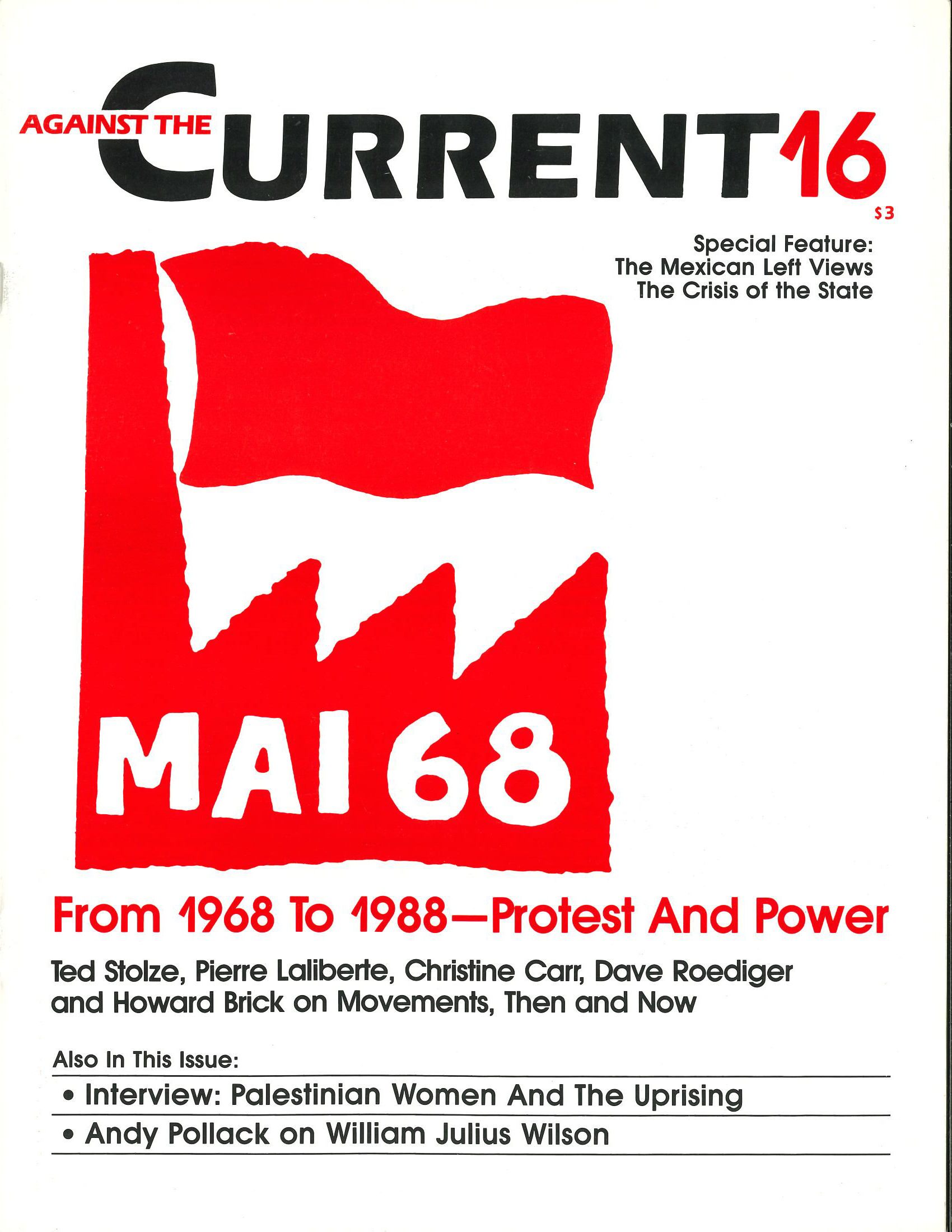

Against the Current No. 16, September-October 1988

-

The Rainbow and the Democrats After Atlanta

— The Editors -

Palestinian Women: Heart of the Intifadeh

— Johanna Brenner interviews Palestinian activist -

Critique of William J. Wilson: The Ignored Significance of Class

— Andy Pollack -

Ramdom Shots: Libs, Labs and Lawyers

— R.F. Kampfer - From 1968 to 1988

-

1968 and Democracy from Below

— Ted Stolze -

Lessons from the Campus Occupation

— Pierre Laliberté - Summary of Occupiers' Demands

-

USC Women Demand an Autonomous Center

— Christine Carr -

Something Old, Something New

— Dave Roediger -

The Participatory Years

— Howard Brick - Mexico: The Crisis, the Elections, the Left

-

Mexico: The One-Party State Faces a Deep Political Crisis

— The Editors -

The Need for a Revolutionary Alternative

— Manuel Aguilar Mora -

The New Stage and the Democratic Current

— Arturo Anguiano -

Call for a Movement to Socialism

— Adolfo Gilly and 90 others - Dialogue

-

Radical Religion--A Non-Response

— Paul Buhle -

Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere

— Justin Schwartz - An Appreciation

-

Raymond Williams, 1921-1988

— Kenton Worchester

Kenton Worchester

RAYMOND WILLIAMS’ recent death at the age of sixty-six comes as depressing news for all those who have enjoyed his many essays, novels, and works of literary criticism.

While it is probably misleading to think of Williams as “the main voice of Britain’s New Left,” as the New York Times reports, Williams’ eclectic radicalism has appealed to activists inside and outside the Labour Party for more than thirty years. (There were two British new lefts, the first emerged in the early 1960s around the banner of anti-nuclear unilateralism, the second came into being during the magical year of 1968. Williams was associated with the first.)

Williams’ impact on the required texts, and on media studies, has been profound. His novels depict daily life in the “border country” of his Welsh youth; and his influential political articles address the prospects of “the long revolution”: that is, the transition from liberal capitalism to a radically-democratic culture and economy.

Raised in a small farming village (his father was a railway worker), Raymond Williams was decisively shaped by the family’s decent, social democratic values. In 1939, at the age of eighteen, he joined the Communist Party at Cambridge University. Although he remained vaguely pro-Communist while serving as a tank officer in the British Army (taking part in the invasion of Normandy), he lost interest in organized politics on returning to Cambridge in 1945.

Part of the explanation for this withdrawal from politics had to do with his growing disenchantment with the fairly crude “dialectical materialist” conceptions of literature he picked up from the Party. “Not only was I hostile to Jane Austen, and interpreted Dickens or Hardy in a very simplifying way as just progressive,” he later recalled, “I would also talk about the romantic poets, insisting that they represented a project of human liberation which was going to be completed in the future.”

Throughout the drab ’50s and beyond, Williams concentrated on finding a way of talking about literature that didn’t reduce novels by Jane Austen to her “middle-class liberalism.” A series of well-received titles–including Culture and Society:1780-1950 (1958) and The English Novel From Dickens to Lawrence (1970)—analyzed “the great books” of the canon in the context of both the material constraints and pressures operating on writers, and the intellectual history of the ideas which shaped English culture.

The aim was not to lessen literature’s appeal, nor to rob the great books of their individuality; it was, rather, to “historicize” literature in order to illuminate the interstices of art and society.

Culture and Society describes how two contending definitions of the word “culture” (culture as a way of life versus culture as high art) signify two radically different approaches to capitalism. The dominant, elitist view of culture justifies social inequalities on the grounds that only the rich can create, judge and preserve culture.

Developing the ideas of such nineteenth century thinkers as William Morris, Williams critiqued elitist readings of culture which deny the aesthetic values embodied in “general skills, from gardening, metalwork and carpentry to active politics.”

In this view, the formation of, say, trade unions has a quasi-aesthetic quality: “Working class culture, at the stage through which it has been passing, is primarily social (in that it has created institutions) rather than individual … it can be seen as a very remarkable creative achievement.” From the perspective of “culture as a way of life,” the self-organization of workers takes on a rather attractive hue.

Culture as A Way of Life

Because of the success of Culture and Society, Williams was given a teaching position at Cambridge in 1961; in 1974 he was made Professor of Drama. His reputation was sustained through some fairly dense interventions in media and language studies: see Television, and Keywords (both 1974).

Keywords was supposed to appear as an appendix to Culture and Society, but was cut for reasons of space. It presents the history of several dozen “words that are key to understanding our society.” The meaning and connotations of words like “class” and “industry” often change in ways which reveal certain facts about power and authority in society.

One can draw several connections between an effort to refocus the canon towards “culture as a way of life” and an infatuation with the sociology of language and the media. The key point is that Williams was challenged to construct an approach to literature that avoided the pitfalls of economic reductionism and ”art-for-art’s sake” idealism.

Instead of bashing Jane Austen, or pandering to the romantic English poets, he emphasized the potent turbulence of culture, broadly defined. Cultural struggles over language, ideas, and even politics live in the great books, and a grasp of these struggles is integral to the study of literature.

Novels by Thomas Hardy, in this view, might be read in conjunction with William Cobbett’s journalism; not in order to reduce Tess to the events of the day, but rather to highlight the common, suggestive concerns-from political goals to the ambiguities of certain words–which may be said to link the projects of Hardy and Cobbett. Williams’ approach is sometimes called Gramscian in the way it emphasizes history’s complexity and takes culture questions seriously.

For many years, it wasn’t clear where Williams stood in relation to Marxism, and his delicate theories seemed more Continental than home-grown. But, by the late 1950s, he was politically active again in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, in the local Labour politics, and in founding New Left Review. Along with E.P. Thompson and Stuart Hall, he drafted the May Day Manifesto in 1966-67, which spawned some short-lived political clubs. It reads a little like a pro-worker “Port Huron Statement.”

In Marxism and Literature (1977), Williams comes close to embracing a kind of structuralism, and in Politics and Letters (1979), a collection of interviews with New Left Review, Williams backs away from some of the more nebulous and humanistic arguments made in Culture and Society and elsewhere. But The Year 2000 (1983) brings together several heterodox essays which defend a socialist humanism. He writes:

“It is my belief that the only kind of socialism which now stands any chance of being established, in the old industrialized bourgeois-democratic societies, is one centrally based on new kinds of communal, cooperative and collective institutions. In this the full democratic practices of free speech, free assembly, free candidature for elections, and also open decision-making, of a reviewable kind, by all those concerned with the decision, would be both legally guaranteed and, in now technically possible ways, active.”

In a preface to The Year 2000‘s American edition, he complained about how “it is not only offensive but deeply injurious to democracy to have a president of the United States described-and believing himself correctly described-as a leader of the West or of the Free World.”

“One of the new overpowering American universals,” he added despairingly, “is an absolute contrast between democracy and socialism, whereas we are not simply radicals or liberals but committed socialists, if in some ways of a new kind. This is now one of the harder areas of intellectual negotiation across the Atlantic.”

Several of the books I’ve mentioned have a slightly cramped style. Culture and Society, for example, while full of evocative phrases and trenchant digressions, lacks a certain smoothness. Of the later, explicitly Marxist books, only The Year 2000 stands out in terms of presentation. Sometimes the ideas lack focus. The Volunteers (1976), a novel about a radical group which infiltrates London’s establishment, seems to come straight out of the author’s notebook.

Celebration and Frustration

Two of his best books were written in the early 1970s, after his disenchantment with labourism but before he fell in with NLR. Orwell (1971) provides a subtle, and movingly written, reappraisal of the famous novelist and critic of “totalitarianism.”

Heavily criticized at the time for what to me seems its admirable evenhandedness, its perspective is that the “thing to do with his [Orwell’s] work, his history, is to read it, not imitate it. We are acknowledging a presence and a distance: other names, other years; a history to respect, to remember, to move on from.”

While suitably respectful of Orwell’s experiences in the Spanish Civil War, the biography is less positive about the politics of 1984 and even The Road to Wigan Pier, which he sees as “sketches towards the creation of his most successful character, ‘Orwell.’”

The Country and the City (1973) explores English poetry inspired by the countryside and country-houses. It opens with a few observations about the words “country” and “city” and “how much they seem to stand for in the experience of human communities.”

What they often stand for is the status quo. As Matthew Arnold wrote about country-houses, “When I go through the country, and see this and that beautiful and imposing seat of theirs crowning the landscape, “There,” Is ay to myself, “is a great fortified post of the Barbarians.”

More often than not, however, English critics, novelists, and poets celebrated the environment of country-houses and those who owned them: “God bless the squire and his relations/And keep us in our proper stations.”

Orwell, and The Country and the City are characterized by a sharp ambivalence about English literature and life, which is obviously informed by their author’s “border country” upbringing. As they celebrate a gamut of English cultural achievements, they express nothing but frustration and loathing for the core values of the dominant English classes.

Looking Backward and Forward

Readers can look forward to Williams’ forthcoming collection of essays and lectures, Resources of Hope (Verso, 1988).

Williams’ work is shaped by a profound uneasiness with the fruits of modernity. It seems fitting, somehow, to end with a passage from Thomas Moore’s Utopia (1519), quoted in The Country and the City, which speaks to Williams’ distinct brand of (pastoral? egalitarian? Welsh?) socialism:

“Suffer not these riche men to bie up al, to ingrosse and forstalle, and with their monopolie to kepe the market alone as please them. Let not so many be brought up in idelness, let husbandry and tillage be restored, letclotheworkinge be renewed, that ther may be honest labours for this idell sort to pass their tyme in profitablye.”

September-October 1988, ATC 16