Against the Current, No. 10, September/October 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Editorial: Korea Workers Take the Lead

— The Editors -

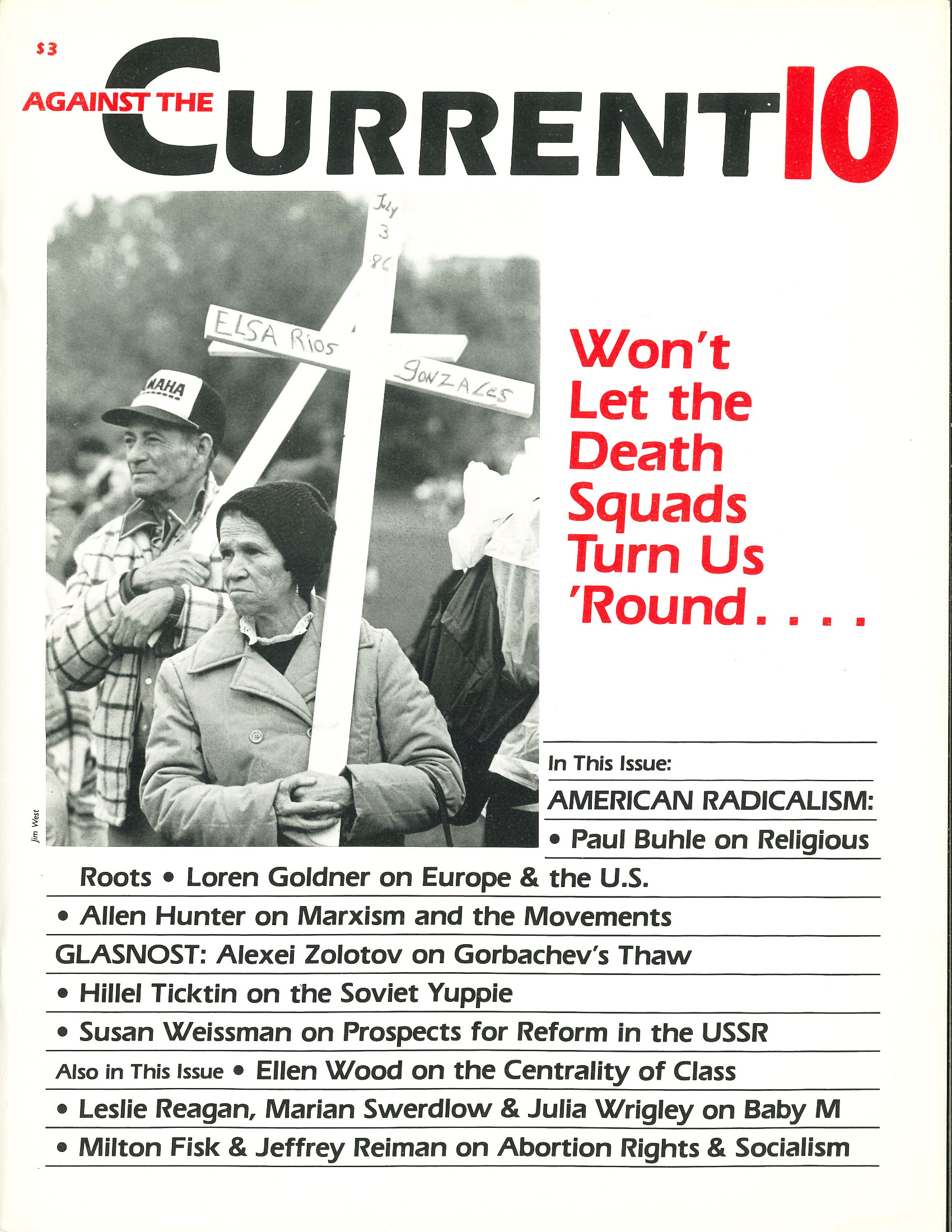

Death Squad Activity in Los Angeles

— Susan Wyler -

A Strategy for Irish Solidarity

— Bob Nowlan -

Why Class Struggle Is Central

— Ellen Meiksins Wood -

Random Shots: More Mines for Ronnie

— R.F. Kampfer - American Radicalism

-

Reflections on American Radicalism, Past & Future

— Paul Buhle -

Afro-Anabaptist-Indian Fusion

— Loren Goldner -

A Response to Paul Buhle: Limits of Religious Rebellion

— Allen Hunter - Abortion Rights & Socialism

-

A Group Liberationist Approach

— Milton Fisk -

Why Socialists Should Support Individual Natural Rights

— Jeffrey Reiman -

A Rejoinder: The Fallacies of Liberal Rights

— Milton Fisk - Looking at Glasnost

-

Gorbachev's Glasnost: Thaw II

— Aleksei K. Zolotov -

The Soviet Yuppie Takes Power

— Hillel Ticktin -

Who Benefits from Reforms?

— Susan Weissman -

Response to Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Justin Schwartz -

Reply to Question on Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Michael Löwy -

Whose Baby Is It Anyway?

— Julia Wrigley -

Surrogacy Is a Bad Bargain

— Leslie J. Reagan - Review

-

Wuthering Heights Revisited

— Michael Sprinker

Michael Sprinker

Emily Bronte

by James H. Kavanagh

Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell, 1985,

120 pages plus introduction, $8.95 paperback.

JAMES K. KAVANAGH’s Emily Bronte is part of the new series from Basil Blackwell edited by Terry Eagleton entitled “Rereading Literature.” Modelled on the highly successful and critically useful “New Accounts” published by Methuen, this series already features Laura Brown’s study of Alexander Pope, Steven Connor’s work on Dickens, and Eagleton’s own iconoclastic account of Shakespeare.

In the words of the series description, these books aim “to show how the insights of Marxism, feminism and deconstruction open up exciting new ways of reading the major work of the most commonly studied writers.”

In large measure, this focus reflects the ongoing critical project of Eagleton himself, aimed at remapping the theoretical and historical landscape of English literary study according to broadly materialist coordinates.

Kavanagh himself is entirely lucid about the means for achieving a revolutionary critical practice in literary study. He writes in the Preface to Emily Bronte: “a necessary part of the critical project in which this monograph participates is the development of a style, as different from the ‘plain’ style of criticism, perhaps, as is modernist from ‘realist’ prose, a dense and resonant style that continually foregrounds the difference between text and criticism which makes the latter possible” (p. xv).

What, then, are the instruments for the production of knowledge which Kavanagh brings to bear upon Emily Bronte’s novel? First and foremost, of course, are the principles of historical materialism, in particular its indispensable cornerstone, the concept of class.

Emily Bronte’s classic novel, Wuthering Heights, has been a fertile ground for previous Marxist criticism. Kavanagh shows how the novel does not simply or unambiguously symbolically portray the rebellion of the working class represented by, Heathcliff (as at least one Marxist critic would have it).

Rather, the novel presents the ideological struggle between the owning and the producing classes that was undoubtedly at the heart of Emily Bronte’s own life experience in early nineteenth-century York shire. This is part of a complex ideological fantasy of socio-sexual conflict cutting across any simple, direct identifications between a single character and the putative values of an entire class.

Heathcliff does, in various ways, occupy the position of the working class, but he does so ambiguously and for rea sons that are to do with determinations which are neither immediately nor solely class specific.

Psychoanalysis as Critical Tool

For Kavanagh, Wuthering Heights produces a textual ideology in the precise Althusserian sense of the term, that is, a “‘lived’ relation to the real” (Althusser) by means of which “the real and the imaginary constantly overdetermine each other, and through which the subject construes the social real in terms of his or her desire.” (p. 13)

One of the key ways in which the class “identity” of the novel’s characters becomes fissured is through its exfoliation of their Oedipal relations inside a family structure that is at once universal (not specific to any period or culture) and socially inflected (by the particular material determinations of a rural society touched by growing interclass strife and concerned to protect its principles of patrimony). The second of Kavanagh’s intellectual tools, then, is psychoanalysis.

Given the productivity in studies of Victorian literature among feminist critics, it would have been difficult for Kavanagh to ignore their intervention into the field of interpretation surrounding Wuthering Heights. The deflection of Kavanagh’s text by feminism is persistent and productive.

Playing off the orthodox anti-patriarchal theme pursued by two such feminists, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, he disrupts their tale of Emily Bronte’s despairing critique of phallocentrism — Cathy becomes the victim, in their view, of the phallocratic Heathcliff; correlatively, Emily Bronte was the doomed laughter of an overwhelmingly powerful poetic father, John Milton — by inserting at strategic points the quite different psychoanalytic feminism of Jane Gallop.

Appropriating Gallop’s discussion of the ”phallo-eccentric” and the “phallic mother,” Kavanagh identifies the novel’s central narrative tension in the conflicting socio-sexual projects of Heathcliff and Nelly Dean. Both represent the working classes, but each pursues distinct and opposed goals, even at those moments when they seem to have entered into an uneasy alliance.

Kavanagh’s interpretive skill is illustrated by his discussion of Penistone Craggs, which attentive readers of Wuthering Heights will recall as an important place in the novel’s symbolic topography. Kavanagh cleverly shows how this locale’s name condenses both the sexual and the social determinations of the text, concealing beneath the blatant sexual signifier of the first five letters significant associations with the economic foundations of life in West Yorkshire:

“Penistone” is the name of a small town in the West Riding, a centre for the production of a coarse, cheap cloth, of the same name. It derives from “penny,” and “penny-stone,” probably meaning “a penny a stone,” with “stone” signifying the British measure of weight equal to fourteen pounds. “Penny,” to complete the circle, derives from the Latin “pannus,” meaning “cloth (used as a medium of exchange).” (p. 91)

This bit of exegetical tenacity intervenes in a lengthy discussion of the family as primary site of social production under capitalism. Kavanagh’s insight into the ideological fantasy of Wuthering Heights focuses on the conflicting demands that capitalism makes upon the individuals it turns into subjects: you must be at once a worker and an instrument of capital, both a stable, reliable social agent and a free, unfettered element in the productive process.

The point where this set of contradictory commands meets is the capitalist family, the site of stable social reproduction as well as the scene of irreducible psychosocial rivalry. Wuthering Heights projects a solution to the crisis wrought by the imposition of capitalist social relations in the ostensible harmony of the newly instituted order at Thrushcross Grange at novel’s end-the utopian marriage of Hareton Earnshaw to Catherine Linton presided over by Nelly Dean, whom Kavanagh terms the “phallic mother as capitalism’s paradigmatic domestic labourer.”

This final disposition illustrates the text’s ultimate lesson: “that neither Capital nor the Father has actually to be — and in fact would rather not be — present in the family for this institution to function quite nicely on their behalf” (p. 95). The undoubted merit of James Kavanagh’s text is to have produced this knowledge, not only about Wuthering Heights itself, but about the family as an ideological apparatus under capitalism.

September-October 1987, ATC 10