Against the Current, No. 36, January/February 1992

-

1992: Seize the Time!

— The Editors -

Old Nazi in a New Suit

— Scott McLemee -

The Future of Reproductive Freedom

— Angela Hubler -

Women Under Chamorro's Regime

— Barbara Seitz -

Rebel Girl: Women, Sex and Disease--II

— Catherine Sameh - End the Blockade of Cuba!

-

Cornucopia Isn't Consumerism

— Jesse Lemisch and Naomi Weisstein -

Random Shots: Thoughts on Rivethead

— R.F. Kampfer -

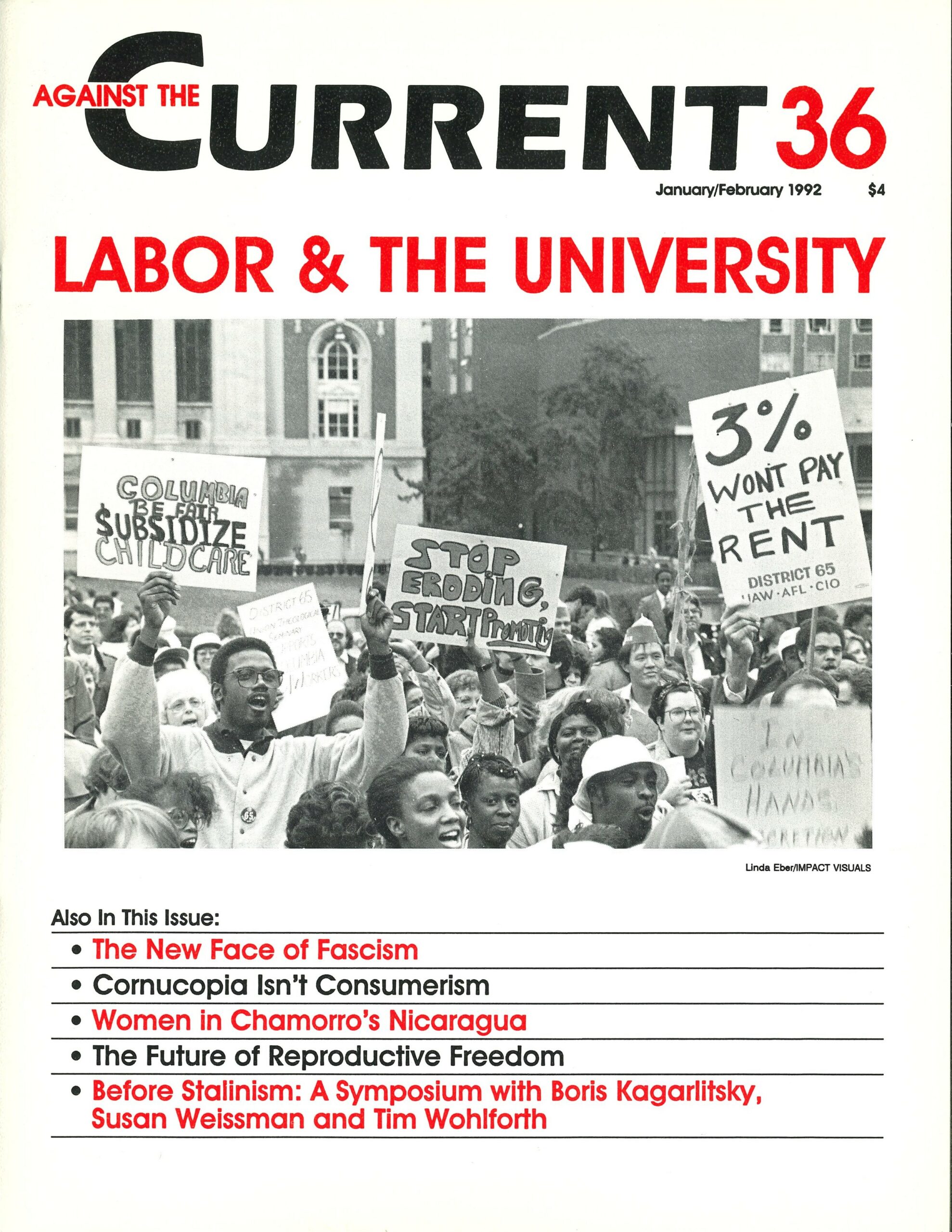

Campus in Crisis Introduction

— The Editors -

Labor and the Fight for Diversity

— Andy Pollack -

From Campus to the Unions

— Nicholas Davidson -

Higher Education on Auction Block

— Phil Cox -

A Proposal to Organize Non-Tenured Faculty

— Tom Johnson -

How to Read Cultural Literacy

— Richard Ohmann -

Introduction to Before Stalinism

— The Editors -

The Onus of Historical Impossibility

— Susan Weissman -

Between the Hammer and the Anvil

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

In The Grip of Leninism

— Tim Wohlforth -

Dialogue: On the Soviet Upheaval

— Ellen Poteet -

On the End of Stalinism

— David Finkel -

Bette Midler's "For the Boys"

— Nora Ruth Roberts

Nora Ruth Roberts

“FOR THE BOYS” is more than a vehicle for Bette Midler and James Caan, although they both display handsome talents. The film is Hollywood’s most important statement about the relationship between discourse and the question of war and peace, between discourse and reality since the aborted attempt to make something filmable out of Catch-22. And in the character of George Segal’s blacklisted gagwriter, there is something thrown in for the out and out radical.

The narrative structure is a discourse within a discourse about discourse. A young studio go-fer goes to the Hollywood apartment of fading has-been Dixie Leonard (Midler) to convince her to come to the studio extravaganza to accept an award from the President of the United States for her services entertaining the troops, along with co-star impresario Eddie Sparks (Caan).

Dixie Leonard, now quite old and in a housecoat, starts to tell the young man why she won’t go. The story unreels as a long scenarioed flashback.

Cut to the young Dixie getting her big break singing to the troops in 1942 Britain, stealing the show from a jaded star, Eddie Sparks. Dixie is married with a young son. Her husband (to whom she is faithful despite Sparks’ advances) is killed in the war.

Cut to the fifties when Sparks and Leonard are a big TV hit, bigger than Burns and Alan, Leonard’s foulmouthed broad with a heart of gold and a decency too thick to cut, playing off the charming but caustic Sparks. They are great together, but she still turns him down.

The split comes in Korea when they go to entertain the troops. There, the turning point comes when George (Art Segal), Sparks’ long-time gagwriter and Dixie’s uncle, is accused of subversive activity and the network forces Sparks to fire him. Dixie quits in protest.

Years are filled in—a club, some gigs. The only contact between Dixie and Eddie is through Dixie’s son Danny, who has looked to Sparks as a surrogate father. For his part, with a wife and three daughters he can hardly stand, Spark has taken Danny under his wing.

When Danny goes to Vietnam, Sparks is able to convince Dixie to do a show with him—like the old times, a live applauding audience. The place is raided by the VC and Danny dies. Dixie becomes bitter and never reconciles with Sparks.

Cut back to her living room where the young go-fer, affected by her story, is infected himself by a touch of radicalism or pacifism or just plain caring.

The final scene, the last meeting between Sparks and Dixie on stage, is reminiscent of Thornton Wilder’s Skin of Our Teeth; in that one has the sense of Mr. and Mrs. America carrying on with humor and a taint of affection, maybe even love, through a whirl of disasters–three wars–that has gone on over their heads.

Yet it is clear that the movie is raising the question of the complicity of Sparks and Leonard themselves, and their course, their songs and dances and comedy routines, in the very wars in which they cheer.

For socialists interested in the discourse question, this movie invites a fascinating meditation. The two elements we’ve all been talking about since the three-way discussion of Terry Eagleton, Raymond Williams and Jacques Derrida are all present.

The discourse, the entertainment the blab—what is its effect? On the other side are the bombs and the loss of live bodies; what could be realer to a woman than the Ioss of both her husband and son in gunfire? How does she deal with her own participation in the war effort when the President of the United States—in yet another discourse–attempts to give her a medal for service to the cause of the country?

Does somebody have to fight? Does somebody have to entertain? Does somebody have to sing him a song to help him feel better about it and lift his morale before the bomb drops so he can go on with the effort? All this provides the most meaningful disposition about the relationship of discourse to reality that I have had the occasion to conjure with since the publication of Catch-22.

This version has all the humor, all the pathos, all the value of Heller’s work but also has something in it for women. The sense is that we are all in this together, even the communist fellow-traveler played by George Segal.

The proof of the discourse is in the final effect of the discourse as discourse—the young man hearing the story, never himself involved in a war, is touched, moved, affected by Dixie’s story. There has been a shift in the subsoil. History has had some effect even on a guy who did not participate in it.

Discourse has had some effect—in this case an unequivocally positive effect. If the story has been a painful and complex one, at least there is some point in telling it. The radical community should be even more responsive to this film than the regular Hollywood crowd.

January-February 1992, ATC 36