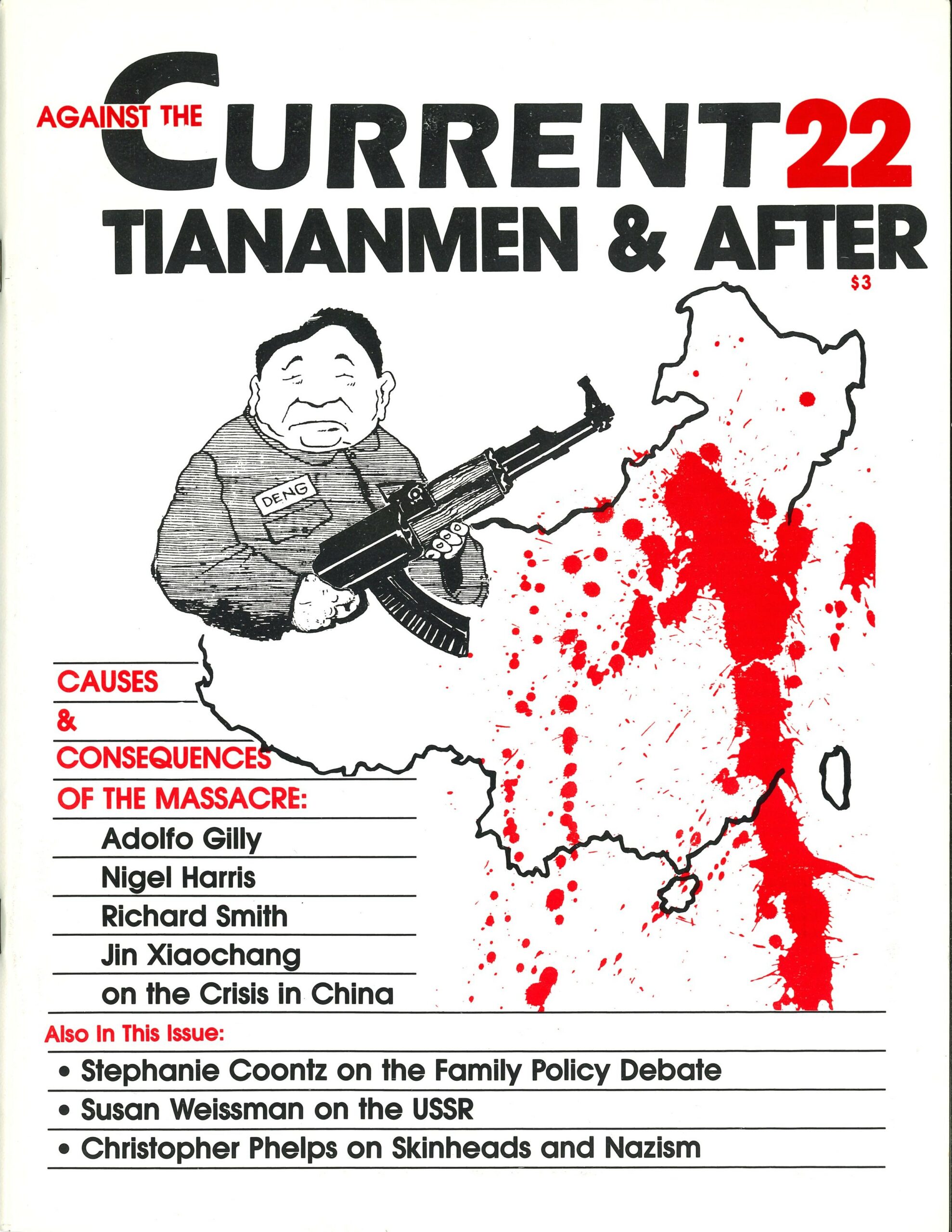

Against the Current No. 22, September/October 1989

-

Defending Women's Lives

— The Editors -

Editor's Note

— The Editors -

Skinheads: The New Nazism

— Christopher Phelps -

LA Teachers Win in the Streets

— Joel Jordan -

The Pitfalls of "Family Policy"

— Stephanie Coontz -

Back in the USSR, Part I

— Susan Weissman -

The Soviet Working Class Enters the Stage

— Susan Weissman - China After the Massacre

- Brief Chinese Chronology

-

What the Chinese Students Fought For

— Sungur Savran interviews Jin Xiaochang -

Counterrevolution and Crisis

— Nigel Harris -

Teng's Reforms, Neither Market Nor Socialism

— Richard Smith -

Proposals by the Beijing Independent Workers' Union

— Provisional Committee of the Beijing Independent Workers' Union -

The Old in the New--the New Through the Old

— Adolfo Gilly -

Letter: Blaming A Victim for Tiananmen?

— Aleksei K. Zolotov, Washington, DC - Review

-

The Empire and the Old Mole

— Michael Fischer -

Random Shots: A Kind and Gentler Ollie?

— R.F. Kampfer

Susan Weissman

THE PREVIOUS ARTICLE, “Back in the USSR, Part I,” was written before the spectacular strike wave of Soviet miners in July 1989. The basic analysis stands. But the class activity of the Soviet workers is now underlining the point that the working class is the decisive factor in perestroika and Soviet society.

The strike, which began in Siberia and spread through Kazakhstan to Ukraine, enveloped mines from the Kuzbass to the Donbass regions. Mine after mine shut down in places like Mezhdurechensk, Kemerovo, Vorkuta, Makeyevka, Rostov on Don, Lvov, Karaganda in Kazakhstan, and Prokopyevsk in the Kuzbas.

Strike committees formed in each strike area, although they did not communicate with each other. News of the strikes was carried in both the official press and television. Instead of sending in the troops, Gorbachev quickly acceded to all the strikers’ demands.

The miners themselves live in extremely poor conditions. They still live with their families crowded into barracks that were built in the ’30s when the mines were opened and populated with camp inmates.

Many families live 5-6 to a room and must share toilets with several other families. Since there is a shortage of soap all over the Soviet Union this year, the miners have no way to dean themselves after a day in the pit.

The strikers’ demands range from the general to the specific: they demand better pay and housing, greater political power, a cleaner environment, as well as winter shoes and soap. They are opposed to private enterprise, called the “cooperative” movement in the Soviet lexicon.

Their environmental demands are a response to the filthy cities they live in. Moscow News reported the Kemerova and Mezhdurechensk are among the ten dirtiest cities in the world. Moscow People’s Front activist Boris Kagarlitsky, who traveled to the Kuzbass region, reported to this writer (interview, August 6, 1989) that not a single “polite” word was spent on perestroika or Gorbachev—although there were no verbal attacks against Gorbachev.

The strikers are back at work, although according to Kagarlitsky the miners “suspended” rather than ended the strikes. The Vorkuta miners resumed the strike over the weekend of August 56, when local authorities told them they didn’t have the resources to implement the demands they’d won.

No repression has been documented thus far, nor noted by Boris Kagarlitsky, who addressed the Kuzbass workers’ rallies as the representative of the Initiative group within the Moscow People’s Front.

Kagarlitaky said a revolution has taken place in the hearts and minds of people across the Soviet Union. The strikes have counterbalanced the nationalist struggles of the various nationalities, replacing them with the fundamental class conflict of workers whose lot is universal.

At Karaganda in Kazakhstan, the strike committee took over the mine and made it into a self-managing enterprise. Dual power exists in Kemerova and Karaganda, where the strike committees form a center for alternative power.

The most significant achievement of the strikes is that the Soviet working class has shown itself as a force to be reckoned with, and demonstrated that there will be no movement in the Soviet economy without the working class. Despite the weaknesses of the new strike committees (lack of coordination, the tendency to come under the influence of one or another local authorities) their demands and organization demonstrate their seriousness.

Many of the miners have called for independent trade unions and a new Socialist Trade Union was registered in Moscow in August by the Initiative group. Interest was also expressed in independent socialist political organization, Kagarlitsky said.

September-October 1989, ATC 22