Against the Current, No. 11, November-December 1987

-

The Crash of '87: Opening of a New Period?

— The Editors -

The Rainbow: Storm Clouds Ahead?

— Joanna Misnik -

Vanunu and the Israeli Bomb

— Stanley Heller -

Alan Garcia & the Crisis of Populist Rule in Peru

— Scott Malcomson -

On Sendero Luminoso -- Shining Path

— Scott Malcomson -

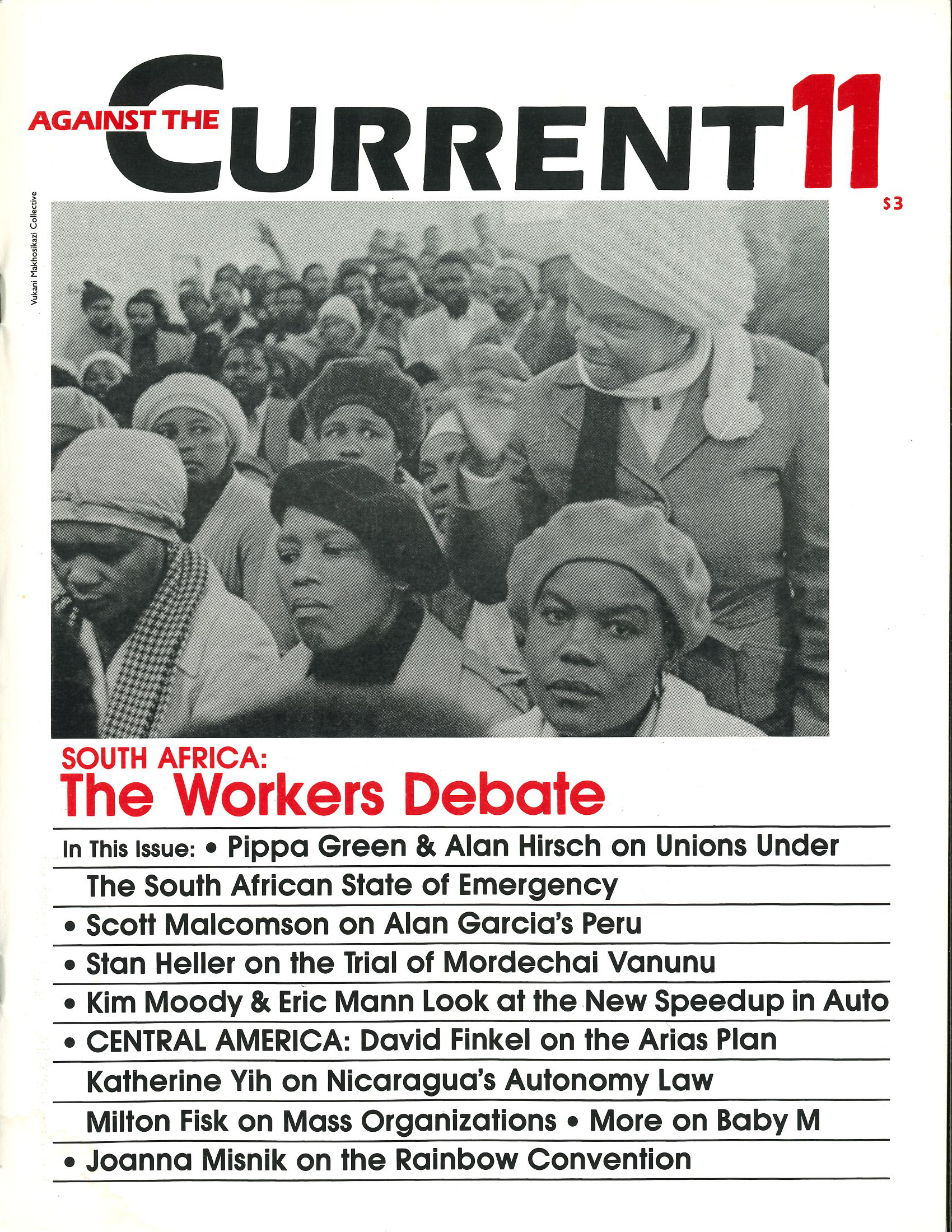

South Africa: The Black Unions & the State of Emergency

— Pippa Green & Alan Hirsch -

South African Unionists Back Divestment

— John Gomomo - Guidelines for Divestment

-

Of Scrooge, Bentham & Reagan

— Paul Siegel -

Random Shots: Pat Robertson's Miracle

— R.F. Kampfer - Auto Unionism in Crisis

-

It's Their Crisis -- But Our Jobs

— Robert Brenner interviews Eric Mann -

New Speedup in Auto

— Kim Moody - Central America

-

Central America's Peace Plan & the US. Solidarity Movement

— David Finkel -

CISPES: Challenge of Solidarity

— David Finkel -

Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast Dialogue: Autonomy & the Revolution

— Katherine Yih -

The FSLN, Mass Organizations & the Socialist Transition

— Milton Fisk - More Debate on Baby M

-

Debate on Baby M

— The Editors -

Protecting the Mother's Right Is Critical

— Nancy Holmstrom -

A Reply to Our Critics

— Johanna Brenner & Bill Resnick - In Memoriam

-

Harvey Goldberg: An Appreciation

— Patrick M. Quinn

Scott Malcomson

The “Communist Party of Peru — On the Shining Path of Jose Carlos Mariategui” was the product of intricate factional struggles in the 1960s and ’70s. Centered originally in the Universidad San Cristobal de Huamanga, in the Andean province of Ayacucho, Shining Path has committed acts of violence throughout Peru since beginning “armed struggle” in 1980.

The party governed some remote areas in 1980-82 until the armed forces intervened and brutally repressed the party’s activities. The sanguinary conflict continues: 1984 remains its bloodiest year.

The government’s Zona de Emergencia, which encompasses large sections of the Andes and has at times extended into the coca-growing jungles of the upper Huallaga River, is essentially under military government. Human rights do not exist in these areas. There are sizable remote regions where no government of any kind exists, and the campesinos are left to greet whichever armed group happens to pass through.

After he assumed office in 1985, Garcia attempted to discipline the military by firing several generals. Two massacres in Ayacucho in late 1985 suggested his discipline wasn’t having much effect. But for the year afterward both Sendero and the armed forces were relatively calm.

In the spring of 1986 Sendero began assassinating APRA officials, and the military retaliated with several murders. In October 1985, the massacre of several hundred Sendero prisoners near Lima, almost all of them unarmed, took the conflict to a new level.

Garcia’s efforts to reprimand the military were derisory. Sendero stepped up its assassinations, concentrating on Lima and the provincial capital of Huancayo. It also attempted, with little apparent success, to infiltrate trade unions. Lima has been under a provisional state of emergency for most of Garcia’s tenure, and during the small hours of the morning, after curfew, the military’s tanks are free to do as they like.

The electoral left takes great pains to distance itself from Sendero. Nevertheless, the alternative of armed struggle will probably gain plausibility as the polarization of Peruvian politics becomes more acute.

Peru’s main far-left newspaper, El Diario, has moved into virtually open support of the insurgents, and Sendero’s strength at Lima’s most important university, San Marcos, is formidable. San Marcos was invaded by troops in February.

Although Shining Path articulates no explicit economic plan, in the early “liberated zones” it enforced an authoritarian subsistence regime, in some areas forbidding all markets, all inter-regional trade, hired labor, and the use of machinery. These were considered phenomena of incipient capitalism.

All non-party organizations were forbidden. Sendero’s internal discipline is extremely rigorous, and when it has gained power in rural areas it has dealt with its opposition in a manner very reminiscent of the armed forces.

Within the Peruvian political imagination, Sendero represents less a coherent alternative than a sort of analogue to military rule — the other side of a debased coin. One often finds Peruvians reflecting that ultimately their choice will be between the military and Sendero. This is fatalism, not optimism.

Though information on current internal debates in Sendero is difficult to find, the party is apparently formulating a strategy for increased action within Lima, deviating from its traditional Maoist line of sur rounding the cities from the countryside. The urban assassinations are part of this shift in strategy.

See the Shining Path chapter in Michael Reid’s excellent Paths to Poverty (London: Latin American Bureau, 1985). The best treatment in Spanish is Carlos Ivan Desregori’s working papers Sendero Luminoso, v. 1-“Los Hondos y Mortales Desencuentros.” v. 2-“Lucha Armada y Utopia Autoritaria” (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1985, 1986); see also Rogger Mercado, El APRA, El PCP, y Sendero Luminoso (Lima: Ediciones Latinoamericanas: 1985), which reproduces some useful documents.

Quehacer, a Lima monthly, gives the most even-handed and astute treatment of Sendero within the Peruvian press. The London-based periodical, A World to Win regularly translates Sendero literature. Support groups exist in California and New York.

November-December 1987, ATC 11