Against the Current, No. 36, January/February 1992

-

1992: Seize the Time!

— The Editors -

Old Nazi in a New Suit

— Scott McLemee -

The Future of Reproductive Freedom

— Angela Hubler -

Women Under Chamorro's Regime

— Barbara Seitz -

Rebel Girl: Women, Sex and Disease--II

— Catherine Sameh - End the Blockade of Cuba!

-

Cornucopia Isn't Consumerism

— Jesse Lemisch and Naomi Weisstein -

Random Shots: Thoughts on Rivethead

— R.F. Kampfer -

Campus in Crisis Introduction

— The Editors -

Labor and the Fight for Diversity

— Andy Pollack -

From Campus to the Unions

— Nicholas Davidson -

Higher Education on Auction Block

— Phil Cox -

A Proposal to Organize Non-Tenured Faculty

— Tom Johnson -

How to Read Cultural Literacy

— Richard Ohmann -

Introduction to Before Stalinism

— The Editors -

The Onus of Historical Impossibility

— Susan Weissman -

Between the Hammer and the Anvil

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

In The Grip of Leninism

— Tim Wohlforth -

Dialogue: On the Soviet Upheaval

— Ellen Poteet -

On the End of Stalinism

— David Finkel -

Bette Midler's "For the Boys"

— Nora Ruth Roberts

Phil Cox

MASSACHUSETTS LED NEW England, which led the nation, into the current recession. Now the Commonwealth has a great shot at being the top of the Rust Belt heap in dismantling the social welfare initiatives it inherited from the 1960s and 1970s.

Public funding for higher education was just the first to take the hit. Massachusetts has the fourth highest per capita income in the nation, yet is the only state, for the fourth year now, to cut funding for public education. State appropriations for education are down over $200 million from 1987 levels. (A proportionate cut in defense spending, for instance, would leave the Pentagon a three-and-a-half-sided building.)

One of the few perks in this continuing crisis has been the notable rise in dark humor on the campuses. After the third year of cuts, the cry was not for restoration of 1987 levels, but for just enough money to bring us up to the level of education spending for state #49, Louisiana. This in a state which harbors institutions such as Harvard and MIT, hardly a country mile from the statehouse, which sit on prime real estate and pay absolutely no taxes.

At the flagship public research university, UMass/Amherst, the annual July social for incoming faculty, of which there are none, has been supplanted by a social for nervous incoming and interim deans, of which there are five—the lucky finalists in a contest for deandoms, the more sane candidates eliminated by virtue of being overqualified.

The nonsense gets greater, though, the higher up you go. A member of the Trustee Board of UMass recently argued, echoing his friends in the statehouse, that higher education has not yet privatized and downsized as it ought in these times of recession and austerity. This trustee, questioning a dean who had lost twenty-five percent of his faculty through attrition and departments dosing, wondered aloud whether there had been any “real layoffs,” for example in the departments of “chemistry, physics, or astrology” (none of the state’s twenty-nine campuses have ever even offered a curiosity courset in astrology). He further inquired as to how many of the “thousands of programs and departments” at UMass/Amherst had been scaled back or closed (UMass offers a mere sixty-eight Ph.D.-granting departments). And these are the people in charge at the top.

Trickle-Down Tragedy

There is, though, a very serious and very real trend in which Massachusetts leads the rest of the states in public higher education, and beyond that in human and social services generally. The old “New Federalism” of the Reagan/Bush ’80s has finally trickled down, though it took a decade in the making. Reagan initiated the closure of federally-assisted state services in 1983, and the effect has now reached down to state and local governments.

The feds for a long time now haven’t given the money to bankroll what used to be consensus platforms of social welfare—general relief, food stamps, child care assistance, welfare, urban transportation and infrastructure, unemployment assistance, health care for lower income people, public education. (A sour footnote health care: When a sitting governor ran for national office, Massachusetts bragged of big plans for state-run universal health insurance. We’ve all but forgotten that idea, and now the current governor wants state employees to increase by 150% their payments towards their own health insurance).

State governments in the late ’80s were thus faced with the choice of dramatically scaling back or eliminating these programs, increasing revenues somehow, or using red ink to short-term fund them. Those states with the most liberal commitment to these programs—New York California, Massachusetts among them—found themselves quickly in a remarkable fiscal crisis.

Massachusetts, having only “soft” industries as real estate and hi-tech, leaped into this crisis first, with one foot in the recession. Results have not been promising. The “prosperity” of the Reagan ’80s is only now coming to be seen as a fraud: There are now 700 more millionaires than in 1980, yet real wages in 1991 have not risen over 1973 levels. Similarly, voters in the Commonwealth have refused to consider any type of tax initiative or reform to bring services back to pre-Reagan levels, even in the face of cuts polls indicate we all lament.

Everybody feels like what’s happening around us is being done by someone else, to the rest of us. Call it fiscal mismanagement. Call it bureaucratic red tape and inertia. The real story has much more to do with the redistribution of income that Reagan manufactured and his successor has maintained.

Massachusetts is not alone in suffering the trickle-down of federal cutbacks, and the state fiscal crisis that will precipitate. The governors of Connecticut and Maine this last June shut down state services, declaring a fiscal emergency. New York and California are a hair away. Just in higher education, New York is implementing $152 million rollback, California a negative $402 million, and even then they’re counting on budget red ink. If the states most committed to progressive fiscal and social policy give it up, what of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana?

Crunching the Campuses

An argument could have been made, in the first years of cuts (’87-’89) that higher education cuts were something of a political accident, an ostensible quick-fix for what everyone hoped would be a passing budgetary shortfall. Legislators hoped to cut higher education once (or twice), dodge the political fallout, make declarations of commitment to public education, and hope there’s more money next year.

But what may have been a trial balloon became a juggernaut in ’88-‘91: With each cut in education, legislative, executive branch, and lay board cries for layoffs, department eliminations, and permanent “downsizing” have risen in pitch. Not too quick to catch on, campus administrators for the last two years have hyperinfiated tuition and “temporary” fees to alleviate the cuts to their campuses. (Fees are up forty-seven percent this year at UMass/Amherst, over one hundred percent at some community colleges; this is over last year’s tuition and fee increases, which were themselves records. UMass is now the second most expensive public university in the nation.)

Downsizing the public sector no longer appears to be a short-term fix; legislators have made it clear they lack the political will to talk about tax reform or increases to fund services cut short by the feds. Unlike other state agencies which depend entirely on state and federal appropriations, education administrators have resorted in their desperation to inventing and then doubling and tripling fees they can keep on campus. What they too easily lose sight of is the consequent privatization of public education, and the decline in access that must follow those radical shifts of costs to students.

Yet while tax reform hasn’t fared much better at the polls than the Legislature, popular resentment of drastic cuts in services is fueling grassroots initiatives for more equitable tax and fiscal restructuring. The Tax Equity Alliance of Massachusetts, which played a major role in defeating what would have been a suicidal tax cap referendum last November, is just beginning a longer-term campaign for progressive tax reform (astonishingly enough, a graduated income tax is illegal under the current state constitution).

Organize to Resist

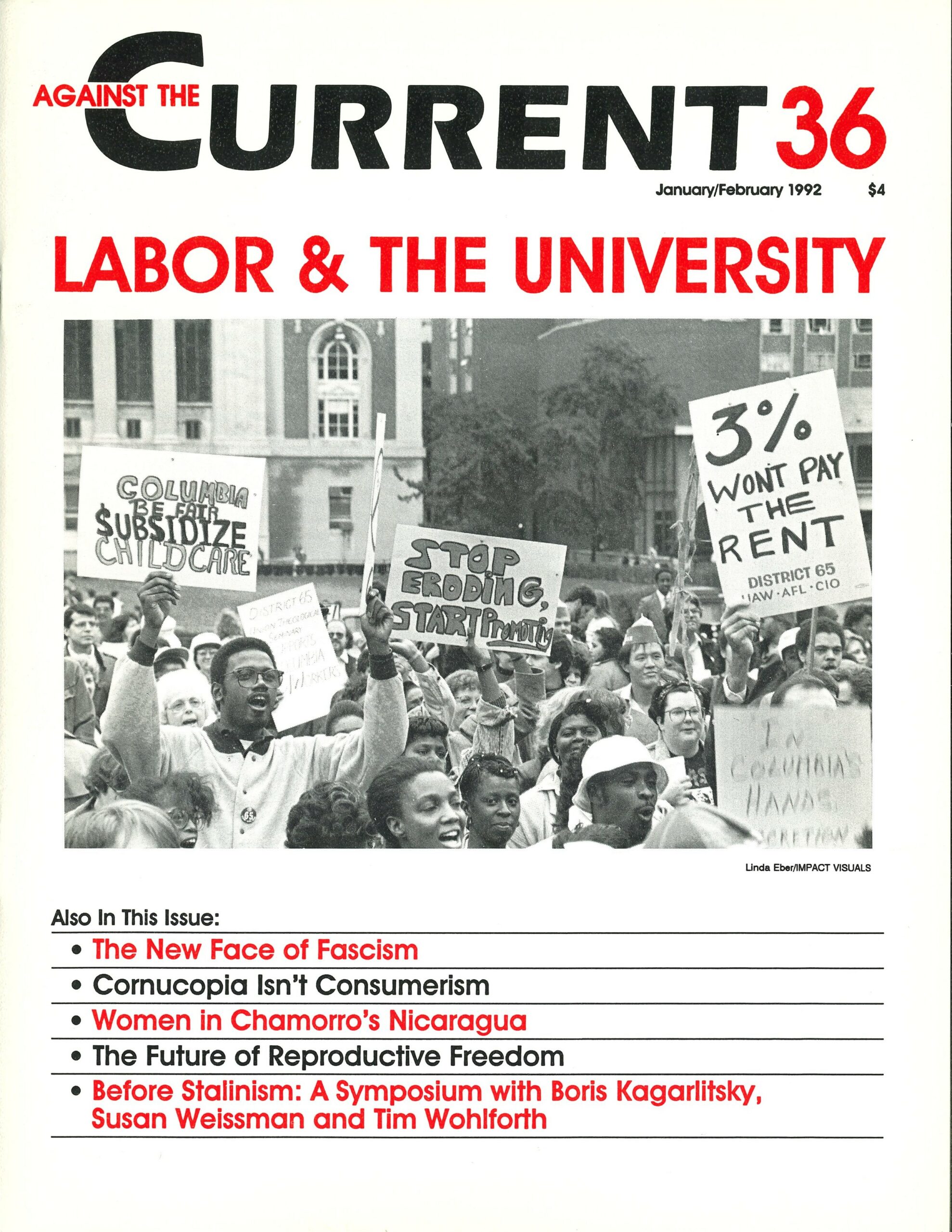

At UMass/Amherst, nearly all of the workers on campus (including faculty, professional, clerical, and maintenance staff) have formed unions and have worked well together in campus actions. This last May the faculty walked out in protest of the cuts in health care and an up to ten-day furlough/pay cut, and was strongly supported by the students and other unions.

Graduate employees on campus (Teaching and Research Assistants), 2500 in all, after a ten-year fight to have their work recognized as “labor,” affiliated with District 65/UAW and won a representation election this last fall. While some of the other half-dozen campuses nationwide that have union representation for graduate employees have affiliated with larger unions, the graduate union at UMass was singularly lucky in the amount of staff and financial support from District 65 and UAW.

The graduate union at UMass may be bargaining their first contract in the worst of times, but the gains they’ve made in fighting retrenchment, improving working conditions, and in rescinding fee increases have been substantial. It remains to be seen whether big labor dollars will be committed to union drives at campuses in other states (interest in unionization in higher education is dramatically increasing as cutbacks loom across the nation), but the UMass example offers hope.

Of course, money is not the cause of the only crisis on the nation’s campuses, as struggles over campus racism and attacks on multiculturalism and curriculum reform show. But it’s a big one, and other crises on campuses can be much harder to approach when there’s constant scrambling and competition for declining dollars. As New England is mired in the worst of the recession and in public policy crisis, we hope the next states to go through this will learn from our bad example, and envision a more forward-thinking and progressive response to bad limes.

January-February 1992, ATC 36