Against the Current, No. 15, July/August 1988

-

Central America: Danger and Hope

— The Editors -

Hidden Life of Project D

— Tim Krause and Zoltan Grossman -

Fighting for the Homeless: Some Thoughts on Strategy

— Steve Burghardt -

Civil Rights and Self-Defense

— John R. Salter, Jr. -

Their Technology -- and Ours

— Nancy Holmstrom -

Shachtmanites & Cannonites: Socialist Politics After Hungary '56

— Tim Wohlforth -

Chile: Building from the Grassroots

— interview with Martin Garate -

Comment on Victor Serge

— Gerd-Rainer Horn -

Appeal Isareli Press Censorship

— Joel Beinin, John Kelley, David Millstein & Zachary Lockman -

Random Shots: Fur Files in Eco-Wars

— R.F. Kampfer - Dialogue

-

An Introduction: Jesse Jackson, Rainbow Politics & the Future

— The Editors -

What Do Some Socialists Want?

— Charles Sarkis -

The Problem Is Electoralism

— Wayne Price -

Latino Politics & the Rainbow

— interview with Angela Sanbrano -

Will the Rainbow Face Reality?

— Mel Leiman -

An Alliance for Empowerment

— an interview with Abdeen Jabara -

What Jackson Built -- And Didn't

— Joanna Misnik - Reviews

-

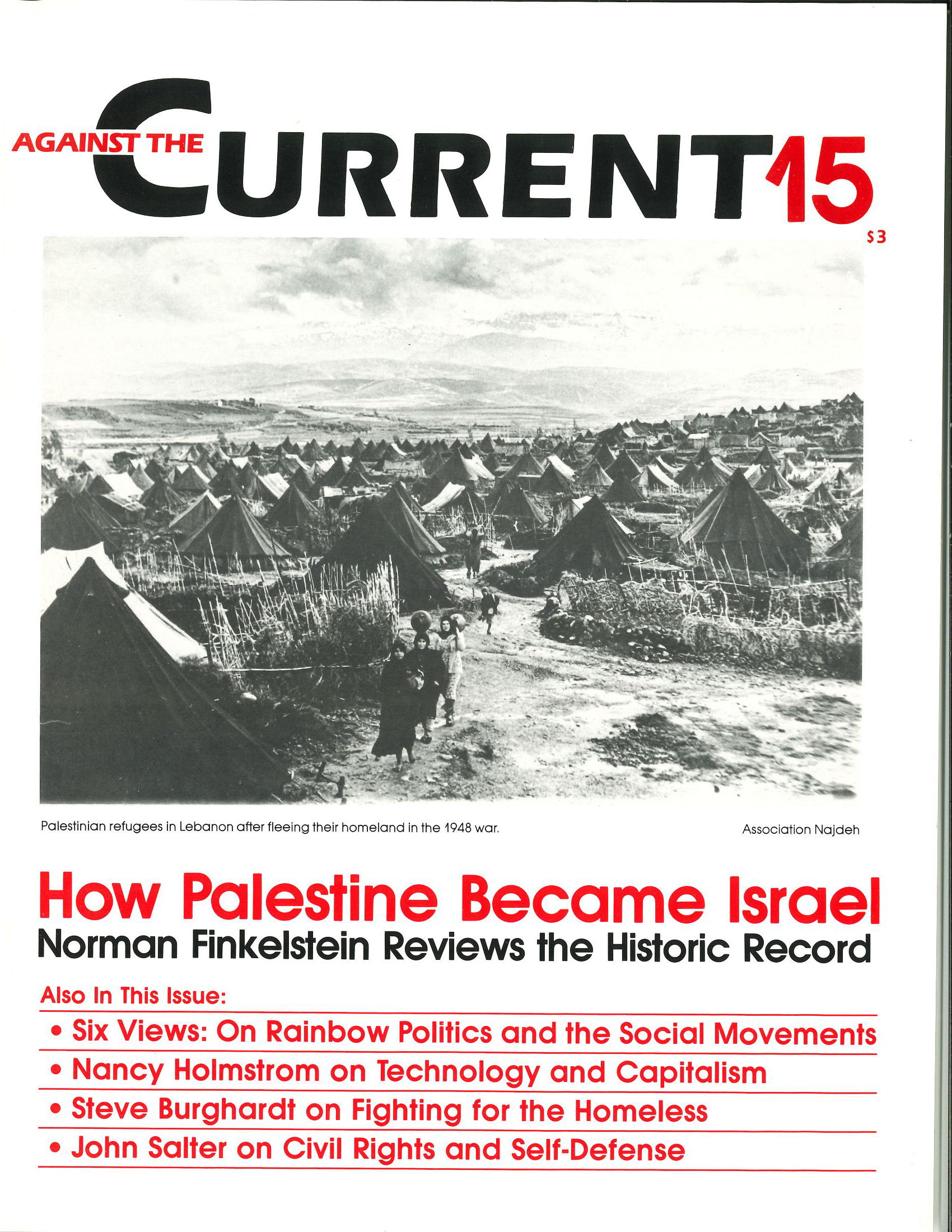

Palestine: The Truth About 1948

— Norman G. Finkelstein -

Sex as Work and Industry

— Leslie J. Reagan

interview with Martin Garate

Martin Garate is a Chilean activist. Deeply involved in the social and political struggles of 1970-73, he was forced to flee his country following the Pinochet coup of Sept. 11, 1973. He returned to Chile in 1980 and helped found Servicio de Comunicaciones Populares (SECOP), a popular communications project working in poor neighborhoods in Santiago.

Garate visited Detroit early in 1988 as a guest of the Latin America Task Force (LATF), a local solidarity group organized by churchbased activists, many of whom have lived and worked in Latin America. ATC editor David Finkel interviewed him to learn about the perspectives of the Chilean movement today.

Against the Current: Why has the Pinochet regime lasted longer than the Left anticipated?

Martin Garate: When the coup happened, it really threw the left into disarray for several years. At the level of the cadres, more than top leadership, people were killed or fled into exile. Those who did grassroots work were the main victims. It took a long time to reorganize under clandestine conditions, with continuous repression by a very sophisticated security police.

There was also a lot of in-fighting among sectors of the left over who was responsible for the coup, whether by pushing too hard or because there was not enough change. All this gave Pinochet the chance to consolidate the military regime, as well as his support from the right and center parties.

There is still no cohesive alternative plan to Pinochet’s objective of creating a “new society.” The opposition remains divided. The popular mobilizations of 1983-85 shook the government, but the opposition lacked the strength to create a general strike to bring down the government.

Unions in the industrial sector suffered greatly in the 1980-SZ recession. Many industries just collapsed in that crisis. In the ones left, especially copper mining, the workers were afraid of striking for fear of losing their jobs – it was scary when we had over 25 percent unemployment. The unions were also divided on political lines.

Most of the protests were in the neighborhoods — the economy was not stopped. So Pinochet was able to survive. Then in 1986, when there was a general strike, we understand there was pressure from the U.S. State Department on the Christian Democrats to discontinue their cooperation with the left. So the CDs pulled out in exchange for U.S. support.

ATC: Please explain further the political lines in the unions and the workers’ movement.

Garate: In general, both the Communist and Socialist parties have tried to have an agreement with the Christian Democrats [the main capitalist party] to bring down the government since they felt they could not accomplish it by themselves. The CDs have agreed only to tactical alliances, for specific protests, not a political alliance….

Some parties of the left were for collaboration with the CDs in mass protests and at the base, not at the leadership level. This is the difference between, say, the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR, an underground party) and the CP, in relation to work with the Christian Democrats.

When the CDs pulled back, the left came together at the end of 1983 in the MDP, an alliance of the CP, SP and MIR. The MDP ended this past year (1987) because the left fought to broaden the spectrum of the MDP and formed the “Unified Left,” to make it more appealing to the Christian Democrats. This Unified Left includes the CP, SP, Christian Left and Movement for United Popular Action (MAPU). It includes also a sector of the MIR, which split in 1987 over questions of political tactics and the combining of mass rnobilization with armed struggle.

ATC: Without discounting the importance of party politics, what does the day-to-day movement at the base lock like?

Garate: The poor neighborhoods are the most combative social sectors. Most of those participating in the protests are young people. Another very active and militant sector is the university students, who struck for two months in 1987 against the government’s appointment of the university director. They also opposed a plan by the government to make the university much smaller, more a professional training school than a place for the pursuit of knowledge in philosophy, social science and so forth.

In the poor neighborhoods the Left has much more organization. The Christian Democrats have more strength in the middle class — not that they have no presence in the poor neighborhoods, but the Left is much more important there. The Communist Party, being the oldest and most prestigious, is the strongest and has not suffered divisions like many other socialist groups.

Christian Base Communities are quite active, with very little support from the Church hierarchy, which is very worried about what they call the “popular church.” Many of the priests who worked in the poor sector were foreigners, and have been thrown out. So my impression is that the Base Communities have less strength than three or four years ago. The Church is much more conservative in appointments of new priests.

ATC: As we understand it, the Pinochet regime has developed a sophisticated project for a “New Order.” How do you evaluate it?

Garate: The regime in Chile is quite unique in Latin America; far-sighted in a way that the regimes in Argentina and even Brazil never were. They have a comprehensive program for reshaping society. That’s what we are up against; there is no effective counterstrategy at the moment.

The Constitution of 1980 basically preserves the present order for the benefit of the upper class, and also gives extraordinary power to the armed forces. It creates a new organization called the National Security Council to oversee any future government, with the power to overrule any government measure. The heads of the armed forces have controlling votes in this Council.

Pinochet calls his Constitution a “protective democracy” so the left can never come back to power. Almost a third of the Senate are there by virtue of office or presidential appointment — the heads of the armed forces, police, ex-presidents, etc.- – and the House of Representatives has very little power. The Constitution will never be able to be changed from within.

The regime has borough-level neighborhood organizations to carry on the policies of the government at the local level. At the same time, Article 8 basically bans the Left from being legitimate political parties. People who hold socialist views cannot be teachers, public officials, union leaders — they are only to be able to vote, but not really be citizens.

In the long run, I think there is strength in the grassroots movement. People want change. At this moment, however, I don’t think the opposition has a clear strategy. This has given the government the capacity to be more assertive.

Today it has the upper hand and is moving very hard for a plebiscite at the end of this year, authorizing a transition to an II elected” president where the candidate will be chosen by the military. I don’t think the opposition can defeat the plebiscite; even if they do, the government will claim victory. And while it’s hard to predict, I see a very difficult period ahead.

ATC: Having lived in Chile during the Popular Unity period and especially the crisis of summer 1973, and now observing what’s happening to Nicaragua with the contra war and U.S. economic warfare against the Sandinistas, how do you see the similarities or differences in the situations?

Garate: I lived in the slums during the Allende government. The people felt it was their government that it was trying to respond to their needs. There was a lot of enthusiasm, although times were difficult.

By the middle of 1973, food was a big problem. But people got organized. Where I lived, we were able to go to distribution centers and get the food we needed for the week. The people had a much better time than today, when there’s plenty of food in the markets but they have no money to buy it.

The health system was much more humane, there were educational possibilities, and no more than 2 percent of the population was unemployed — so the poor sectors really felt it was their government In fact, the congressional election of 1973, when the Popular Unity increased its vote to 43-44 percent, was what showed the opposition that they couldn’t stop Allende through elections.

Many people in the poor neighborhoods look back to Popular Unity years as the best time. To be sure, 1974 would have been very difficult if the government hadn’t made radical changes – factory owners weren’t investing, profits were flowing out of the country, inflation was becoming extreme.

In Nicaragua today, the U.S.-contra opposition tactic is to make the situation so terrible that people begin to turn their backs on the government. Then they hope military action would bring down the Sandinistas.

The problem is that there isn’t enough time for the Sandinistas to work at the grassroots level, to empower the mass organizations enough … so my fear is that if the economic situation in Nicaragua goes much further the people might begin to abandon the government.

But I don’t know that much about Nicaragua. Maybe the popular organizations are stronger than I think. The basic problem, I think, is for the government to finish the war so they can restore the economy and the reform programs, so people get some benefits from their sacrifices.

The situation is very difficult. But the difference in Nicaragua is that the people won; they control the structure. In Chile the power structure was never controlled by the people, nor even by the President. He had only the executive office. The legislative, judicial and military weren’t controlled by the people.

In the poor sectors today in Chile there is great interest in Nicaragua. People would feel very bad if something happened to the Nicaraguan process. The Nicaraguan example gives people the hope that it can happen in other places. It is the hope for the people of Latin America.

July-August 1988, ATC 15