mostly TDU was always an organization of ordinary Teamster union members. Most TDU members were Democrats and Republicans, Catholics and Baptists, not radicals. Several TDU activists in the South, for example, were African-American fundamentalist preachers. TDU was never organized on an ideological basis, but was radical only in the sense that it was a movement for union democracy, in a union that was a dictatorship, and advocated decent contracts when the leaden negotiated sweethearts.

Initially TDU had the character of a wildcat strike movement, and TDU activists led wildcat strikes of freight workers, UPS workers, carhaulers and steel-haulers. But after 1979, with the deepening economic crisis, workers became more cautious. TDU still recommended no votes on contracts, but few workers were willing to fiht the company and their own union officials with wildcats.

From the very beginning TDU had operated on several levels. It had engaged both in contract cam-pains and strikes, but also in 10 national union conventions. Merger with the somewhat more moderate Professional Drivers Council (PROD) also gave TDU an experienced legislative and lobbying organization. TDU was involved in every sort of activity, from helping workers to fight grievances to testifying before Congress. As it grew TDU reached out to work with Teamsters in the canning and frozen food plants in California, in the construction industry in British Columbia and the Yukon, in the brewery industry and in the Teamster locals in Puerto Rico. Almost all of this activity was squarely in opposition to the Mafia-controlled Teamster union officials at the International level, and to most local officials.

In the course of this organizing work over fifteen years TDU grew to a size of about 10,000 union activists, but, more importantly, TDU could mobilize many more members in campaigns and in votes against the Teamster leaders’ sweetheart contracts. TDU members ran for local union office throughout the United States and Canada, winning office in cities such as Denver and Atlanta. Where independent-minded local officials appeared who were willing to stand up, speak out and organize, TDU joined with them. In that way officials such as Jack Vlahovic of Local 213 in British Columbia, Sam Theodus of Local 407 in Cleveland and Ron Carey of Local 804 in New York joined in coalitions with TDU.

Some like Vlahovic actually joined TDU, others like Carey declined the opportunity, but cooperated on contract campaigns. In 1986 TDU endorsed Sam Theodus, the President of Teamster Local 407 in Cleveland, as its candidate to oppose Teamster General President Jackie Presser Similarly, in November 1989, MU decided to endorse Ron Carey’s bid for the Teamster presidency.

The Carey Campaign

The rank-and-file strategy recognized that as power built up in the rank and ifie and as tensions built in the union, there would be a split within the union along a ragged, diagonal line with a small number of officials from the leadership being drawn toward the Power of the rank and file. As the union was gradually ripped apart by the issue of the RICO suit (see accompanying article by Kim Moody), a number of officials were genuine converts to the movement Big crises and big movements can change people in big ways.

Clearly there was no possibility that TDU could endorse either the reactionary Walter Shea slate or lesser evil—but also compromised—R.V. Durham slates, since both Shea and Durham had been part of the old leadership. The question in the case of Carey was whether there was the basis for an alliance, and whether TDU could maintain its identity and carry on its work.

In fact both were possible: Both Carey and TDU had opposed concessionary national contracts.

Al the same time, there was nothing about Carey’s campaign that required TDU to dampen its ardor in demanding decent contracts and opposing the International. Carey’s Local 804 was a democratic local union with a militant tradition. And Carey’s campaign was strongly influenced by TDU’s organization and ideas. Most important, a Carey victory would end the Mafia stranglehold on the union, break its bureaucratic death grip, free up the Joint Councils and local unions and give rank-and-file activists more political space.

During the course of the campaign, one particularly interesting episode revealed the differences between the permeationist and rank-and-file strategies. One member of the R.V. Durham slate was Dan Kane, a President of IBT Local 111 in New York, who joined trade union coalitions in support of El Salvador and spoke up for Jesse Jackson. Kane and Durham attacked Carey as a registered Republican.

A number of radicals in New York supported Kane and Durham, on the grounds that Kane was a progressive union official—luckily the union’s rank and file have better political instincts than many leftists! Carey was prepared to mobilize the members of his own union in a fight for their interests in a way that Kane and Durham would not And Carey was prepared to work with TDU and the more militant reformers, while Durham—and Kane—represented the continuity of the hierarchy.

A Victory and a Turning Point

Carey and the reformers are themselves now top union leaders, and all of the conservatizing and bureaucratic tendencies emanating from the very nature of the union and from the pressures of the employers will work on them as they once worked on their opponents. Those tendencies can be resisted by turning the entire Teamsters union into a crusade, a revival and a social movement.

It may be hoped that the Carey victory will have some impact not only on the Teamsters and on other unions, but also on young people outside the labor movement, on those who want to see progressive change in our society. Perhaps the Carey victory will lead them to chose to work in the labor movement And if so, they should chose to become organizers of a rank-and-file rebellion in the unions, to overturn the existing bureaucracies and bring the ranks to power.

*This was in part a revival of the ideas of such forces as the Minority Movement In Britain and the Trade Union Education League in the United States during the 19s. In general, the rank-and-file strategy suggested that young people should find the older rank-and-file activists who had been involved in the union for years and learn from them the history, traditions and culture of the industry and union. The strategy appreciated that working-class people have their own valuable experiences, values, ideas and informal organization& Young political people had important ideals and skills to bring to the union movement, but only if they understood how to work those skills and ideals into the existing working-class culture and organization.

March-April 1992, ATC 37